The last time Houston made a bike plan was 1993. Many of the streets declared official bike routes then are among the least safe places to bicycle. Take Washington Avenue. Every few hundred feet, a yellow sign with an image of a bicycle declares “Share the Road.” The street, however, has no dedicated bicycle path — not even a narrow one. Cars race down the 12-foot-wide lanes feebly painted with ineffectual “sharrows” that have faded from the friction of tires. Only “strong and fearless” cyclists, who represent less than one percent of the total population, attempt such routes.

The signage on Washington is visual clutter, or worse. It sends the wrong message to potential cyclists, according to Geoff Carleton of Traffic Engineers. If the city designates a route for bicycling, he says, it should be comfortable enough for “enthused and confident” riders, not just the spandex-clad racers in pelotons. Ultimately, says Carleton, a city’s bike facilities fail unless they can reassure the largest segment, as much as 65 percent of the total population, of potential cyclists: those who self-identify as “interested but concerned.” (The other group is the “no-way no-hows.”)

The Houston Bike Plan, a new draft released by the City of Houston, details just such a future. Made public and presented to the Planning Commission, the plan was crafted by Traffic Engineers, Morris Architects, and Asakura Robinson, a team comprising most of the designers behind METRO’s New Bus Network, a dramatic reimagining and restructuring that’s receiving national attention for its success. A grant to BikeHouston from the Houston Endowment provided part of the $400,000 budget for the new plan with additional funds coming from the City, Houston-Galveston Area Council, and the Houston Parks Board.

The process involved extensive community outreach across class, race, gender, and ethnicity, as well as a study of all existing plans made by the city, management districts, parks, livable center studies, and neighborhood groups. The resulting draft is more a fresh start than an elaboration of the 1993 precedent.

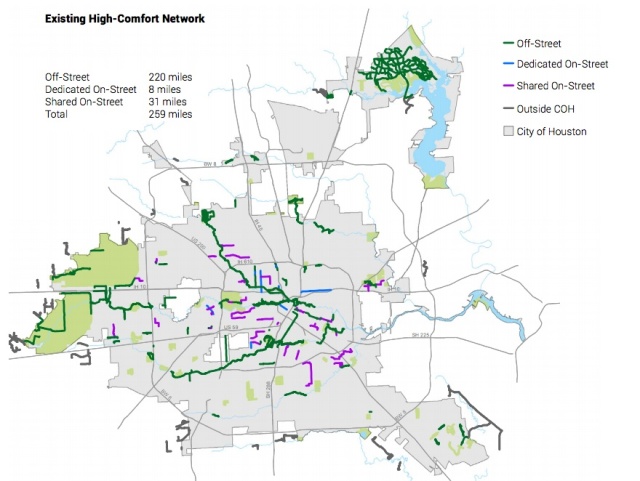

The plan begins with an assessment of where we are today and makes distinctions between high- and low-comfort bike lanes. Only the high-comfort routes are kept in the plan moving forward.

As the plan’s introduction states, Houston has “made great strides in improving people’s ability to bike to more destinations.” The plan also notes changes in attitude and ridership levels, calls out "Sunday Streets ... a great example of encouraging more people to get out and be active on Houston streets.” The most substantial improvement comes by way of Bayou Greenways 2020, the 150 miles of separated trails and linear parks along the bayous. (See our coverage of the 2012 bond measure funding this project, the progress of its construction, and the transformative impact it could have on our region.)

Approximately 1.3 million people --- six out of 10 Houstonians --- will live within 1.5 miles of these bayou trails when they are completed, but traversing those 1.5 miles can be a major challenge. When you map out this and other projects in the works, you see islands of bicycle-friendly territory and fragments of high-comfort bicycling facilities. Because the bayous run east-west, a lack of north-south routes could leave cyclists alone to contend with dangerous traffic and car-oriented infrastructure.

Example of incomplete connection to Bayou Greenways at Cullen Boulevard and Brays Bayou trail. Photo: Allyn West.

Example of incomplete connection to Bayou Greenways at Cullen Boulevard and Brays Bayou trail. Photo: Allyn West.

“If we do nothing beyond what is already in progress, we will have 300 miles of bikeways,” says Carleton, “but it won’t be a network.” Thus, the draft plan focuses on links that would build that network.

Ultimately, the vision is for Houston to become by 2026 a Gold Level Bicycle Friendly City according to the standards of the League of American Bicyclists. Currently, the city is Bronze Level.

