This review is part of a special series about preservation in Houston, edited by Helen Bechtel, published in connection with two national conferences in Houston in November.

This week Houston serves as host city for two significant symposia on historic preservation: the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s annual conference, PastForward, and the Preserving Communities of Color conference, organized by the Historic Black Towns and Settlements Alliance. For the next five days, preservation professionals, stakeholders, and enthusiasts will gather to exchange ideas, tour preservation sites, and discuss the future of the field as they mark the 50th anniversary of the passing of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA). Houston’s unique history of urban development, which has now grown to support 22 historic districts reaching across the nation’s fourth-largest and most ethnically diverse city, makes it a welcome context in which the leaders of the field can strategize about the future of the preservation movement.

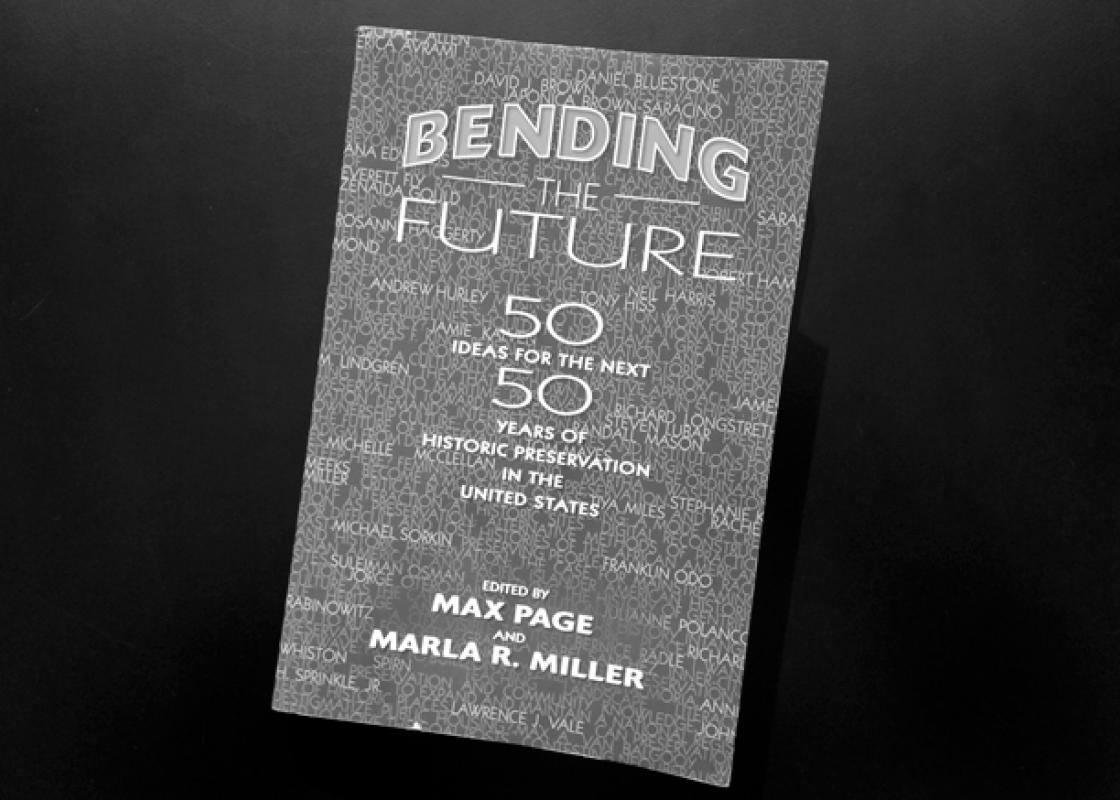

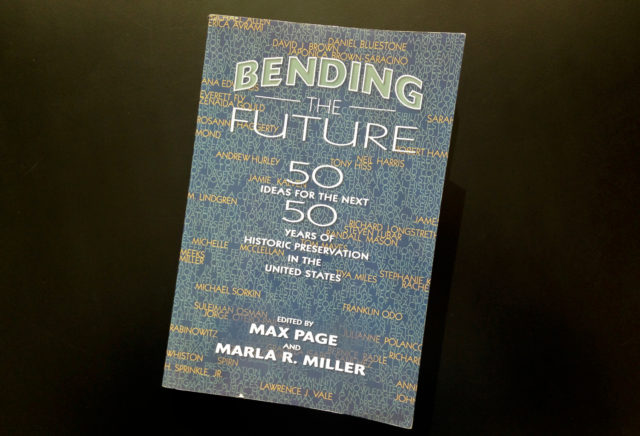

As our city prepares to host these exchanges, both seasoned and new preservationists alike could benefit from reading Bending the Future: 50 Ideas for the Next 50 Years of Historic Preservation and United States, an anthology edited by historians and preservationists Max Page and Marla L. Miller. Inspired by the occasion of the NHPA’s 50th anniversary, Page and Miller have assembled a comprehensive collection of essays --- or as the editors call them, “provocations” --- that collectively challenge the field’s status quo and make recommendations for the years ahead.

