August 3, 1995, was the day that changed hip-hop forever. Onstage that night at the Source Awards, in the midst of tension between East Coast and West Coast rap acts, André 3000 and Big Boi of the Atlanta rap duo Outkast was awarded “New Artist of the Year, Group.” Claiming their award, André 3000 famously declared, “The South got something to say.” A stamp of approval from the most authoritative hip-hop publication in the world was a rite of passage, a cementing into history. Outkast’s triumphant win signified a necessary shift and made it clear that artists from the South would no longer be dismissed, underestimated, silenced, or ignored. This moment christened the future of Black Southern creative expression.

Galvanized by this pivotal moment, The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse unearths a century of intersections between the aesthetic and musical traditions of the Black South. The exhibition, conceived by Houston-born curator and scholar Valerie Cassel Oliver and originated at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, opened at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston in November 2021. On view through February 6, the groundbreaking exhibition features over 130 artworks by a multigenerational group of artists and is divided into three major themes: landscape, spirituality, and the Black body. After closing in Houston, the show will travel to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Denver.

The Dirty South opens with an exploration of the Southern landscape. I looked over Jordan and what did I see; a band of angels coming after me (2017), a sculpture by Nathaniel Donnett, grounds viewers in the space. Taking its title from the slave hymn “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” the work replicates the exterior of a shotgun house, a distinctly Southern architectural form that emerged after the Civil War and defined some of Houston’s predominantly Black neighborhoods, including the historic Third and Fourth Wards. A rusted machete is suspended from the window in an ode to Black agricultural workers, while an electric blue light seeps through the wooden panels. It’s an expert placement that underscores the specificity and significance of Houston’s place in the exhibit. Echoes of shotgun architecture appear in a painting by the prolific artist and educator John Biggers and a photograph by Earlie Hudnall, Jr., which captures the stark contrast between the dilapidated houses in Fourth Ward and the towering Houston skyline in 1983, an eerie depiction of past and future.

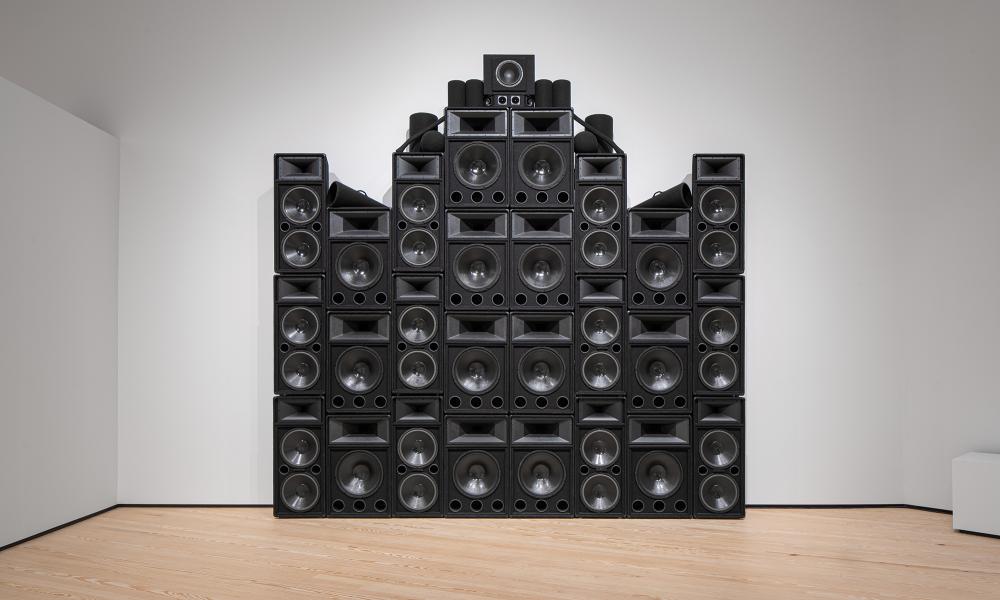

Another triad of artists explores the spirit of Black music through immersive installations. Sounds permeate the galleries at varying volumes and registers. Pulsating through the main gallery is the soundtrack to Nadine Robinson’s sonic sculpture Coronation Theme: Organon (2008). Made of thirty speakers whose stacked form mirrors both a large pipe organ and the facade of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, the sculpture emits a soundtrack of prayers, songs, and the murmurs of Civil Rights-era protest chants. Robinson fuses genre and geography with a work that takes inspiration from Jamaican sound system culture and recalls the prevalence of contemporary hip-hop. In keeping with sculptural tributes to Black music, Rodney McMillian pays homage to the Dockery Plantation in Mississippi, the birthplace of the blues. In the hand-sewn vinyl work From Asterisks in Dockery (Blues for Smoke) (2012), McMillian mimics the design of a one-room chapel, another architectural form common in the rural South. The chapel is outfitted with a pulpit, pews, and a makeshift cross, while its blood-red vinyl evokes a sacred space of communion. The evolution of Black music continues in Houston-born pianist Jason Moran’s shrine to Slugs’ Saloon, a now-defunct hub in New York City’s East Village that was a critical site for experimental and free-form jazz musicians, including Texas musicians Ornette Coleman and Ronald Shannon Jackson.

