In the long list of Houston’s long-gone places, one is especially evocative: Quality Hill, the city’s first elite residential neighborhood. It started in the mid-1800s when prominent businessmen built their houses around Courthouse Square, and from there it spread east and south, toward present-day Minute Maid Park and Discovery Green. Life in the neighborhood --- at least if you believe the writers of Houston: A History and Guide, the 1942 WPA guide to the city --- was something right out of the Old South:

Here the manner of life was thoroughly in keeping with the setting. Wealthy businessmen wearing high silk hats drove downtown in velvet-upholstered carriages, to spend a few hours in offices resplendent with red plush. In harness with gold or silver buckles prancing horses drew gleaming victorias as fashionable women took their regular afternoon drives. On warm days, ice tinkled in mint juleps. ...

And, like much in early Houston, it didn’t last. As the city grew, the wealthy moved farther south, building impressive mansions in the South End (the area now called Midtown) before decamping to suburban settlements like Shadyside, Broadacres and River Oaks. By the 1930s, old Quality Hill was no more, its gracious homes bulldozed or chopped up into cheap apartments, its gardens paved over for parking. These days it’s usually reported that only two Quality Hill homes remain: the Foley and Cohn houses, built in 1904 and 1905. Both are empty and the worse for wear, having been awkwardly shuffled around as development schemes have come and gone.

What many people don’t realize is that there’s another Quality Hill house standing today. It’s one of the most distinguished of all, and it’s still occupied and kept in pristine condition. The odd part, though, is that the house hasn’t been in Quality Hill for 110 years.

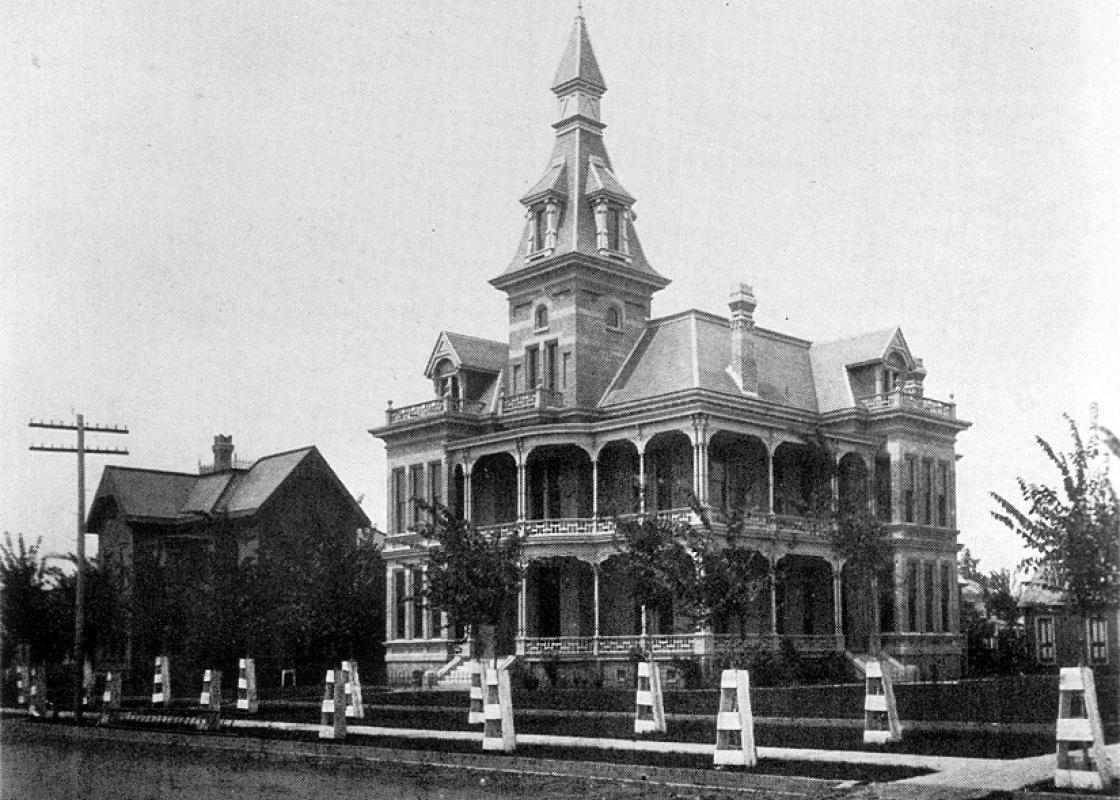

The survivor is the Waldo Mansion. Railroad executive Jedediah Waldo built it on the northeast corner of Rusk and Caroline in 1886. Back then the site was prime residential property, and Waldo wanted a house that was suitable for the address. Architect George E. Dickey designed a three-story brick house with elaborate double galleries, a roof bristling with dormers and balconies and a central tower that rose to the height of a five-story building. Heavily detailed interior woodwork of cherry, maple, oak, walnut and pine wouldn’t have looked out of place in the state capitol. Even among the homes of Houston’s upper crust, the Waldo house was a standout.

