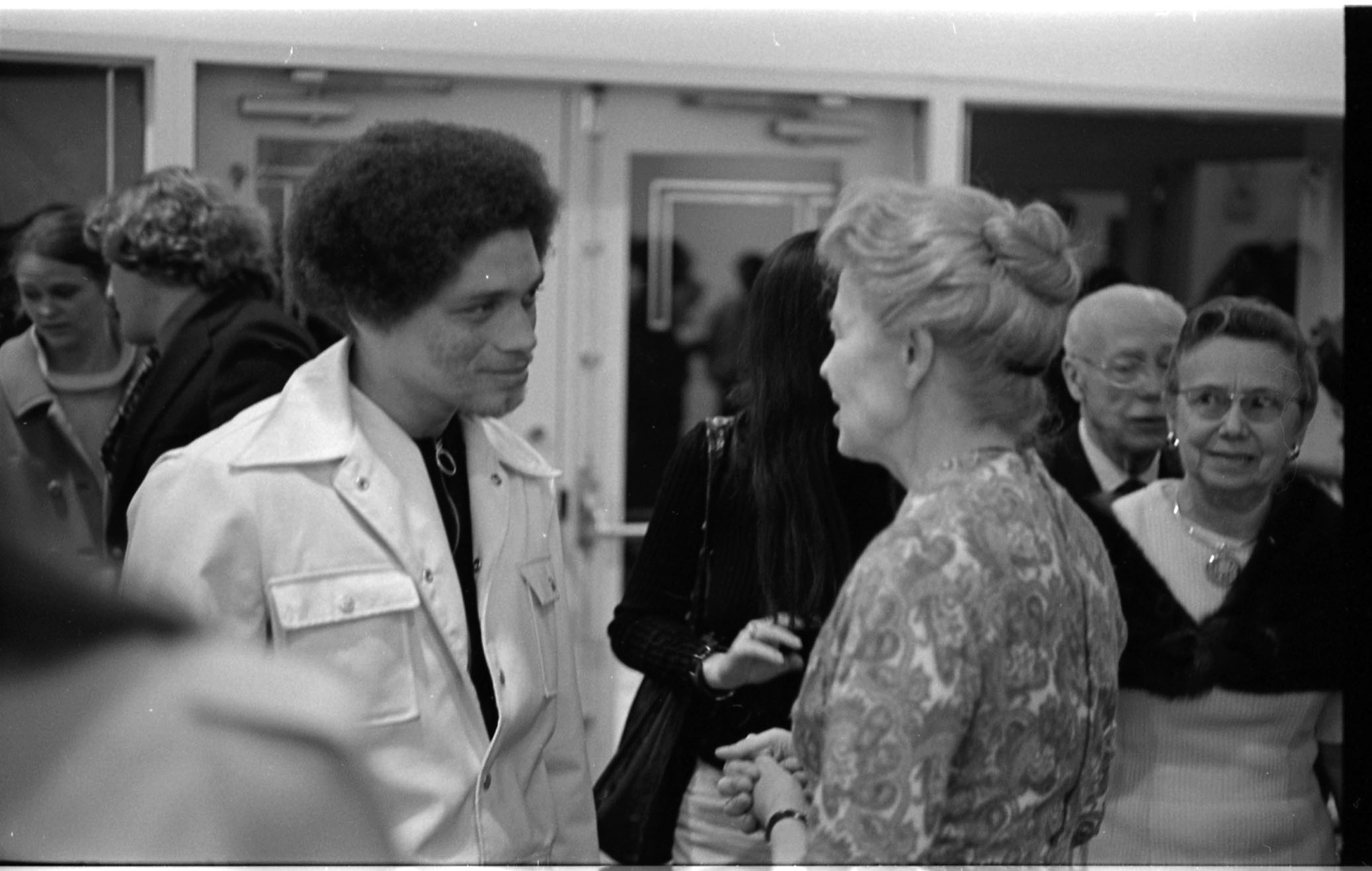

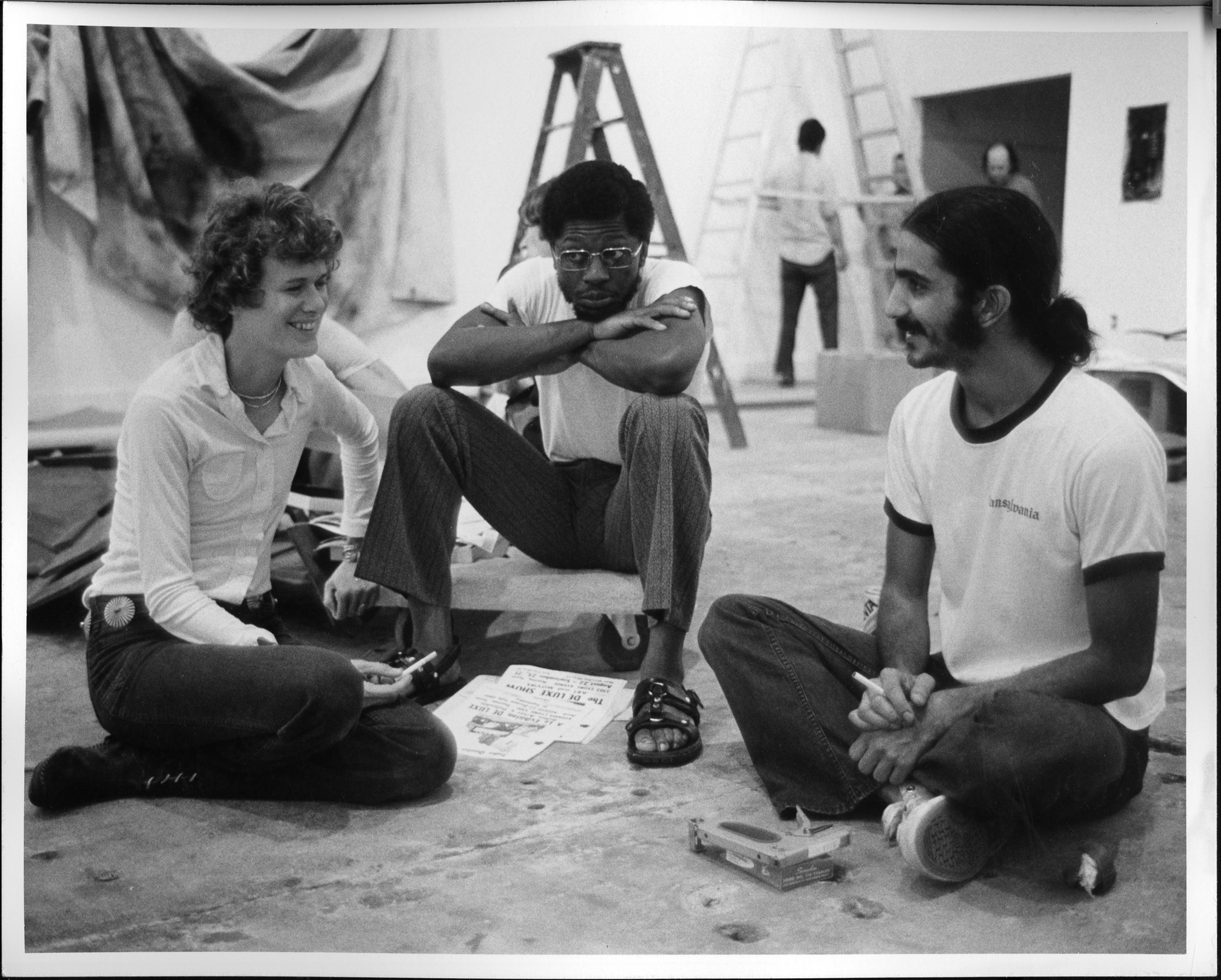

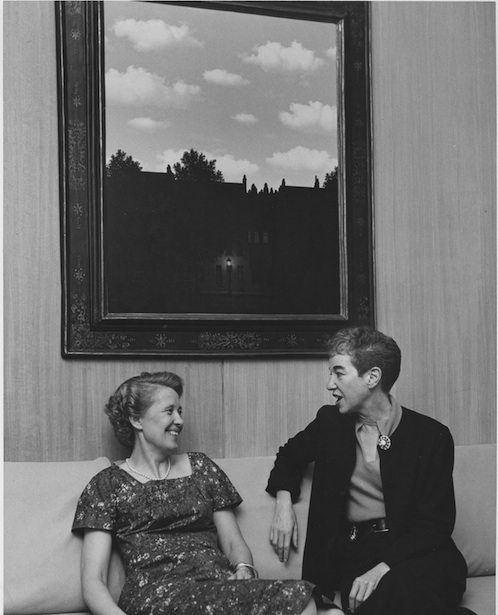

Dominique speaks with Mickey Leland at the opening of Some American History. All images from the Menil archives.

On Saturday, September 22, the Menil will celebrate its 25th anniversary with performances by the Kashmere Reunion Stage Band and the TSU Jazz Ensemblethat, as well as ice cream, cake, and a treasure hunt. All the activities are free and open to the public. At OffCite, we are marking the occasion by posting an article about the Menils' support of counterculture arts and politics before the Menil Collection was built. This piece about a remarkable period in Houston's history was contributed by Miah Arnold to Cite 82.

