In the aftermath of two “500-year” floods in the last three years and more recently a “1,000-year” flood following Hurricane Harvey, a two-book volume illustrating the work of the Risky Habit[at]: Dynamic Living on Buffalo Bayou studio, led by my colleague Peter Zweig at the University of Houston, reads more like prophecy than architectural research. Expanding upon the late University of Houston Professor Tom Colbert’s mapping of environmental issues confronting the Houston-Galveston Bay region, the studio proposed ten interventions along the 100-mile length of Buffalo Bayou that would defend against or mitigate Houston’s intense environment; their work received the Global Art Affairs Foundation (GAAF) award for best exhibition at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2014.

Over the course of three semesters, the Risky Habit[at] design studio students took a holistic look at Houston’s environmental challenges to reveal the interconnectedness between the city’s oil-driven economy, car-culture, unchecked sprawl, loosely-regulated petroleum refining industry, higher health incidents of cancer along specific sections of the bayou, and poor air and bayou water quality, as well as two aging and at-risk dams. According to Zweig, other risky habitats like Houston such as the Netherlands, New Orleans, and Argentina have utilized three strategies against flooding – evacuation, defense, and mitigation. The Risky Habit[at] studio investigated the strategies of defense and mitigation in their design proposals.

Rendering Dam City, which incorporates housing, rebuilt dams, and deeper Addicks and Barker reservoirs.

Rendering Dam City, which incorporates housing, rebuilt dams, and deeper Addicks and Barker reservoirs.

Dam City plan and section.

Dam City plan and section.

Beginning at the mouth of Buffalo Bayou with the Addicks and Barker Dams that straddle I-10 west of Houston, the Risky Habit[at] studio cut nine north-south sections at distinctive moments along the bayou including suburban communities to the west, downtown Houston, the East End, the Turning Basin, the Ship Channel, and the Chemical Corridor. With sustainability and resiliency built into all of the proposals, they operate at three distinct scales - the city, the building and the room.

At the scale of the city, public amenities are integrated with defensive infrastructures that bookend the bayou at the Addicks and Barker Dams to the west and the Shipping Channel to the east. In between, and at the in-between scale of the building, interventions are programmed to respond to their specific context with the goal of restoring the bayou. For example, in the East End, shipping containers are re-purposed on an island in the bayou as a self-contained prison that would capitalize on a rehabilitation program to help rehabilitate both the prisoners and the bayou system. At the smallest scale, that of a 20-foot room, the more traditional conception of façade is re-imagined as a spatial condition that mediates between the interior spaces and an often volatile external environment and the programming tends towards the recreational and whimsical. For example, in one project an inflatable façade morphs into different configurations to become a lantern for boaters, a swimming pavilion or a backdrop for performances just to name a few.

In the wake of Hurricane Harvey, the proposals at either end of the bayou are particularly compelling – Ship Gate on the eastern end of the bayou at the mouth of the Houston Shipping Channel and Dam City, a high-density housing intervention that would wrap around the eastern perimeter of Addicks Dam. Completed in the 1940s, the Addicks and Barker Dams were constructed after the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1938 in the wake of a 1935 flood that flooded downtown Houston and killed seven people. Today the reservoirs remain the only means to manage water flowing into the mouth of Buffalo Bayou. On August 27, 2017, after two days of heavy rainfall during which water was rising at a rate of 6 inches per hour, water flowed over the Addicks reservoir spillway for the first time in its 80-year history. In an effort to prevent more catastrophic failure of the reservoir and flooding, on August 28th, officials decided to release record amounts of water. Water was released from Addicks and flowed south under I-10 through an outlet leading to the bayou. The surrounding communities of Cinco Ranch southwest of Barker Reservoir and Bear Creek Village on the western edge of Addicks Reservoir were flooded, but without this controlled release, officials say, the damage to the surrounding area could have been far worse.

Although officials in the Harris County Flood Control District reject this notion, in many ways Houston is a victim of its own success. Laissez-faire regulations have made Houston a great place for businesses, and the lack of zoning and the acceptance of uncontrolled sprawl have made the Houston housing market one of the most affordable in the country. The combination of a relatively strong economy and affordable housing beckons more newcomers each year which leads to more expansion and more newcomers and so on. One of the casualties of this growth is the soil’s natural ability to drain off heavy rainfall. Houston’s soil (which is in large part clay) is among the least absorptive of all soil types, but tall prairie grasses that once grew before the area was settled by ranchers and farmers and then built up with housing, could have absorbed much of the run-off.

