Photos courtesy Actar.

Before I had children, Houston was to me a city of writers, artists, and activists. The oil and gas industry was an abstraction. Once I started attending parent meetings and playdates, however, I came to know families with a father spending weeks away from home on a regular basis. They flew to some deep-sea platform or a rig in the middle of North Dakota. Given this local familiarity with the human struggle behind every gallon of gas, it is appropriate that the proposals in a new book called The Petropolis of Tomorrow (Actar Publishers 2014), co-edited by Neeraj Bhatia and Mary Casper, were partly developed here in Houston and that the book will be launched on March 17 at the Rice School of Architecture.

One of the three proposals in the book won the Odebrecht Award for Sustainable Development. A team of Rice students led by Bhatia designed an audacious water-based urbanism, a new kind of human settlement around oil extraction. In issue 91 of Cite, Ana María Durán Calisto considered this award-winning proposal in the article "Expanded Architecture." Here's an excerpt:

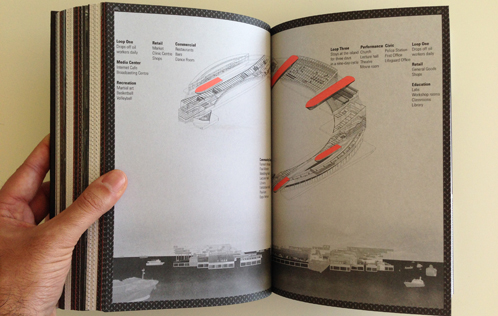

They see an opportunity in the veritable archipelagos of oil rigs being built in the water. In Drift & Drive, the Rice team conjures a massive new inhabitable territory: a dynamic, urban, artificial archipelago where industry coexists with schools, libraries, hospitals, houses, novel and well-organized transportation networks, waste management, and agricultural fields (not monocultural, but hybrid and rotational). The idea of settlement has returned. What had become a mere extraction enclave of minimum provision for human needs is being rethought in terms of inhabitation. This process calls for the reinvolvement of the architect. Drift & Drive should not be dismissed as an outlandish academic exercise. Rather, it is an excellent example of a renewed dialogue between industry and design.

