For more articles like this one by Christopher Sperandio, subscribe to Cite or call (713) 348-4876 to purchase the forthcoming special issue on museums that includes an article by Walter Hood on Project Row Houses.

Part rockstar-style tour bus, part utility vehicle, and ultimately a blank platform that sleeps six, Cargo Space has crisscrossed 7,000 miles of this country with Houston as its base. We hold one-night events and host all manner of functions, playing host to cultural workers of every stripe (local, national, international). It's great fun that is rooted in an urgent art form called Social Practice. To explain the Cargo Space project any further, let's step back for a moment, review some history, look at contemporary debates roiling the art world.

Social Practice---an underknown art form rooted in the Conceptual Art and political activism of the 1960s---is alive and well in Houston, but for how long? Social Practice and the communities it engages are facing a real challenge for efficacy in the face of massive social and political upheaval, specifically the gonzo real estate market and the growing gap between the haves and the have-nots.

You might not have heard of Social Practice for a couple of reasons. First, as a field of art practice it goes by many names: Relational Aesthetics, Community Art, Socialized Art, Social Art, or New Genre art, to name a few. Just as it defies labels, it’s also a field of art-making that has historically resisted commodification. With a few exceptions, say Chicago’s Theaster Gates, whose ceramic and sculptural works are gobbled up by collectors, Social Practice artists generally don’t make products that fit easily within the luxury consumer goods industry into which most art making has been absorbed.

If you haven’t been paying attention to Social Practice, you soon will.

Artist Sara Daleiden leading a discussion in “Regional Poetics” as part of the Cargo Space residency at the Institute of Visual Arts, Milwaukee. September 2014.

Artist Sara Daleiden leading a discussion in “Regional Poetics” as part of the Cargo Space residency at the Institute of Visual Arts, Milwaukee. September 2014.

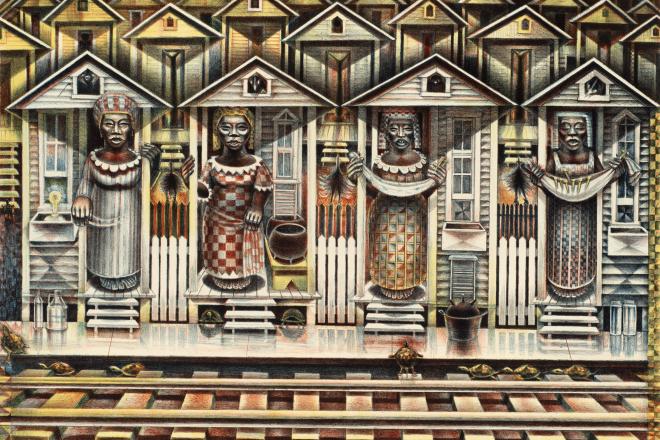

Rick Lowe, the Houston-based founder of Project Row Houses (PRH), was awarded a MacArthur Prize in 2014. Lowe began Project Row Houses in 1993. You can also see his legacy in Otabenga Jones and Associates (OJ&A), an artist collective that coalesced around PRH. They’ve had some traction nationally, first through their appearance in the Whitney Biennial, and this year in a project for New York’s Creative Time. Mel Chin, artist and Houston native, also figures into the social action and political history of Social Practice. Although not based here for some time, Chin continues to be a figure on the scene---numerous local institutions showed a retrospective in early 2015. Just as there are as many names for the field as there are artists, there are claims for the birthplace of Social Practice, the most American art form.

Rick Lowe compares the methods of PRH to those of Joseph Beuys, a German artist who began working after World War II. I have been involved in "Social Practice" before the inception of the term. In 1989, British artist Simon Grennan asked me to collaborate with him on a large-scale, community-based artwork. Reported in the Chicago Sun-Times and the Chicago Tribune and in the (now defunct) New Art Examiner, it was centered on five urban churches in Chicago. At the time, we were both MFA students at the University of Illinois. Filled to bursting with the works of the Situationists, Pierre Bourdieu, and the Frankfort School, and consequently disaffected with the studio as a site of meaning, we set about to make a new kind of artwork, one that took place away from the standard art world demography, and to make work that was more in line with our daily, working-class experience.

