This review is part of a special series about preservation in Houston, edited by Helen Bechtel, published in connection with two national preservation conferences in Houston in November.

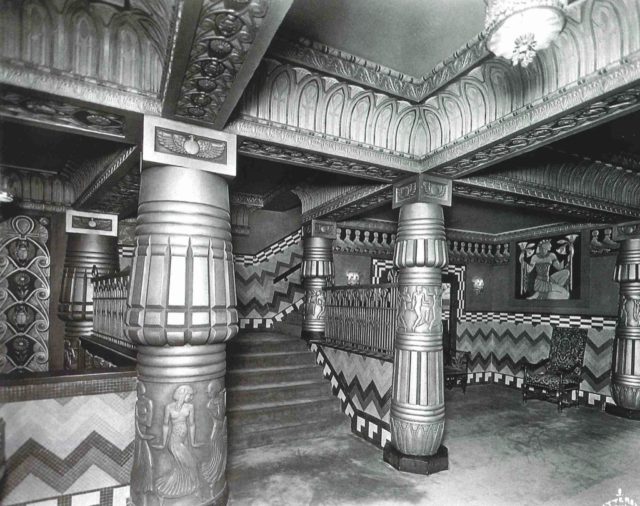

Houston has long been thought of as a city that only cares about its future, a city that tears down its old buildings, a city that disregards its history. It’s hard not to believe that, especially when you check the list of lost landmarks: art deco icons such as the 1929 Turn Verein, the 1934 Southern Pacific depot with its monumental murals of Texas history, or the 1938 Jeff Davis Hospital --- or the stunning midcentury modern 1949 Shamrock Hotel in all its glitzy décor, or the 1952 Prudential Insurance Building with its Peter Hurd mural, now relocated to Artesia, New Mexico. Perhaps most mourned by locals are the quartet of 1920s movie and vaudeville palaces --- the Italianate 1923 Majestic (John Eberson’s first atmospheric theater), the Adamesque 1926 Kirby, the Louis V 1927 Loews State, and the marvelous Egyptian 1927 Metropolitan. Out of this list of the lost, only the Shamrock drew loud voices of protest from Houstonians.

And yet this reputation is itself a relic. Houston has turned a corner. After half a century of organizing, we now have a preservation culture and laws to protect parts of the built environment. This may be hard to believe, but I will argue that no other city in the country has such an opportunity to become ground zero for the future of the preservation movement. Now is the time to shift from lament to action.

Julia Ideson Building, Tudor Gallery. Photo: Barry Moore

Julia Ideson Building, Tudor Gallery. Photo: Barry Moore

Gulf Building postcard. Photo: Houston Metropolitan Resource Center

Gulf Building postcard. Photo: Houston Metropolitan Resource Center

The two-story Magnolia Building (far right) is the only surviving part of the complex. Photo: Courtesy Bart Truxillo.

The two-story Magnolia Building (far right) is the only surviving part of the complex. Photo: Courtesy Bart Truxillo.