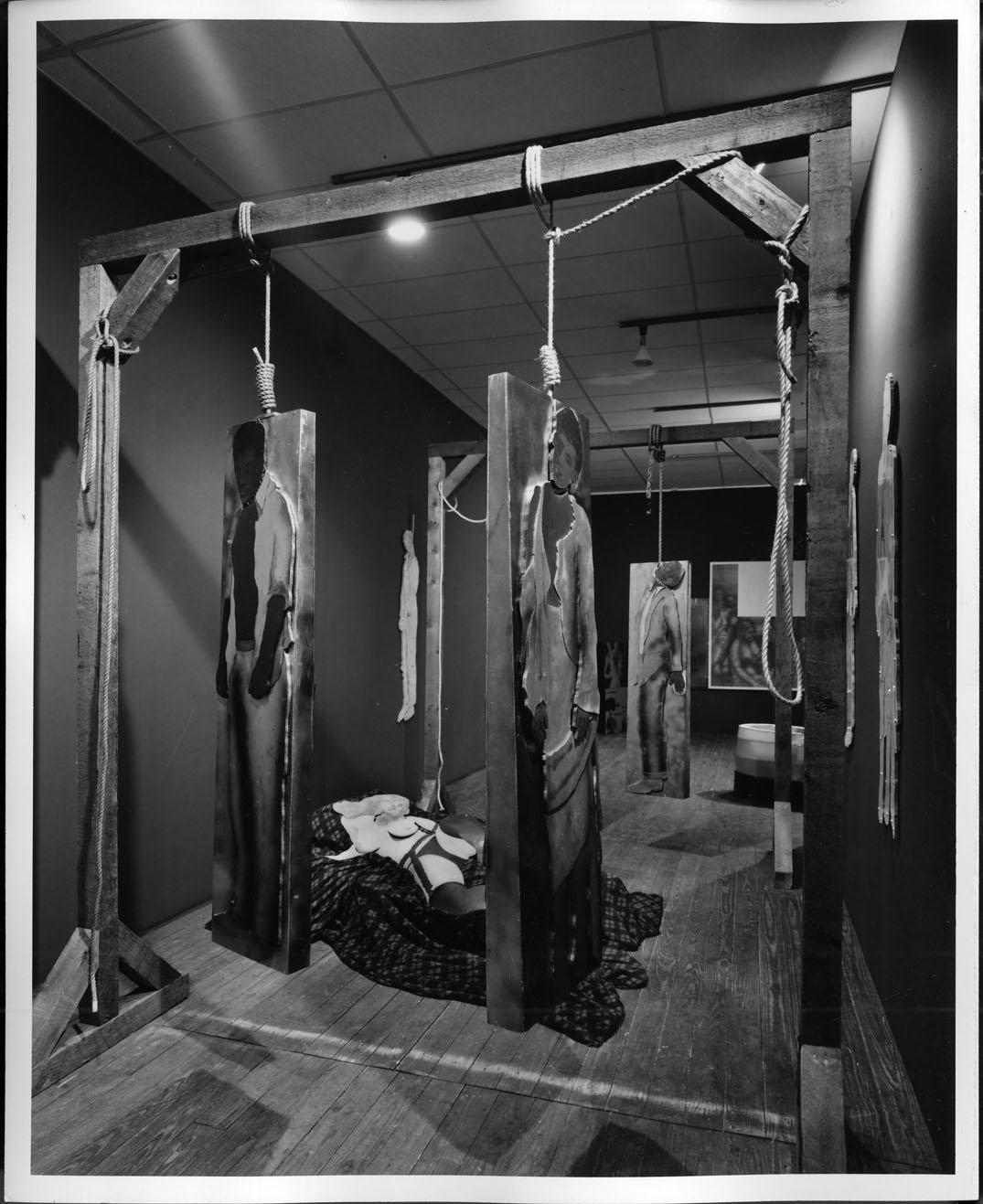

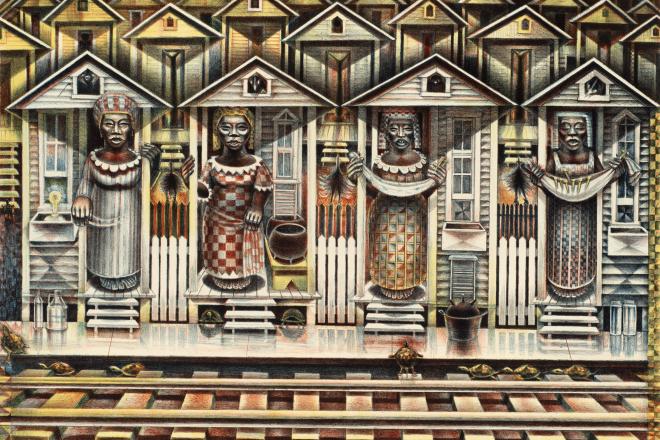

It was 1971 and Dominique de Menil was at it again. The show she had curated at the Rice Museum was called "Some American History," but it was not the kind of history many of Mrs. de Menil's River Oaks peers much appreciated. The most prominent piece—one by co-curator Larry Rivers—featured four life-size plywood cutouts of African American men dangling by nooses above a grotesquely rendered sculpture of a blond, buxom woman with her legs spread wide open. It was called "Lynching." As Jane Blaffer Owen relayed to Dominique Browning for an article in the April 1983 Texas Monthly, “The de Menils were sympathetic with the poor blacks, but so were we. I was a Southerner, but my family fought the KKK. My daddy’s family had slaves, but he was kind and wonderful to them. That show was terrible.”

Before they brushed their great gray wings across an otherwise ordinary neighborhood of bungalows in lower Montrose, before their place in Houston's history felt as ordained as the live oaks, and before Houstonians began trading stories about sightings of a thin and ethereal woman seated in front of her museum's great paintings, there was simply a couple: John and Dominique de Menil. A pair of émigrés who fled France after the Nazi invasion with their three small children in tow. A couple whose wealth, a prominent Houstonian once told Grace Glueck for a May 18, 1986, New York Times Magazine article, was “really peanuts,” when measured on the same scales as Houston’s old oil aristocracies. A couple whose story is as much about Houston’s coming of age during a time of social upheaval as it is about their pushing a cadre of visionaries to accomplish the extraordinary wherever an institution gave them the space and freedom to act. To recall just a few of the details of this story is as much an elegy as it is a celebration.

What happened around the de Menils in Houston will never be repeated.

