In 1917, a young Georgia O’Keeffe would watercolor the Texas sky, the first evening star at dusk, over and over, transfixed. The elegant lone star of the Lone Star State reminds us of independence, strength of vision, solitary righteousness, the power of one. Utah’s nickname is the Beehive State. Utahns aren’t insulted to be bees. We know we have to work together to share a vision. We needed a hive, not thousands of honeycombs. What could a lone star learn from a honey bee?

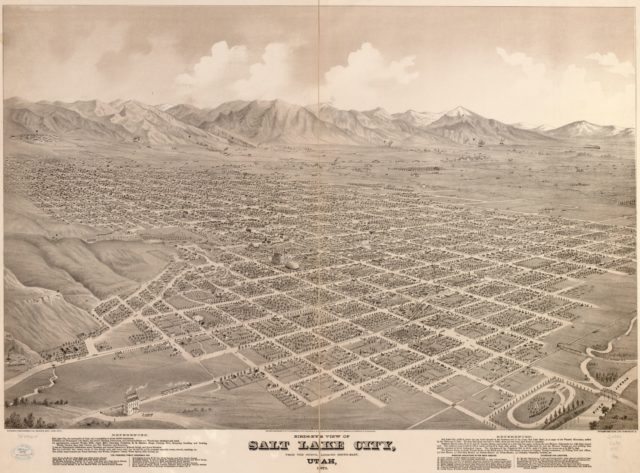

Birds-eye view of Salt Lake City, Utah 1875. Source: Library of Congress.

Birds-eye view of Salt Lake City, Utah 1875. Source: Library of Congress.It’s Texas lore that planning curtails growth, or that land-use regulations stifle the economy. This contradicts my experience of what urban planning does to a city. Growing up in Utah, I observed that urban planning bolsters economic growth, decreases pollution, and fosters pride of place. Though one is in the Rockies and the other on coastal prairie, the similarities between Houston and Salt Lake allow for relevant comparisons regarding urban planning and, specifically, public transportation. Both Houston and Salt Lake are located in red states, with strong religious underpinnings and severe pollution problems. While the Salt Lake region welcomes urban planning, Houston’s potential is stunted by the absence of essential features like sidewalks and public transportation. What can we learn from the Utahns? Let’s start at the beginning.

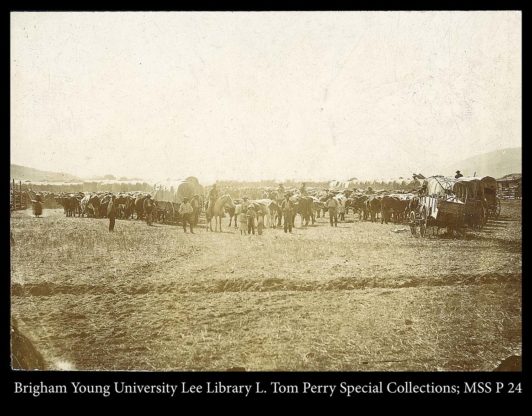

Pioneers and covered wagons. Written on the back- C.R. Savage Print

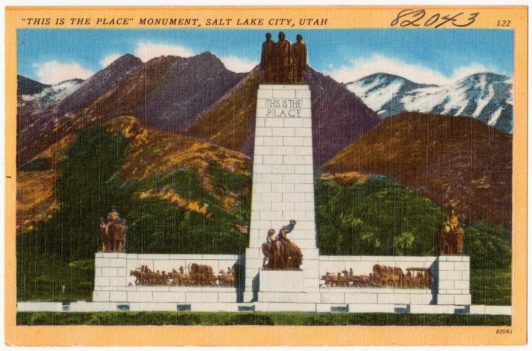

Pioneers and covered wagons. Written on the back- C.R. Savage PrintThe Mormon pioneers were radical. They weren’t known for pressed pants, minivans, big smiles, and conservative hairdos back in the 1800s. For the locals Mormons tried to live next to, they were perceived more as a Branch Davidian type of situation. Dislocation peppers early Mormon history. Desperate for a home, a band of scouts forged the Mormon Trail. In summer of 1847 the wagons stopped and Mormons saw Utah for the first time. Brigham Young, the prophet of this motley crew, locked eyes on the vast Salt Lake, with enormous mountains on all sides, and said, “This is the place.” Instead of hearing about Sam Houston or the Alamo, as Texas kids do, or about the Allen family as Houstonians do, I was given Mormon pioneer stories. One pioneer family had no choice but to heave their piano off a mountainside. The piano was too heavy for the wagon to endure once they’d hit a mountain range, even though they had pulled it for hundreds of miles already. I pictured the piano barreling down the ravine, keys cascading, strings snapping, dissonant end of life chords bathing the canyon in sound, and the heartbroken soul who had hoped to play it, and who had helped to pull it this far, watching on.