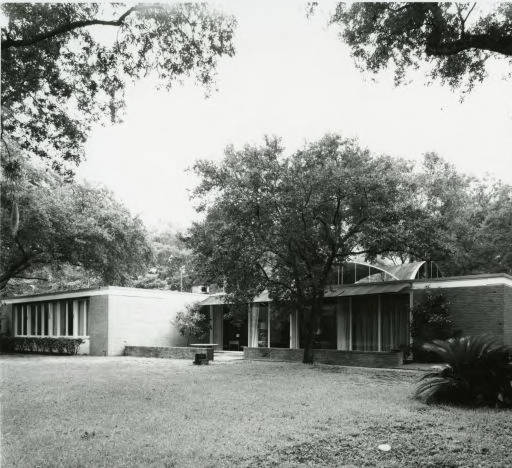

Menil House. Photo: Balthazar Korab, courtesy, The Menil Collection, Houston

Menil House. Photo: Balthazar Korab, courtesy, The Menil Collection, Houston

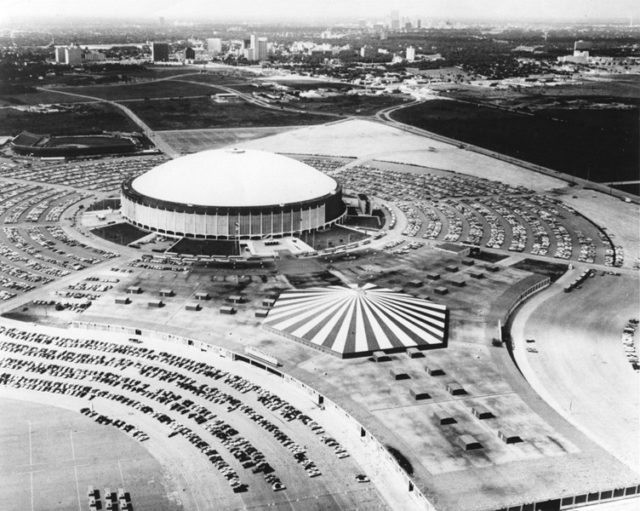

Astrodome, 1970. Photo: Houston Metropolitan Resource Center

Astrodome, 1970. Photo: Houston Metropolitan Resource Center

Houston seems younger than it is. Few would guess that our founding by the Allen Brothers was within a few years of Chicago’s. Why does Chicago seem so much older? The answer is complex. Perhaps it has to do with how commercial trade and land speculation have been part of our DNA from the beginning. Houston also grew at a relatively slow pace compared with Chicago in its first 80 years. And, as I pointed out above, so much was demolished before the preservation movement, locally and nationally, had even begun to develop into the force it is today. As a result of all these factors, perhaps more than in any other major city, Houston has and must continue to puzzle through the preservation of the “Space Age,” Modernism, and Postmodernism. Houston has had to and must continue to go beyond the preservation of narrowly defined monuments. We are working towards preserving communities of color and integrating new immigrant stories into an already remarkable mix. We have and will continue to preserve the history of the future.

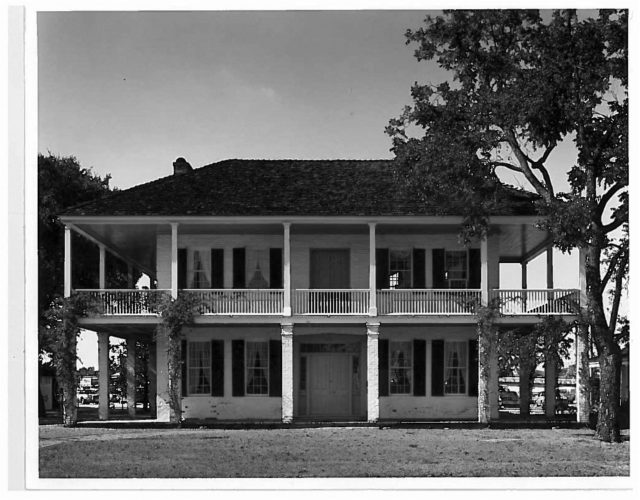

Phase 1 --- Picking Our Battles and Saving What We Could

The preservation movement in Houston grew slowly but incrementally. In 1954, an embryonic Harris County Heritage Society appeared, originally to preserve just the 1848 Kellum Noble House, the oldest brick structure in Houston, and still in its original location, which when new was outside the town limits. The original founders, Harvin C. Moore, architect (my father), Faith Bybee, (sister-in-law of Moore), and Marie Phelps, were longtime Houstonians, motivated by a sense of history as well as nostalgia --- the site became the city’s first public park in 1900, and the house, incredibly enough, housed its first zoo. The nonprofit was formed to raise funds for its restoration. Within a few short years other threatened structures were identified, purchased, and moved into Sam Houston Park and restored. Today there are 10 buildings on display, where a visitor can get a feeling of what domestic life was like from the days of the earliest settlers to the first decade of the twentieth century. One of the most visited houses was built in 1877 by Pastor Jack Yates, a former slave, and founder of nearby Freedmen’s Town, and Antioch Missionary Baptist Church. Like many other communities, preservation efforts in those decades were almost exclusively focused on domestic structures.

