Salina, Kansas, is a town like so many others in America. Its downtown stands as a reminder of what once was — brown paper is taped to the inside of windows, lackluster rental signs hang askew beckoning no one. Its vital economic lifeblood has drained to the southern outskirts where a Walmart and a Lowe’s dominate the placeless landscape.

These monolithic stores’ lack of connection to place, environment, and land, and their undermining of community, connection, and relationships, stands in stark contrast to all that the Land Institute embodies. We had arrived in Salina on the hot, windy plains for the Prairie Festival, celebrating the Land Institute’s 40th anniversary and the retirement of Wes Jackson, its leader. More than 1,000 pilgrims went to pay homage to a man and place that have inspired so many.

Perched roughly in the geographic center of America, the Land Institute seemed a good place to contemplate the flaws in our industrial agricultural system, consider alternatives to what we now consider the status quo, and explore possibilities — an agriculture that restores soil instead of depleting it, that doesn’t require chemical inputs, that is more resilient in the face of climate extremes and disease. Here, where undulating hills of thigh-high grasses gently bow in the wind, was a gathering of minds and hearts willing to wrestle our food supply and agricultural system out of the tight grip of a few powerful companies.

I couldn’t stop thinking about Houston’s Blackwood Educational Land Institute. And I felt excited to think that Blackwood is so accessible --- just north of Hempstead off 290 --- to such a huge population, a population desperate to learn the value of the land they are rapidly ripping up and filling with pavement and houses. In many ways, Blackwood embodies the principles of the Prairie Festival. As I listened to the Land Institute’s former interns and board members reminisce about the back-to-the-land, anti-establishment ethos that defined its early days and talk about building a newspaper house, rainwater collection tanks, wind turbines, and solar collectors (most of which were failed experiments), I thought of how many of these have since been executed well at Blackwood.

Blackwood Educational Land Institute became a non-profit in 2000, but has been operating as a nature education center since the early 1990s. Blackwood's founder and director, Cath Conlon, had a vision “to remind students of humanity’s intrinsic bond with the land, to teach the interconnectivity of all living things, and to suggest that great things can happen only if we realize that this interdependence extends to our families and our communities as well.”

The land had been in Cath Conlon’s family for years. It had been used to grow cotton. Because of the heavy industrial agriculture use, the land needed to be restored, which is still an ongoing process that the students who visit the land participate in. Of the farm’s 33-acres, nearly four acres are cultivated while the rest is preserved in three distinct ecosystems: coastal prairie, post-oak savannah, and pine barrens. In 1996, Conlon built a 5,000-square-foot straw-bale house and rain water harvesting system with a kitchen, gathering hall, and bunk rooms so that student groups could have extended visits on the land. In 2013, a Gathering Hall was completed with a commercial kitchen, reception hall, and bathhouse to accommodate weddings, conferences, and other special events. Student groups continue to visit Blackwood throughout the school year. During the summer Blackwood Nature Camp offers students another opportunity to spend time on the land and learn about ecology, growing and preparing food, and creating community. While Blackwood has always had an extensive kitchen garden, starting in 2012, it began expanding its growing capacity by erecting two high tunnels that help regulate temperatures in the winter. Blackwood still offers nature education but now focuses on resilient agriculture and the interconnectedness between a healthy natural environment and a productive agricultural system.

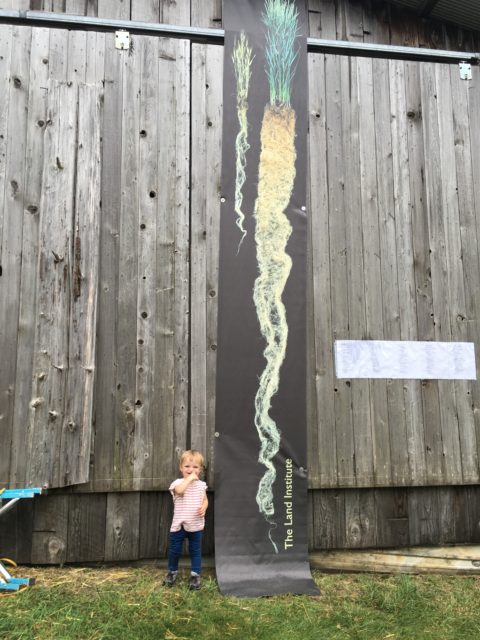

Present at both Blackwood and the Land Institute, too, are many elements of permanent agriculture, or permaculture, and I think this is why I kept seeing similarities. Since the 1990s, the Land Institute has chosen to pursue permaculture through a scientific inquiry into natural systems agriculture, which led them to developing perennial grains. Currently, they have developed a grain called Kernza to the point that it is now milled into flour and baked into bread — it is delicious, brown, hearty. Patagonia has recently started brewing beer, Long Root Ale, from the grain as well. The difference in root structures is the magic of perennials, allowing them to be more resilient to drought and disease and less dependent on chemical inputs. While in Kansas I thought Conlon, who was also at the festival, had to be thinking of ways to apply this knowledge to the prairie she is working on restoring. Surely she is thinking of all the young people she will teach so that they too know that magic.

As I watched my 18-month-old daughter tiptoeing in the rain just outside the festival’s lecture barn, I listened to Wendell Berry conjuring Aldo Leopold: “He knew that land destruction is easy: it requires only ignorance and violence. But to restore the land, and to conserve it, requires humanity in its highest completed sense.”

About a month after the festival, we drove up to Blackwood for a volunteer day. Becca Verm of Sown and Grown took us on a tour. She grows food here for local chefs and her Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) shareholders. She teaches students about farming and growing vegetables. She has plans to turn every third row into a habitat row full of perennial, native plants to support pollinators and beneficial insects. The idea is to create a healthy ecosystem above and below ground; this approach recognizes agriculture as a part of nature and figures out ways of working with natural systems instead of fighting against them. The work is physically taxing (especially in the heat) and challenges arise daily. But few things are as fundamentally important as growing food for sustenance, especially when it is healthy, local, resilient food. No perennial grains are yet available to grow in Houston’s climate, says Verm, but Conlon is in touch with the Land Institute and plans to continue collaborating with them.

After the tour, we dug in the soil for sweet potatoes, and we found a plethora of earth worms, small snakes, two families of mice, a few grubs. Around us flitted butterflies and other insects. I watched my daughter carrying the sweet potatoes to the wheelbarrow, proudly depositing them in the trough. At the end of the day, we shared a potluck. Some of the sweet potatoes were baked — they were earthy, filling, truly sweet. I looked around at the people who had come to volunteer: families and several of Becca’s friends. The work of building community, changing minds, creating a new agricultural model, is messy and slow, gritty and tiring. But also beautiful and full of days like this where strangers become friends, where we were able to participate (in a very small way) in a place that is restoring and conserving the land, where we were able to glimpse Leopold’s version of humanity.