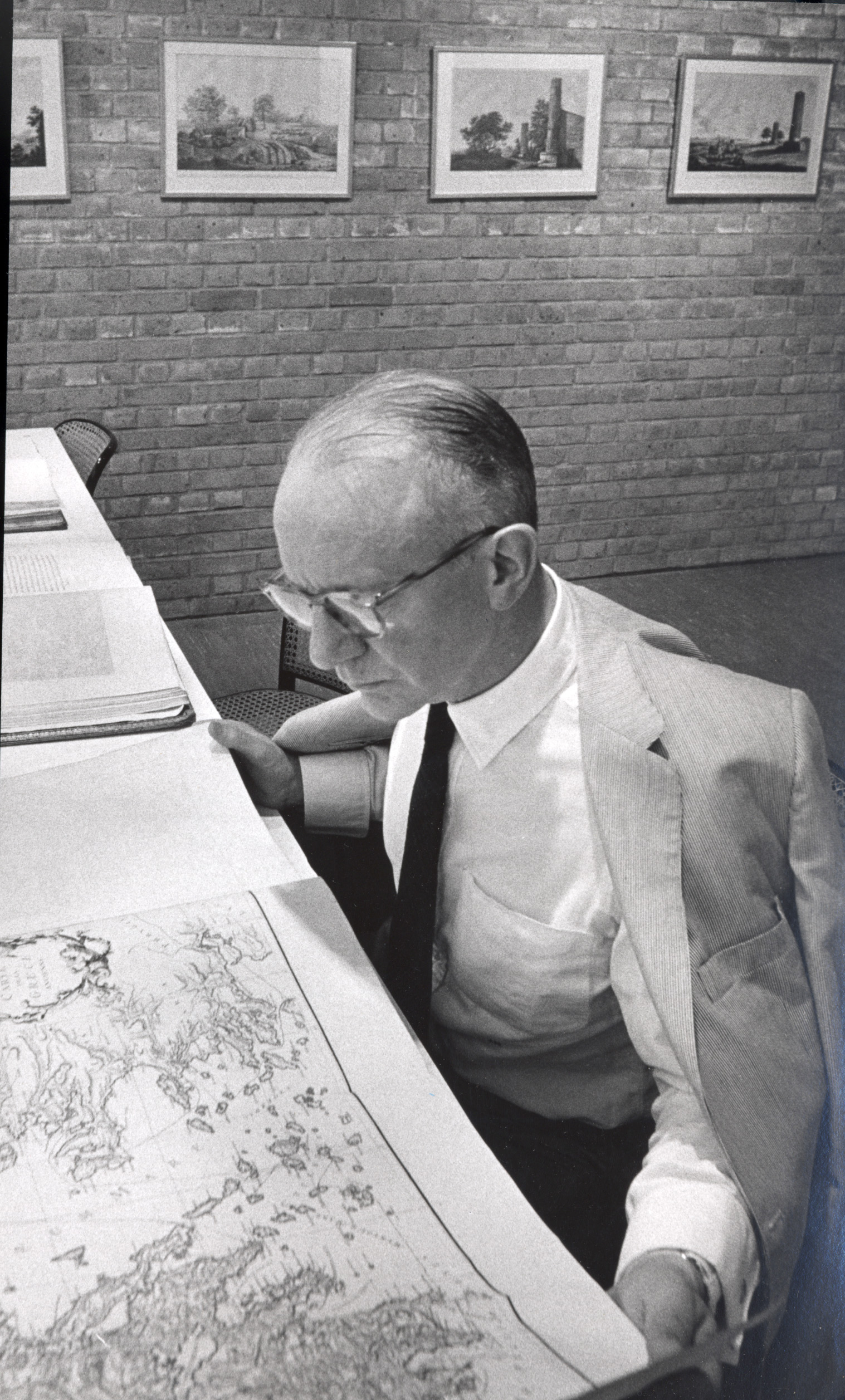

Dominique de Menil’s family’s money came from the textile industries. Her father, Conrad Schlumberger (pronounced “slumberjay”), was a geophysicist devoted to perfecting a device that could measure the separate frequencies of different kinds of ore when lowered into a hole; by the time Dominique was a young woman majoring in both mathematics and physics at the Sorbonne, her father’s invention could also detect oil deposits. This process became known as well-logging---or logging a Slumber Jay, as they still say on the oilfields---and it catapulted the family into enormous wealth.

John de Menil’s childhood was not so privileged. Napoleon had granted the de Menils a baronage for their military service, but by the early twentieth century, they were poor enough that when his two elder brothers were killed in World War I, John (née Jean) quit school to care for his parents and other siblings.