It was one thing to attract volunteers to a heritage society, but quite another to get the attention of the city and its developers who controlled many of Houston’s important historic buildings.

The tiny cadre of preservationists, made up of historians, committed volunteers, architects, and planners, became increasingly aware of preservation elsewhere in more historic spots and organizations such as the San Antonio Conservation Society, the Galveston Historical Foundation, and the Vieux Carre Commission. The great battles elsewhere provided inspiration and courage: the proposed Riverfront Expressway in New Orleans and the unsuccessful Olmos Park/Breckenridge Park vs. US 281 case in San Antonio. These three cities had bigger, older preservation communities that fully embraced their past. The Houston folks had to sell the concept that there was a past worth saving.

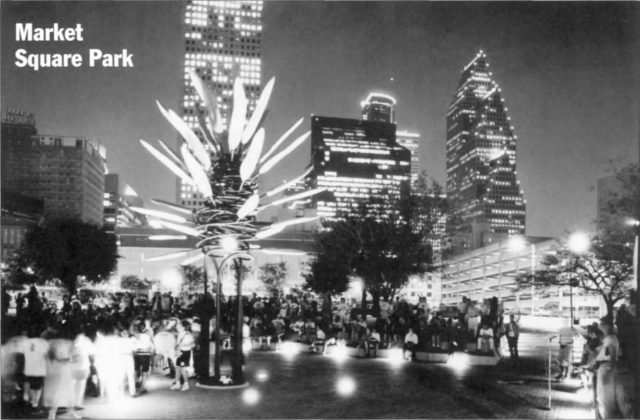

Houston preservationists, without normal tools of city planning and zoning, zealously continued their mission utilizing the only tools they had --- cajoling and bartering. They chose the battles that mattered the most. The first great one was the saving of Market Square.

Market Square was the original heart of Houston. The Allen Brothers intended the capital building of the new republic to be there, but when a different location on Main Street was chosen, they designated the site for municipal use. Market Square was home to City Hall and a market from 1841 until 1939, when the current Art Deco version was built a few blocks away. By 1960, the old 1904 City Hall, used then as a bus station, was demolished and replaced by a parking lot. When the mayor proposed selling the block to a hotel chain, the community rose up, persuading City Council to keep Market Square in city hands. The block was later redesigned as a park with funds from Houston Junior League, and has now been revitalized a third time as a thriving, populated urban neighborhood park, with help from the Projects for Public Spaces. It has evolved into a well-loved centerpiece of the Main Street/Market Square Historic District.

Another important battle concerned the 1869 Pillot Building, Houston’s oldest cast-iron building, in county hands since the 1970s. Desiring the 5,000-square-foot site for office expansion, Harris County seemed set on a demolition by neglect course. Efforts by the new Greater Houston Preservation Alliance (now Preservation Houston) convinced Commissioners Court to advertise the property to developers, offering a long-term lease. By the time a successful bidder was identified, much of the masonry structure had collapsed. The building was demolished, but all cast-iron elements were salvaged and incorporated into the new reproduced building. Unfortunately, the developer was no longer entitled to his historic tax credits due to the loss of much historic fabric.

Phase 2 --- A Movement Gains Its Footing and Sets an Agenda

Soon, the preservation situation began to change. Thanks to the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, which codified public sector involvement, Houstonians began listing and landmarking sites in the National Register of Historic Sites. Houston today claims 269 buildings, 12 districts, and 8 bridges in the National Register, and more are on the way.

