This article by Jack Murphy is part of a series on flood management in advance of RDA's H20uston architecture tour, March 25 and 26. Follow our publications and events about living in the floodplain at #H2Ouston and #SyntheticNature.

Austin is setting a new standard for flood management as urban design, and Houston would do well to study what's happening there. Waller Creek Park, developed by the Waller Creek Conservancy (WCC) and designed by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates (MVVA), will revitalize 1.5 miles of the creek between 15th Street and Lady Bird Lake at an estimated cost of $220 million. While Houston faces heavier rainfalls in a flatter and more flood-prone landscape, and while Buffalo Bayou and the entire Bayou Greenways system have rightly garnered national attention for Houston, the way the Waller Creek project reshapes Austin's rapidly densifying center offers important lessons about taking a comprehensive approach to parks, flooding, streets, and buildings.

In his 2017 State of the City Address delivered in late January, Austin Mayor Steve Adler opened with remarks about the enduring "weird" character of this place. Adler outlined his belief that we are “uncommonly good at changing in a way that renews our unique character” — that, through transformation, civic values are expressed and reaffirmed. In his address, Adler also noted “the future Waller Creek linear park may someday be the best-known manmade element of this entire city.” If the design is realized as proposed, he won't be far off.

Upper stretch of Waller Creek along Airport Boulevard. Austin's only light rail line, the Red Line, runs on these railroad tracks. Photo: Leonid Furmansky

Upper stretch of Waller Creek along Airport Boulevard. Austin's only light rail line, the Red Line, runs on these railroad tracks. Photo: Leonid Furmansky

Austin is a city on a river-turned-lake, but its urbanity is perhaps shaped more powerfully by its creeks, whose north-south flows contoured the area into a undulating east-west landscape of hills and vales. These waters collect run-off and accumulate sediments, but they also concentrate capital: proximity to creeks can mean both exclusive real estate in western and southern neighborhoods, or, downtown, blighted tracts ripe for development. Creeks can be dangerous — flash flooding is a serious concern, with disasters as recent as Memorial Day 2015 that put parts of the city underwater and claimed lives — or soulful: Barton Creek and Springs comprise an essential open space in the city, a greenbelt preserved in the 1990s after proposals for development threatened its watershed.

Waller Creek is an important waterway in Austin. It begins in the north, running along Airport Boulevard before winding through backyards in Hyde Park. It threads through the central campus of the University of Texas at Austin, in the shadow of the football stadium. It divides the new Dell Medical campus that opened last Fall. It snakes below Downtown, influencing buildings — the Hilton Garden Inn straddles a channelized portion, the southeast corner of the Austin Convention Center is a crenulated response to the creek breaking the street grid—before joining the lake.

