The Racial Geography Project is a research collective that began in July 2020, in the midst of nationwide protests against the police brutality and the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and many others. As part of Rice University Task Force on Slavery, Segregation and Racial Injustice, which investigates and engages in discussions on the role of slavery in the University’s history as well as the ongoing debate about the Founder’s Memorial in the Academic Quad, the collective studies the material impacts of slavery and segregation that have been codified into our built environment—on Rice campus and in the larger web of economies that have supported the institution.

Led by Fabiola López-Durán, Associate Professor of Art and Architectural History, and Adrienne Rooney, Ph.D. Candidate in Art History, the collective of graduate and undergraduate activists and scholars research topics ranging from W.M. Rice’s relationship to plantation economy, to the forest in southwest Louisiana owned by Rice-Land Lumber Company as covered in Cite 103, to the experiences of the first Black students, faculty, and staff at Rice. The collective’s ongoing efforts connect and make visible the ways in which the exclusionary practices and policies of the past and the resistance are embedded in our built environment, the very space where we continue to learn and work today. López-Durán and Rooney spoke with Cite’s former Editor Jack Murphy earlier this year.

Jack Murphy: How did the Racial Geography Project (RGP) start?

Fabiola López-Durán (FLD): The Racial Geography Project (RGP) began in July 2020 as protestors filled the streets worldwide after the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd at the hands of the police. As a member of the Rice University Task Force on Slavery, Segregation and Racial Injustice whose work was already well underway, I began thinking about how to make visible the research that we were conducting as part of the Task Force’s charge.

In one of the Task Force meetings, Dr. James Sidbury, Professor of History, mentioned a “Racial Geography Tour” created in the early 2000s by Dr. Edmund T. Gordon, Associate Professor and founding chair of the African and African Diaspora Studies Department at the University of Texas at Austin. It started as a walking tour and ended as a digital one, offering a travelogue of the role played by ideas of race in the conceptualization and materialization of the campus’ layout, landscape, architecture, and landmarks.

This project was the spark of our own Racial Geography Project, and I invited Adrienne to co-direct a research collective with me. With the full support of the Task Force Co-chairs Dr. Alex Byrd and Dr. Caleb McDaniel as well as the Task Force’s Teaching and Research Working Group, we invited a group of students to join us. The research collective’s founding group was an interdisciplinary group of twenty-two graduate and undergraduate students, including those who participated in our Fall 2020 class Art and Activism: Creative Protest in the 20th Century Americas, and the Summer 2020 Anti-racism Reading Group that Adrienne organized for the Art History Department.

How does the RGP operate and what is its structure? Is it a class that students take or a group of scholars working together?

Adrienne Rooney (AR): The RGP is an independent research collective of scholars and activists from disciplines across the university. As a research collective, we seek to learn together from co-researching, co-writing, and crowd-sourcing knowledge. Our project is modeled on an idea of knowledge production and sharing that calls for a range of research, cultural backgrounds, life experiences, and perspectives. We believe that it is only through such form that we can work against hierarchical and exclusionary means of shaping the world through historical narrative.

The RGP is structured into five smaller groups of graduate and undergraduate researchers focused on a particular area. The collective meets a few times a semester—often joined by Dr. Byrd, Dr. McDaniel, and Dr. William Jones, a Postdoctoral Research Associate working with the Task Force—to discuss updates, findings, and plans.

What were the key motivations/ambitions for the group at its outset? How have they changed over time?

FLD: Catalyzed by waves of protests and necessary conversations about the racialized fabrics of cities and memorials, we envisioned a project that could offer a different map of the campus: one that seeks redress, one that tells stories of racial violence registered in our surroundings, and one that tells stories of organized and daily resistance by the students who would have been excluded by the University’s original whites-only charter.

The collective has so far investigated five areas of research. As it ages, we plan on expanding the research areas based on research leads and the interests of the members. There were about forty topics initially, many of which we hope to delve into as we work to reconfigure the metrics for accomplishment embedded in our geography.

Can you review some of the research topics and findings that the RGP’s members have worked on and are working on?

AR: We have time to mention only a small number of findings, but there are 120 others, some of which are summarized in a working document published on the Task Force website. The full expanse will become publicly available this year via an online diachronic map created in collaboration with Dr. Farès El-Dahdah, Professor of Art History.