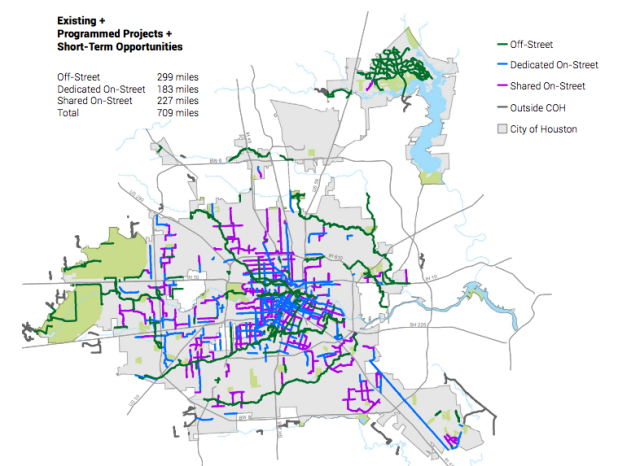

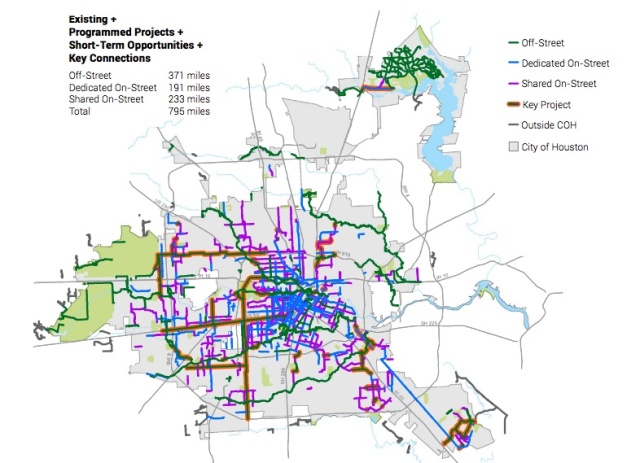

Here, the plan is broken down into three phases: 1) Short-Term Opportunities, which could solve problems quickly and relatively inexpensively; 2) Key Connections, which are high-impact improvements that would require more investment; 3) Long-Term Houston Bikeway Visions, which are true transformations of infrastructure that would require substantial investments of money, time, and labor. Below, we look at each stage as a whole and at few routes in particular as examples.

Short-Term Opportunities

In the last Kinder Institute Houston Area Survey, more than a quarter of respondents rated traffic as their biggest concern. We all experience the traffic jams. The traffic, however, is not a uniform problem evenly distributed across the city. We have more miles of roadway per person than any other major city. And some of those roads have excess capacity. On those roads, car counts are low and the lanes are wide. And in those cases, we can both accommodate cars and add high-quality bike facilities for the cost of paint and labor.

For example, by restriping and resurfacing Polk Street and bolting down a few “armadillo” bumps, the bicycle-friendly neighborhood streets of the East End can be connected to Downtown and the existing dedicated cycle-track on Lamar Street. With a few other small tweaks to that Lamar track, you could ride from EaDo in ease past Discovery Green and the Central Library through Sam Houston Park and into Buffalo Bayou Park with all its new facilities and trails and reach Shepherd Drive.

“Polk Street is a layup,” says Carleton.

Another major short-term opportunity, one that bicycle advocates have salivated over for years, is Waugh Drive. (Waugh is one of those crucial north-south routes that, sadly, has proved deadly to cyclists, as Chelsea Norman was struck and killed here in 2013.) A dedicated lane from Fairview in Montrose over Buffalo Bayou, through the Washington Avenue area, and under I-10 would stitch together the bicycle-friendly neighborhoods of Montrose and the Heights. Here, the changes would require more than paint for restriping. Rebuilding the on and off ramps at Memorial Drive to make the angles sharper would be an expense, but not a monumental one, and it would have a dramatic effect on the speed of traffic.

Currently, the trails on Buffalo Bayou are more or less a recreational loop. With links to and from Waugh and Lamar/Polk, Buffalo Bayou would become a major node of the network.

West Dallas into Downtown and Austin-Caroline between Midtown and Downtown are among the other short-term opportunities. The estimated cost for all these projects in the draft plan is $22-$45 million, and they would expand our high-quality bikeways by an additional 250 miles.

Key Connections

Horses graze, wild parrots fly, and organic farms grow along vast utility corridors that run through many bustling Houston neighborhoods. A recent change in Texas state law enables Houston to work with CenterPoint and other landholders to build trails along these rights of way that are as ubiquitous as they are unnoticed.

One such corridor is parallel to Westpark. Presently, it crosses Southampton/Boulevard Oaks, Rice Village, West University, Gulfton, the “Gandhi District” of Hillcroft, and Sharpstown. Each of these areas have islands of bicycle-friendly streets, but making it across such a long swath today is difficult — and, in the case of a man commuting to work January 25, deadly. Still, you can see “desire lines” in the grass where pedestrians and cyclists have already made use of the utility corridor. Formalizing that, and reimagining it as part of a high-comfort side path along Westpark, would provide an additional mobility option to a broad cross-section of Houstonians. Gulfton is the most densely populated neighborhood in Houston and home to many immigrants who don’t have access to cars.