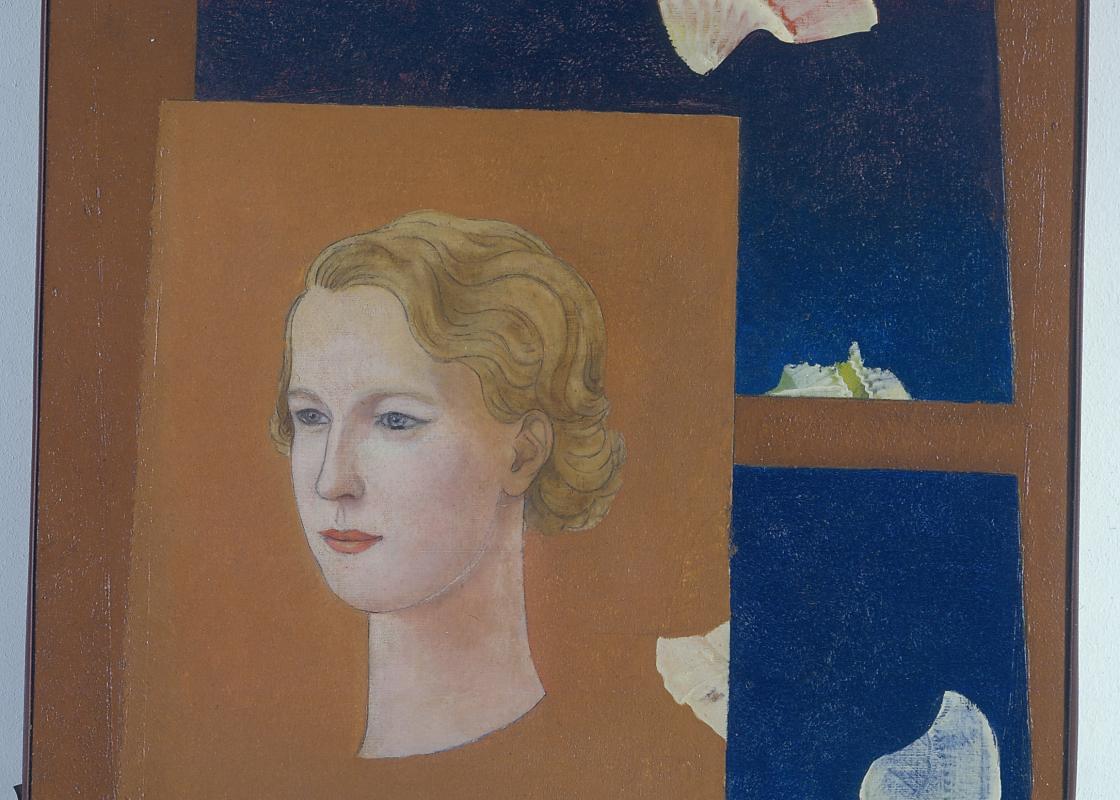

The two met at a Versailles party that both had dreaded attending, and they married in 1931. Dominique de Menil embarked on a path of self-discovery, first by converting from her family’s blend of atheism and Protestantism to John’s Catholicism, and soon after by joining her husband in purchasing their first works of modern art. At the suggestion of architect Pierre Barbe, they hired the young Max Ernst, renowned for painting birds, to decorate a wall in their apartment. Dominique is quoted in the Texas Monthly piece as saying that when the couple “saw the kinds of birds this fellow did, though, I hated them... We suggested he paint a portrait of me.” But the de Menils thought so little of Ernst’s painting, they left it wrapped in brown paper, atop a wardrobe, to weather the Nazi invasion without them.

From such tentative beginnings, their artistic tastes grew. In France they were influenced by Father Marie-Alain Couturier, a priest obsessed with updating Catholic chapels with modern art. More than a decade later, in 1945, John de Menil ran into Father Couturier on a business trip to New York and, on his advice, purchased a small Cézanne painting. After that, not only did the couple begin seriously collecting, but by 1952 their sensibilities had changed so much so that they sponsored Ernst’s first museum showing in the United States at the Contemporary Arts Association (CAA; now the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston), where they were volunteer curators.

As their interests in collecting burgeoned, they sought to include their friends and associates in Houston. For their academic and art world colleagues, they began a print club where prints by Robert Rauschenberg or Andy Warhol might be had for a couple hundred dollars or less. For their friends with pockets $10,000 deep, the de Menils began a collector’s circle. They amassed members’ money and used it to purchase a number of works from New York and European galleries. The art rotated among different members’ houses every three months. Jim Love explained to Sarah Reynolds in Houston Reflections: Art in the City, 1950s, 60s and 70s, if a family fell in love with something they could buy it from the group---and if they liked it not so much, it’s rumored, they could and did bury the piece deep in a closet for the duration of its tenure in their home.

Today a visit to the Menil Collection might convey an image of the de Menils as nothing more than rich art collectors. That may be what is most beguiling about the clapboard building Renzo Piano designed, which is monumental in a strangely modest and anti-monumental way. However, pieces like René Magritte’s the Rape, with its breasts for eyes and vulva for a mouth soon begin unraveling the museum’s subversive history.

If her father Conrad Schlumberger had learned to divine oil, Dominique and John de Menil divined artists, provocateurs, and visionaries. One of the most influential figures in Dominique’s life was a woman named Jermayne MacAgy---today Dominique rests between John and Jermayne in the Forest Park Lawndale Cemetery. In 1952 the CAA invited curator Douglas MacAgy to assess the organization, but he was too ill to travel and sent instead his wife. Jermayne recommended the CAA board hire a full-time director. They were so impressed by her that they hired her for the position in 1955.

MacAgy was already the art world’s answer to Rosie the Riveter. In 1941 she had been working at the Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco when the museum director left to join the Navy, and she took over as acting director. A 1983 brochure on an exhibit of her gifts to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art described MacAgy as “a wonderful comet... [full of] vim and vigor and gusto,” and as a woman “given to indelicate language and bursts of temper.” She was also, by all accounts, a genius curator. “There is probably no museum in the United States where the art of displaying art has been developed to so fine a pitch,” a San Francisco Chronicle reporter once wrote of the Legion under her tenure.

It wasn’t just that she showed the work of vanguard artists like Mark Rothko, Georgia O’Keefe, Clyfford Still, and Yves Tanguy. Her exhibitions were explorations that often juxtaposed similarly themed pieces from different moments in art history. By defamiliarizing objects, removing them from their expected places in a museum, she allowed patrons to see them anew. In her four years at the CAA, and on a budget of less than $20,000, MacAgy put on 29 shows. She is most known for Totems Not Taboo, a 1959 exhibition staged in Cullinan Hall, the new Ludwig Mies van der Rohe-designed wing of The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The two-story gallery is notoriously inhospitable to most exhibitions. According to many people in Houston’s art scene, MacAgy is one of only two people who have ever successfully filled the space (the other is James Johnson Sweeney, another great mind brought to Houston by the de Menils in the sixties).