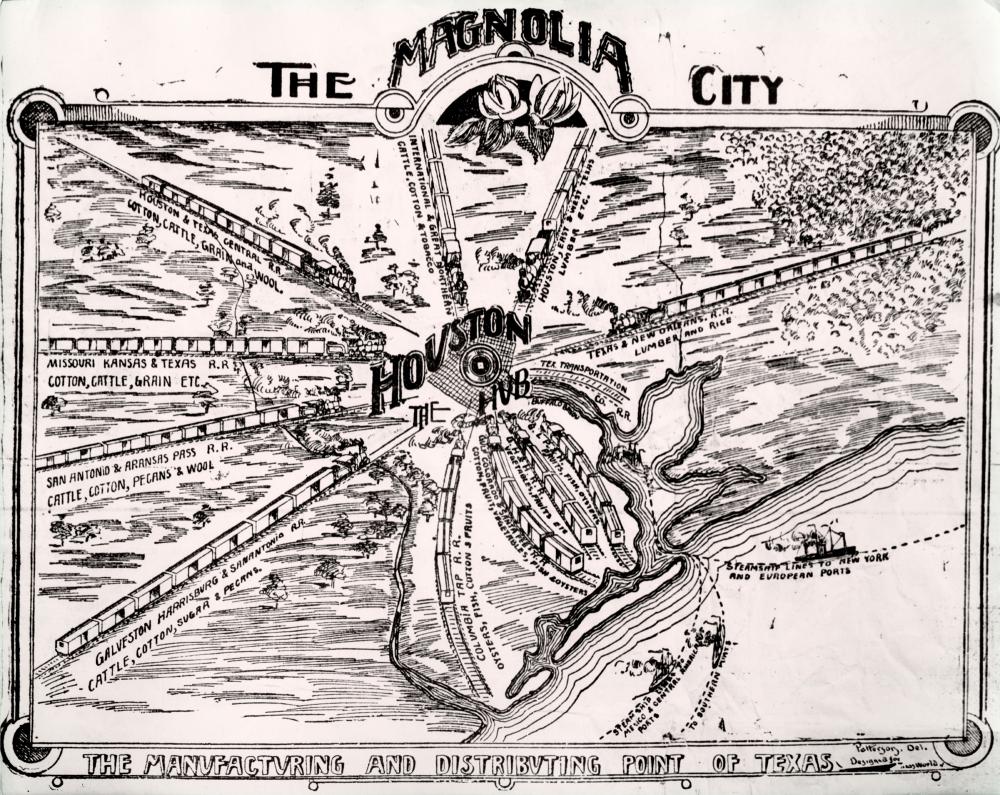

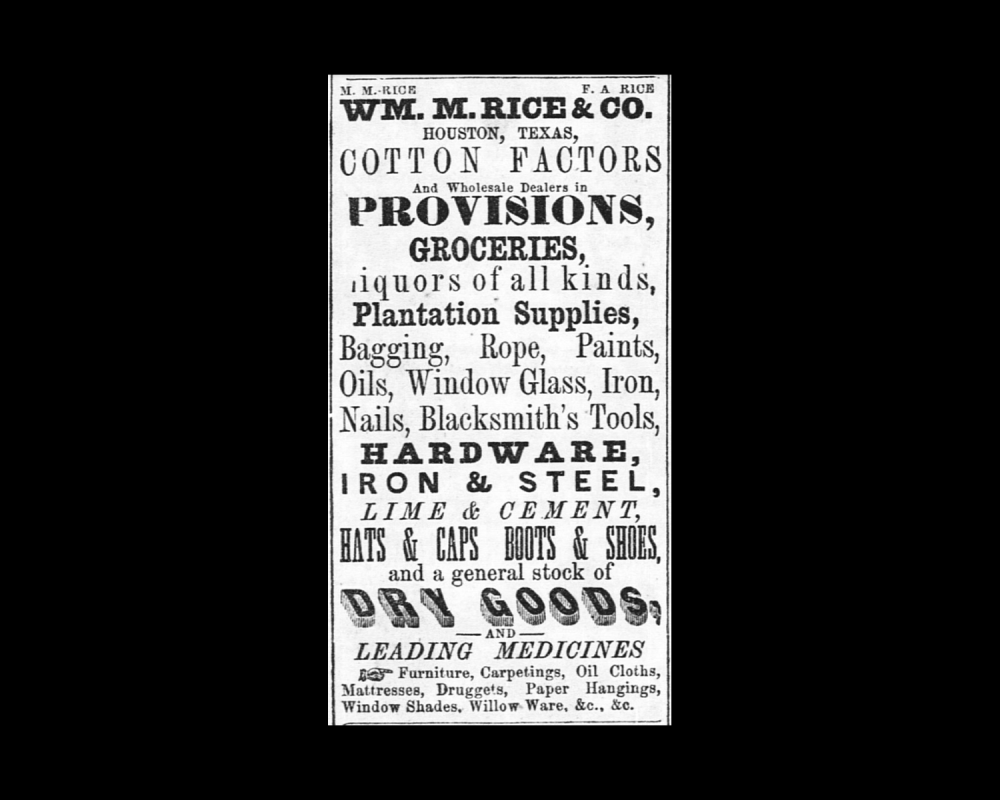

I have been working with Soha Rizvi and Chaney Hill, members of the William Marsh Rice and Slavery research group, to study the relationship of W. M. Rice to slavery and the plantation economy. The bottom line of all of our work is that Rice’s profits before Emancipation can’t be separated from either. Not only did his store sell “plantation supplies,” he set up and registered the Houston Cotton Compress Company, which, as Chaney explains in her RGP podcast episode, “aimed to expand Houston's role in the global cotton markets, linking southern plantations with other states and countries.” Rice worked to establish transportation networks to make transporting cotton—a central plantation crop reliant on enslaved labor—more efficient. During the Civil War, Rice avoided Union blockades by exporting cotton from the US South to Matamoros, Mexico. From there, cotton was channeled via Cuba and the Bahamas (at the time, colonies of Spain and Britain) to the northeastern US or abroad.

Moreover, Rice served as a creditor to the Confederacy and plantation owners, which at times meant that he treated enslaved adults, children, and unborn children, to put it bluntly but honestly, as financial assets. He also directly enslaved people and took part in the purchasing and selling of enslaved individuals, some of whom may have lived and forcibly worked in, among other locations, Rice’s downtown mansion. The mansion has been preserved at Sam Houston Park. I’m still trying to learn more about the locations where adults and children, enslaved by Rice, lived, took care of one another, loved, and made their culture—with the hope that they may someday serve as spaces to honor them.

A central part of the research group’s efforts has been to glean information on these enslaved individuals through deed books, financial documents, and fugitive slave ads, learning the names and very partial stories of individuals from whom Rice profited. For example, we learned about a seventeen-year-old woman named Ellen and her one-year-old child Louisa that Rice “gifted” “the half interest owned by him” to the young son of his long-time business partner Ebenezer Nichols [1]—sit with that. In addition to trying to learn what we can about the individuals that Rice treated as property, we’re also trying to emphasize, in our presentations to current Rice students, the extreme limitations and continued dehumanization of enslaved individuals, precisely through learning about people via such financial documents.