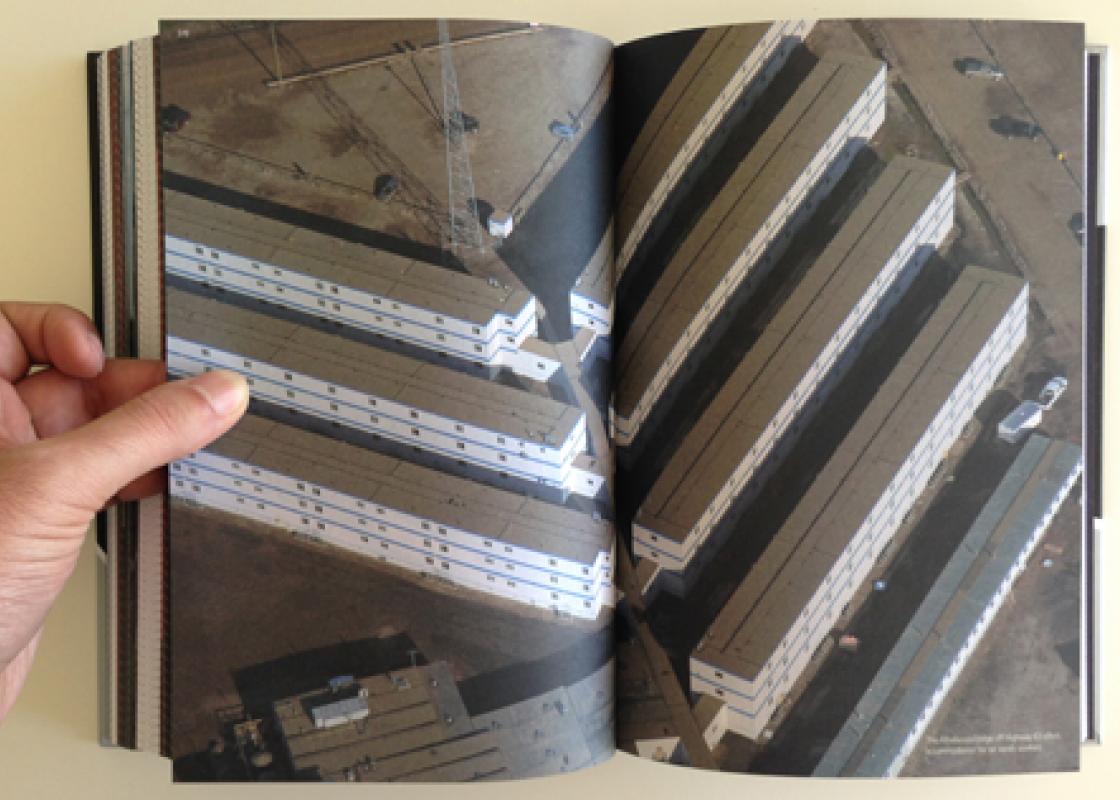

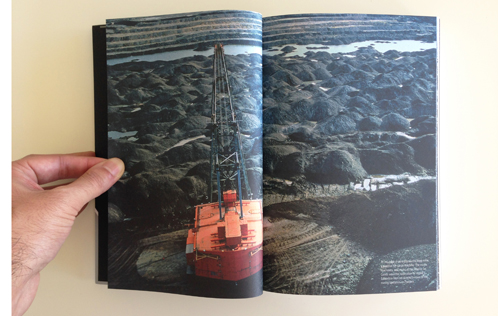

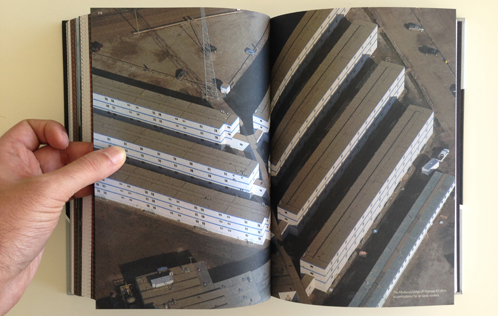

If The Petropolis of Tomorrow unpacked only this proposal, it would be notable enough, but the weighty book includes far more. The first section, called Observations, features photoessays by Garth Lanz, Alex Webb, and Peter Mettler. Many of the images show the vast scale of the Alberta Tar Sands in Canada. I am too inured to such images to pause when I see them. On a nearly daily basis, I receive alarming emails and online petitions with dystopic photographs of wells and mines meant to jolt me into clicking the "Sign" and "Donate" buttons. The photographs in the book are scary to be sure, but they are carefully framed to do more than provoke a knee-jerk reaction. The images of living quarters, in particular, slow you down. You flip past the numbing endlessness of the open-pit mining to be confronted with the stark narrow confines of the workers' housing, sometimes called "man camps."

The rest of the book weaves together critical essays and the three design proposals. The essays are by well-respected architects and scholars like Luis Callejas, who has taught at Harvard, lectured in Houston, and designed gorgeous public pools in Columbia. The critical essays and design proposals are organized along three themes: Archipelago Urbanism, Harvesting Urbanism, and Logistical Urbanism. I was caught off guard by the last theme in a good way. "On-Demand Urbanism: Learning from Amazon.com," by Clare Lyster, doesn't discuss oil extraction. As the title suggests, the piece ponders what the world will be like once more of our built environment catches up to the fact that almost anything you want can be delivered directly to you. (She suggests houses will be designed with refrigerated delivery receptacles.) So the book is of greater relevance than the title suggests. Oil extraction is the focus of an attempt to update or re-orient the approach of the architecture discipline.

When Bhatia taught at Rice, we both attended a lecture by Stanley Tigerman, who railed against what he considers the complicity of architecture schools in a fundamentally exploitative capitalist system: students are trained to be cogs in a speculative machine. What stands out about The Petropolis of Tomorrow is that it refuses a black-and-white way of looking at the world where design is either defiant or complicit.

I've seen one too many environmentalist speakers come through Houston and lecture us about how profligate and ruinous our industry is only to fly off in a plane burning jet fuel. The Petropolis of Tomorrow is more radical than those easy diatribes. It is by turns a horrifying and inspiring set of visions. I hope some of my neighbors in the industry read the book while hunkering down in a man camp. Though, like many architectural publications, this book can be overwhelmingly visual, and the architects make endless references that only other architects will understand, the content is provocative enough to engage all kinds of people. (You can buy it on Amazon, no refrigerated receptacle required.)