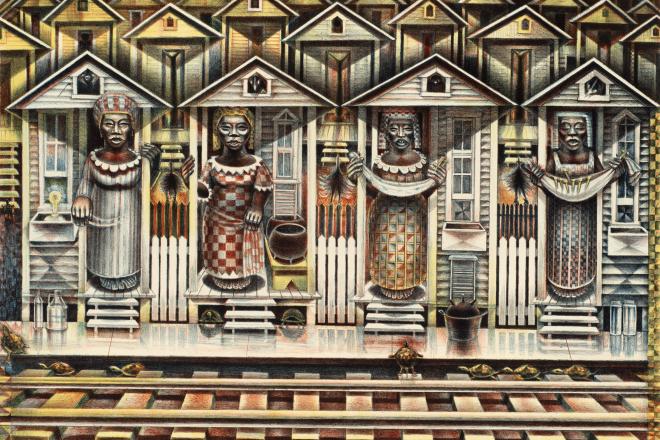

Karachi headquarters office of Emaar, a Dubai-based real estate company [Photos Sehba Sarwar]

At a March 2009 ceremony in Houston, Mayor Bill White and Syed Mustafa Kamal, the mayor of Karachi, Pakistan, declared the two cities sisters. The connection between the two cities was not new to me. Back in 1992, when I followed my then-boyfriend-now-husband René to Houston, I remember absorbing concrete sprawls of apartment complexes, and thinking of Karachi, my home city. Since then, over the years, I’ve been writing and exploring the multiple parallels between Karachi, where I return often, and Houston, where I’ve been based for some time.

With a population of 16 million, Karachi is four times as dense as Houston. Most of the city is concrete, with open trash and few trees. But much like Houston, there is richness to be uncovered. Close to the seawall stands the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture built from sandstone structures recovered from the city center, and in the old city center is Khajoor Bazaar with open lanes stacked with chest-high mounds of fresh dates. Similarly, I had to immerse myself in Houston for a while before uncovering spaces such as the Menil Collection and surrounding neighborhood, the winding walk along Buffalo Bayou, and the drive down the sun-speckled section of Main Street parallel to Rice.

Both cities have quirks. In Karachi, donkey carts trot alongside decorated trucks and buses, while goats nibble on rotting fruit at busy street corners. In Houston, police officers often patrol on horseback, and, on 288 South, cattle graze in fenced fields minutes away from the Medical Center.

Ultimately, these are surface similarities. The March 2009 declaration of Karachi and Houston as sister cities made note of commercial and industrial ties. For me, the cities are intertwined through their mutual ethnic and race conflicts and demolished historic spaces.

During the 1800s, Karachi was a spacious and sleepy fishing village, but that changed a century later once the British began to use the city as a seaport. In 1947, after Partition, Karachi emerged as Pakistan’s capital, and its population exploded to accommodate muhajirs (immigrants) from north India who took over the country’s industrial sector. The mix of local population with newcomers has been violent—during the nineties, a civil war erupted in the city as indigenous Sindhis tried to reclaim the power they lost to muhajirs. Today, though Karachi hasn’t been the capital since the sixties, more ethnic groups continue to pour into the city. Currently, most of the violence has subsided, but tensions continue to simmer, given the turbulence in northern Pakistan.

Houston is also a young city. As its demographics shift and change, it too has experienced racial tension at different points in its history. During the sixties, in Houston as in the rest of the US, blacks fought hard in the desegregation movement. A decade later during the late seventies, many Chicano/as expressed rage at racial discrimination through the Moody Park protests. Currently, more than 60 percent of Houston’s population consists of communities of color. Many from this population are successful, but school dropout and incarceration rates are disproportionately high. Additionally, housing and “redevelopment” are daily battles in which citizens of color engage: historic black neighborhoods such as Freedmanstown and the Third Ward have changed radically with the explosion of real estate development by companies that tear down old structures to build new townhomes; the Eastside struggles to hold on to its Chicano/a roots as it gets ready to embrace a growth spurt; and southwest Houston, one of city’s most dense areas, is filled with immigrants from around the world who fight for basic amenities.

Clifton Seawall at sunset, Krachi, Pakistan. Photo by Sehba Sarwar.

In Kamal’s flashy presentation at the DeLange Conference at Rice University back in March, he marketed Karachi as “secure,” poised to become a great international city on par with Singapore. He boasted of major infrastructure development: “60,000,000 gallon water treatment plant, a 582 km long water distribution network, a 621 km long sewerage disposal network, 150 pedestrian bridges, 200 prefabricated bus stops, Signal Free Corridor 1 [a 13 km freeway], Signal Free Corridor 2 [a 22 km freeway], and a 5 km bridge.” His presentation was dotted with smiling images of himself at ribbon-cutting ceremonies. There was no mention of citizens displaced by major reconstruction, mangrove habitats torn down for roads, or of businesses affected in low-income neighborhoods. Nor was there any reference to Kamal’s political allegiance to MQM, the muhajir group that led Karachi’s conflict during the nineties.

Meanwhile, much in the way that history gets erased in Houston, in Karachi, historic buildings continue to be replaced with cheap structures. And areas where fishing villages have stood for centuries are being sold off to companies such as Dubai-based Emaar (one of the world’s largest global real estate companies), with the goal of creating a seaside resort. Once the resort is completed, people will no longer be able ride public buses to Hawkesbay or Sandspit beaches—that are located at the same distance from Karachi’s city center as Galveston is from Houston.

Often when people ask me why I live in Houston, I tell them: “I live here because it’s like Karachi: hot, polluted, and there’s no respect for history.” As an artist and community organizer, I continue to connect local struggles taking place on opposite sides of the world. While I’m glad that my two homes are now officially linked, my voice in both cities continues to be one of reflection and protest, seeking to capture histories that are slowly eroding.

Sehba Sarwar is a novelist, and multidisciplinary artist. She serves as the Founding Director for Voices Breaking Boundaries (VBB). For more information, visit her website at www.sehbasarwar.net. The next VBB event, Living Room Art: Honoring Dissent / Descent, will be held November 7, 2009 at her home.