The Task Force’s June 2021 report on slavery, which includes the RGP’s work, makes clear that the University is indebted to the enslaved adults, children, and unborn children who W. M. Rice treated as property, as well as to the countless individuals whose forced labor directly or indirectly profited Rice. If we treat the founder as forming the school’s financial bedrock, they too are founders of Rice University, and they should be recognized and honored as such.

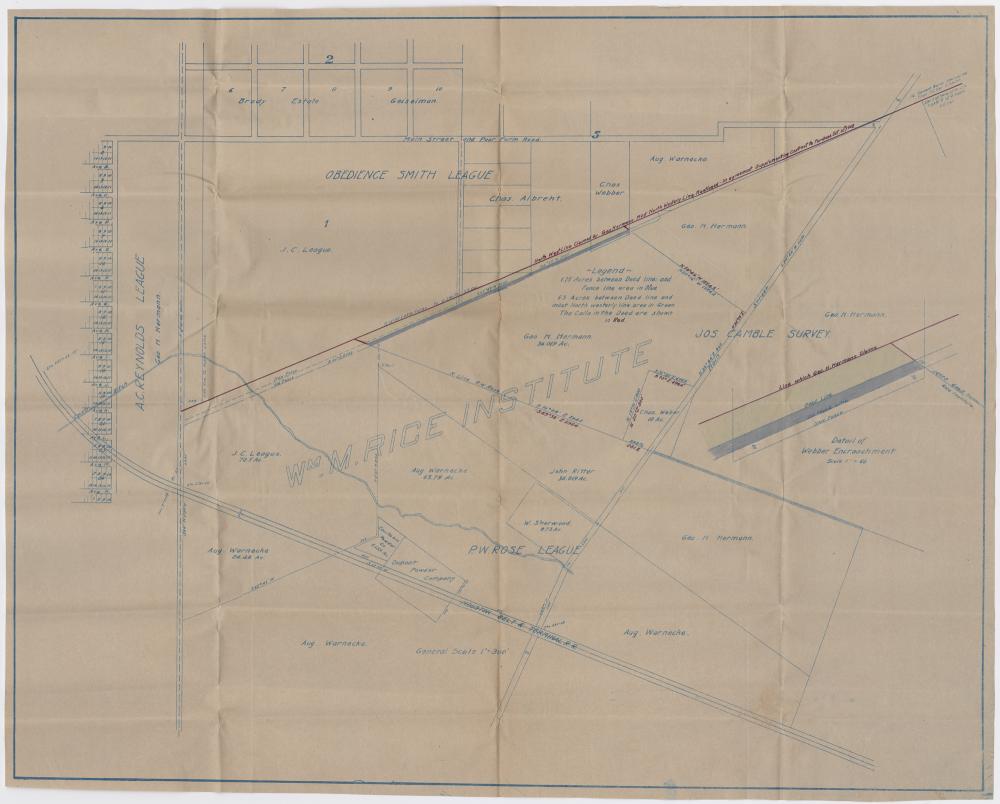

FLD: In addition to learning about those who have constructed Rice University’s campus and cared for its grounds, the Land, Architecture, and Labor research group investigates technologies of segregation and environmental racism implemented in the construction of the campus—from the initial settlement and the industries that funded its buildings, to the stories embedded in its architectural materials, designs, and ornaments. Located in the City of Houston, Rice campus occupies land that was seized from indigenous people. Key to this violent colonization process were racialized land grants that the Republic of Texas offered to encourage Anglo immigration. Giovanna Bassi Cendra’s research shows that Rice University and W. M. Rice were beneficiaries of this unfair and cruel system of land dispossession and occupation. As her RGP podcast episode explores, Rice received a certificate for 320 acres in the City of Houston in 1839, which helped him to begin building his fortune; the 185-acre university campus sits on three land grants given to other white individuals.

As she elaborates in her RGP podcast episode, Sanvitti Sahdev’s study of early timesheets and photographs documenting the construction of the first university buildings has revealed that many of the individuals who built and maintained the campus were Black and/or Hispanic men. Although she was able to identify where some of these workers stayed on campus—in a densely wooded area near where Reckling Park is located—it is of key significance that we have not been able to learn much about them due to archival gaps, which speak volumes about the stories centralized and sidelined in the University's records.

Research member Marc Armeña turned to Southwestern Louisiana, where in the 1850s, W. M. Rice purchased 50,000 acres of land. As he discusses in his RGP podcast episode, the Rice Institute’s Board of Trustees established the Rice Land-Lumber Company in 1911 to manage the land. Profits from the selling of timber rights, clear-cutting, and oil drilling funded and continue to fund Rice University, boosting the endowment by tens of millions of dollars. His research spans from issues of environmental racism and extractive capitalism to the struggles and organizing of the Brotherhood of Timber Workers—a labor union that in 1911 and 1912 recruited thousands of Black and white workers in a region marked by racial and social segregation.

AR: The group researching the William Marsh Rice Memorial (WMR Memorial) has been examining the early discussions about honoring W. M. Rice on Rice campus. An early conversation is in a letter from William Ward Watkin, one of the architects in charge of designing the first phase of the campus, to the then Rice president Edgar Odell Lovett. In the letter, Watkin recalls their prior conversation about incorporating parts of W. M. Rice’s downtown Houston home—its stairway, some of its trimmings, doors, and millwork—into the President’s House, making it a Founder’s House. Watkin wrote, “If this were done, then you would be freer to consider the further memorial to the founder in connection with the residence, or adjacent to the residence...” [2] In other words, the President’s House would be the WMR Memorial, either physically through the reuse or replications of elements from Rice’s former home, or through a memorial in, say, the president’s private garden.