Following on the heels of our first Socialized artwork (our term at the time), Grennan & Sperandio participated in the 1993 Culture in Action exhibition in Chicago. This show brought together local and national artists to develop new, collaborative New Genre art works, and received a tremendous amount of international press. Within a few years we began to notice many more artists working in ways that roughly fit our working methods. Social Practice is now a field that’s on the move---to the point that it’s become an area of study, like drawing or printmaking, at several universities nationwide.

For the most part, Social Practice has, as a chief component, a direct engagement with an audience. This audience is, typically, not part of the gallery or museum-going crowd, although they can be. Cast in the role of “community,” the direct participation of others in the development of a new Social Practice artwork is often the main subject of the resultant artwork. The discursive nature of the work itself often leads to the criticism that documentation of Social Practice (photographs of people meeting and talking) all looks the same. Although, an educated view could see this as a variation on the “my kid could do that” criticism leveled at the masters of Abstract Expressionism.

A perfect example of visualized discussions is the recent OJ&A work for Creative Time in New York, entitled OJBK FM Radio. The documentation of this project is of people speaking to each other. However, OJA smartly cracked the “sameness” criticism by dressing the setting of the conversations. The collective collaborated with the Central Brooklyn Jazz Consortium to produce a temporary outdoor radio station, broadcast (and photographed) from the back of a hot pink 1959 Cadillac Coupe de Ville. It was a custom sculptural setting for the resulting programmed discussions that took place on their temporary radio station. The group’s work, like most Social Practice work, includes actions, writings, and installations. With OJBK FM Radio, the group’s mission, in the words of the late Russell Tyrone Jones, was to “teach the truth to the young black youth.” A discussion of the history of the neighborhood abounds in the online literature for the project. And herein lies the chief problem that faces Social Practice, at least in Houston, and it’s not the sameness of its documentation, or the lack of a “product.” The problem, in particular one facing an organization like Project Row Houses, is the shift in community brought about by gentrification.

It’s in the news: the enormous gap between the haves, the ultra-haves, and everyone else. The gobbling up of historical neighborhoods has a dramatic effect on the field of Social Practice. In the land of the “free,” communities in the U.S. are at the mercy of developers and gentrification. In Houston, redevelopment has taken the form of massive, city-block-sized “luxury” condominiums that have erupted like a very bad case of acne across the nose of this adolescent city. Questions and implications for Social Art abound in the context of gentrification. Will Social Practice be an agent of change, or ultimately another tool of gentrification?

The dramatic uptick in the local housing market has not gone unnoticed by PRH. They’ve warily eyed the redevelopment creeping across Houston. Several years ago, PRH began actively acquiring the property around it both as a hedge against developers, and as an effort to help stabilize the community around it. They have collaborated with Rice Building Workshop to create affordable housing. PRH properties, in addition to their exhibition spaces, and housing for single mothers, now include a food co-op and the El Dorado Ball Room, a multifunction events facility. Row Houses’ efforts are a remarkable move. Although the encroachment has been slow, the economic tide is sweeping across Highway 59, heretofore a natural barrier between the section of the historic Third Ward branded as Midtown and the area widely considered the Third Ward, an African-American neighborhood sandwiched between 59 and the University of Houston. What happens if (when) the redevelopment continues unabated? A rising tide floats all boats, but what if you don’t have a boat in the first place? People are facing a real dilemma of affordable housing. PRH’s creative response is to expand, helping to anchor the community around it, but without some sort of larger social and economic change, Row Houses faces the real possibility of someday being a community-based artwork located in a neighborhood of luxury town homes and sprawling block-sized condominium complexes.