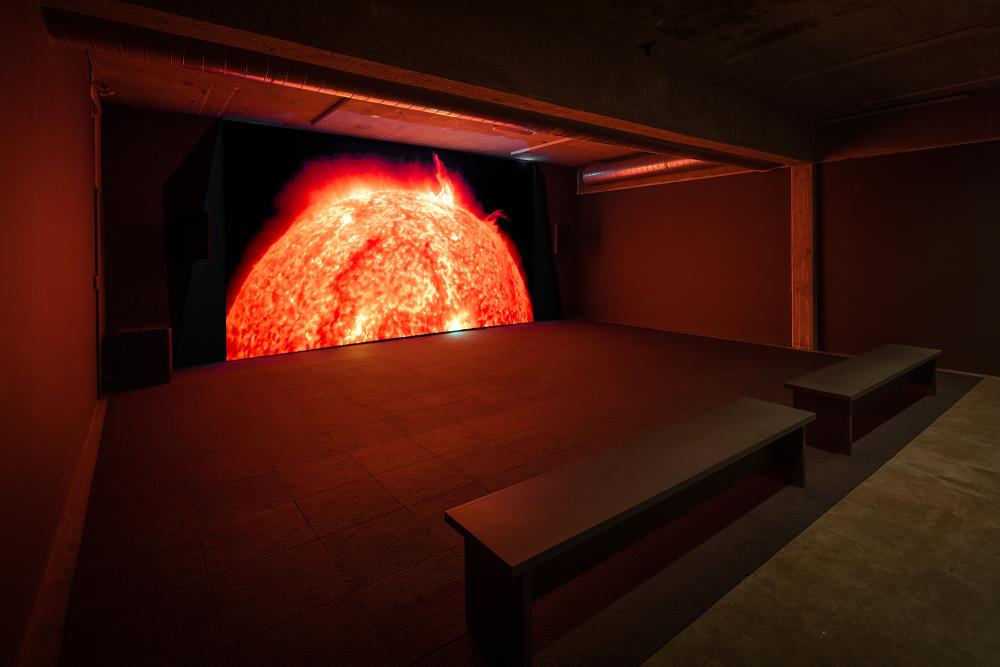

The visual and sonic climax of The Dirty South’s Houston presentation live in two works showcased on the museum’s lower level: a mural-like painting of DJ Screw (1971–2000) by El Franco Lee, II, and Arthur Jafa’s seminal video essay Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016). In DJ Screw in Heaven 2 (2016), Lee depicts Screw, the architect of the South’s most distinct and notorious style of contemporary hip-hop, in the center of the composition surrounded by members of the Screwed Up Click. His hands are placed on two turntables that rest above sweeping scenes of mourning. Loaded with detail and symbolism, this painting commemorates the life, transcendence, and legacy of a cherished music pioneer. In the final work of the exhibition, Jafa, born and bred in the Mississippi Delta, captures the beauty and monstrosity of the Black American experience. A seven-minute sequence of images pulsates to the cadence of Kanye West’s gospel track “Ultralight Beam” and bridges centuries of excruciating pain with immense joy and perseverance. Both Lee and Jafa capture catharsis and ecstasy.

The Dirty South traverses key sites in Black history—the plantation, the church, the saloon, and the streets of the nation’s cities—to great acclaim. The show was recognized by critics Holland Cotter and Roberta Smith in The New York Times as one of the best art exhibitions of 2021. Beyond its presentation in galleries, this collection of artworks is captured in an accompanying catalog, published by Duke University Press.

From gospel to blues, jazz, and hip-hop, Black music is arguably the biggest American cultural export of the 20th century. The links between American history, the South, and Black cultural expression are inextricable. Deep sonic and visual practices were set in motion by the violence of the Atlantic slave trade. Since then, a series of movements and displacements have shaped the experience of Black people: the era of Reconstruction, the Great Migration, Civil Rights, the crack epidemic, and mass incarceration. Growing up and out from these historic roots, hip-hop inspired a generation of artists from the South to make their work with a sense of pride in place. These artists are proud of their homes, cities, and the South, this complex-but-beautiful region within our wretched nation. At its core, The Dirty South celebrates the underrecognized legacy of ingenuity and resilience that lives here. The South is the foundation, genesis, and origin for so much. It speaks to us, and we will continue to talk back.

A version of this review is forthcoming in Cite 103.

Amarie Gipson is a Houston-born writer, critic, and aspiring art librarian. Gipson authors The Art of Return, a monthly newsletter on art, Southern culture, and Black womanhood.