Westerpark in Amsterdam.

OffCite continues its coverage of responses to Hurricane Ike and, more broadly, efforts to adapt coastlines to rising sea levels and frequent mega-storms with a post by writer Zachary Martin.

Houston may have less than a year to decide how it’s going to survive the next big storm to strike Texas, according to Thomas Colbert, a Professor in the College of Architecture at the University of Houston and former chair of the Cite editorial committee. He was speaking at that university’s “Dynamic Equilibirum at the Water’s Edge: Three Continents Symposium” last week when he stated his belief that even the devastation caused by large storms like Ike and Katrina has a tendency to fade from public memory after about five years, making massive infrastructure projects like dikes and levees much more difficult to find support for, let alone fund and build.

Coming in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, the two-day symposium served to perhaps prolong the conversation a bit longer, long enough to debate the relative merits of a number of plans that have been put forward to protect the Upper Texas Coast and Louisiana wetlands. On hand were researchers, architects, and academics with vast experience in water strategy and management: David Waggonner, of Waggonner & Ball Architects in New Orleans; Jeff Carney, director of LSU’s Coast Sustainability Studio; Michael Rotondi, principal architect of RoTo in Los Angeles; Flavio Janches, professor at the University of Buenos Aires; Diego Sepulveda, professor at the University of Delft, in the Netherlands; and Thomas Colbert, among others.

While the presenters were gathered from three continents, the symposium made one thing apparent: the vast majority of countries treat water as a liability, rather than as a resource. Waggonner spoke first and made abundantly clear that the Dutch were in the vanguard when it came to strategies for dealing with floods because their low-lying country had taught them not to be afraid of water. In laying out his vision for the potential future development of New Orleans, Waggonner showed how safe levees could be built with public use in mind, tearing down the ineffective walls that failed during Katrina and served only to divide neighborhoods and increase urban blight.

By drawing on Dutch models, Waggonner outlined ways in which levees could become public parks. Most of the year, these parks would serve a recreational purpose (and demonstrably boost local property values); when disaster struck, the low-lying parks could be flooded, siphoning off hundreds of thousands of gallons of excess water from nearby neighborhoods and averting residential flooding. What prevents us from taking these kinds of steps, Waggonner said, was fear. The paradigm of water as a resource rather than a threat is a difficult message to impart in an era of “superstorms.” The Harris County Flood Control District has taken this approach, to some extent, as discussed in "Buried Concrete" in Cite 86 and "The Flood Next Time" in Cite 46.

Jeff Carney followed, and expanded on, Waggonner’s thoughts by showing the ways in which this fear-driven thinking has impacted even non-urban areas along the Louisiana coast. By creating dikes and levees to attempt to control the flow of the Mississippi, Louisiana has done a grave disservice to the wetlands west of New Orleans, which depend on an influx of silt from the great river to prevent coastal erosion. The numbers he offered were startling: in the last eighty years, the wetlands south of the I-10 corridor between Houston and New Orleans have shrunk by 1,880 square miles, with 1,750 square miles more predicted to be lost in the next fifty years. The unaccounted value of this land? Carney provided an estimate of twelve billion dollars.

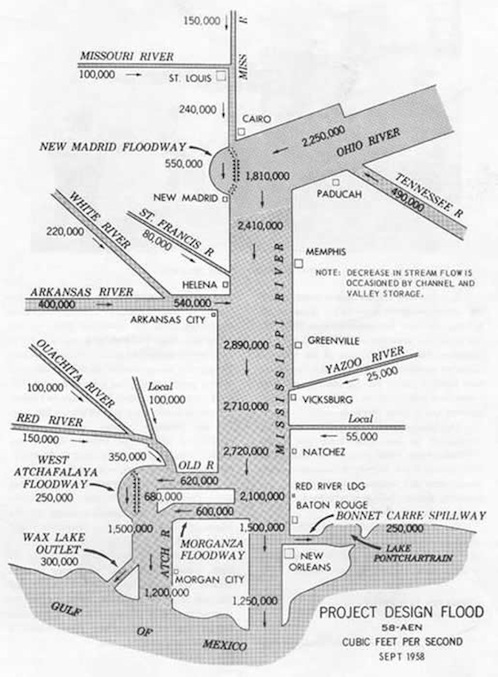

Carney, showing a map from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that revealed the folly of trying to impose a man-made schematic on a complex and dynamic natural system, advocated for a move toward a more natural system for the I-10 corridor that seeks broad changes across state lines. Such a vision would see local communities and state governments partnering to allow smaller tributaries of the Mississippi access to the Gulf of Mexico to begin reversing erosion damage and allowing silt deposits to build new wetlands that would serve as a natural barrier to future storms. Left open was the question of how to activate local communities to work together for the common good, especially when what might be good for one community of, say, shrimpers, might be detrimental for a nearby community of oil workers.