Another such connection is the Spring Branch Utility Corridor, which would link the existing trails at Addicks Reservoir to the White Oak Bayou trail. The challenge is crossing 290. But doing so would provide an incredible link all the way from the Energy Corridor to the Heights.

Parallel to Stella Link is the north-south corridor from Sims to Brays to Buffalo Bayou through Memorial Park where the aforementioned horses, parrots, and farms are. Another extraordinary link.

Other key connections are smaller in scope but similar in their impact as links between islands. We are intrigued by a short connection under 610 to Holmes Road. This short, relatively inexpensive project would provide access from a low-income, African-American neighborhood to the massive job center that is the Texas Medical Center.

According to the draft plan, $66-110 million for the key connections would add 90 miles of bikeway and provide links to 80 percent of the population and jobs.

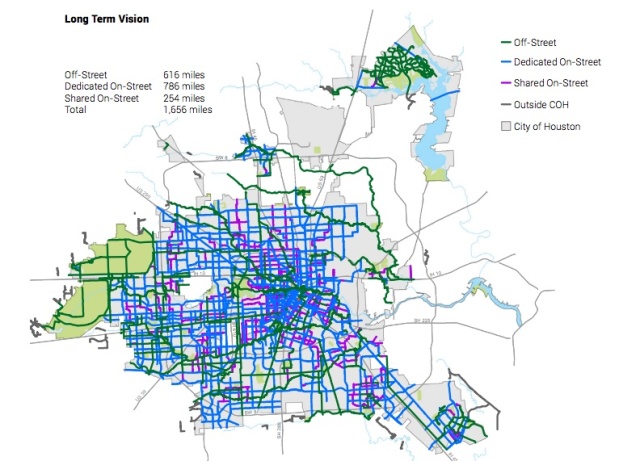

Longterm Houston Bikeway Vision

Let us recall the 2002 Buffalo Bayou Master Plan. At the time, it seemed absurdly ambitious and expensive. And yet extraordinary changes have happened, built up over time, in steps small and epic. The piecemeal progress yielded not a piecemeal thing but a cohesive landscape, because the master plan was in place. In fact, the pieces are still coming together, as Buffalo Bayou Partnership continues adding amenities like new pedestrian bridges east of Downtown toward the eventual terminus of the trail at Hidalgo Park.

So, when we look at a long-term vision, we must think in terms that are appropriate for the future of the city. We must ask not only what kind of city we want to be in 15, 20, or 25 years, but what kinds of changes will have visited all cities by then? We must be visionary. As Rebuild Houston unfolds, the draft plan could guide where the most substantial investments in high-comfort bikeways are made.

If the draft plan map were made real over a number of years, a high proportion if not a majority of Houston’s growing population could commute, shop, and visit friends by foot or bicycle. The cost for the 200+ miles of off-street trails is projected at $214-347 million. The cost of an additional 800+ miles of bikeways would be included in street reconstruction projects. The total cost of all phases comes in at $306-$502 million with a total network of 1,656 miles. To put that in context, Houston has about 8,000 miles of roads. To put that in more context, in 2014 alone, roughly $3.5 billion was spent on mobility in this region by the city, the Texas Department of Transportation, Houston-Galveston Area Council, METRO, and Harris County. The proposed multi-year transformation of bicycle infrastructure is a steal by comparison.

We have both used bicycles as our primary mode transportation at various times. We have been able to enjoy the high-comfort of the Brays Bayou hike and bike trail and the paths at Hermann Park as well as flinch and fear the high-stress of the shared lanes on Waugh and Washington. Seeing plans like these gives rise to a mix emotions. Elation for the ambition and the potential of the plan. Relief that our experiences are named, that the terrifying stretches of road that ruin an otherwise beautiful, cost-effective, energy-efficient, environmentally sound experience are recognized. Sadness and grief for those who have died or been maimed at many of the spots where interventions are planned. We also struggle with cynicism that, even if this plan is adopted, it will not be implemented. And we worry that Houstonians will react with a mindset of scarcity, believing that a better bicycle network means less space for those in cars, or believing that paying for these infrastructural improvements and investments in mobility means less money for other ones.

The draft plan is not only a series of lines on a map. It includes policy recommendations and education programs. For the city to become a safe place for bicyclists, for the city to become one where the “interested and concerned” of the population not only begin to imagine themselves on a bicycle but feel free to use the city with the power of their own legs, for the city to continue to attract those who are less and less interested in owning cars, both the forms of our streets and the norms of our behaviors need to change. And that will take messiness and dialogue. This is the beginning.

Additional reporting for this post was provided by Allyn West.