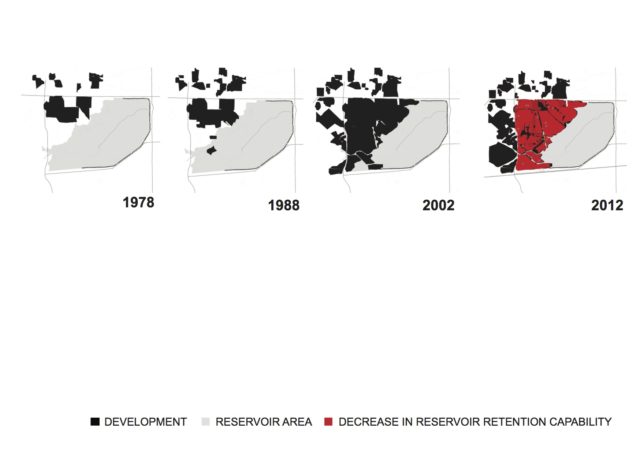

Looking at the project’s diagrams that describe the gradual encroachment of housing developments on the reservoir since the 1980s, one can easily understand the increasing pressure put on Barker Dam as land disappeared underneath house foundations and parking lots. By returning much of this developed land to prairie and compressing single family homes into a high density settlement with communal green space, Dam City becomes not just a new type of building, but a new way of life in Houston’s suburbs. Project designer Yoelki Amador proposed excavating a deeper bowl at the Barker Dam site and using the excavated earth to build up the bowl’s rim around the deepened reservoir. This built up rim would contain run-off waters within the bowl and lift a linear thirteen-mile housing development along its eastern, north and southern edges up above any potential threat of flooding.

The architecture consists of two interwoven paths that shift relative to each other based on changes in the program as they rotate around the rim. Retail shops and schools would be layered between housing above and parking below, but informed by solar orientation and views, the program changes as the system moves around the perimeter of the reservoir. The linear scheme would be connected by an electric transit system with garbage pickup at the lowest levels. The reservoir would always contain water giving residents a lake view year-round. The powerful perspectives of Dam City are created with an overlapping and interlocking structural system that occurs where vertical circulation towers connecting the levels overlap and would reinforce the dam’s strength, and garages below grade would help the system resist torque forces.

The studio considered the economic viability of the proposals as well. Replacing the dam as is would cost billions, but Dam City would be a private/public partnership with public funds coming in part from a consortium of public tax credits, TIRZ funds, and private real estate developers.

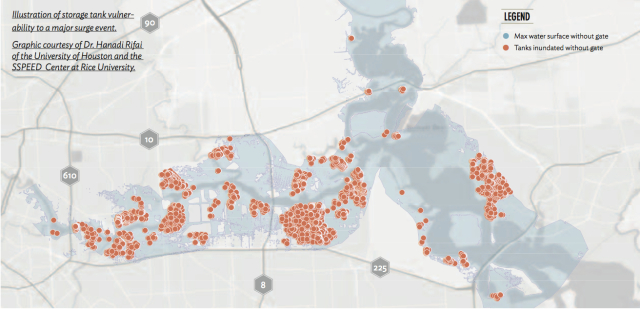

Chemical tanks at risk of flooding from hurricane surge.

Chemical tanks at risk of flooding from hurricane surge.

As devastating as Hurricane Harvey was for many Houstonians, in many ways Houston dodged yet another bullet. Working with SSPEED (Severe Storm Prediction, Education and Evacuation from Disasters) in the wake of Hurricanes Katrina and Ike, Professor Colbert warned that if the city suffered a direct hit to the Ship Channel, the collateral damage would be catastrophic. Colbert pointed to SSPEED studies that showed that “if Ike had hit the Shipping Channel directly rather than east of the Bolivar Roads, it would have generated a storm surge of 18 feet in the Houston Ship Channel and 15 feet on the western side of Galveston Bay.” The same report says that “although Hurricane Ike was only a Category 2 storm, it generated over $25 billion dollars in damage.” In the event of such a surge, thousands of lives would be in danger if people are not evacuated.