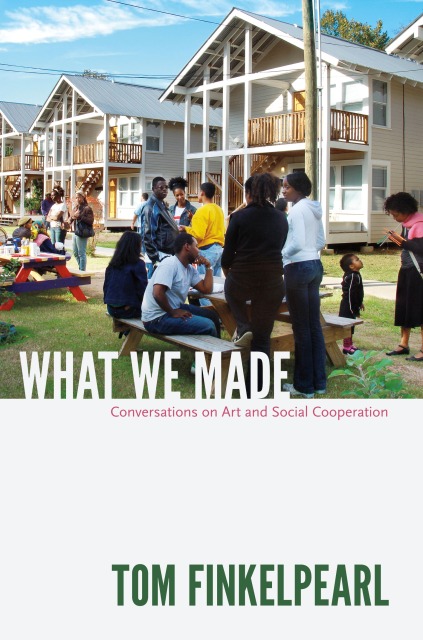

In an interview published in the book What We Made: Conversations on Art and Social Cooperation, Lowe said, "So much development of urban neighborhoods is being driven by land values, and it’s causing a demographic shift. So the question is, do we have to allow the shift in demographics to take place as it’s happened in the past, where one group comes in and the other moves out, or can we create opportunities for a kind of staying period for this diverse population?"

At the recent RDA civic forum on Houston's wards, Assata Richards, Community Liaison for Project Row Houses, was more direct. "The fight is not over, Third Ward must not be sold," she said.

One response to gentrification, and the inequity gap is a change of scale. Through the Rural Studio program at Auburn University, students design and build homes on a budget of $20,000. Small by Houston standards, these 600 to 800 square foot residences are priced for those receiving median Social Security checks. The XS and ZeRow houses by Rice Building Workshop at Project Row Houses build on this model.

Small living in DIY trailer homes (most under 200 square feet) is another radical act. Those without wealth can build and own their own home, a concept that would otherwise be unthinkable to a vast majority of today’s working poor. Building these small homes on trailers is smart, in that it (for however long) allows the small-time builder to skirt prohibitive regulations relating to home construction. Increasingly, low-income individuals are looking at a variety of options, even rehabilitating used school buses, transforming them into small, functional single-family dwellings.

I have attempted to bring mobility and small living into Social Practice in the form of the Cargo Space in collaboration with Grennan. A rolling living space for artists, the Cargo Space is built inside a reconditioned diesel transit bus. Cargo Space, an effort seeded by the Humanities Research Center at Rice University is the Grennan & Sperandio reaction to politically charged real estate and gentrification issues. A living space in a functional bus, Cargo Space can relocate with the shifting tides of communities. Primarily engaging artists as an underserved community, it’s intended as an opportunity to bring more artists to Houston, and to take Houston artists out, crossing the great geographic distances that separate Texas from the rest of the country. The Cargo Space has traveled over 7,000 miles in its first year of existence, with more than 20 artists participating.

Social Practice is, in my view, an art form practiced by working class artists. Why struggle for change, if the world is your oyster? In other words, a key motivator for artists is a feeling of alienation, in the most Marxist sense, if your background or experiences sit outside the now corporately established societal norms of upward mobility, and an ever-increasing acquisitiveness. While many critics harp on its idealism, and the lack of a product, the idea of Social Practice has appeal. Social protest movements, whether the Occupy movement, or the more recent rage expressed at the police shootings in Ferguson, Milwaukee, and nearly every other city in the country, operate more as a release valve for emotion, rather than as a laboratory for viable alternatives. Whether or not artists can salvage a bent or broken social or economic system, Social Practice remains an essential field of investigation and one which simultaneously critiques the institutionalized radicalism of established art practice and academia. The artist as urban planner, or socially engaged participant looking for solutions, as opposed to artist as luxury goods producer, is a genuinely radical notion. If, that is, you haven’t been paying attention.

Christopher Sperandio is an Associate Professor teaching art at Rice University. Grennan & Sperandio are acknowledged as pioneers of interventionist, New Genre, and post-relational practice, in publishing, television, and social action. For more information on the Cargo Space, visit thecargospace.com.