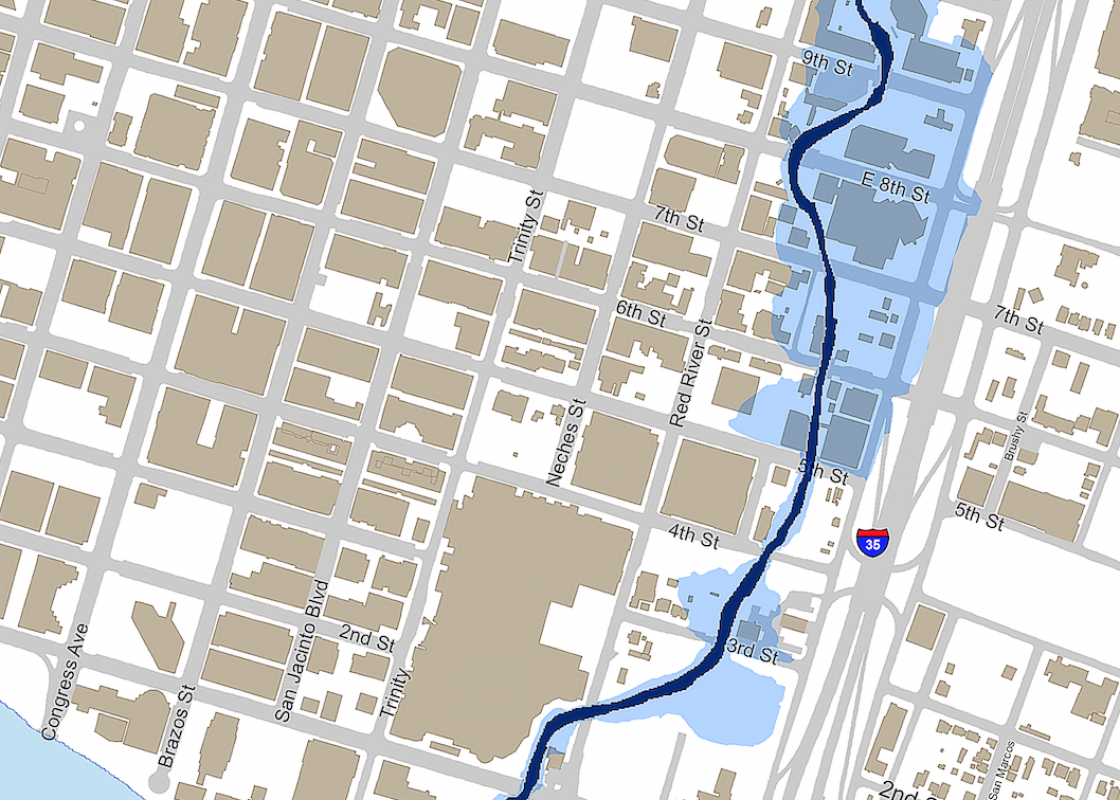

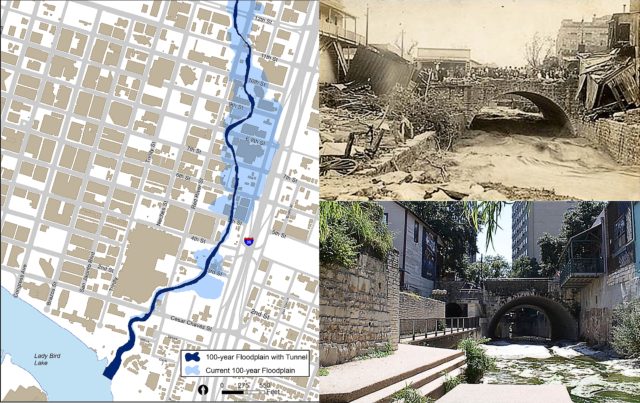

The creek is certainly a historic natural feature, but plans for its improvement have a long history of their own. Flooding was a constant threat, and as a result the low-lying areas adjacent to the creek attracted—and still attract—the homeless and their impermanent settlements. According to the timeline on the WCC website, a flash flood in 1915 killed 12 people along Waller Creek. In 1938, Lyndon Baines Johnson visited the creek and “decrie[d] 'the shanties' and 'hot beds of crime.'” Symphony Square was built in 1976 as a bicentennial revitalization of the area: Historic homes were moved to a single property and an outdoor amphitheater was built, with the creek-as-moat running between the audience and the stage. In 1997, the city passed a resolution to initiate discussions about how to improve Waller Creek. In the 2015 Memorial Day flood, high water still raged through the creek's constricted areas. Today, it is a pathetic sight, as its lower stretches are overgrown and clogged with trash, access to its eroded banks is limited and discontinuous, and the homeless seek refuge under bridges. It feels underutilized, even abandoned, as the photography included here by Leonid Furmansky and earlier documentation shows. In a few years, this will all change.