In addition to the loss of life and property, scholars like Hanadi Rifai have warned for years that Houston’s chemical storage tanks are vulnerable in the wake of high storm surge. A direct hit to the Shipping Channel would mean that the thousands of chemical storage tanks that flank both sides of the channel could become unmoored and crash into other floating debris or buckle in high winds and leak dangerous chemical toxins miles around. During Katrina, damaged chemical storage containers leaked several million gallons of oil into the surrounding landscape. The storm surge from Harvey was not as high as that of Katrina and Houston avoided the large scale chemical spills, though some storage tank leaks were reported. Zweig believes that the pollution to air, water and land created by the shutting down and restarting of chemical facilities before and after Harvey was greater than reported during the outbreak of Harvey: Texas allows the chemical storage industry to self-regulate and the industry often limits what they report regarding spills and toxic air.

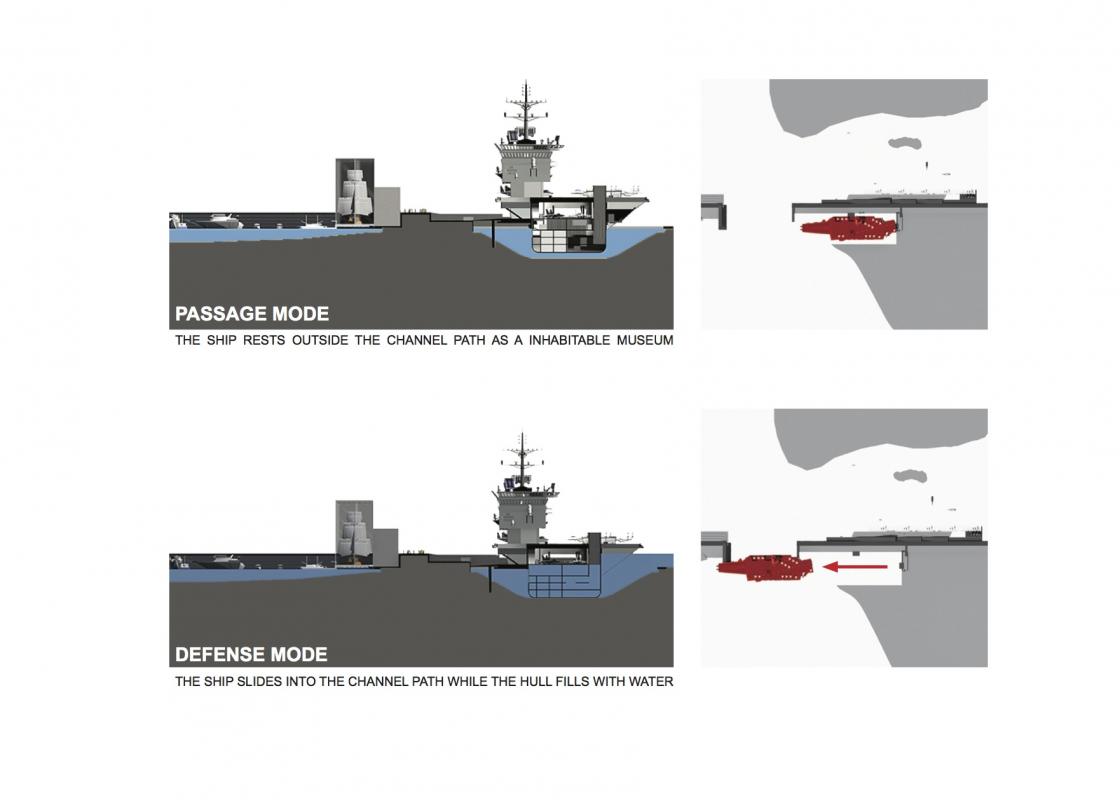

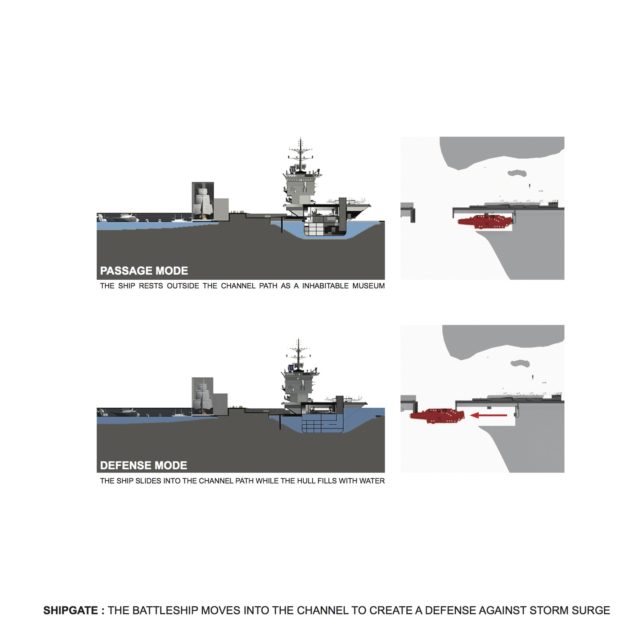

Shipgate section and plan.

Shipgate section and plan.

Shipgate rendering.

Shipgate rendering.

Risky Habitat’s proposed Ship-Gate, designed by Chase Stanley, would utilize a decommissioned military vessel that would be permanently docked at the mouth of the Shipping Channel. Until needed, its upper levels would house a museum much like the retired offshore rig, Ocean Star, in Galveston. In the event of a potential storm surge, the vessel, which would be docked perpendicular to one side of the Channel opening, would glide into the mouth and a valve would release, allowing water into the lower levels and partially sinking the ship. The vessel would remain there as a protective barrier until the surge threat passed. Since only the lower portions of the ship would be flooded, when the water drained from the hull, the vessel would return to use as a museum.

Ship-Gate was designed when the SSPEED center proposed the Centennial Gate (a floodgate that would be built mid-bay near the Fred Hartman Bridge) and Lone Star Coastal National Recreation Area, a non-structural surge mitigation proposal that would restore the natural habitat as protective surge barrier and provide a public amenity for locals and tourists alike. Colbert sought to highlight how this infrastructure could enhance public access to the bay and serve as a symbol for our community through a rendering that playfully positioned the Statue of Liberty at the site.

