With all the attention this fall paid to the preservation of the Astrodome, there is an opportunity to recall the other sports palace that put Houston on the map a decade earlier: Rice Stadium. Plans for remodeling the stadium have been discussed since 2011, but they are largely out of the headlines because no public funds are involved. Most of the attention has been on the narrow programmatic needs of the Rice Athletic Department, despite the importance of the project to the quality of life and economic well-being of Houston. The historic preservation and architectural issues might be even more significant than those at the Dome.

Some background: In the fall of 1949, while on their way to their fourth SWC Championship in 15 years, Rice Institute decided to build a new football stadium. Since the 1930s, Rice football had been the biggest game in town. All-Americans like Weldon Humble and Froggie Williams were local heroes. Victories over powers like Texas, Texas A&M, and Louisiana State were expected and often delivered by the Owls. Crowds were overflowing the old Rice Stadium at the corner of Main and University.

Coach Jess Neely and trustees George R. Brown and Herbert Allen led the way. Starting at 10:00 p.m. on an October Sunday night, they assembled an all-Rice team including architects Herman Lloyd, Bill Morgan, and Milton McGinty and engineers Walter Moore and Mason Lockwood. The team was charged with designing the stadium and getting it open in just 11 months. This was an incredible challenge, considering that more than 50 years later and with the advantage of advanced computer technology, it took three years to design and build Reliant Stadium. (The Astrodome took four.) Brown volunteered to construct the stadium at cost through his construction firm, Brown and Root, and assigned his top superintendent, Frank Kuich, to the task.

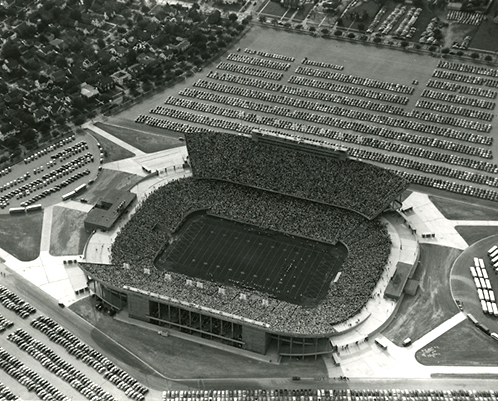

While Kuich mobilized, the design team and Neely researched the best stadiums around the world, including the Cotton Bowl and the Berlin Olympic Stadium. The conceptual decision was made by the architects to excavate the lower bowl, top it with a continuous open concourse, and float the upper decks above it all — a concept later adapted to the Dome and a number of other modern sports venues. Crucial to the concept was providing open and easy access to all seats as well as to a covered platform for concessions, band parades, and pre-game pep rallies. Neely insisted that the stadium contain no track — common in stadiums of that era — and the result was, in spite of the 70,000 seats, a sense of intimacy and spectator involvement in the game unmatched in any of the round, multisport arenas that followed in the ‘60s. The architects and engineers completed the design with the slender columns and elegantly curved upper decks that create the signature form of the structure.

With little more than that idea in mind, in early 1950 Kuich started the excavation while construction plans were still being completed, drawn by hand with engineering calculations performed on a slide rule. Work proceeded around the clock with additional drawings delivered to the job site daily. Kuich invented an innovative forming system for the upper decks; it was situated on rails along the concourse that allowed the forms to be moved and a section placed every few days. When asked whether his team would complete the stadium in time for the opener with Santa Clara on September 30, Brown asked whether it was a night or a day game. The scoreboard was installed that afternoon, in fact, while an army of recruits including students bolted down the last seats. That night, before a full house, Rice beat Santa Clara 27-6 and a new era in Houston sports was launched.

During the next 15 years, Rice Stadium was the most famous football stadium in America. It received numerous architectural honors and hosted regular sell-outs of 72,000 or more fans. Some of the most memorable games included the 1956 7-6 victory over top-ranked A&M, led by Bear Bryant and Heisman Trophy winner John David Crow. Major powers and their stars came to town, including Wisconsin, with Alan (The Horse) Ameche, and Army, with their All-American Lonesome End, Pete Dawkins. UT experienced many misadventures there in the '50s, leading new coach Darrell Royal to comment that he thought the architects had included a tilt mechanism in the design that had his 'Horns always playing uphill.

