Even though he’s developing the former Cheek-Neal Coffee Company Building on Preston Avenue, David Denenburg doesn’t think of himself as a developer. “I guess I’m a repurposer,” he says.

The term fits him, and it fits his project --- it suggests that there’s plenty of life left in in the 55,000-square-foot building, designed by Joseph Finger and James Ruskin Bailey and completed in 1917. A rendering of the project that Denenburg's not ready to publish shows a storage wing of the building, which now houses wheelbarrows and other tools, turned into a storefront and shared kitchen that would be used by food vendors operating stalls on the first floor; the top four floors would be furnished offices.

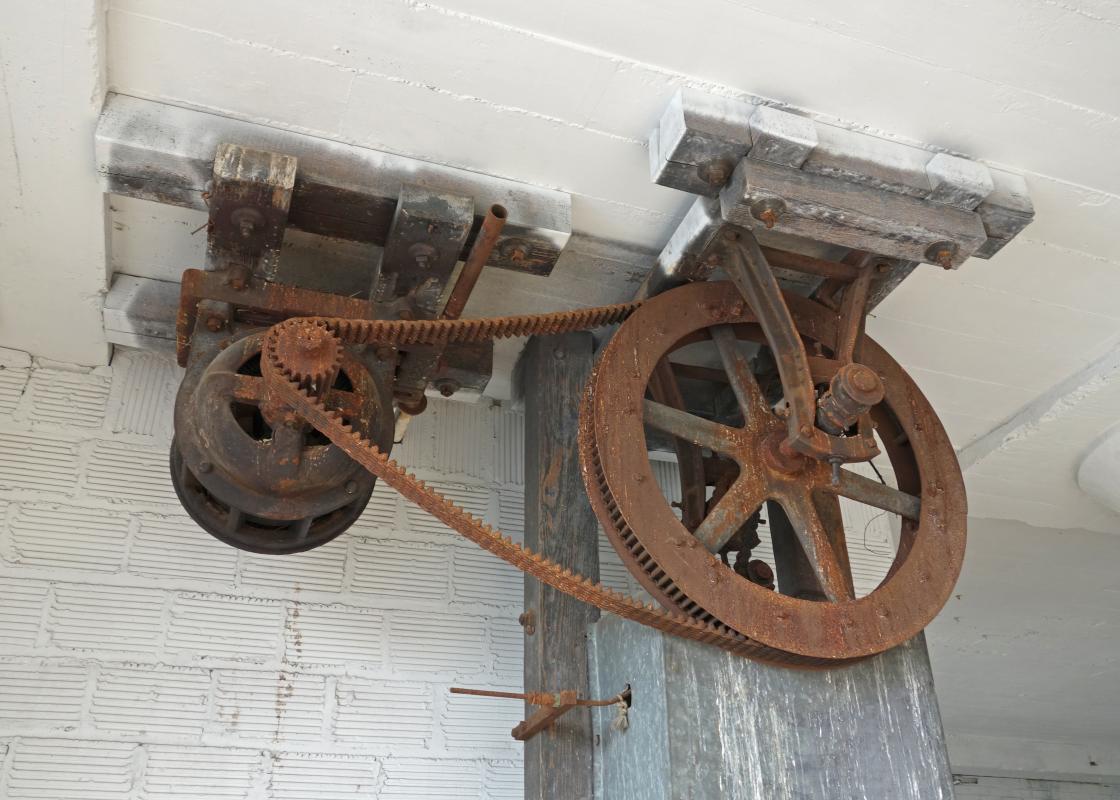

Denenburg has already envisioned ways of incorporating into this new concept the building's old machinery. The fire escape he imagines as a way for people to clamor up to the rooftop bar, where an icehouse would be carved out of the decommissioned water tower. A corroded boiler in the basement could find new life as a pizza oven; an internal four-story-high motor-driven chain could become a kind of hipster dumbwaiter delivering boiler-fired pizza up to the office workers. Even the forgotten steel rods jutting out of the facade, in place for an addition that was never added, Denenburg sees as useful. "They show the history of the place," he says.

"It’s one of the most beautiful buildings I’ve ever seen."

When I pressed him on that, wondering what, exactly, is so beautiful about it, Denenburg searched for words. He mentioned the “rawness” of its interiors, the way the floors are punctuated by heavy concrete columns ...

... and the way those columns carry the indentations of the rivets of what must have been sheet-metal forms:

“I just love old buildings. I love old things,” he says. “I like that it’s built so strong. And the detail is so different from what you would see today.”

My question reveals a blind spot on my part. Preservation, at least in this case, isn’t purely logical. It doesn’t happen on architectural merit alone. Stephen Fox, in the AIA Houston Architectural Guide, says the building "forthrightly expresses its reinforced concrete frame construction" (315).

True, but that doesn’t exactly get the blood pumping, at least not to the extent that it would take to replicate what Denenburg has gone through to become the owner of this building. Though the rationality of tax incentives and other economic considerations come into play, there’s also an element of passion --- irrational, inexplicable passion --- to historic preservation. “I’ve been calling about this building for 15 or 18 years,” Denenburg says.

Nancy Sarnoff reported in her Houston Chronicle story about this building that Denenburg was told by both "welders and architects" that the steel casement windows couldn't be restored. Denenburg has, for example, personally cut, welded, and bonded 74 new windows to replace the ones he personally yanked out.

But his biggest effort might have been to persuade TxDOT not to demolish the building in the first place. Early plans showed the right-of-way of a reconfigured I-45 running through this part of East Downtown. The Cheek-Neal would have been lost. Denenburg says that TxDOT officials have told him that the right-of-way was altered because of his efforts. Now, a deck park atop the depressed I-45, similar to Klyde Warren Park in Downtown Dallas, will essentially become the building's front yard.

This isn’t easy to do --- to pursue ownership of a building for the better part of two decades; to remake, by hand, its windows; to be the voice of dissent against a massive institutional force like TxDOT. But it’s not irrational. Repurposing buildings like the Cheek-Neal, as difficult as it’s been, as Jim Parsons of Preservation Houston writes, is “one of the smartest things we can do.”

“A lot of historic buildings were built to last, built with pride,” he writes in an email to OffCite.

A century ago, companies thought of well-designed and solidly built buildings as evidence of a well-run and trustworthy business. These days, for a lot of reasons, we tend to build anonymous manufacturing plants perched alongside freeways or hidden away in industrial parks. The Cheek-Neal is a great example of an industrial building that was designed to complement the cityscape. … When a building like the Cheek-Neal is lost, we never get another one like it, and we lose another example of the way people used to design and build.