Despite these successes, the CAA cited financial strains and chose not to renew MacAgy’s contract in 1959. Since the de Menils would gladly have funded her salary, it was clear the board was uncomfortable with the amount of influence the de Menils themselves were exerting upon the museum---a complaint that would become common to other institutions the couple became involved with.

The de Menils later saw their difficulties with the CAA as a happy accident. Years earlier, the Basilian Fathers at the University of St. Thomas had asked John de Menil’s advice on an architect for their campus. According to Karl Kilian, “a typical John said, ‘I’ll help you, but I’m going to make the rules. I will give you a list of architects you ought to consider, and I will pay to have some initial sketches done, but you have to agree to use one of those architects.’” The Fathers chose Philip Johnson’s design, based on Thomas Jefferson’s plans for the University of Virginia. So when the CAA grew displeased with the de Menils, they withdrew financial support and offered it---and MacAgy’s talents---to St. Thomas.

In those days, what is now the business building at St. Thomas had a giant Alexander Calder mobile hanging in the foyer, and the university hosted friends of the de Menils from throughout the world, including visiting artists like René Magritte and Rothko. The art department soon filled with promising young art historians like Karl Kilian, Fred Hughes, and Helen Fosdick---students the de Menils liked to “trot out” for guests. It was not unusual, Kilian says, to be invited out for cocktails with [Marcel] Duchamp or dinners with [Roberto] Matta.

MacAgy was the center of this world. She taught a small generation of students---as well as Dominique de Menil---about art with a method that was as playful and rigorous as her exhibitions. Fosdick remembers MacAgy requiring her to be able to name the different paintings in the different halls of European museums as if on a sort of virtual walking tour, or MacAgy would describe an obscure painting “someplace in Florence, and I would have to find it.”

MacAgy made it a joy to learn about art and had at her disposal a large chunk of the de Menils’s art collection, which was then called the Young Teaching Collection. According to Fosdick, “We always had [the art] in our hands, and it was a very great thing.” Indeed, the Young Teaching Collection was a radical enough idea in 1969 that it was lauded by Art Journal. (Kilian says he still can’t get used to not touching the art on display at the Menil, and Fosdick only half-jokes that on occasion she can’t refrain from touching the sculptures.)

Dominique de Menil and Jermayne MacAgy.

While teaching, MacAgy continued with her wondrous exhibitions, which often scandalized parts of Houston society even when the art was in no way obviously offensive. At an exhibition MacAgy organized for the opening of Philip Johnson’s gallery at St. Thomas, a member of the John Birch Society claimed to see a hammer and sickle in a painting by Mark Tobey. The Basilian Fathers strained to defend the radical curator who would later become the university’s art teacher, and the de Menils themselves were threatened with a possible Congressional investigation for communist sympathies because of just these sorts of happenings.

“Art is sometimes scary to people because they don’t understand it,” Fosdick muses when asked about those times. “But it’s one of the greatest energies mankind can give to the world. It’s always there to give back freely just by our experiencing it.”

MacAgy was 50 years old in 1964 when she died of diabetic shock, devastating her admirers, especially Dominique and John de Menil. Grieving, Dominique helped finish MacAgy’s last exhibition, prophetically entitled Out of This World. Then, emboldened by what her friend had taught her about how to conceive and install exhibitions, Dominique took over as chair of the art department at St. Thomas. William Camfield had been hired by MacAgy months before her death to teach art history to the students. Eventually the faculty would include photographer Geoff Winningham and activist/documentary filmmaker James Blue. The movies screened during this period were controversial enough that students at least once---during the screening of Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures---locked the theater doors as soon as all the moviegoers arrived, fearing a police disturbance.

In 1967 the ecumenical vision of the de Menils began to clash with the conservatism of the Catholic university. When they attempted to broaden the university’s base by bringing lay people to its board, the Basilian Fathers resisted. So John and Dominique de Menil decided to separate from St. Thomas, retrieving the Teaching Collection in exchange for real estate; they then took their art collection and all the people they had hired for the art department to Rice University. They founded the Media Center at Rice, and artists like Jean-Luc Godard, Andy Warhol, and Roberto Rossellini screened films there.

