In the process of developing Cite (93), a special issue on the environment, guest editor Tom Colbert and I drove all around the Houston region, from the bay to the piney woods, photographing landfills. We were inspired by Dr. Robert Bullard, a contributor to the issue. His 1979 study of solid-waste disposal in Houston revealed that five out of five city-owned landfills and six of the eight city-owned incinerators were sited in Black neighborhoods. That research helped spark an international environmental justice movement. In his article for Cite, Bullard describes the low-tech methodology behind the 1979 study: "If we noticed a hill in the usually flat landscape, we investigated it because a change in topography often indicated a dump."

With that history in mind, Colbert and I wanted to create a comprehensive photographic guide to Houston's "mountains," but our region, it turns out, has far more manmade changes in topography than a team of two can document over a couple of weekends. In this post, I share a series of photos that show one of the most mind-boggling sites in the Houston area, the Alps of Pasadena.

If you drive on the Pasadena Freeway (State Highway 225), which is part of the Freedom Trail to the San Jacinto Monument, you'll see the mountain range to the north between Red Bluff Road and Beltway 8. According to the homepage of the current owner, Rentech Nitrogen, the facility is the "largest producer of synthetic granulated ammonium sulfate fertilizer in North America."

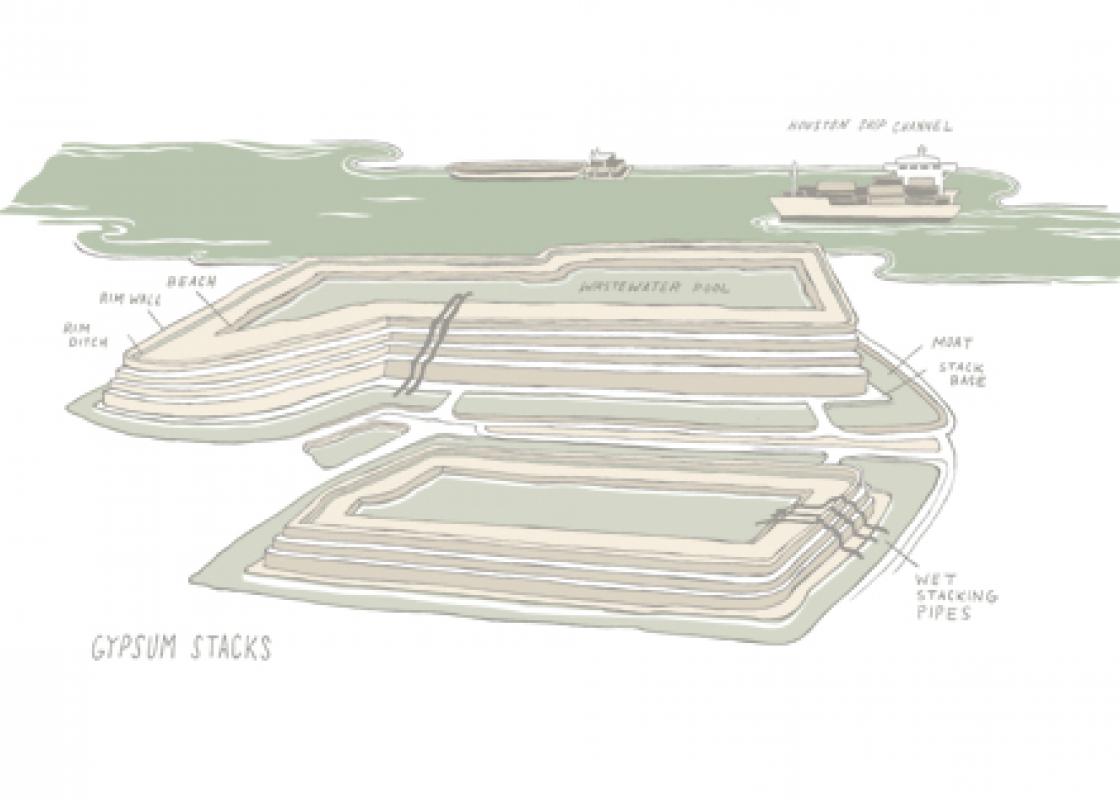

Why does the production of fertilizer create mountains? The process yields a toxic waste water, which is stored in pools. The water evaporates and leaves behind the phosphoric gypsum. Gradually, the evaporate accumulates as one pool after another is dried up on top of the last, forming what is called a "gypstack." The best description of this site that I have read comes from the Center for Land Use Interpretation's tour of the Ship Channel (published in 2009 before a change in ownership of the site):

This is a phosphate plant, making components for fertilizers. The company handles hundreds of thousands of tons of sulfuric acid and phosphoric acid a year, and generates a literal mountain of byproducts, stacked in mounds nearby. The phosphate rock for the plant comes by ship from Morocco, the major global source for phosphates. Built in World War II, the plant has been owned by Olin, and Mobil. Agrifos bought the plant from Mobil in 1998, and manages it today, with over 200 employees.

Behind the plant is a network of rectilinear mounds known as “gypstacks,” which have grown over the decades of operation of the plant. . . . The gypsum is tainted with enough acids and other materials that it is not marketable, so it just piles up.

If you dare to drive on the little roads between each gypstack, you'll notice various safety measures like plastic liners, ditches, and berms to keep the toxic water from leaking out. Many of the slopes are planted with grass. On one visit several years ago, I saw a horse grazing at the base of one. If I squinted, I could imagine myself in Montana, if not the Alps.

The gypstacks are hard to photograph because of their horizontality. They are more like plateaus than mountains. You can't appreciate how tall they are without being there. In one photograph, a pickup truck at the peak gives away the extraordinary scale.

If it rains hard enough, the various safety measures can fail. According to this 2008 EPA report on the site, "Several releases from the gypsum stacks have caused the discharge of millions of gallons of untreated process water from the facility to the surrounding environment." The surrounding environment is the Houston Ship Channel and Galveston Bay.

This subsequent report from the EPA after a January 2, 2013, settlement provides additional detail: "On August 16, 2007, the site received an estimated eight inches of rainfall which contributed to an excess of process and stormwater within the stack, thereby causing a failure of the retaining wall surrounding the stack." As alarming as the release of water with a pH of 2 sounds, the detail I find most fascinating is that one of the gypstacks is 240 acres big.