While Flavio Janches’s subsequent presentation centered on water strategies in the slums of Buenos Aires, he superbly demonstrated some of the reasons why, even as climate change wreaks havoc on coastal regions across the world, the indigent population in floodplains across the world continues to grow. Simply put, their poverty requires easy access to water for drinking, for sewage, for washing. The same forces that drive the increased population into low-lying areas, however, also ensure that their water supply will continue to grow more and more polluted, especially with the majority of world slum growth predicted to occur along the waterfront in the next century.

Part of the solution, Janches contended, was to use a water strategy that has “unslumming” potential, and he presented a number of public works designs that provided access to water while also ensuring protection from flood conditions, minimized pollution, and offered the local environment a chance to regenerate from decades of abuse. The economic forces at work in a country like Argentina might differ from those in the United States, but Janches clearly echoed the notion that a culture that respects water as an amenity need not fear it as a destructive force.

Thomas Colbert closed the first day’s presentations by bringing the importance of water management and strategy directly to Houston’s doorstep. As a researcher for the Texas SSPEED (Severe Storm Predication, Education, and Evacuation from Disaster) Project, Colbert is working with other researchers from across the state to develop an adequate public policy to protect against future storms. He began by outlining the risks if Houston fails to prepare itself in the new era of climate change, stating that if Hurricane Ike had made landfall even a few miles west of where it met the Texas coast, some areas of Houston cold have seen a far higher storm surge. That kind of risk to the nearby Port of Houston, which is directly responsible for as many as one million U.S. jobs, is simply untenable. But not only jobs could be impacted. Colbert said that Professor Hanadi Rifai at the University of Houston has identified almost 2,700 chemical storage tanks that could have been inundated if Ike, a mere Category 2 storm, had hit the coast a few miles to the west of its final landfall. Any tanks that collapsed would have spilled their chemicals into Galveston Bay and onto surrounding communities.

Preventing catastrophe, according to Colbert, will almost certainly require dikes and levees, but he was careful to point out that bigger isn’t necessarily always better. Some have advocated for the “Ike Dike,” which would extend along the entire coast from High Island to Freeport, Texas. Besides being prohibitively expensive, logistically difficult to build, and ecologically unsound, Colbert presented computer models that showed the Ike Dike would not protect the Clear Lake region against storm surge. Even with the Ike Dike in place, a Category 2 storm could create a 16-foot storm surge into the Clear Lake area.

Colbert stated that he felt his role and that of fellow researchers was to present a “menu of alternatives.” Along with a Galveston Bay waterfront levee proposal and other local levee proposals, one of the proposals that he discussed in depth was the possibility of raising Highway 146, which stretches between Baytown and Galveston, to serve as a dike. The advantage of such a plan would be that the highway would not need to be raised much above its current height, and the cost could be split among a number of government agencies. The disadvantage is that places like Texas City, San Leon, and La Porte would all find themselves on the wrong side of the levee, and receive little to no protection in the event of a direct hurricane strike.

Cheaper alternatives to the "Ike Dike" include a gate at the Ship Channel.

Another alternative to the "Ike Dike" would protect dense areas of Galveston.

This was perhaps the most interesting aspect of the symposium for a non-expert like myself: the rather casual way in which professionals familiar with water management had to confess that not every community could be guaranteed protection. Communities that find themselves behind the levy, could afford to be more densely built; communities that are not protected by levees might find their land unbuildable after the next big storm.

Colbert also presented an alternate vision that was similar to the one provided by Jeff Carney: a natural barrier to future storms, one that would also serve as an economic boon to the region. Called the Lone Star Coast National Recreation Area, there is a substantial force advocating for vast swathes of the Upper Texas Coast to be voluntarily developed for recreational purposes rather than urbanization. The goal—which is ambitious, but perhaps no more ambitious than plans to wall off the entirety of Galveston and the Bay—is to have local, state, and federal governments, as well as local landholders, working together to improve the ecological value of the Upper Texas Coast and market it as an eco-tourism destination.

Already, areas like the Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge attract tens of thousands of visitors every year, and supporters of this project believe that the Upper Texas Coast as a whole can become the next Ebey’s Landing, Boston Harbor Islands, or Timucuan Preserve. With an estimated forty-eight million bird watchers and seventeen million canoers, kayakers, and hikers spending an estimated thirty-six billion dollars each year on their hobbies, it doesn’t necessarily seem an outsize proposition.

Before opening up the floor for questions during a later roundtable discussion, moderator Michael Rotondi made an effort to sum up the symposium. He talked about the importance of considering dynamic systems that took into account our changing landscape and our changing needs as a society versus the single state systems like those proposed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that showed a great deal of hubris in thinking that they could overlay the natural landscape with the built landscape of mankind without dire consequences. Problems at this scale, he said, have the potential to bring us together as a society, and even someone in the audience like me, a mere writer, could understand that there might be a way to contribute to the effort.