At the end of 2021, a newly renovated Bagby Street in downtown Houston was revealed through the Winter Wanderland, an event organized by the Downtown Management District. Lighted canopies were placed over the new cycle track and holiday ornamentations decorated the enhanced sidewalks. Funded by the Downtown Redevelopment Authority (TIRZ 3) and under the consultation of seventeen stakeholders, the $29 million Bagby Street Improvement Project (BSIP) is part of City of Houston’s Complete Streets initiative to transform streets into walkable and bike-friendly spaces. Traffic Engineers, Inc. conducted preliminary engineering for Bagby Street, while the landscape design firm SWA and the civil engineering firm Jones Carter completed the street design work.

“Bagby Street” refers to two rights-of-way in Houston, one in Downtown addressed by BSIP and another in Midtown, which dead-ends in Montrose. These two streets have always been separated by the Seneschal Addition, a Reconstruction-era development at the easternmost edge of Freedmen’s Town.

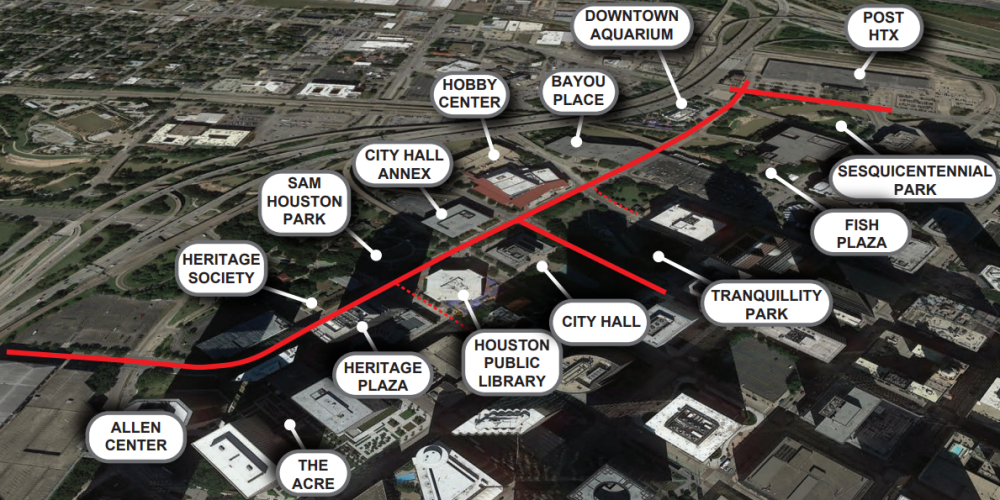

Bagby Street in Downtown is a destination corridor of commercial office towers, public buildings, and parks: The Aquarium overlooks Bagby Street between Prairie Street and Texas Avenue, just before the throughfare runs through Bayou Place, and continues past the Hobby Center for the Performing Arts, Lyndon Baines Johnson Memorial, Tranquility Park, City Hall and City Hall Annex, Sam Houston Heritage Park and Harris County Historical Society, Jesse Jones branch of the Houston Public Library, Texaco Heritage Plaza, and C. Baldwin Hotel. The street terminates at Franklin Steet to the north and runs south for ten blocks (about a half mile) until it veers true west and turns into West Dallas Street.

In Downtown Management District’s final report, the BSIP characterizes Bagby Street as “The Gateway into Downtown,” but also as “A Street of Parks,” alluding to the six parks, three plazas, and a promenade that lie along the corridor. Despite it being an arterial road serving high volumes of traffic, most blocks on Bagby contain some public space.

