Magic Island site at Southwest Freeway and Greenbriar Street. All photographs Paul Hester.

Paul Hester’s retrospective Doing Time in Houston at Architecture Center Houston---culled from his extensive archive documenting Houston’s architecture through all its transitions over the past 45 years--invites the viewer to contemplate all that has ever stood on this viscid alluvium we call home. Row houses razed to make room for rows of gated townhomes; first ring suburbs mowed down to clear space for skyscrapers. Here, a saddlery turned ballet parking lot; there, a sea food market turned newspaper headquarters. Even the buildings left standing have been stripped and fused and cloaked in marble panels or kitschy Egyptian temples (see my "Ancient Curse of Freeway Frontage Excavated from Archives," Cite 81, Spring 2010).

And at the center of our Ephemeral City is Market Square, which Hester has been researching and documenting since at least the 1980s. Aside from the produce stands it was named for, Market Square has been home to the Republic of Texas capital and three Houston city halls--the last city hall located there was repurposed and used as a bus depot for twenty years--before its first iteration as a public park in 1976.

Combination of Cecil Thomson (1925) and Paul Hester (1990) photos

Hester's documentation of Market Square calls to mind a passage from Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities:

[T]he traveler is invited to visit the city and, at the same time, to examine some old post cards that show it as it used to be: the same identical square with a hen in the place of the bus station, a bandstand in the place of the overpass, two young ladies with white parasols in the place of the munitions factory. Beware of saying to [the inhabitants] that sometimes different cities follow one another on the same site and under the same name, born and dying without knowing one another, without communication among themselves.

Even as Market Square Park, that one block has been fully redesigned three times in the 35 intervening years, and Hester’s research and photography was a main feature of the second-most-recent design. Hens...bus stations...bandstands...young ladies with parasols...all have occupied/do occupy/will occupy Market Square.

“The Aleph,” a short story by Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, opens with the narrator lamenting the appearance of a new billboard on the day his beloved dies. “[T]he fact deeply grieved me,” he says, “for I realized that the vast unceasing universe was already growing away from her, and that this change was but the first in an infinite series.”

This nameless narrator befriends his beloved’s cousin, a third-rate poet who, by way of the Aleph he discovers in his basement in Buenos Aires, “proposed to versify the entire planet.” He ingratiates himself to this cousin and finally wins an invitation to behold this Aleph for himself. “[A]n Aleph,” he tells the reader, “is one of the points in space that contains all points...the place where, without admixture or confusion, all the places of the world, seen from every angle, coexist.” There he finds himself at a loss for words, for “how can one transmit to others the infinite Aleph, which my timorous memory can scarcely contain?...[T]he central problem--the enumeration, even partial enumeration, of infinity--is irresolvable...What my eyes saw was simultaneous; what I shall write is successive, because language is successive.”

The Aleph, thus, becomes a fitting metaphor for this collection of photographs, this retrospective, this looking back which spans 45 years yet may conceivably be viewed within five minutes. The 68 photos are grouped together by decade, but the cumulative effect of the whole exhibition subverts the very notion that such temporal groupings are of any account. Change is the only constant: motion, captured, and fixed on light-sensitive paper for decades.

Nina Cullinan House, 1980

A forklift carries a palm tree across West Gray near the River Oaks Theater—frozen motion evidenced by the pitch between the roots and canopy.

A three-legged desk sits forever atilt in a threadbare concrete bunker.

The true mass of an airplane becomes evident only when it’s pinned beside evanescent clouds in a washed-out sky above a townhome development under construction where a man stands atop a five-story scaffold that casts the deepest shadows. He is painting the siding. There is a pile of dirt, and the rebar that will support the future brick wall stands exposed.

Looking down on a vacant parking garage and out toward the Williams (nee Transco) Tower, fluorescent light tubes—reflected in the invisible window of what could only be the most nondescript office—cut across the all but vacant horizon.

Looking south down Post Oak Avenue from another office building we see a courtyard reflected in an obsidian skyscraper. Traffic islands take on the appearance of amoebas from this perspective.

You might say that each of these photographs is a timeless document with the “eternal present” as its true subject (except, of course, those showing indoor ashtrays and dated clothing styles), but it is the photographs of construction and demolition sites which retain the most currency.

Ghost of Shamrock Hotel

The high contrast night-time shot of a demolition downtown in the 1980s section looks very much like it could be a depiction of the YMCA demolition just a few short weeks ago. Nearby, the gray rendering of the excavation of the Weslayan Tower foundation (also from the 1980s), if framed just right, could be a shot of the excavation currently underway along Brays Bayou near SH 288.

The multiplicity and simultaneity implied by the juxtaposition of these fleeting moments becomes most apparent in the final grouping where, under the banner “Wrinkles in Time,” Hester has layered images in photo mash-ups of singular points in space taken from different moments in time. This digital layering is a continuation of such juxtapositions as those on his Market Square tiles dating back to 1990, two of which are displayed here.

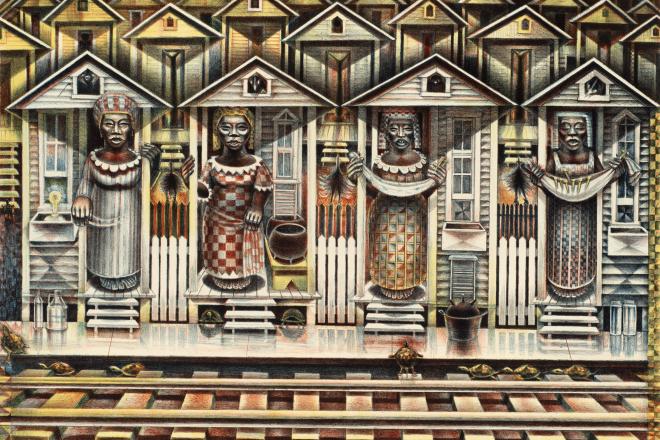

He shows us a black and white ghost of the Shamrock Hotel towering over the parking lots which replaced it, rendered in color. We see the before and after photographs of the “Indeterminate Façade” Best Products Showroom, which was altered in 2003 to lop off the “crumbling” features that once made it singular. We see the Wilson Furniture showroom beneath Magic Island, an art-deco Walgreen’s on Main at Elgin with the light rail going past, and the original location of the Menil Collection beside the Rice Media Center. We see St. Agnes Academy on Fannin at Isabella where a monstrous three-story apartment block now sits.

For some viewers, the bulk of these photographs may engender a sense of loss—the loss of bygone aesthetic styles and respect for history in favor of cheap, mass-produced, prefabricated dreck. For those viewers, one photograph in particular might provide a (fleeting) sense of just desserts: it shows a townhome, abandoned before its construction was even complete, wrapped in tattered Tyvek. The only part of this shell-of-a-townhome that retains its integrity is the strip of glossy advertising photographs across its face which show what it was supposed to have looked like, and according to Hester, that never-built building, too, was torn down soon enough.

Individually, Hester’s photographs reveal that, in the words of poet A.R. Ammons, “we are rippers and // tearers and proceeders,” yet, taken cumulatively in this temporary, scaled-down version of a Houston Aleph, they capture “the stillness all the motions add up to.”

Stop in soon to catch a glimpse of Paul Hester’s Houston Aleph. It may indeed capture the eternal present, but after Friday, August 12 it, too, will be taken down from the walls of ArCH to make room for their next show.

*One final note: Viewers may recognize the interior shot of the Philip Johnson designed Republic Bank (now Bank of America) lobby. That vast emptiness appears in the recent Terrence Mallick film Tree of Life—yet another meditation on the singularity of all existence.