The SSPEED center has since revised its proposal. Researchers at Rice University, Texas A&M, and TU Delft have developed several proposals for gates and barriers. The broad concept of Ship-Gate and other recommendations for ecological barriers that serve multiple uses remain intact. The 2017 plan (H-GAPS) recognizes that no single intervention will protect the coastal system and has investigated “multiple lines of defense." As the specific approaches are evaluated, debated, and refined, the Risky Habitat proposal serves as a reminder to incorporate public access and delight into the final concept.

Houston was born from imagination — a narrative spun by the Allen family to attract investors to a non-existent, inland port. The settlers then set about making that narrative a reality. Two hundred years later, Houston is still a unique confluence of geography, people, and rugged individualism that resists more traditional models of urban planning. The Risky Habitat studio illustrates the same imaginative kind of thinking from which the city was born, but it remains to be seen if Houstonians have the will to once again build from imagination.

Sheryl Vazquez is a registered architect and lecturer at the University of Houston School of Architecture.

The UH Risky Habit[at] Studio is one component of a broader investigation conducted by the “Three Continents Studio: Living in Dynamic Equilibrium,” a year-long research partnership with Tulane University, the University of Buenos Aires, and Technical University, Delft. Developed under the auspices of the University of Houston Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and Design Dean Patricia Oliver and sponsored by the Gerald Hines Foundation, UPS and Thomas Printworks, the work of the Three Continents Studio was exhibited in three International Biennales in the 2013-14 academic year: Buenos Aires, Venice, and Rotterdam. The UH Three Continents Studio was led by professors Peter Zweig and the late Tom Colbert along with faculty advisors Michael Rotundi of RoTo architects and Kulapat Yantrassat of wHY architects. The Risky Habit[at] Studio was led by Peter Zweig with key student contributors: Jackson Fox, Lacey Richter, Sam Goulas, David Regone, and Wells Barber.