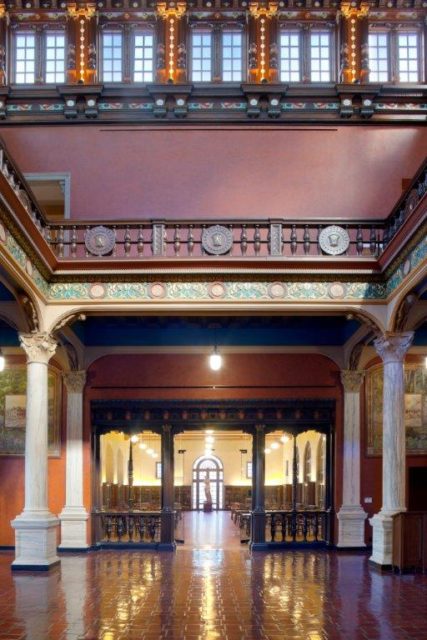

In 1974, the Houston Metropolitan Research Center was formed through cooperative efforts of the Houston Public Library, Rice University, the University of Houston, Texas Southern University, and the Southwest Center for Urban Research, and was supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Houston Bicentennial Commission, the Brown Foundation, and Houston Endowment. The HMRC, housed in the recently restored Julia Ideson Building, maintains a professional and volunteer staff of historians, archivists, librarians, and conservators. At present the collection contains more than four million photographic prints and negatives, 150,000 sheets of architectural drawings (the largest collection in a public library), hundreds of maps and countless books and papers related to local and regional history. The collection has proved to be an invaluable resource for property owners, developers, architects, and historians. It can be said that every restoration project in Houston begins in the HMRC.

In 1972, the Houston Chapter of the American Institute of Architects undertook the research and publication of the first Houston: An Architectural Guide, in conjunction with the national AIA convention of that year. Now in its third updated version, the guide, written by Stephen Fox, is an invaluable resource for everyone involved with the built environment.

Though Houston developers and property owners were much slower to embrace preservation than their peers in other cities, the tax legislation of 1976, which provided credits for qualifying structures in the National Register, provided the expected preservation stimulus here. In fact, in 1980, Texas National Bank of Commerce, now J.P. Morgan Chase Bank, owner of the 1929 Gulf Building, completed a $50 million certified rehabilitation, the largest tax credit project in the country that year. The Gulf Building, designed by Houston architect Alfred C. Finn, was directly inspired by Eliel Saarinen’s second-place entry in 1922 for the Chicago Tribune Building design competition. The building and its interiors constitute Houston’s most splendid example of the commercial Art Deco style.

Smaller, early preservation projects took advantage of the tax credits soon after the act was passed in 1976. In 1981, contractor/developer Frank Glass restored the 1893 Kiam Building, a five-story commercial building with masonry walls, heavy timber construction and the city’s first elevator. The 1912 Union National Bank Building, and the 1904 Commercial National Bank Building soon followed. The 1921/1936 Humble Oil Building was renovated for a Marriott Hotel, the 1913 Depelchin Faith Home, originally an orphanage, was converted to condominiums, and the 1936 Clarke and Courts Building was redeveloped as apartments.

Even before the tax act projects were possible, there were a few landmark endeavors that were real game changers. In the early '70s, Bart Truxillo bought and restored the 1893/1912 Magnolia Brewery on Buffalo Bayou adjacent to the Main Street/Market Square Historic District. The popular restaurant Bismarck on the second floor demonstrated that Houstonians could dine in an elegant Art Nouveau environment that most people had forgotten existed. The 1884 Cotton Exchange Building, one and a half blocks away, offered for the first time modern office accommodations in a nineteenth-century historic building.

But the biggest impact was made by the restoration and renovation of the 1913/1927 Rice Hotel for apartments, restaurants, bars, and special event rooms. The Rice, by far the largest building in the historic Downtown, had sat empty for more than a dozen years, casting a dismal and discouraging shadow over its old neighbors. The hotel is historically famous for several reasons: it sits on the original site of the first Capitol of the Republic of Texas; it was the first "modern" first-class hotel in the city; its final wing was completed in time for the 1928 Democratic National Convention; and, most recently, it was the site of President Kennedy’s last stop in Houston before his assassination in Dallas the next morning. The Rice project was an undertaking of Mayor Bob Lanier and the Houston Housing Finance Corporation in partnership with Randall Davis in 1996. The success of the renamed Rice Lofts at last made historic preservation desirable and safe, and it specifically stimulated residential conversions downtown.