History: From Dead End to Unified Arterial

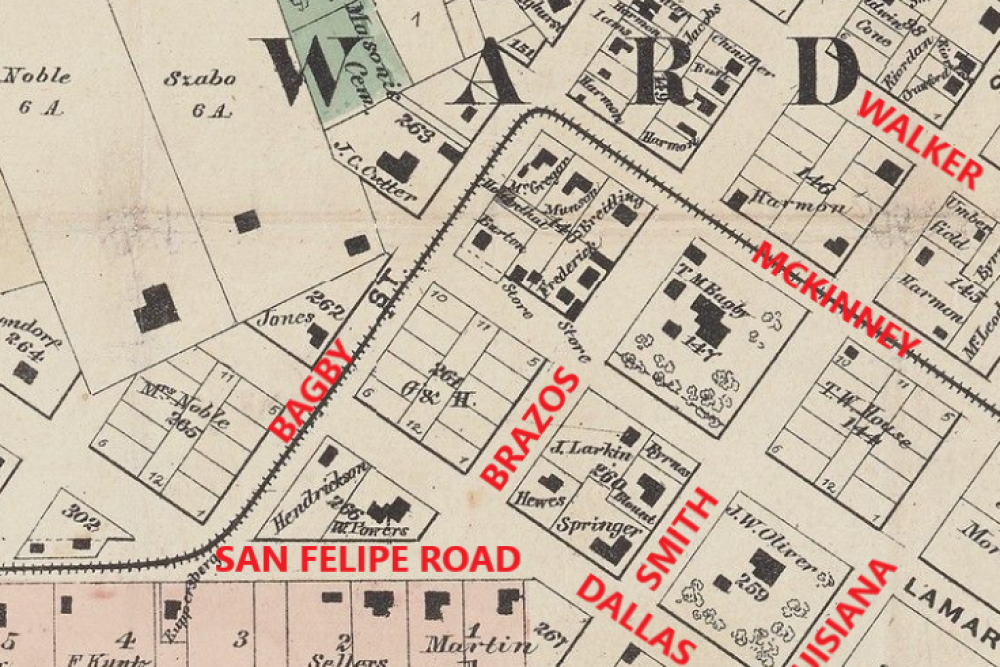

The street known as Bagby Street today first appeared on an extent map dated January 19, 1837.[i] The street, named after Thomas Bagby (1814–68), was labelled as “Bagby Street” for the first time on the 1873 Birdseye Map of Houston. Bagby was a successful merchant who arrived in Houston in 1837 and eventually served as an alderman for the Fourth Ward. Although information on the building footprints and the residents from pre-Reconstruction era is limited (and skewed toward wealthy White property owners), the 1869 Wood Map shows Bagby’s homestead on Block 147, the current location of the Julia Ideson Building located one block east of Bagby Street. Other than the records of wealthy merchants like Bagby, little is known of the residents from that time period. [ii]

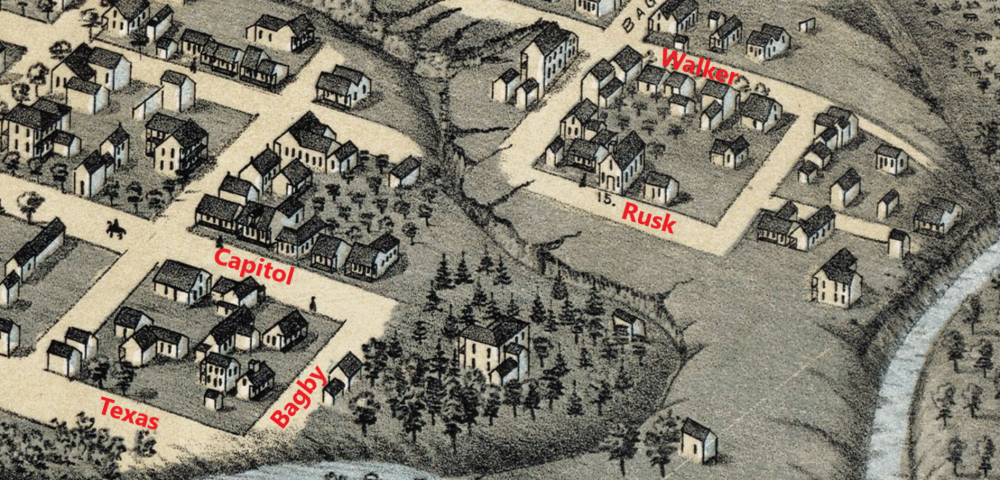

Maps dating to 1869, 1873, and 1896 show that Bagby Street touched various neighborhoods, which were isolated by Buffalo Bayou and the two deep gullies feeding into it. On the northern end, the street terminated at the ridge of the ravine overlooking Buffalo Bayou. As captured in both the 1873 Bird’s Eye Map of Houston and the 1896 Sanborn Map, a large and deep gully ran between Walker and Rusk, and Bagby Street ended before reaching Capitol Street. The gullies and ravines made many of the blocks along Bagby Street only partially accessible.

Although creeks, streams, bayous, and rivers are dynamic features and change over time, it’s useful to note the differences in how the neighborhood is represented among maps. Unlike the maps referenced in this piece that show consistency in the geographic features, maps like the 1837 Borden Map and the 1891 Map of Houston reduced the presence of gullies and ravines, depicting the lots in the neighborhood to be more developable. According to the Birdseye Map of 1873, one block of Bagby was isolated between Texas Avenue and Capitol Street by Buffalo Bayou and a gully. The gully also slices the two blocks between Rusk Street and Walker Street, and continues past the implied path of Bagby on its way through sparsely developed land to the bayou. While the neighborhood demographics of Fourth Ward are not well-captured until the end of 19th century, the “colored church” (as listed in the map’s key) drawn on the 1873 Bird’s Eye Map with the label "15", suggests that there was already a Black neighborhood coalescing around the block west of Bagby between Rusk and Walker, where the Hobby Center and Tranquility Park stand today. The records from 1880 and 1900 census confirm that there was a notable Black population (among other populations), and that the area was home to many Black businesses.