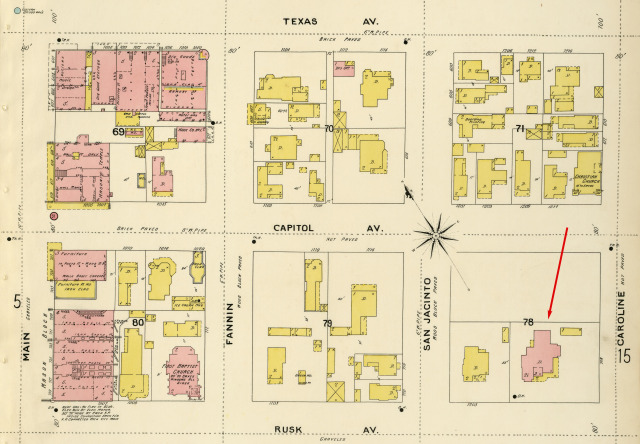

1896 Sanborn fire insurance map with original location of Waldo Mansion. Courtesy: Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.

1896 Sanborn fire insurance map with original location of Waldo Mansion. Courtesy: Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.

Jed Waldo died 10 years after the house was finished. The family continued living there, and although Quality Hill was still a solidly upper-class area, it was losing a battle with Houston’s expanding business district. The old houses around Courthouse Square were some of the first to go, replaced by office blocks and stores. As the century came to a close, commercial buildings sprang up farther south. Then, when local leaders began calling for construction of a new federal building and post office in 1902, the site chosen for the project --- a spot deemed to be at the forefront of Downtown development --- was the block where the Waldo house stood.

The government closed the deal with property owners on the block in late 1903; Mary Waldo, Jed’s widow, received $50,000 for her property. Neighbors moved, leaving their houses to be demolished, but Mary had a different idea. She ordered her home to be dismantled and rebuilt a couple of miles to the southwest, at 201 Westmoreland Avenue in the new suburban neighborhood of Westmoreland Place.

Overseeing the work was one of the Waldo sons, Wilmer, a Princeton-trained civil engineer. Wilmer redesigned the house in a stripped-down Italianate style, sans galleries and tower, but he made sure the original interiors fit in the new plan. “The architecture of the new Waldo home is so arranged that all the hardwood floors, finely polished casements, the doors, windows and other parts will fit into it,” The Galveston Daily News reported at the time. “It is therefore a case of taking a house down and putting it up again forty blocks away.” In a neat bit of symmetry, the house’s cornerstone (it has an actual cornerstone, complete with a time capsule) was laid at the new Westmoreland site 20 years to the day after it was originally placed in Quality Hill.

Construction on Waldo Mansion 2.0 wrapped up in 1905, and Mary Waldo and her four unmarried kids, Wilmer, Lula, Mary and Virginia, settled back into their old house. (Two other Waldo offspring, Gentry and Cora, had married and moved away.) Life seemed to have been pretty good for the family. Wilmer continued his civil engineering career; among his accomplishments was draining the swampy site where the Rice University campus was built and finishing the first sections of Rice’s inexplicably alluring utility tunnels. Lula, Mary and Virginia, collectively known as the “Misses Waldo,” ran a highly regarded private school for girls. As the decades passed, the Waldos grew old and died; by the mid-1960s, only youngest daughter Virginia survived. She sold the house to architect Clovis Heimsath in 1966 and moved into a retirement home, where she died eight years later.

In the 50 years since the Waldos left, their mansion has seen even more changes: designation as a Recorded Texas Historic Landmark in 1978; a role as Jack Nicholson’s pad in Terms of Endearment; and, of course, remodeling and restoration and new owners (the last time the house sold, last year, it fetched $2.85 million). These days the exterior of the mansion still looks a lot like it must have in 1905. Its brick arches and tall, skinny Victorian windows are just a little odd set against the neighboring Neoclassical and Craftsman houses — and yet the house is undeniably wonderful. It’s a building that catches the attention of passers-by, one of the rare private homes that most people in Houston just seem to know.

If only they all knew its whole story.

Jim Parsons is Director, Special Projects, with Preservation Houston. Parsons was one of four panelists at the Rice Design Alliance's inWARDS: Reflections on Houston's Wards civic forum on March 24. Below you can watch his talk on the origins of the wards.