"Route of the Mormon pioneers from Nauvoo to Great Salt Lake, Feb'y 1846-July 1847," map, printed by Millroy & Hayes

"Route of the Mormon pioneers from Nauvoo to Great Salt Lake, Feb'y 1846-July 1847," map, printed by Millroy & HayesLike Texas, this would be no mere state. Deseret, a term from The Book of Mormon and Utah’s first name, was a rogue entity. Old maps expose the pioneers’ dreams and show Deseret scrawled over half of the United States, larger than Texas. We had our own language, The Deseret Alphabet, and our own money too.Once in Deseret, my ancestors designed and built Salt Lake City. To this day, Mormons sit around and brag to each other about how smart the pioneers were when they developed a simple street grid with large blocks and wide streets that was expanded over time and continues to define the city, and many see our beautiful city as proof of divine intervention.

Washington Monument Deseret Stone in 2000, donated by the Utah Territory, Sept. 1853

Washington Monument Deseret Stone in 2000, donated by the Utah Territory, Sept. 1853In this sense, our urban planning is holy to us. As a fifth-generation Mormon, all this history and pride was carved into me. In adulthood, I chose to let go of the doctrinal beliefs but not of anything else. My mother would always say, “Don’t forget who you are.” I could not forget my roots, but, as it turned out, I also couldn’t stay in Deseret. My career field was oversaturated. Applying for tenure-track positions was like a game of roulette. After years of rejected applications, I was offered a full-time teaching gig at San Jacinto College, North Campus in Houston, and I accepted. Being a college professor was all I wanted to be, and Houston was the only place I could do that.

I knew nothing about Houston. While apartment hunting, locals told me to stay in the loop. Go to Clear Lake, The Woodlands, and my favorite, Sugar Land, they said. Some even spoke of staying inside of an inner loop. No one suggested that I live where I worked, on the east side of Houston. Befuddled, I perused a city map.

Upper Kirby. Photo: Monica Yancey.

Upper Kirby. Photo: Monica Yancey.

Two circular freeways surrounded downtown; one was smaller than the other with the city center at the target spot. Therefore, in Houston, you can be outside of the Beltway 8, outside Loop 610, or, finally, inside Loop 610 or “in the Inner Loop.” The magical sounding names, Sugar Land, were suburbs. I still didn’t know what any of this connoted nor did I know what the trouble with the east side was.

I found a place inside the Inner Loop. But my apartment, in the Upper Kirby neighborhood, overlooked an expanse of asphalt. After a while, it felt like I was sleeping in a parking lot. Still, people kept telling me I was in one of best areas. I fled Upper Kirby in search of a better neighborhood and discovered Goose Creek, a subdivision adjacent to Baytown’s city center. A tiny bungalow was for rent, and it had a peaceful, shaded, parking-lot-free porch. I noted my coworkers’ veiled repulsion at the mention of Baytown, a city East of Houston, but proceeded with the move. I didn’t trust locals to give neighborhood advice anymore.

Goose Creek bungalow. Photo: Monica Yancey.

Goose Creek bungalow. Photo: Monica Yancey.

Once settled, my husband and I decided to walk to an ice cream shop about a half mile away. To our shock, the route was missing sidewalks. With no area for walking, we had no choice but to hobble over private lawns. We forged ahead over broken fences and glass, glancing up to make sure we weren’t offending homeowners. The street lacked a shoulder too, so we had speeding traffic inches away from our bodies. With my heart racing, fight-or-flight response in full swing, I processed my surroundings. The only other people I saw were men on bicycles, narrowly avoiding the cars, with grocery sacks swinging from handlebars. I feared for their safety. Cars, trucks, and diesels zoomed, over the speed limit, up and down the streets. The constant boom of mufflers backfiring created the soundscape of war. It was terrifying. Once we got there, we pretended to enjoy the ice cream, easing the tension like joking at a funeral, but we never walked for ice cream again.

Much of Baytown lacks sidewalks. Photo: Monica Yancey.

