This essay, written by Rice School of Architecture Gus Sessions Wortham Professor of Architecture Albert Pope, first appeared in print in Cite 97: The Future Now. We will present the essay in two parts. The first examines the relationship between Houston's freeways and bayous.

Control and Accommodation

While we tend to regard cities as permanent and unchanging, they are constantly adapting and readapting their basic forms to their natural settings. Such adaptations have occurred since the beginning of urban history and usually take place, not over months or years, but over decades and centuries. The natural conditions that brought Houston into existence were an abundance of natural resources that put agricultural commodities (primarily cotton) in relative proximity to a protected port.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, it was the significant dredging of Buffalo Bayou that boosted Houston’s port functions and turned the city into the second-largest petrochemical complex in the world. Today Houston’s network of bayous places it at the nexus of the global carbon economy.

As urban and natural systems continue to evolve, climate scientists tell us that they will do so with increasing speed and volatility due to the extraordinary amount of CO2 that has been put into the atmosphere. Houston is threatened by this volatility in two distinct ways. The first threat concerns rising sea levels that will affect all coastal cities and put at risk the entire southeast quadrant of the city (including our petrochemical complex, which is situated only inches above sea level). The second and perhaps more significant threat concerns the extraordinarily high levels of per capita energy consumption in Houston (double that of European and Japanese cities). As the newest and most dispersed of all major American cities, Houston's infrastructure locks it into a high degree of energy consumption, which, in the long run, will damage the city's viability. As the dual threats of low-lying inundation and high per capita consumption have become increasingly clear, big changes will be upon us, changes that will require a significant renegotiation between the city and its natural context.

In its first 179 years of growth, Houston’s economy was built through the seemingly limitless exploitation of natural resources. Today, few of us believe that natural resources are unlimited, nor do we believe that their exploitation comes without cost. Where we once believed that natural forces could be fully controlled, we now recognize that control must give way to accommodation. The good news is that the outlines of that new recognition can already be seen in transformations that are taking place across the city. This essay will outline one of these transformations as it relates to the underlying structure of of Houston. Specifically, it will outline the city’s transition from a concentric-and-dispersed, car-oriented city into a linear-and-dense, transit-oriented city over the next half century. This transformation is being spurred by a remarkable new natural/urban network that has only recently been assembled: Bayou Greenways 2020.

Channels and Viaducts

In order to think through the city’s changing relations to its immediate natural environment, a certain distance needs to be maintained. While we might want to enter into an analysis at a local level of the environment, we need to keep a focus on the bigger picture. The interaction between urban and natural systems should not be overwhelmed by immediate details. Although those details determine our lived experience, it is important to step back and consider the large-scale, defining features of the city and its ecosystem. In the case of Houston, these defining features are its key urban transportation infrastructure and its extensive bayou network. In order to characterize the effects of these two networks, and the complex negotiations between them, it is necessary to examine the concentric, hub-and-spoke organization of the city’s freeways and the banded, linear organization of the city’s bayous.

This top-level organizational logic will be played off the photographic evidence of these systems as they actually hit the ground. The recent (2014) aerial photographs of Houston taken by Alex MacLean focus on specific overlaps of the freeway and bayou networks. The photographs systematically document both the congruences and the collisions of the two systems as the urban sometimes dominates and sometimes accommodates the natural conditions in which it exists. While the ostensible subject of the photographs might be superficially characterized as an ongoing battle between viaducts (freeways) and trenches (bayous), on second glance a far more intricate interrelation is revealed. These interrelations suggest an underlying shift from a narrative of domination or control of nature to a narrative that focuses on accommodation. More than any technical description, these photographs reveal an ongoing renegotiation between natural and urban systems in which the next century of Houston’s growth can already be glimpsed. Beautiful as they are, however, MacLean’s photographs cannot fully depict the fundamental reorganization that is occurring beneath their surface appearance. In order to more fully describe what is seen in the photographs, we must turn to the larger logic that frames them.

Beyond the Monocentric

In the first 179 years of its existence, Houston's centralized pattern of urban organization was superimposed upon the linear east-west logic of its natural organization. In other words, its symmetrical organization surrounding a single and dominant urban core had almost nothing to do with the predominantly asymmetrical east-west organization of Buffalo Bayou and its tributaries. Though common to most cities, the concentric pattern of freeways is also emblematic of Houston’s presumptive dominion over the natural systems that made the city possible in the first place.

Even today this presumptive dominion holds sway. In many quarters, it would still seem absurd to think that the hub-and-spoke logic of Houston’s transportation infrastructure could ever be challenged by the natural order of Houston’s bayous. Such presumption remains pretty much unchallenged until, of course, it starts to rain. It takes only one of our many flashfloods to understand that the linear network of bayous remains a potent if not dominant force upon the city as it wreaks havoc on the concentric system of freeways. It is indeed a measure of our presumptuousness that we rarely even consider that freeways could have been built around the logic of floodplains. Flooded-out freeways are largely due to their concentric arrangement that requires them to be randomly built in and out of floodplains. If freeway placement were to more fully consider the logic of the bayou network, instead of an arbitrary, centralized pattern, flooding could doubtlessly be diminished.