Phase 3 – Houston’s Preservation Takes Off

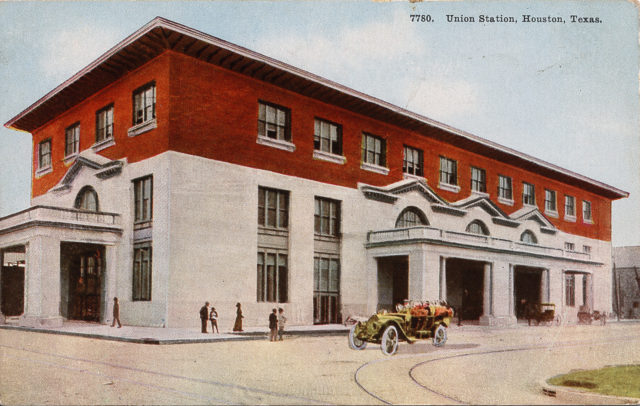

So much had the acceptance of historic structures entered the public consciousness that the 1911 Union Station was routinely incorporated as a lobby into the 1996 Minute Maid Park, home of the Houston Astros.

Through Historic Houston’s partnership with neighborhood groups, Mayor Bob Lanier was persuaded in 1995 that Houston needed to protect the city’s historic resources. The first preservation ordinance was heavily lobbied by real estate and developer interests, resulting in a weak outcome. Nevertheless, just getting one was considered a major achievement at the time. During Mayor Annise Parker’s first term (2010-12) in a different political and cultural environment, a revised ordinance was passed that eliminated the ability to bypass Landmark and Historic District designations after a 90-day period. A Certificate of Appropriateness was required from the Houston Archeological and Historic Commission for any restoration, rehabilitation, addition, external alteration, or new construction in a historic district. In 2010 and 2015, again under Mayor Parker, the ordinance was revised, streamlining the process for approval, refining the list of projects eligible for the City of Houston preservation tax incentive and, for the first time, giving the ability of the Houston Archaeological and Historical Commission (HAHC) to deny demolition or insensitive exterior changes to contributing buildings in historic districts and to Protected Landmarks.

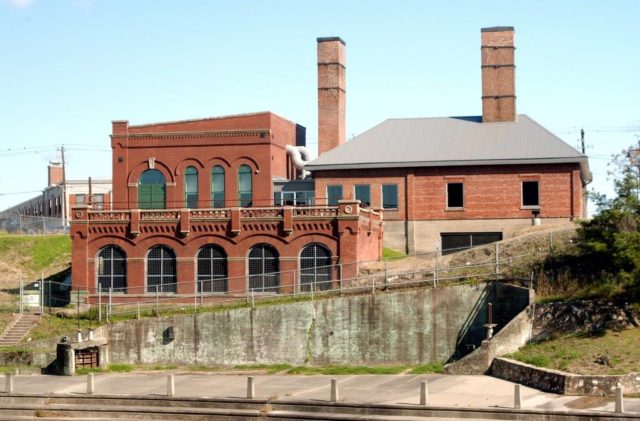

Houston’s major public buildings have a renewed life as restored civic monuments, including the 1912 Harris County Court House, the 1926 Julia Ideson Building (formerly Houston Central Library), and the 1939 City Hall. Other public and private buildings have been adapted for compatible, alternative uses, including the 1904 Willow Street Pump Station/1915 City Incinerator for a University of Houston Downtown conference center. The 1924 Jefferson Davis Hospital has been converted to artists’ lofts, the 1910/1941 Union Terminal Warehouse to the City Permitting Center, the 1924 Temple Beth Israel for a theater for Houston Community College, the 1940 Houston Municipal Airport for a museum of flight, and a 1949 car dealership for the Ensemble Theatre, one of only two professional African-American theater companies in the country.