Much of Baytown lacks sidewalks. Photo: Monica Yancey.

I soon discovered that in most of Baytown, there weren’t sidewalks at all. The ones we did have stopped and started at random, forcing pedestrians to bob in and out of traffic. These periodic sidewalks were bungled up by roots or puddles, and it was clear that no budget line item read sidewalk repair. In conversation, I found myself advocating for the sidewalk to anyone who would listen. I knew it sounded dull, like being a passionate aficionado of plywood, but when you can’t go for a walk, your world shrinks. Where was this Texas pride of place I had heard so much about?

Adding insult to injury, I had hoped to bus from Baytown to the college where I teach, but there wasn’t a route. An inspection revealed that my college, which serves nearly 10,000 students, does not have a single bus stop. This means that my students have to spend most of their entry-level incomes funding a private commute. Those without cars would have to drop out of school, beg others for rides, uber or risk their lives attempting to be pedestrians in a city without sidewalks. Clearly, in the absence of public transportation, we would all be driving to school. And to get there, from Baytown, I’d be going through one of the largest oil refineries in the world.

I’ll never forget my first commute. Toxic smells wafted into my car as I drove on an elevated bridge high enough up to see the miles and miles and miles of refinery. Panicked by the sight and scent of it, I turned my A/C unit to interior air, a delusional gesture aimed at protecting myself and my niece, who rode to school with me, from carcinogenic pollutants.

Commute to work. Photo: Monica Yancey.

Commute to work. Photo: Monica Yancey.Engulfed by this vista, I had the sick awakening that Upper Kirby was nice relative to other parts of Houston. When people told me to stay in the Loop, it was a warning. I had moved into the belly of the beast. This was why people winced when I said I was moving to Baytown. Houston’s warm climate and rampant pollution create a hotbed of smog, especially on the east side. My beloved porch turned out to have the same nerve-wracking smells, but I had no button to push.

When my lease ended, I fled to the west side, to the Heights – an expensive but walkable neighborhood in Houston, far from the smells. I was now in the Loop. But I remembered my neighbor from Goose Creek. Our mutual language barrier kept us from being close, but my grandmother’s death shattered our silence. Reading from my phone, I spoke the words that Google Translate gave me in my clumsy English accent, “Mí abuela murió. Soy de Utah. Yo no soy de aquí. Tengo que ir a su funeral. ¿Puedes mirar mi casa? Lamento preguntar, pero no tengo a nadie más para preguntar.” Four generations lived in her house; I knew she would understand. She put her hand on my shoulder and said, “Yes, yes, yes.” She is still out there, breathing that air. So are my students. On the East side, they are, in all senses, outside of the loop.

According to Bill Fulton, the Director of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research at Rice University, “Of the major U.S. cities that have planned at a regional level, Salt Lake City is one that Houstonians would do well to study.” He notes that “the two regions share the political challenges of a deep red state, mixed counties, and blue cities. They also both have largely post-World War II built environments and young populations that rely on private automobiles. Nonetheless, Salt Lake City has managed to work with the state and across county jurisdictions on a range of issues including mass transit.”

The decision by lawmakers to pursue improved transit was enabled by The Coalition for Utah’s Future’ public engagement project called Envision Utah. Peter Calthorpe and William Fulton document the process in their book The Regional City (Island Press, 2001). Calthorpe and Fulton write, “When average citizens are allowed to understand the aggregate effects of differing forms of development, they have a dramatically different reaction to the politics of growth than when confronting it project by project. Seeing the whole allows people to make different judgments about local development. And their participation in the geology of uncovering their own future is a powerful experience.”

Envision Utah published actual design plans (and their associated costs) in newspapers with mail-back surveys that asked Utahns to assess different development scenarios.

Calthorpe and Fulton describe an urban planning process that integrates the locals: “A series of hands-on public workshops (entitled Where Shall We Grow and How Shall We Grow) were organized to encourage people to participate in a direct way in solving their unique problems of growth.” In contrast to the development types that are so popular today, workshops attendees overwhelmingly preferred walkable environments such as “porch front homes rather than garage fronts, main-street retail areas rather than strips.” In other words, even though we’ve fled from these basics over the years, people still want real neighborhoods. The notion that Houstonians cannot embrace urban planning is likely false. Empowering Houstonians to dream about what’s possible for our city will yield great ideas, hope, and optimism.