Articles range from specific case studies to general comments on the future of the field; participants include academics (the most represented), community activists, architects, and preservation professionals.

In their substantive introduction, the editors set an ambitious tone for the collection with the presentation of six fundamental questions to which the essayists collectively respond. These questions cut to the very core of the field’s identity and mission, signifying a great desire to use this moment as an opportunity to reconnect with grassroots energy and re-address the fundamental tenets of the preservation movement. The questions: “What is a preservationist?” “What should be preserved, and why?” “What stories should we be telling?” “How do we, and should we, tell the histories of significant places?” “Can preservation help create more economically vibrant and just communities?" “Can preservation help save the planet?”

With this big-picture list of considerations, Page and Miller offer up not only a loose preview of a new conception of the preservation movement, but also an indication of how vast and varied the field may soon become.

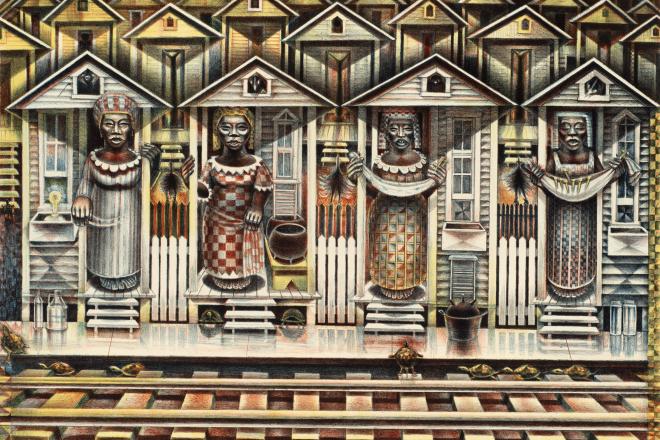

Though there are a handful of essays that offer multiple sides of a particular debate (for example, the role historic preservation has or does not have in gentrification, and what to do about the negative effects), on balance the essayists put forth a unified voice on a few fundamental points. Most, if not all, contributors feel strongly that the movement is due for a re-branding and reconsideration of its identity and perception. They argue that it should move away from the identity of the elitist academic who preserves only architectural landmarks that signify important moments in an overwhelmingly white and male interpretation of history. They passionately urge the field to make every effort to be more inclusive and diverse and to fight for more representation of the parallel histories of traditionally marginalized groups. They collectively lament the current policies that put forth the criteria for determining and governing historic sites, explaining how they are limiting, short-sited, and outdated. And they argue fervently for a greater emphasis on preserving and extending the life of all types of places that are sites of important events, instead of simply pursuing the static preservation of buildings.

All of these goals speak to the desire for the field to become more active, inclusive, and future-oriented, and for preservation to become a powerful tool that can also be used to aid related goals of economic vibrancy and social health in our communities. These are valiant goals, and I would predict this passion as a clear indicator of likely success if there were not a fundamental obstacle in the way, which many essayists acknowledge but no one seems to tackle head-on: how do we evaluate our relative success in achieving a series of new goals, when many of those goals are fundamentally emotional and cultural, and therefore largely unquantifiable by any common metric? After finishing the collection of essays, I was overwhelmed with how difficult it will continue to be to chart the intangible, particularly as the diversity of histories grows. Many authors push the need for “new tools” and “formal mechanisms” and “more inclusive policies” and “a holistic approach” --- but what would those actually look like?

It’s no wonder I found that the most compelling essays were those that are the most specific; you can almost feel the effort it took for each author to stay away from glittering generalities and instead put forth concrete suggestions for change. Some of the most interesting ideas came from essays like “Historic Preservation: Diversity in Practice and Stewardship” by Everett Fly, who offered specific ideas about new ways to educate and train preservation professionals, or “The Necessity of Interpretation” by Donna Graves, who presented concrete suggestions for how to expand, fund, and implement the ongoing interpretation of existing and new historic sites. These are just two examples of several essays that offered clear road maps for the field’s thoughtful advancement. Other compelling ideas ranged from illustrating innovative techniques for how to use digital technology to layer information, to suggesting new ways to structure property ownership in order to facilitate stewardship and future preservation.

I applaud Page and Miller for urging their colleagues to self-evaluate and take the time for introspection, and for collecting the results of that exercise in this anthology. As mindful as I was of the challenges ahead for preservation, I was inspired by the creativity and forward-thinking ideas expressed across the collection of essays. Here in Houston our preservation culture is young enough that, as we grow and solidify our preservation policies, we have an opportunity to debate and directly implement some of the book’s suggestions for how to be more inclusive, continuous, and future-oriented. Let’s get the most we can out of our role as hosts for these milestone conferences, and then let’s use that knowledge to lead the nation in the implementation of preservation’s most innovative and forward-thinking practices.