Creation and destruction of the Prudential Building

The new issue of Cite (89) features an eye-opening overview of the Texas Medical Center's history from 1945 to present by Ben Koush. The article analyzes the master plans that have, to varying degrees of success, sought to guide its growth. Crammed in the inner margin of the article were Koush's notes on the actual buildings in a "city of medicine." Here we give the photographs some more room to breath. Enjoy, and get a copy of the issue for more of this kind of insight at Houston independent booksellers like the MFA,H, Brazos, Domy, CAMH, and the Menil.

The Texas Medical Center, perhaps Houston's greatest institutional campus of the postwar era, is intriguing if for no other reason than that it has grown so large. According to its own statistics, by the end of 2011 it was expected to surpass downtown Houston in square footage and become the equivalent of the seventh largest central business district in the country. Since the Texas Medical Center includes both a large number of buildings and the impressive infrastructure to support them, the growth of this “city of medicine” can be seen as a representation of modern Houston in a condensed form.

1925 — A Charitable Beginning

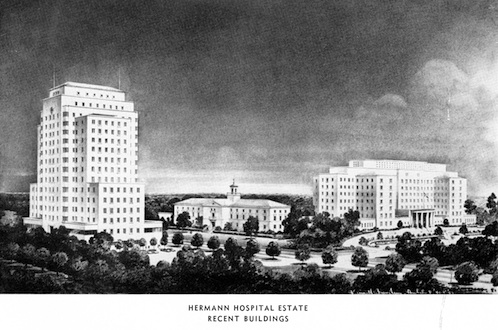

Hermann Hospital, Berlin & Swern (Chicago), Alfred C. Finn. 6411 Fannin Street.

Parklane Apartments., F. Talbott Wilson and S. I. Morris. 1700 Hermann Drive.

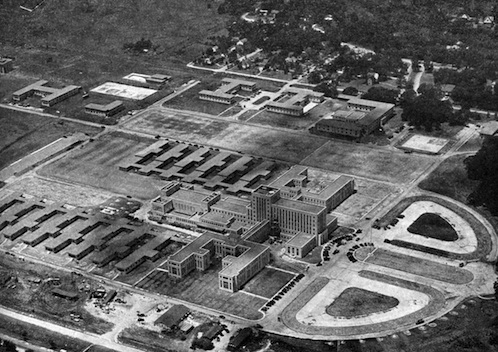

United States Naval Hospital, Finn, Cummins & Taylor. 2002 Holcombe Boulevard.

United States Naval Hospital aerial.

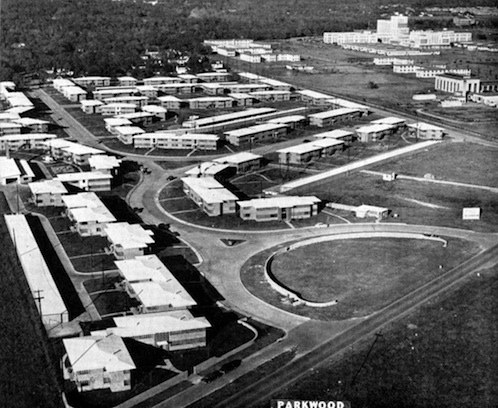

Parkwood Apartments, Raymond Brogniez. 7331 Staffordshire Street.

Hermann Hospital additions.6411 Fannin Street.

Shamrock Hotel. rendering, Wyatt C Hedrick. Holcombe Boulevard & Main Boulevard.