Another key facet of studying the WMR Memorial is contextualizing its installation within the racialized climate of the late 1920s and early 1930s. Morgan Seay, another RGP member, has researched the 1930 iteration of an (at the time) annual event called the May Fete, which occurred a month prior to the memorial’s unveiling on June 8, 1930. She speaks about it in her RGP podcast episode. The campus was turned into a mock-plantation for a “colonial” themed celebration, replete with a highly racist performance and a replica of a plantation mansion designed by an architectural student and President of the Architectural Society. 3,500 Rice community members and Houstonians attended. When thinking of the memorial’s history and placement, we must keep in mind that at the time of the memorial’s unveiling, slavery and what we now know as anti-Black racism were casually present on campus.

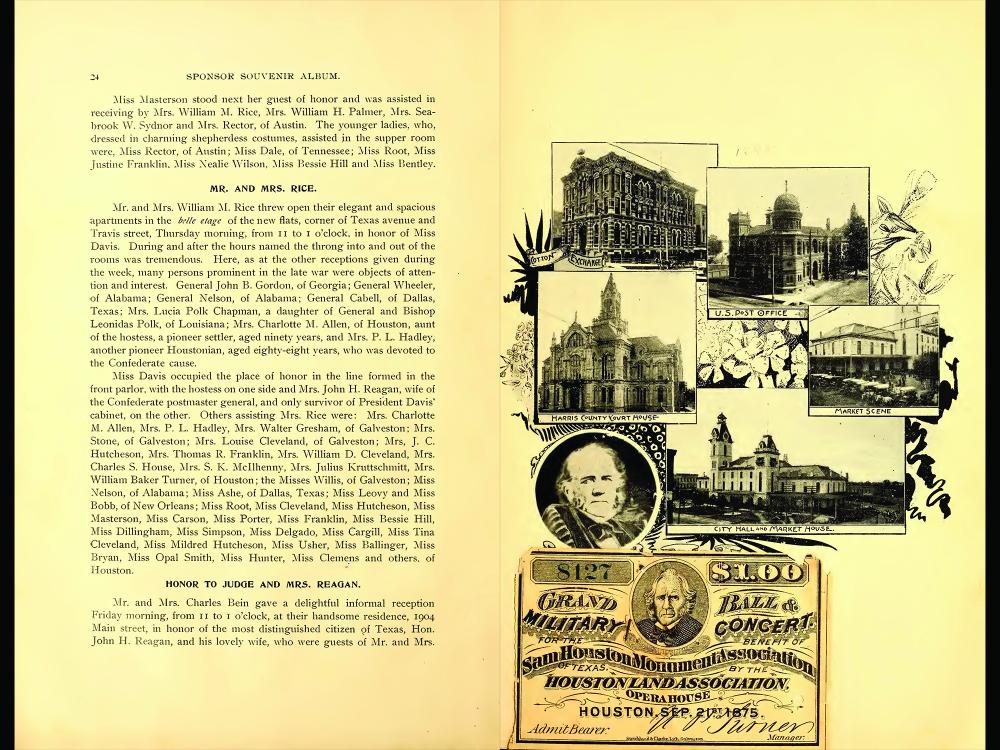

FLD: The fourth research group that Morgan is a part of, Performing White Supremacy, traces instances of overt nostalgia for the antebellum era and the Confederacy, which transpired on Rice campus well into the 20th century. Sumin Hwang has been researching the connections between Rice Institute and the nostalgia for the Confederacy, including the celebration of a holiday in its honor on campus, as well as W. M. Rice’s involvement with the Confederacy after the Civil War through the 1895 United Confederate Veterans Reunion in Houston. He and his wife held a reception at their apartments downtown for Varina “Winnie” Davis, a known idol among the Daughters of the Confederacy and the youngest daughter of Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederate States. Mrs. W. M. Rice also planned a city-wide Flower Parade and rode in the leading parade float with Davis.

In addition to other instances of overt white supremacy on campus like the presence of the Second Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, this research group has looked into Hanszen College’s Minstrel Gala. This was a popular series of events in which students donned blackface and acted as racist caricatures, told racist jokes, and were entertained by blackface choirs performing songs such as “Dixie” and “Pick a Bale of Cotton.” The Minstrel Gala took place over four years until 1965, the very year that the first Black professor and undergraduate students arrived at the university, though it would not be the last instance of blackface on campus.