Waller Creek between 7th and 8th Street. Photo: Leonid Furmansky

Waller Creek between 7th and 8th Street. Photo: Leonid Furmansky

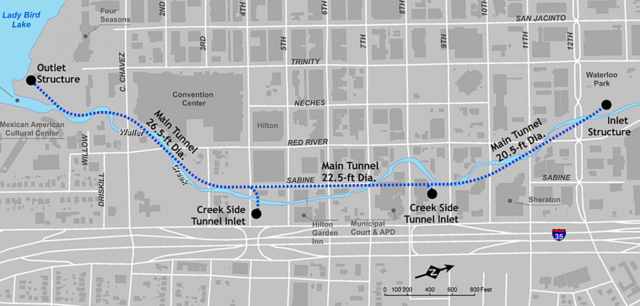

The turning point is the new Waller Creek Tunnel, a categorically Texan solution to the issue of urban flooding. In 2011 the City of Austin began work on a tunnel to collect Waller Creek's storm surges at 12th Street and to channel them underground to Lady Bird Lake. The intake facility at Waterloo Park has faced its own string of delays and cost overruns but is now working, moving water underground to emerge from a limestone slab-clad pool along the lake. It holds over 21.5 million gallons of water and is kept full at all times. At a final cost of almost $163 million, it virtually eliminates the risk of downtown flooding (water levels will not rise more than 4-5 feet). Its infrastructure will also regulate the level of Waller Creek: a computer-controlled pump moves lake water up to 12th Street, where it will then travel down the creekbed back to the lake. The main tunnel has been operational since the summer of 2015, and the two creek side tunnel inlets remain under construction.

Map of Waller Creek Flood Control Tunnel, inlets, and sizing. Map: City of Austin Watershed Protection Department

Map of Waller Creek Flood Control Tunnel, inlets, and sizing. Map: City of Austin Watershed Protection Department

Waller Creek Flood Control Tunnel under construction. Photo: City of Austin Watershed Protection Department

Waller Creek Flood Control Tunnel under construction. Photo: City of Austin Watershed Protection Department

This means the future of Waller Creek is a truly synthetic one, where its flows are regulated and managed to maintain appropriate water levels. Similar technology was used in San Antonio to create the Riverwalk. But unlike a steady-state model that retools ecology into amusement park, this park aims to recreate natural creek flows. There is still a pathway for water to flow normally through the dam at Waterloo Park into the lower stream, meaning that flow occurs in wet weather. The real art comes with establishing flows during drier parts of the year. Via email, Gullivar Shepard, project lead from MVVA, describes the operational complexity of the new creek, writing that "the municipality of Austin is now the curator of a mile-long stretch of nature. Seasonally variable flow rates — dry-downs and intense storm flows typical of a Texas creek — are critical for ecological function of the system. Now, at Waller, these variables are controlled through mechanical means at the inlet facility and will be refined likely over many years as a series of protocols to establish artificial storms and dry-downs calibrated to this specific creek system."

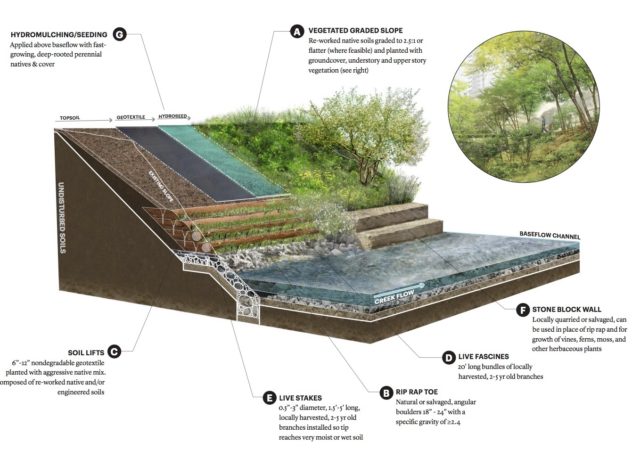

Kristin Pipkin, a City of Austin civil engineer with the Stream Restoration and Stormwater Treatment Program, says the schedule for the creek's water levels is still in development. Rather than running continuously as a kind of "babbling brook," seasonally-appropriate dry spells can even be educational. Pipkin said, “People are going to think if you can control water, you're always going to have water in the channel. But if it doesn't best support the ecology, it might be good to have those dry periods.” Her team is using data from multiple creeks with similar conditions to develop its operation. Water will even emerge from a stone seep behind a wall of limestone blocks, similar to natural springs in the area. Put another way: In this managed state, Waller Creek stands to become the ideal Hill Country stream.