In the 1890s, the City of Houston established sewerage districts for street improvements. Although the first network of sewers was completed by 1902,[iii] the city’s sewerage system in the early twentieth century was woefully inadequate for handling heavy rainfall.[iv] Yet as the Sanborn Map of 1907 shows, much of the gully between Rusk and Walker had been filled by that time, leaving us to imagine that the Bagby residents were periodically besieged by flooding without adequate underground capacity to address the runoff. The neighborhood was hit especially hard by the Flood of December 1929 and the Flood of 1935, two apocalyptic events in which the water rose above the south banks of Buffalo Bayou.

During the early twentieth century, Bagby Street coalesced into a coherent corridor, over time transforming into a civic center for Houston. Houston’s first comprehensive city plan, published in 1913 by landscape architect Arthur Comey, identified the west side of Downtown as the city’s new civic center.[v] The traffic on Bagby Street increased after the Preston Avenue Bridge was rebuilt with concrete in 1914, and another concrete bridge was built on Capitol Avenue in 1915.[vi] In 1925, the City Council approved the plan for Houston’s civic center designed by the engineering and landscaping firm Hare and Hare, which was bounded by Texas and Lamar Avenues and by Bagby and Smith Streets.[vii] Buffalo Bayou was expanded and engineered, uneven blocks were levelled, and the gullies between Rusk and Walker, Walker and McKinney were both filled.

Over the next few decades, the city claimed more land, demolished more houses, and constructed new public buildings including Sam Houston Hall (1928, demolished), Houston City Hall (1939), Music Hall (1938), Sam Houston Coliseum (1937), Houston Fire Alarm Building (1939, demolished), Albert Thomas Convention Center (1960, now “Bayou Place”), Jesse Jones Branch of Houston Public Library (1975), Tranquility Park (1979), and Sesquicentennial Park (1986).[viii] Adjacent commercial buildings include two parking garages, C. Baldwin Hotel, and Texaco Heritage Plaza. With these large buildings constructed on leveled surfaces, a system of underground pipes was installed to direct the runoff towards Buffalo Bayou in place of the gullies.

Bagby Street eventually became an arterial road known as “The Gateway into Downtown,” serving high volumes of high-speed traffic going to and from expressways including I-10, I-45, Washington Avenue, Memorial Drive, Allen Parkway, and West Dallas Street. Despite it being home to many of Houston's civic institutions and offering several green public spaces, the street was not very accessible to pedestrians and cyclists.

Review: Bagby Street Improvement Plan

The BSIP began in 2017 to address the heavy motor traffic of Bagby Street, while enhancing its public spaces as part of Houston Complete Streets Transportation Plan to, “provide safe, accessible and convenient use by motorists, public transit riders, pedestrians, people of all abilities and bicyclists.” BSIP’s objective was to transform Bagby into a “signature street” and a “premier multimodal corridor for all users” by celebrating it as “Street of Parks,” while retaining its role as an arterial road for downtown Houston. The plan proposed a road diet that would calm the traffic through street beautification, and reallocation of the right-of-way from vehicular traffic to cyclists and pedestrians. It does not assume a reduction in motorized traffic; rather, it assumes that the current traffic levels and average speeds will remain constant despite the reduction in the general traffic lanes. It’s a modest plan for an urban street, while being a radical plan compared to the wide streets engineered for high-speed traffic that run through most of Downtown. The project also involved the inspection and refurbishing of the underground infrastructure, since the street was due to be torn up and rehabilitated.

The biggest change in Bagby Street is the reconfiguration of the right-of-way. The redesigned street added a center island on one block, and for several blocks redistributed one of the general traffic lanes to wider sidewalks and a raised two-way bike lane. This treatment of Bagby is an important corrective to the high-speed and impatient driving in this part of Downtown. The City added these features without making the right-of-way any wider or any narrower. There are still some characteristics of Bagby and intersecting right-of-ways which read as high-speed roads—including large setbacks, and some straight, flat segments—and drivers are still reluctant to slow down. However, the Bagby Complete Streets Project demonstrates that the City of Houston is committed to improving its civic space.