Rather than reconciling the opposing forces at a top or systems level, engineers attempted to transform natural systems into something resembling the network of freeways. In the name of water management, the city’s bayous were systematically transformed into a series of open storm sewers. As is rightfully lamented, vegetation was bulldozed, irregular topography was graded smooth, and a concrete surface was poured in order to transform the city’s riparian biota into a highly engineered artifact. Many of MacLean's most striking photographs reveal a perverse equivalence of the freeway suspended above the ground on concrete viaducts and the bayou sunk below the ground in concrete trenches. Whether managing vehicles or managing water, the idea was that everything could be channeled and controlled. In the meantime, it has become clear that armored channels are simply no match for the riverine system and the increasingly volatile climate of which it is an integral part. Each great storm unmasks an increasingly crippled infrastructure that is unable to recuperate from shocks to its system. In the meantime, the need for a systems-level approach, such as pulling construction out of the 100-year floodplain becomes ever more obvious.

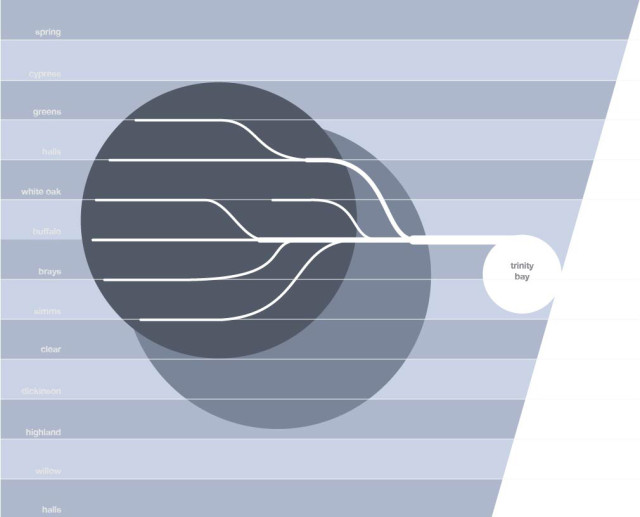

In contrast to the concentric organization of Houston's freeways, the bayou system is configured in a series of lines or bands that run east-west, from prairie to the coast.

In contrast to the concentric organization of Houston's freeways, the bayou system is configured in a series of lines or bands that run east-west, from prairie to the coast.If the failure of Houston’s concentric system of organization to respond to the region’s natural systems has become apparent, its failure to respond to contemporary urban forces are equally problematic if not more difficult to grasp. This failure is due to the simple fact that Houston has long outgrown its founding logic. Conceived as a monocentric city, Houston was imagined as growing from its single and dense center out to its edge. As the city grew, planners imagined that its core would also grow, maintaining its dominant position relative to the rest of the city. There is, however, a limit to which a single urban center can be expected to exert an influence upon a sprawling periphery. Covering an astonishing area of 650 square miles, Houston within its city limits can contain the cities of Orlando (101 square miles), Denver (155 square miles), Philadelphia (140 square miles), Las Vegas (112 square miles), and San Francisco (46 square miles) with room to spare. In spite of the fact that Houston can contain all six cities, it is important to note that each of them has an urban center equal to or larger than the center of Houston. In short, the “center” of Houston, with its relatively small number of city blocks and tall buildings, can no longer be expected to exert an influence over the vast expanse of its 650-square-mile hinterland. Despite the centralization of its most vital transportation network, Houston ceased being monocentric decades ago.

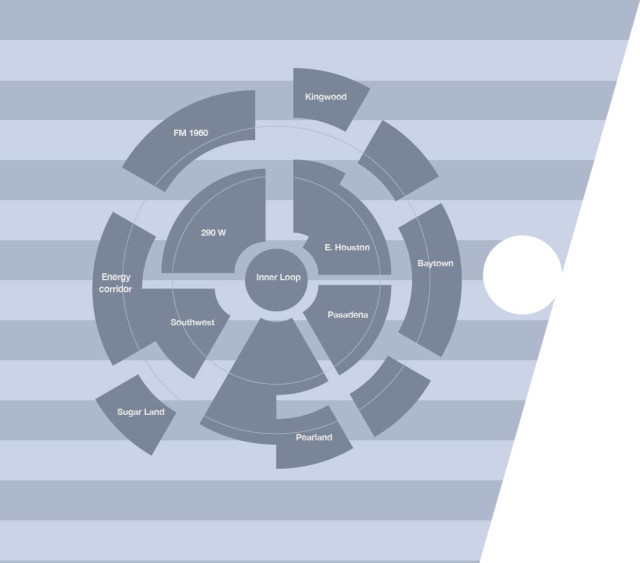

In order to organize its vast extent, multiple centers have emerged throughout the city with no particular allegiance to Downtown. The Energy Corridor, Southwest, 290 and FM 1960 corridors, Sugar Land, and Pearland are understood as slices of the concentric pie, yet they operate as autonomous units. In the place of its original concentric network formed by a single dominant center, Houston has developed as a far more robust polycentric network that is capable of structuring its extensive urban ground. Based on an ancient model of central/peripheral organization, Houston’s hub-and-spoke transportation system is not responsive to the polynuclear organization that exists today and will in the future. To put it simply, all roads lead to where only a relatively small number of people need to go. Given the city’s polynuclear organization, the obvious question to ask is what pattern of transportation would be more responsive to this model of distribution? If the existing system is designed to deliver traffic to a single, central point, what pattern would best deliver traffic to multiple points? One answer to this is an interlocking system of lines, not unlike the interlocking lines that make up the city’s network of bayous.