Over the past decades Waller Creek has been compromised through alteration, pollution, and neglect to a state that is naturally artificial, with swales of trash, elevated levels of E.coli, and concretized embankments. This future Waller Creek will be artificially natural, with extensive updates that transform the waterway (back?) into a functioning ecosystem.

Shepard calls Waller a “cyborg creek,” revealing a speculative vision of how an urban waterway could function as hybrid of the natural and the mechanical in order to improve ecological performance. Here some amount of “naturalness” is compromised, but the result is both more biodiverse than what existed previously and more successful as an urban space.

“The cyborg creek helps provide a balance of sort between the goal of high ecological function for the creek and the high value public space for the trail/chain of parks proposal overlaid on the creek system,” Shephard wrote. The effort is a re-invention of a “typical Texas creek,” and seeks to “mediate between the voices of conservationists, whose knee-jerk reaction to these topics is going to be how to mediate the amount of change, and the urbanists that recognize how much is changing in the creek, along the creek, about the creek and whose knee-jerk reaction to these topics will be to contemplate even more change.”

The "re-" prefix abounds, but it's not so much turning back the clock to create a pre-Austin Waller Creek as initiating a new ecological terrain that works for the city of tomorrow.

The design has been visioned through a comprehensive Framework Plan. If followed, the creek banks will largely be renovated into stabilized, naturalized slopes, with special attention paid to revitalizing riparian habitats, the realization of limestone-like cliffs in concrete or with caliche blocks, and intensive planting strategies. Areas for recreation, play, and contemplation are given equal consideration to “end-of-pipe” pollution fixes, fish habitats, and the slowing of run-off. Pipkin told me that fish ladders are included at the three inlet locations, allowing the animals to still be able to freely move upstream. Ecology and civitas are improved through a single initiative. To this end, WCC CEO Peter Mullan reflected that this is “really a synthetic landscape.” Even though the water flow is technologized, “all the processes that are here will be natural processes. In reality this idea of a pristine, real nature, doesn't exist anymore.” Mullan is well aware that using this piece of infrastructure to recreate a functioning ecosystem is perverse, but “it speaks about our relationship with nature as not putting walls around the natural realm to preserve it, but recognizing we're in a managed relationship with nature — that you have to manage it. Waller Creek is one expression of that in the urban environment. It's both 'How do you preserve the environment?' and 'How do you make cities livable?'

The proposed Waller Creek Park revitalizes existing open spaces — Waterloo Park and Palm Park — while improving the creekbed into a “ re-naturalized condition.” The vision routes pedestrian and bicycle traffic along the creek and calls for a number of activity centers along the pathway. The forthcoming Waller Creek is a mixed-use proposition, where a park is both place and pathway in the 21st century city.

“A lot of what we're trying to do is to reconnect the space of the creek to the city around it,” says Mullan. Trained as an architect, he came to Austin after spending eleven years leading the design and construction of the High Line in New York City, eventually in the role of executive vice president at the Friends of the High Line non-profit. He describes the design of Waller Creek Park as a surface with a continuity of use between levels. The Framework plan calls for clear lines of sight at street-to-creek transitions, where access occurs on wide graded paths (under 5 percent slope) without the use of switchbacks or elevators. At 7th Street, for example, where creek access is tight, bike traffic will be routed up onto Sabine Street before rejoining the creek at 4th Street, promising a seamless and intermodal experience, where a park could become “a platform for making connections, both physically and culturally.”