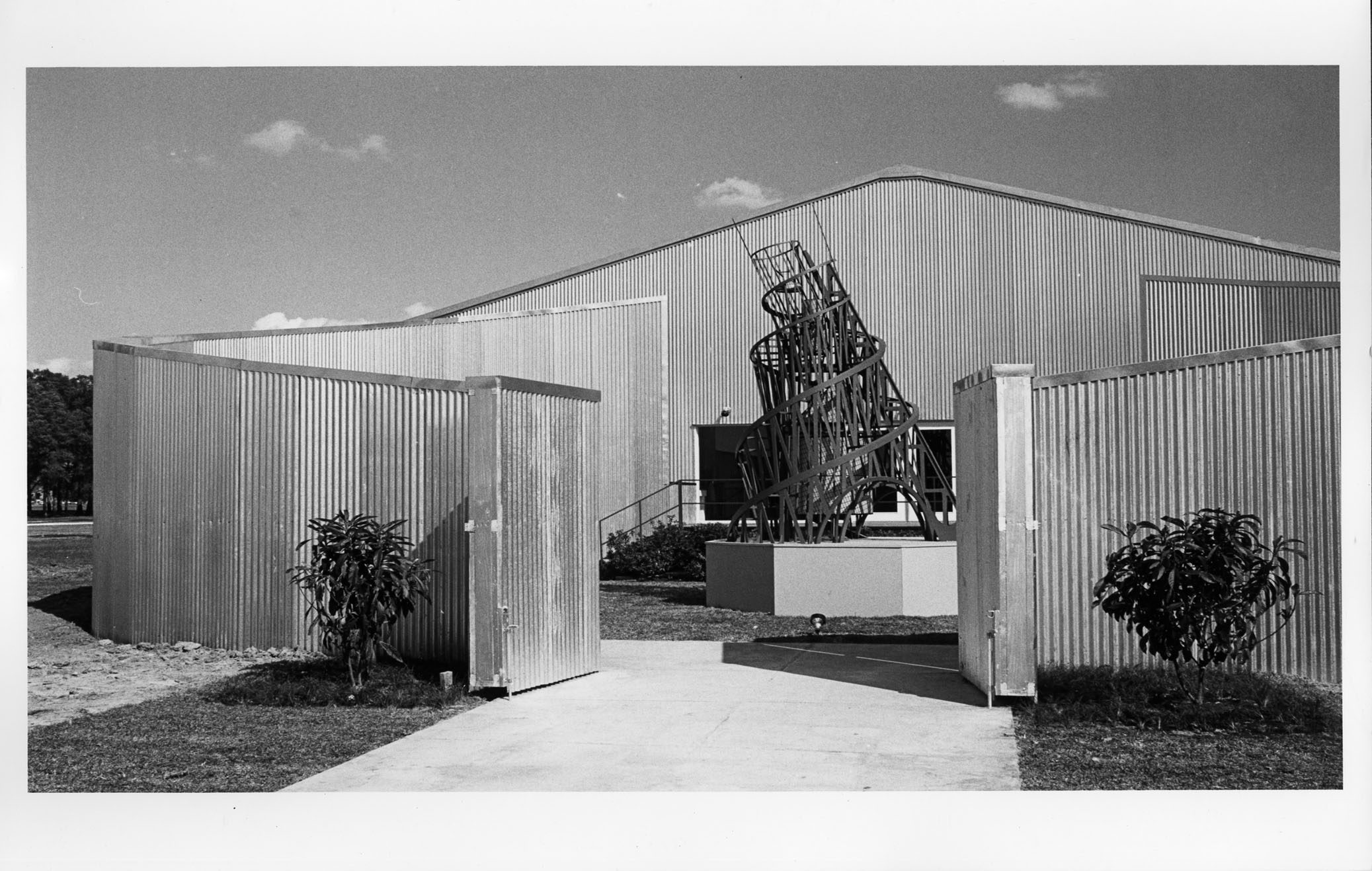

The de Menils’s arrival at Rice coincided with the opening of The Machine Show, an important exhibition from the Museum of Modern Art they had scheduled to show in Houston. With no time to construct a proper building for it, they built two “temporary” structures out of corrugated metal that today house the Rice Media Center and the Continuing Studies Program.

Even though John de Menil was a hard-nosed capitalist, a formal man whose idea of relaxation on Sundays, recalls Kilian, was to rest the jacket of the seersucker suit he wore every day of the week over his shoulders instead of putting it completely on, he was also an Old World radical. His own upbringing and brush with European fascism hardened his resolve, and the de Menils spent a great deal of energy, money, and time working against the staunch racism they encountered when they moved to Houston. Thus, their ambitions were not restricted to the art world, and their work in Houston did not reside entirely within existing institutions.

Just as they took an interest in young art students, they sought out and supported up-and-coming young African-Americans in a number of professions. They also bankrolled politicians with social agendas they believed in. In the case of Mickey Leland, who became the first African American Congressman from Texas, they did both.