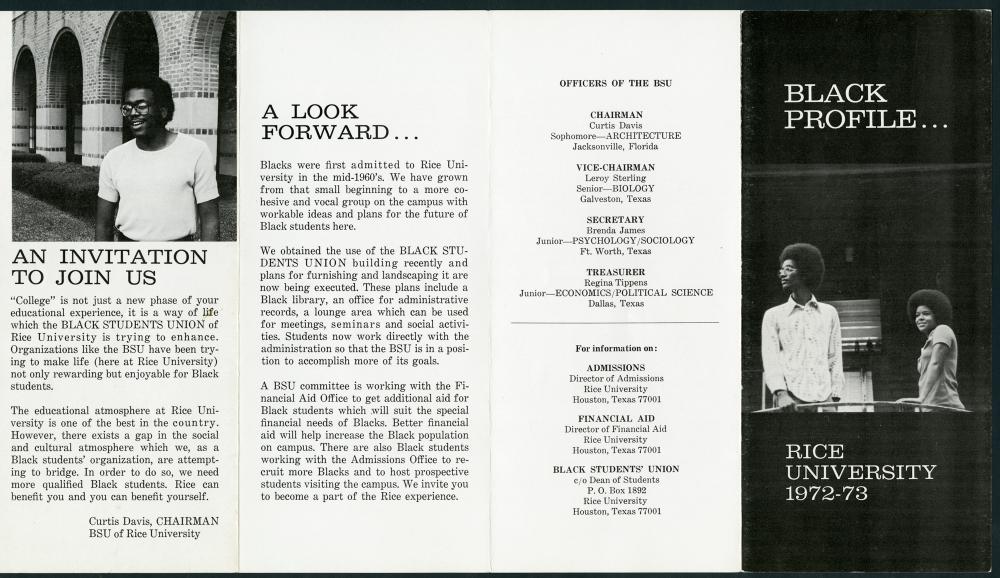

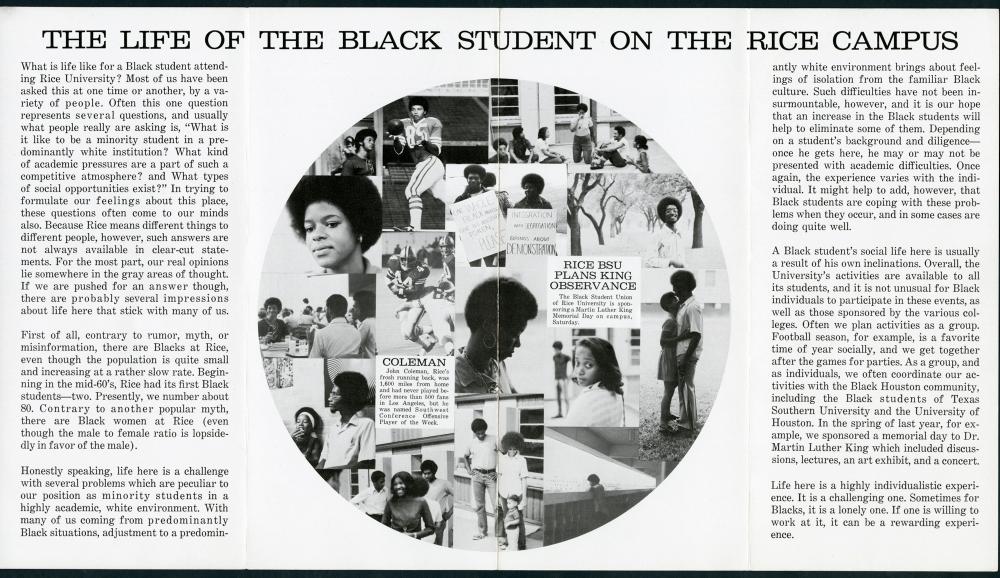

AR: The fifth group researches Early Black Life at Rice. Through archival research and interviews with the first Black students and professors to join the university, their work reveals long-standing activism of Black student organizations, as well as insightful assessments by early Black faculty members on the negative impact of the university’s overwhelming whiteness on its intellectual life. This group honors Black achievement at Rice while recognizing moments of daily resistance and, more than anything else, plumbing the changing texture and significance of Black community at the university. As one of four RGP Fondren Fellows, Venus Alemanji has been researching early Black women professors at Rice including Dr. Rose Marie Brewer, who joined the university as Visiting Assistant Professor in Sociology in 1974. At the time, her work focused on the Black community, social change and mobility, and political and urban sociology. Another figure in Venus’s research is Dr. Beverly Harris-Schenz, who noted of Rice in 1980 when she was the university’s only Black faculty member, “I don’t think it’s diverse at all. On the contrary, I think it’s one of the most homogeneous environments I’ve ever been a part of.”