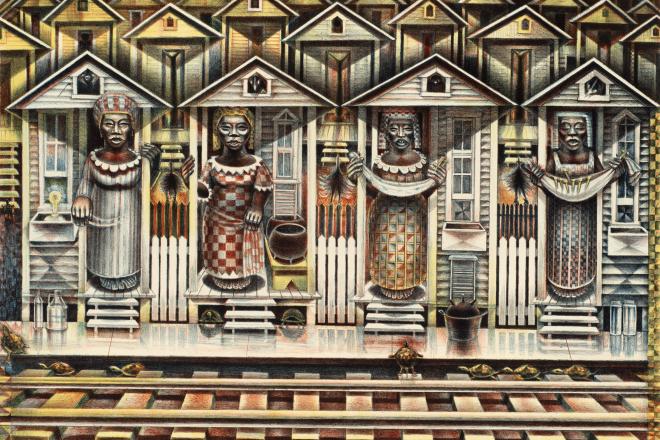

One of the most extraordinary phenomena in the '90s was the realization and restoration of Project Row Houses by artist Rick Lowe. Completed in '94, it comprises two city blocks and 22 shotgun houses built in 1939. Located in the city’s historically African-American Third Ward, they function as a place for art making and exhibition, community involvement, social service provision, historic preservation, and neighborhood revitalization. Project Row Houses has become a model for many other artist-based community initiatives. Lowe might not consider himself a “preservationist,” but his work, and that of others, has reshaped the whole conception of the preservation movement. It’s not only about saving windows and corinthian columns on the buildings of the elite.

Phase 4 — Houston Preservation Lands on the Moon

Most of Houston’s preservation efforts have focused on pre-World War II buildings. However, given how limited that stock is here, in the last decade a new preservation consciousness has started to take hold --- an awareness of midcentury modern architecture. Appreciation of the recent past always seems to skip a generation. Building owners and architects were quick to slipcover earlier commercial buildings to make them appear more "modern." Now, thanks largely to the Main Street programs and façade grants, slipcovers are slipping off, revealing finer features underneath.

One of the premier examples of midcentury architecture is Philip Johnson’s Menil House, designed for John and Dominique de Menil in 1950. It was his first Houston commission, and it brought Houston face to face with 20th century modernism in all its cultural aspects. The house was recently restored by Stern and Bucek Architects.

Part of the new trend here can be credited to Houston Mod, a modern architecture preservation group, founded in 2003. It has stimulated a popular interest in post-war architecture. The nonprofit has conducted surveys to identify and document a broad range of modern architecture in the city, including large numbers of buildings from the '50s and '60s. The website promotes a "Mod of the Month," highlighting recently discovered places, often for sale, and sponsors popular home tours. The organization has become a magnet for Houston’s Gen X and Millennial populations with an appreciation of the city’s recent history.

Steve Curry, one of the founders of Houston Mod, lives the life of a "Mod Man." He bought and restored the 1953 Bendit House, designed by Lars Bang, one of the first graduates of the University of Houston’s architecture program. Restored down to its blond paneling, plastic laminate countertops, and vintage car in the carport, the project has been recognized for its excellence by Preservation Houston, Houston AIA, and Texas Society of Architects.

In 2002, students in a preservation design studio at the University of Houston, under the direction of Anna Mod and me, conducted a historic resources survey of the Richmond Corridor, a rare seven-block concentration of early suburban office buildings of outstanding quality. The study provided timely documentation, as the area was experiencing pressure for new high-end development. The resulting publication, City Houston/Style Modern, sponsored by the Upper Kirby District, was distributed with the hope that owners and developers would come to appreciate the inherent architectural merits of the street.

More recently, the Architecture Center Houston (Houston Chapter AIA) mounted an exhibit, "Uncommon Modern," organized by Anna Mod with a host of picture-taking volunteers. The show focused primarily on midcentury buildings outside Loop 610 that were good, but of second-tier design quality, in the hopes that people would begin to look at their architectural surroundings with a more appreciative eye. With the help of the Susan Vaughan Foundation, a catalog was published to further spread the inspiration.