Bagby Street is now greatly improved for active modes of transportation. Those arriving and departing the corridor by bus, bike, wheelchair, or on foot have access to spacious and attractive cycle tracks and wide sidewalks that are clad in high-quality polychrome paving stones. The two-way cycle track runs along the east side of the street and is grade-separated for most of the length, while well-defined border pavements clearly distinguish it from the sidewalk. New landscaping and integrated street lighting add to comfort, day and night. The reduction in general traffic lanes may have a calming effect on the traffic, but the greatest safety benefit comes from the cycle track. Riding a bicycle on the sidewalk is illegal in Downtown, which means it is only legal to ride in cycle tracks or general traffic lanes. With this new cycle track, Downtown’s visitors can easily travel north and south along Bagby Street, and access a number of public facilities including parks, plazas, libraries, museums, performance venues, and government buildings. The protected cycle track on Lamar Street facilitates bicycle access to George R. Brown Convention Center and East Downtown. The enhanced walking environment also leverages the buses which serve this corridor.

Focusing on the length of the street that is fronted by City Hall on the east side and City Hall Annex on the west, the two civic spaces extend to the public street through the widened sidewalks. On the east side, the twelve-feet wide cycle track runs between the sidewalk and the carriageway (the area inside the curbs). The track includes a one-foot border pavement on each side, creating clear markers between the cycle track and the sidewalk that measures twelve to fourteen feet in width. There is one feet of curb width and a five-foot allowance for utilities and landscaping that separate the cycle track from the road, creating a comfortable distance from the high-speed vehicles. On the west side, the sidewalk measures ten to twelve feet for most of the block’s length, except when it is interrupted by driveway zones that narrow the sidewalk to about eight feet. Like the east side of the street, the west side includes a one-foot-wide curb and a five-foot-wide utility and planting strip.

The BSIP enhances the corridor as an interconnected series of destinations through the infrastructural improvements. Among these destinations are major office towers, government buildings, entertainment venues, and open public spaces. The new cycle track and expanded sidewalk in Bagby is a great asset for downtown Houston. These are spacious and beautiful facilities, implemented without an expansion of the right-of-way.

Several questions arise about the corridor. Who will be the main users of these gorgeous sidewalks and the cycle track? How does the present land use influence how the street will be used? With drivers entering the Bagby corridor from highways and high-speed corridors and preparing to get away from downtown, will they respond to traffic-calming cues while crossing Bagby? Will there be future Complete Streets to complement the BSIP? It appears that Bagby is presently a commuter corridor with the automobile as the principal conveyance.

Bagby Street has transformed significantly from 1837 to today. From a minor disjointed street serving a few people who took advantage of cheap land at the fringes of Republican and antebellum Houston, these neighborhoods grew in population after Texas annexation and served elite merchants, their clerks, and tradesmen. In the twentieth century, it coalesced into a neighborhood with many Black residences and Black-owned businesses. In the early twentieth century, developers and municipal engineers flattened the topography, beginning to transform Bagby Street into a thoroughfare. Urban renewal swept away the housing from the corridor, engineers designed a network of modern bridges to facilitate Bagby’s vehicular traffic, and the land was redeveloped to serve government buildings, parks, and other public spaces. Today, the BSIP has transformed Bagby Street into a destination corridor that supports a broader range of street users.

This history has shifted from an idea that, “Houstonians planned around the bayou because the city did not have the resources to tame it,” to the “planned and engineered Bagby” that we know today. Although still heavily used by cars, the latest improvement delivers better access for cyclists and pedestrians. As a destination, Bagby Street is best experienced by active modes of transportation. Visitors will have an easy and comfortable means of enjoying public amenities, experience the relationship between Bagby Street and Buffalo Bayou, and contemplate the natural and human history of Houston.

Jon Boyd is an independent historical researcher. His current project is Houston Lodging: Residential Hotels, Boarding Houses, and Restaurants, 1837–1877. He also publishes the “What Are Streets For Newsletter,” which covers land use, transportation, and urban history.

Notes

[1] “Borden Map of Houston,” Houston Metropolitan Research Center, facsimile from its map collection.

[2] 1860, 1870 United States Census, Harris County, Texas, Houston, Fourth Ward.

[3] Barrie Scardino Bradley, Improbable Metropolis: Houston’s Architectural and Urban History (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2020), 79.

[4] Martin V. Melosi, Sanitary City: Urban Infrastructure in America from Colonial Times to the Present (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 238.

[5] Bradley, Improbable Metropolis, 117.

[6] Louis F. Aulbach, Buffalo Bayou: An Echo of Houston’s Wilderness Beginnings (Houston: Louis F. Aulbach, 2012), 231, 246.

[7] Bradley, Improbable Metropolis, 117–8.

[8] Bradley, Improbable Metropolis, 118, 121–2, 150, 232, 253–4; Aulbach, Buffalo Bayou, 230–1, 250–1; Steven Fenberg, Unprecedented Power: Jesse Jones, Capitalism, and the Common Good (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2011), 140–1.