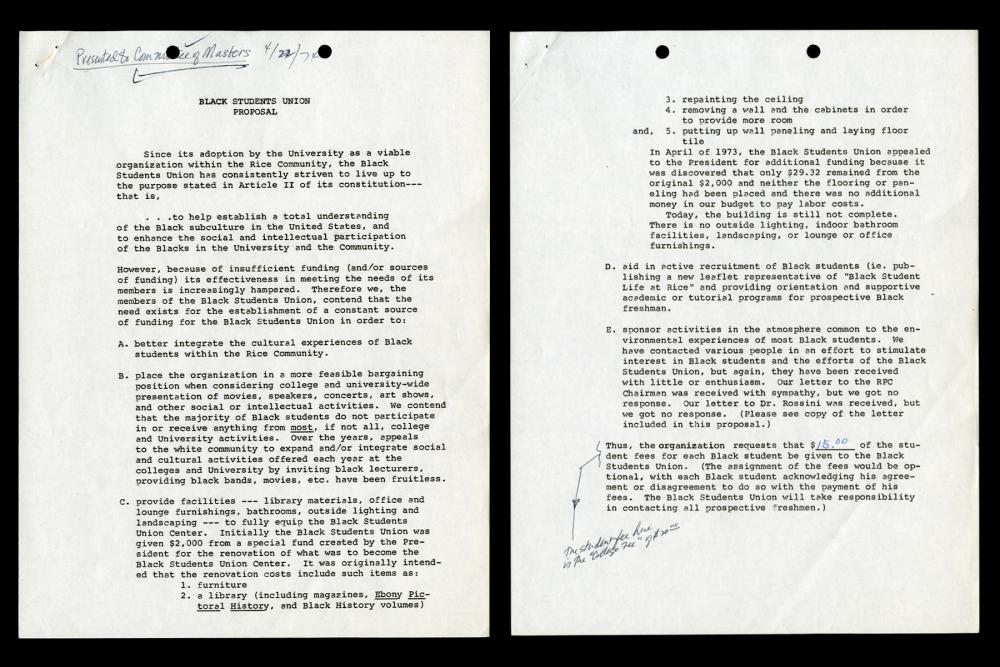

This group doesn’t only focus on professors; some of the earliest Black individuals on campus were staff members, and Lynne Lee has been studying early activism by Black students, including but not limited to the momentous formation of the Black Student Union in the early 1970s. As she elaborates upon in her RGP podcast episode, the BSU’s purpose as outlined in its constitution was “to help establish a total understanding of the Black subculture and to enhance the social and intellectual participation of the Black students in the University and the community.” [3] Despite the numerous hurdles, the students laid phenomenal groundwork for celebrating Black culture and spaces on campus, and for dealing with issues that Black students at Rice continue to grapple with and protest.

Can you tell us about the RGP’s podcast?

FLD: We thought one effective way to disseminate our research findings would be to launch a series of podcast episodes that has innovative forms of collaboration with local artists. Each episode is about a research topic developed by one of the RGP student members. We released eight episodes last year, and we are planning to launch eight more later this summer.

The first external artist to join the RGP’s efforts is Lisa E. Harris, an interdisciplinary artist, creative soprano, and researcher who has been receiving worldwide attention for her work in experimental opera and environmental justice. In an initial and very inspiring conversation, we visualized the possibility of collapsing both historical research and art activism. To kick off the collaboration, we asked Li to write an original sound composition and performance that she titled “New Freedom Remix,” which opens and closes each podcast episode. We are also enthusiastic about a larger collaboration with Li and the Rice Moody Center for the Arts.

What has the RGP’s research uncovered about events and practices on Rice campus?

FLD: There was a continued debate about whether the infamous photo in the 1922 Rice Institute yearbook of the “Rice Koo Klucks”—as the Institute’s Ku Klux Klan group was called–was taken on campus. Many people questioned the legitimacy of the photo despite it being signed by A. Klucker, who photographed Klan initiations and other events across Texas. The photo shows twenty individuals wearing Ku Klux Klan hoods and robes bearing the Klan cross insignia, posing at the entrance of a building with particular architectural features. Trained as an architect and architectural historian, I thought it would not be difficult to identify the building. After searching the campus on foot without success, I examined the detailed architectural blueprints and old photos of existing and demolished buildings in Woodson archives, which are included in a relational database organized by my colleague Farès El-Dahdah. One evening, there it was: the building behind the “Koo Klucks” was the Rice Field House, built in 1920 (where the Wendel D. Ley Track and Holloway Field is located) and demolished in the early 1950s. It was designed by Watkin, who was the supervising architect for the architectural firm Cram, Goodhue, and Ferguson.

How does Rice’s efforts compare to those of other colleges and universities in the US?

AR: Universities in the US and beyond have been grappling with their relationship to enslavement with increasing vigor (though many universities have been grappling with this for a century). The Universities Studying Slavery (USS) consortium currently consists of eighty-seven member institutions that are actively conducting this work, from the Citadel (The Military College of South Carolina) to Harvard. Of predominantly white institutions, Brown University was one of the first to begin studying and addressing its relation to enslavement in 2003. Princeton University, the University of Virginia, and the University of the West Indies in Barbados are among other universities that have installed monuments about these histories. More recently, Georgetown University announced a reparations fund to benefit the descendants of enslaved individuals once sold by the school. We are grateful to President David Leebron for forming Rice’s Task Force on Slavery, Segregation and Racial Injustice in June 2019, which, crucially, does not only focus on enslavement. Now thankfully we are at a point where, as Dr. Byrd nicely puts it, we are also grappling with the question: "What happens when we know a fuller truth about ourselves, and what can and should we do about it?”

The Task Force has released a report about the fate of the Founder’s Memorial, stating it was “unanimous that the Academic Quadrangle needs bold change” and “unanimously recommend[ed] the commissioning of such a redesign through a competition.” What is useful or of interest to the RGP’s work from this report? The document didn’t go so far as to unanimously recommend the removal of the statue of William Marsh Rice. Does the RGP have a position as to how this central public space of the university could be improved?

FLD: Adrienne and I are convinced that contextualization is not enough. As architectural historian Lucia Allais argues in “A Questionnaire on Monuments” published in October No. 165, it is key to not only consider the content and history of a particular monument, but also that the monuments have been “instruments of territorial management, penetration and control.” Monuments constructed about a century ago to honor individuals “were not only historical portraits. They were signposts, markers used to attract and repel certain constituencies, affect housing policies, and anchor planning decisions.”

Relevant scholarship from the last twenty years in art and architectural history as well as in museum and cultural heritage studies have informed resolutions taken by the very institutions in charge of the preservation of monuments and historical sites, such as UNESCO and the Heritage Conservation Committee of the Society of Architectural Historians (SAH). In the summer of 2020, the SAH published an official statement of support and encouragement for the removal of monuments that “express white supremacy and dominance, causing discomfort and distress to African American citizens who utilize the public spaces occupied by these monuments.” Confederate monuments are the clearest example of these types of monuments but not the only ones. Monuments and their relation to history are currently up, and in our opinion should always be up, for (re)consideration with a new and sanctioned dynamism—a dynamism that permits change and acknowledges that preservation (even with contextualization) isn’t always the right answer.