Preservation Houston has presented Good Brick Awards for outstanding projects since its founding in the late '70s. Over the years the award has become prestigious for commercial, institutional, and domestic buildings. In this decade, much recognition has gone to post-war projects, including the 1949 Weldon’s Cafeteria Building, the 1957 Farnsworth & Chambers Building (now the Gragg Building, home of the Houston Parks Department), the 1957 Sylvan Beach Pavilion, and the 1961 Oak Forest Neighborhood Library. At present, two major Downtown office buildings from the '50s are under renovation and restoration and are undoubtedly good candidates for future Good Bricks.

It seems obvious that the enormous growth experienced by Houston after World War II would have resulted in many existing buildings of every conceivable type and quality more than 50 years old. It represents a great opportunity for local preservationists to landmark those sites that represent the high tide of Houston’s dynamic growth. In fact, a recently revived preservation program at the Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and Design at the University of Houston, inspired by Dean Patricia Oliver, purports to focus on that opportunity to train future preservationists. No other city in the country has such an opportunity to become ground zero for midcentury modern restoration.

One of the most iconic additions to the National Register of Historic Places is the Mission Control room at the Lyndon B. Johnson Manned Spacecraft Center in Clear Lake. Opened in 1963, the room became known to the entire world via the televised moon landing in 1969. All of the original technology is still in place, down to the dial telephones and small black and white computer monitors. To walk through it today is to feel history unlike any other place in Houston. NASA was, after all, the most important creation of a midcentury modern America.

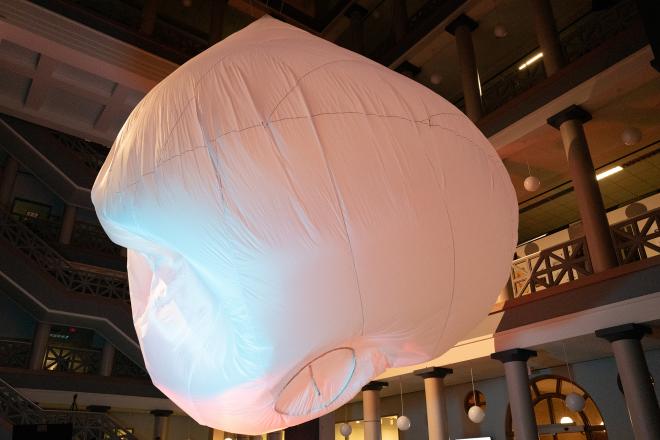

The other uniquely Houston iconic building is the 1965 Astrodome, the "Eighth Wonder of the World," an offspring of America’s quest for outer space. It was the first permanently enclosed, air-conditioned arena built to accommodate baseball and football. The steel-trussed roof spans 642 feet, 218 feet above the playing field. It was the second-largest dome structure in the world at the time. The Astrodome has been vacant since 2002 and was on the National Trust’s most endangered list until this year. Harris County Commissioner’s Court recently approved a $105 million budget for restoration and renovation, including $5 million for engineering studies to raise the original floor level to provide 1400 parking spaces, pending expected approval from the Texas Historical Commission. In addition, the Astrodome Conservancy, recently founded by National Trust board member Phoebe Tudor, plans to partner with the county to define future uses and identify potential donors.

In Houston in the early '60s, the dream of new worlds and new environments was real, and for the first time, the dream was all around us. After 1969, the future was the present, colored by plastic laminate, vinyl tile, supported by stainless steel, framed by aluminum, lit by sliding glass doors and skylights, with patios carpeted with Astroturf. We must preserve those best midcentury places, left over from the time when the sky had ceased to be the limit.

Barry Moore is senior associate with Gensler architects where he specializes historic preservation and in the design of theaters, non-profit, and educational facilities.

The original version of this article included summaries of the preservation ordinances passed under Mayor Annise Parker that were corrected. Most of the preservation provisions were in the original 1995 ordinance. The 2010 revision under Mayor Parker eliminated the 90-day waiver for historic districts.