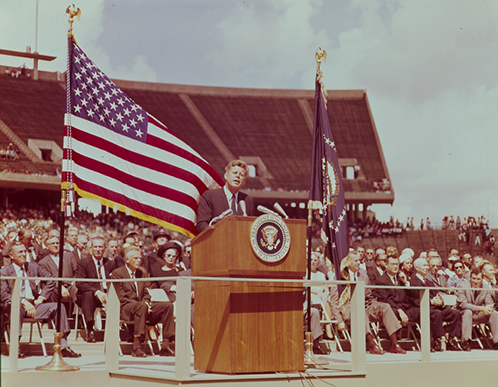

And it was not only football. Rice Stadium was the forum for all big events in Houston, including the 1961 speech when President Kennedy announced the goal of landing a man on the moon before the end of the decade. It was the site of major rock concerts including Pink Floyd, George Strait, and the Eagles. It hosted the 1972 Super Bowl between the Minnesota Vikings and the Miami Dolphins, concluding the only perfect season in NFL history.

Times have changed, and Rice no longer plays in the big leagues of college football. UT, A&M and the NFL no longer visit. Starting in the ‘60s, the Owls faced stiff competition, not only on the field, but also from the Astrodome and Houston’s professional teams, the Astros, Oilers, and Texans. In a last hurrah in 1963 to keep Rice Stadium in the big time, Bud Adams commissioned the architects to study the feasibility of a large canopy, ostensibly to make the stadium a permanent home for the Oilers. More likely was the study’s use as leverage in Adams’ negotiations with Harris County about rent for the Astrodome. It worked — both the canopy and the leverage. The Oilers found an affordable home in the Dome and Adams saved a bunch of money, but media attention and fans followed him away from Rice. Today, crowds seldom reach 30,000, and the venue is more popular with alums and neighborhood families with children who find the stadium a perfect place to pass a sunny autumn afternoon, eating reasonably priced hot dogs and reminiscing about the glory days.

Unlike the Astrodome, it would be relatively easy and inexpensive to repurpose Rice Stadium for this new era while keeping its iconic architectural status. There is no asbestos and no air-conditioning to remove. Imagine a lower bowl with far fewer but more comfortable sideline seats and club boxes for the alumni faithful. Grassy terraces in the end zones would provide a place for children to chase footballs from extra points and for families and students to picnic and sunbathe as they do on the baseball hill. The encircling concourse would remain intact, providing covered areas for alumni BBQs, student pep rallies, and roving fans to walk and watch the action while keeping an eye on their kids. The upper deck might become a pavilion with unreserved seats at bargain prices, attracting neighbors and fans who cannot afford a $200 family outing at Reliant. Immediately surrounding the stadium could be a small urban park with hike and bike trails as an amenity for the neighborhood. In this new and relaxed mode, the stadium would provide a more suitable venue for other events like concerts, youth soccer, and high school football — all consistent with Rice’s oft-stated mission to be a vital part of the city’s culture.

Some of the proposed schemes to remodel the stadium severely compromise this vision. Removing the south end zone, for instance, would destroy the logic and form of the original design, as would a new appendage to the east concourse. We can do better than that. A modern enlarged football facility could easily be accommodated by removing and rebuilding the present array of coaches offices, lockers, and weight rooms that have been added piecemeal to the east concourse and the south end zone without destroying the architectural continuity of the concourse and integrity of the bowl.

Like the Astrodome, Rice Stadium is a major piece of Houston’s history, widely published and recognized as one of the best mid-century modern buildings in the world. In 1952, it received an Honor Award for Design Excellence from the Texas Society of Architects. In 1979, it received the AIA 25-Year Award for Extended Use. It is located in one of the most vibrant and visible neighborhoods in the city, adjacent to the Museum District and the Medical Center where other architectural icons abound. It is time to stop tearing down or disfiguring our distinguished landmarks, revered by generations of Houstonians. Rejuvenating this historic, architecturally important stadium in a way that honors its past is not just a Rice issue, but a Houston issue.

by John M. (Jack) McGinty, FAIA

More >>>

Read a 2011 Rice University press release on the stadium renovation.