AR: We are pleased that the Board of Trustees has provided a significant window for change. Moving the memorial from its centralized place and contextualizing it, and the construction of a new memorial to commemorate the integration of the university, are necessary first steps to reimagining the Academic Quad as a vibrant and inclusive space. Of course, there are other symbols in the Quad that should be weighed in this conversation, such as the relief of Francis Galton, the so-called father of modern eugenics, which is carved on one of the capitals of the Lovett Hall’s colonnade. Why eugenics in the Academic Quad? Well, if you read Lovett’s inaugural speech from 1912, he identified eugenics as one of the applied sciences central to the university’s curriculum along with engineering, economics, and education itself. We need to grapple with the multiple histories that coexist within the space—and the ways in which they shaped the institution and continue to shape our present.

The RGP has been conducting research that could inform ways of contextualizing the statue in its future location, as well as make other histories visible. In addition, we have been actively thinking about how the Academic Quad could itself become a counter-monument. That is, a form of monument that does not aspire to permanence and solidity, but embraces change over time; one that encourages critical, ongoing conversations about histories and stories worthy of commemoration and their role in our present; one that engages in a dialogue with the existing memorial; one that could address how the university is not only indebted to Rice as a founder but also to the innumerable enslaved individuals through whom he built his fortune, to the workers that constructed and maintain the campus, and to the diversity of its community today; one that allows us to keep the conversation going.

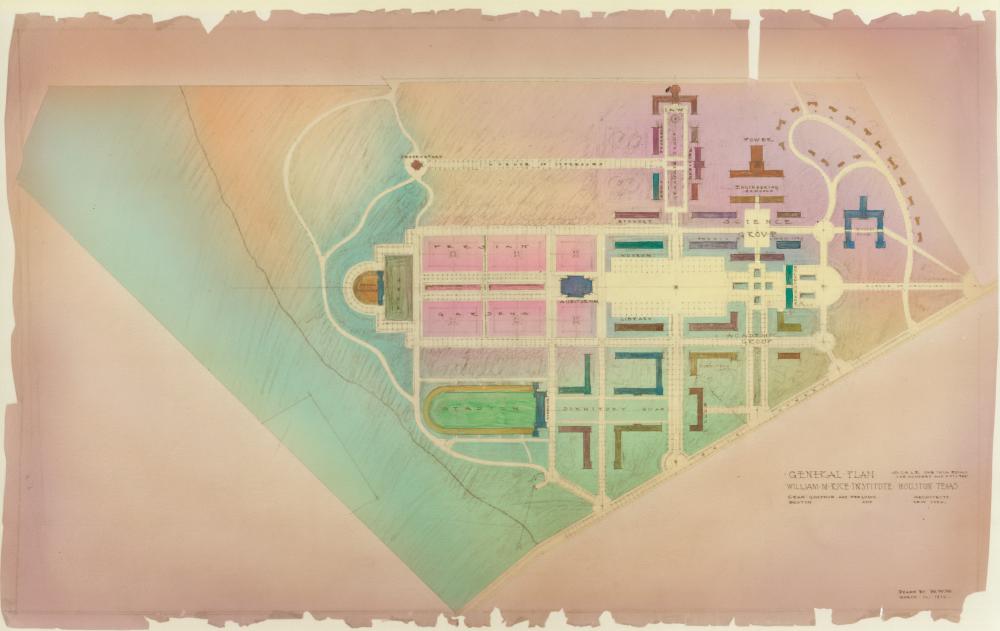

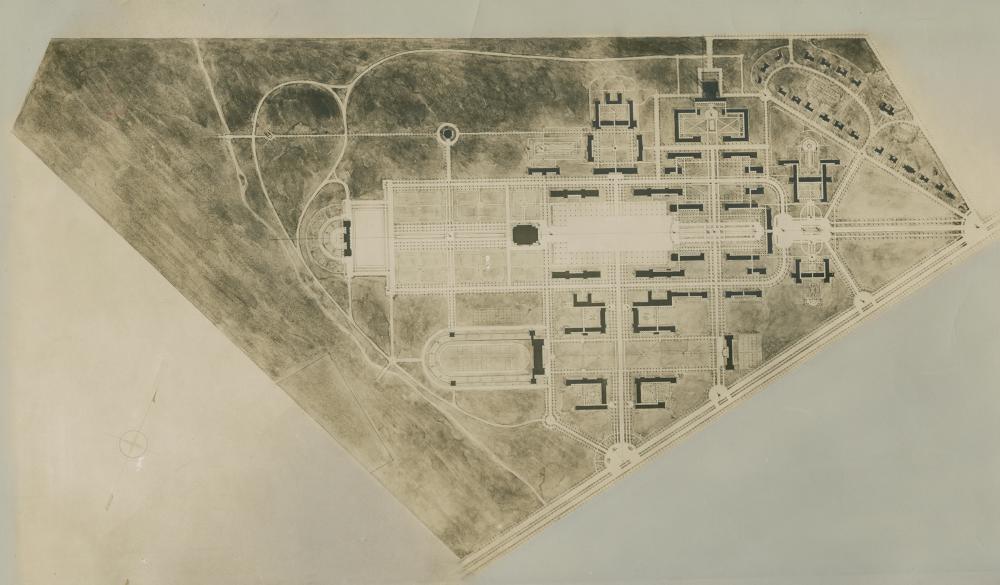

FLD: We found an early urban plan for Rice campus that could serve as an inspiration for a counter-monument. In 1910, Cram, Goodhue, and Ferguson were imagining an academic quadrangular entirely as a garden, labeled “Persian Gardens.” As the epicenter of the University has moved to the West (towards the other side of the Fondren Library), can we reimagine the historical Academic Quad as a series of conceptual gardens, honoring the traditions of the gardens tended by enslaved individuals? As I have learned from Adrienne’s research, enslaved people across the Americas to different extents have planted, tended, and cared for their own gardens where they grew their food, nurtured their environment, and nourished their cultural and spiritual identities together with their bodies.