Waterloo Park is the first phase slated for construction. It will include an amphitheater designed by Thomas Phifer and Partners and a great lawn that arcs over the creek intake facility, set among winding paths with Hill Country plantings. Mullan estimates its completion by 2019. Much like the creek's subterranean pump recirculates water, the park will invite different communities to ambulate in productive cultural collision.

While design and fundraising efforts are underway, the Conservancy, founded in 2010, has already started to reintroduce citizens to the creek. For two weekends in November, its popular Creek Show hosts a series of temporary, light-based installations in and around the creek; over 10,000 people attended in 2016 (I worked on an installation with Baldridge Architects for the first Creek Show in 2014). Art as placemaking is a key way to reactivate transitional public space, and to that end, WCC President Melba Whatley made a gift of $1.1 million to The Contemporary Austin in 2016 for “ future collaborative art programming with the Conservancy along Waller Creek.” Earlier this year, Austin's Moody Foundation announced a $15 million grant to fund the amphitheater in Waterloo Park, called the “ largest philanthropic gift devoted to parks and open space in Austin's history.” To date, the funding for overall park, estimated to cost $220 million, with about $42 million from the city. Other funding will hopefully come from philanthropic donations but Mullan hopes it will ultimately settle more evenly between public and private sources.

Waller Creek Park precedes the coming development of the eastern portions of downtown. The tunnel removes 28 acres of real estate from the floodplain, opening these tracts to more intensive CBD improvements. The park is, in Mullan's thinking, “all in anticipation of a lot of density coming to this part of the city.” Rather than carving out park space from an existing cityscape, this linear park is installed first and will focus private development along its edges. Over the years, as the city densifies around the creek, its experience as an urban oasis will only intensify. And, properties facing the creek will hopefully capitalize on an opportunity to open towards the creek, rather than turning away. In many ways it is forward thinking to install landscape architecture as a public utility prior to new construction, so it can behave as a district-wide catalyst. The goal, Mullan says, is for the public realm to be “the lens through which the development of that district is filtered.”

Viewed together with the Reconnect Austin proposal to sink I-35 and the forthcoming Innovation Zone south of the new Dell Medical campus, Waller Creek Park suggests a future of walkable connectivity and density in eastern downtown Austin. Soon, you may be able to walk from the new medical campus at UT to Lady Bird Lake without encountering a car. Or, you could take the overland route along the park that may cap a buried highway, recalling the old East Avenue before the interstate arrived. It will take a strong coalition of leaders working together for many years to realize these urban visions. Large problems remain, including how to better serve Austin's homeless community, who gather in the area adjacent to the ARCH and along Waller Creek; and how to maintain the Red River Cultural District, where music clubs fight to stay open despite rising rents. These issues are part of the serious ongoing battle to keep Austin equitable.

If this transformation results in a cyborg creek, then the wider vision for Waller Creek is a kind of cyborg urbanism. Ecological and urban hybridity opens up new symbiotic opportunities for humans and wildlife to co-exist in a space where human impact can actually increase biodiversity. This description also suggests an analogous new economy, one in which public, private, and non-profit entities join together to stimulate environmental and urban processes faster than through government regulation or traditional market forces. The conservancy model bundles activism, visioning, management, and fundraising to create focused stewardship of a particular geography. As the essay to follow in this series will show, it is already at work at other parks and creeks in Austin, as well as in parks throughout the country. Central Park's conservancy was founded in 1980, and Houston's Buffalo Bayou, Discovery Green, and several others have their own.

Because transformation of Waller Creek is a new and unique effort, its outcome may very well set the standard for how these projects can be realized in the future. Shepard writes, “In many ways, this is a setup, not the end-game solution. The real work comes in how the City of Austin and the Conservancy evolve with the project — how public-private ventures might enable a way of collaborating with nature instead of falling back into the modern historic model of controlling nature.” Following the High Line's example, we now know a linear green space is not just an urban parkway, but also a new pathway for simultaneous ecological and economic improvement. Will Waller Creek do the same for Austin? Time will tell.