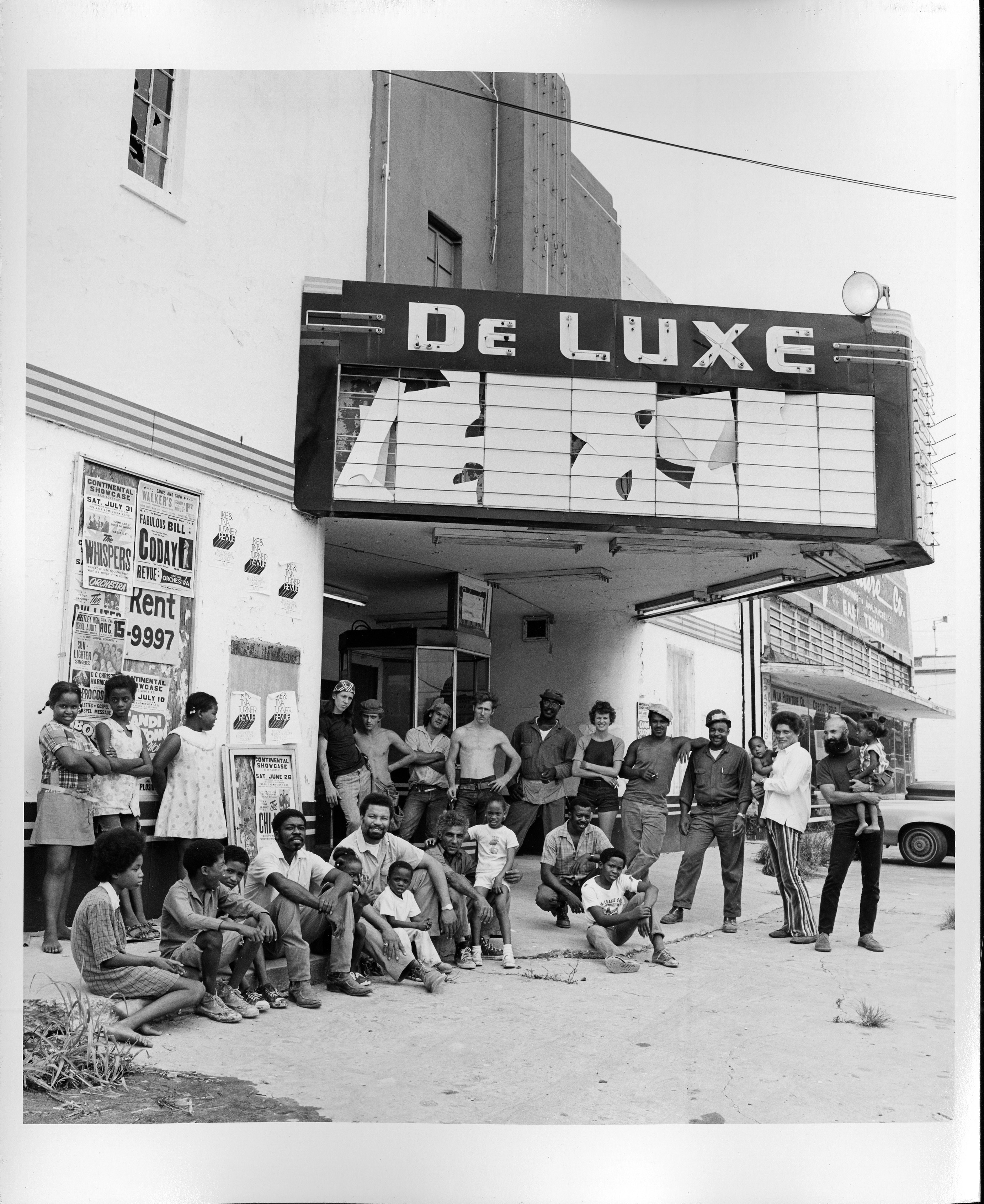

Their association with the young activist began in 1969. The de Menils had ambitions to bring the modern art that was finally taking hold in Montrose into communities that ordinarily had little contact with it. They wanted to remodel the crumbling but once grand De Luxe Theatre in the Fifth Ward as a space for art. They contacted Leland to act as liaison between community leaders and themselves and hired artist Peter Bradley in 1971 to curate a show of 19 contemporary painters and sculptors, including Michael Steiner, Richard Hunt, Larry Poons, and Kenneth Noland---the first racially integrated exhibition of contemporary art in the country. The wildly popular show ran for a few months, and afterwards the site hosted a large portion of the de Menil African art collection.

Though the Black Arts Gallery at the De Luxe Theatre closed just a couple of years later, the relationship between John de Menil and Mickey Leland grew. John acted as the young man’s patron, introducing him to well-connected people from throughout the world and supporting his political ambitions. “I went to breakfast, lunch, and dinner at their house,” Leland once recalled. “He wanted me exposed to every aspect of their life that would give me a chance to do things for my community. They helped make a black militant who hated white people into a humanitarian.”

Once John de Menil received a call from a raging man accusing him of being a communist for supporting Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. “Listen, my friend,” he gamely replied when the fellow had calmed down, “why don’t you come to my house for a drink? Then you can see how a communist lives.”

For the general public today, the de Menil name signifies a soothing campus of art museums, galleries, and chapels. The gray clapboards of the Menil Collection building seem as inevitably a part of Houston as the odd marriage of progressivism and oil-driven capitalism that served to define the city. When interviewed in March 2010, Kilian gestured to the clearly de Menil-inspired elements in his house---from the modern furniture in his living room to the abstract paintings and tribal masks on his walls---and mused, “I didn’t even notice it all becoming precious in my life.” This sentiment seems right for the city of Houston itself.

In 1991, on the 20th anniversary of the Rothko Chapel, President Jimmy Carter and Dominique de Menil presented the Carter–Menil Human Rights Prize of $100,000 to the university that had been home to the six Salvadoran Jesuits murdered in 1989 for championing human rights. Nelson Mandela, just released from more than two decades of political imprisonment, was the keynote speaker. To hold the hundreds who wanted to attend, a large tent was constructed next to the Chapel with seating, a stage, and large screen for projecting a live stream from the Chapel.

The tent’s enthusiasm for the event was carnival-like in comparison to the silence of the crowd in the Chapel’s interior. When the program was over President Carter and Bishop Tutu came to greet the tent crowd who clapped and greeted them as they walked to the edge of the stage and started shaking hands. A minute later, however, the crowd erupted into a cheering, standing ovation that confused the men until they turned around and realized what had happened: Dominique de Menil had stepped out into the crowd’s view. The crowd that would greet two of the world’s most revered heroes with polite applause could not hold back for their own Dominique, Houston’s patron saint of underdogs and artists. The men brought her to center stage and the crowd cheered more.

To the people who had known Dominique and John de Menil since the 1940s, this moment was striking in more than the obvious way: it signaled that five decades after making Houston their home, Houston had finally fully claimed the de Menils as its own.