Another garden could celebrate people like Elias Ramirez, who worked as part of the Rice Grounds team for over four decades (1913–56), and was also an early hero of Mexican-American civil rights in Texas. He established the Sociedad Mutualista Benito Juárez to help newly arrived Mexican immigrants become American citizens. He also worked for the establishment of Hidalgo Park in the East End of Houston, one of the early parks accessible to the city’s Latino community. In 1999, the Texas State Senate named a state office building in downtown Houston after Elias Ramirez, but he has not been commemorated at Rice as far as I know.

AR: Houston parks were officially segregated in 1922, but even before, as Giovanna Bassi Cendra’s research has shown, Hermann Park’s original deed stipulated that it could only be used by white people. Its deed! This was akin to the deed restrictions that banned non-white people from owning or renting property in the surrounding residential neighborhoods. The park was presented to the City of Houston by George Hermann in 1914, adding significant green space for the students of the neighboring whites-only Rice Institute and enriching the quality of life for Houston’s white population. Her research shows that at least two Black families were subjected to a public pressure campaign so that they would agree to sell their properties, which lay in the middle of the donated land, and move out. Jennie Pettit, who worked as a laundress for Rice students, was among these individuals.

FLD: In a recent conversation with Charles Landgraf, a member of Rice’s Board of Trustees, I was delighted to hear that he and Paula Sanders, a professor in the History Department, have for years imagined the Academic Quad as a pollinator garden. There are successful examples of gardens as counter-monuments at other universities, like the new garden at Princeton University that honors Betsey Stockton, a woman who was enslaved at Princeton and who made significant contributions to the university after gaining her freedom. The garden not only honors Stockton and makes a bold statement about Princeton’s commitment to equality, but it also contributes to the process of restoring the native ecosystem of the area. Rice’s Academic Quad as a memorial garden could also work as a pedagogical tool—one which not only permits stories such as those we have mentioned to be taught in the fresh campus air, but also presents little-recognized botanical histories of indigenous communities, of agricultural techniques transplanted from West Africa via the Middle Passage, or of collaborations between fugitive enslaved people and indigenous communities in the Gulf Coast.

What lies ahead for the RGP?

AR: The narratives that the RGP aims to tell are not limited to the contextualization of the W. M. Rice Memorial and the Academic Quad; our project expands across campus and beyond it. Working from Édouard Glissant’s position that the “landscape is its own monument,” [5] we understand the land and built environment as storytellers (we discuss this in our contribution to Rice Architecture Assistant Professor Brittany Utting’s forthcoming book, Architectures of Care: From the Intimate to the Common.) Our work has revealed myriad of significant sites that should be included in the conversation, which will allow us to tell a different story of Rice’s campus—one that acknowledges the history of racism as well as resistance embedded in our surroundings. This will be a crucial endeavor in the process of redress and building a more affirmative university for students, faculty, and staff of all backgrounds.

The Racial Geography Project is an initiative of Rice University’s Task Force on Slavery, Segregation and Racial Injustice. The Research Collective studies and unveils histories of racism and resistance that are registered in Rice University campus—from its land and buildings to its monuments and relief.

This Research Collective is led by Associate Professor in Art and Architectural History, Fabiola López-Durán, and PhD candidate in Art History, Adrienne Rooney.

The members of the Racial Geography Project past and present are Venus Alemanji, Marc Armeña, Malaika Bergner, Giovanna M. Bassi Cendra, Gabriella Feuillet, Dalia Gulca, Chaney Hill, Sumin Hwang, Spoorthi Kamepalli, Philip Kelleher, Emily Lampert, Lynne Lee, Amy Lin, Lauren Ma, James McCabe, Henry McMahon, Anthony Nguyen, Braden Perryman, Soha Rizvi, Sanvitti Sahdev, Morgan Seay, Karen Siu, Jared Snow, Amber Wang, Emily Weaver and Stephen Westich.

We are grateful to our supporters and interlocutors on campus, including Reto Geiser, Associate Professor in the School of Architecture, and his graphic design team; the Race and Anti-Racism Research Fund; The Humanities Research Center; The Fondren Fellows Program; and, of course, the chairs of the Task Force, Dr. Alex Byrd and Dr. Caleb McDaniel.

Notes:

[1] Harris County Deed Book N, pp. 53-54, Harris County Clerk of Court, Houston.

[2] Letter from WM Ward Watkin to President Edgar Odell Lovett, November 13, 1923. Box 37, Folder 9, Rice Institute President Edgar Odell Lovett papers, Woodson Research Center, Rice University, Houston, TX.

[3] Black Students Union Proposal, c. 1973. Box 1, Folder 3. Rice University Black Student Association Records, Woodson Research Center, Rice University, Houston, TX. 16 Sep 2020.

[4] The arch on the left was the backdrop for the infamous Rice “Koo Klucks” club photograph published in the 1922 Rice yearbook, the Campanile, picturing about twenty individuals wearing Ku Klux Klan hoods and robes. We have chosen not to reproduce the photo in this post, which is captioned as follows: “The Ku Klux Klan of Rice Institute / ‘The Year the Owls Were So Bad’.”

[5] Édouard Glissant, Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays (The University of Virginia Press, 1992). 11.

![Rice Digital Scholarship Archive. Courtesy Woodson Research Center, Rice University. [4] Rice Digital Scholarship Archive. Courtesy Woodson Research Center, Rice University. [4]](https://www.ricedesignalliance.org/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/images/inline/wrc01301_img%2020%20resized.jpg?itok=xytry2A3)