Envision Utah also conducted a study to ascertain regional values. They then used Utahns’ values to make development choices. They were able to show people how supporting community planning measures would actually allow them to live their values more fully. For example, one value that Envision Utah honed in on was personal time. They were able to convince Utahns, rightly, that the time loss they were experiencing due to traffic congestion could be solved and therefore that urban planning promoted a value they held dear. I teach this tactic to my first-year public speaking students. It’s persuasion theory 101, and it works. Tailoring your proposal to the values of your audience is highly persuasive. And, as I say in class, it’s ethical as long as what you are promoting fosters the public good.

What Houstonian values might we consider as we lead our city to a brighter future?

Salt Lake City sidewalk crossing flag. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Salt Lake City sidewalk crossing flag. Source: Wikimedia Commons.Of course, Envision Utah couldn’t talk to everybody. So when the trains entered our world, most residents had no idea what was coming. Thankfully, marketing and public service announcements oriented us to our new reality. Pedestrians and motorists alike had to learn to navigate the addition of trains to our city streets. Trains produce an increase in pedestrians making sidewalks and crosswalks an integral part of train safety. In Salt Lake City, unlike Baytown, sidewalks are mandatory parts of the construction process, so most areas were already safe for walkers. Still, at new crosswalks, the city provided fluorescent flags attached to wooden poles, to carry in our hands and wave at cars. I recall that I felt silly carrying the flag and waved it like it was a joke, but cars stopped. Avoiding collisions was a paramount concern. Police designed traffic rules and ticketed us into compliance. We adapted with the help of safety campaigns.

To the city planners’ relief, when residents experienced firsthand how fantastic light rail trains are, it wound up being a no-brainer. Trains were clean, fast, and cost-effective. In practice, there wasn’t any reason to shun them. The light rail system drastically reduced commuting stress. Students, lawyers, window washers and school children sat together each morning and night. It cost $100 a month for unlimited use, and when I was a student, it was free. Not having to front the costs associated with a private commute made young adulthood manageable.

When ballot measures sprang up to extend lines, voters approved. Train stops became economic and residential hubs almost overnight. Businesses thrived, communities flourished. Real estate ads bragged about their proximity to train stops. The trains now span the length of the valley, nearly one hundred miles! Our city transformed and the populace changed their view just as rapidly. You’d be hard-pressed to find a Utahn, of any religious or political persuasion, who isn’t proud of our public transportation infrastructure and who doesn’t (at least occasionally) use it. In fact, we think it is yet another example how wonderful Salt Lake City is. In a matter of fifteen years, we became a model of urban planning. What could Houston be in fifteen years?

Public transit benefited us economically, but crucially, it was saving us from a devastating problem. The same mountains that inspired Brigham Young’s prophetic declaration (“This is the place!”) hold pollution in the Salt Lake Valley, like a bowl, and saddle our region with the unflattering distinction of being one of the most polluted cities in the United States. In Salt Lake, vehicles are the leading pollutant; scaling up public transportation is part of a long-term solution. None of this is theoretical to my mother whose respiration is sensitive to pollution. She obeys inversion warnings in the forecasts by staying indoors. She’s a politically active Republican, and she was thrilled by the sophisticated trains. As far as she could see, anything that put less dirty air into our valley served us well; there was nothing partisan about it, in fact, it was the only choice. “What future does a city have if people have to wear masks to live in it?” she told me.

Old Postcard of"This is the place" Monument, Salt Lake City, Utah

Old Postcard of"This is the place" Monument, Salt Lake City, Utah

***

Houston’s colorful birds, tropical plants, and blooming Magnolia trees enliven our neighborhoods. We have parks and bayous, and alligators. We have a city worth living in, a city worth protecting. A flourishing economy, new bicycle paths, a vibrant arts scene, pride-worthy history, and enriching cultural diversity, poise Houston as a great American city. It’s evident that city planners are hard at work converting old thinking into a new more human-friendly city. But they need support. It’s important to remember that in the early days of Envision Utah, their fears echo ours. Calthorpe and Fulton write, “When they started, few believed a region so conservative and so committed to low-density development could change. But it has.”

Hondurans, Asians, New Yorkers, Europeans, New Orleanians, Salvadorans, Nigerians, and Utahns – we threw our pianos off cliffs to be here. In many ways, we had no choice but to come here. And it wasn’t easy, but we came, and we hope our gains will outshine our losses. We want to make this house a home. We are rooting for Houston. Attracted to the independent spirit of Texas, we’re ready to come together to create a shared city.