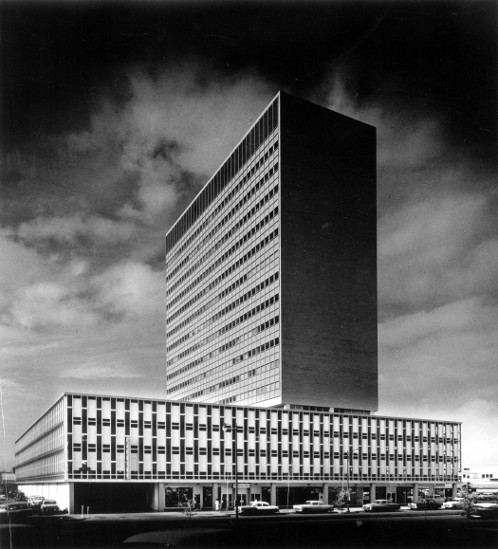

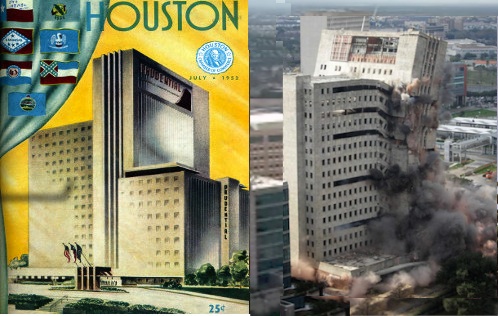

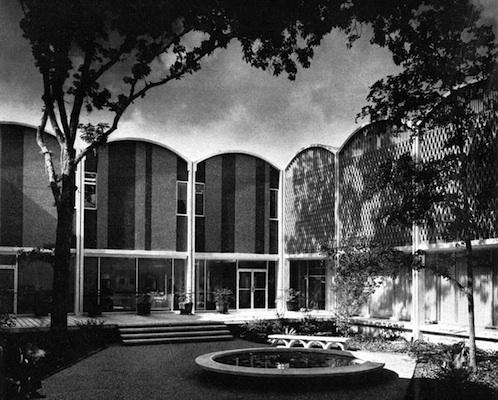

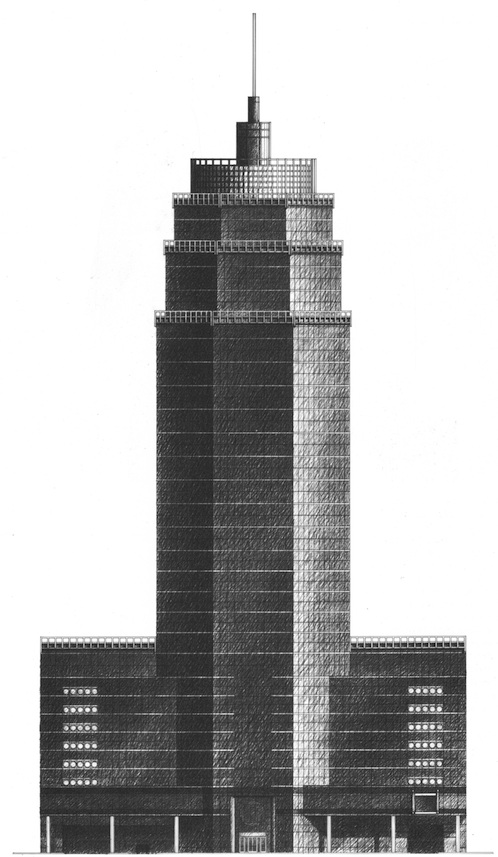

Prudential Building, Kenneth Franzheim. 1100 Holcombe Boulevard.

Gus S. and Lyndall F. Wortham Park fountain, John Burgee.

Hermann Hospital (1925) was the first medical building in the vicinity of what would later become the Texas Medical Center. It was built with funds donated by George H. Hermann as a charity hospital for the Houston’s indigent. This role was later taken up by Ben Taub Hospital, whose first iteration was built in the 1960s. Today the original, remaining portion of Hermann Hospital, now dubbed the Cullen Pavilion, is literally entombed by a giant-scaled wrap-around addition designed by WHR Architects (2002).

The Parklane Apartments designed by F. Talbott Wilson and S. I. Morris (1940, demolished) were Houston’s grandest FHA-sponsored garden apartment complex of the New Deal Era. Terrence Doody contributed a wonderful essay about living in the complex in the Summer 1999 issue of Cite (45). He writes, "[A]t the time, Hermann Drive stopped at Jackson Avenue and the goll course had not yet been developed. Because the Parklane was built in the days before central air conditioning became com- mon, the siting ot the buildings ior cross ventilation and the role of the trees in keeping things cool were very important. This was a garden apartment made tor the shade."

1940s — Well-Behaved "Forbears"

The first master plan for the Texas Medical Center by Herbert A. Kipp called for buildings on a scale and style similar to the Rice University campus. The recommendations were followed at first.

The Baylor College of Medicine (1947) was the first new building completed after the inauguration of the Texas Medical Center. It still functions in its original use. The bas-relief sculptural panels on the front elevation were executed by Edward Z. Galea. The chunky porte-cochere projecting into the motor court along with the round fountain was a later addition by Ray Bailey Architects (1982).

The giant United States Naval Hospital designed by Finn, Cummins & Taylor (1946) located on a 118-acre site southeast of the Texas Medical Center as well, as the Rice Institute, were also considered as being in part of its orbit, although not officially members. The naval hospital, which was designated as the VA Hospital in 1948, was the original teaching hospital for the Baylor Medical School.

It was demolished in the 1980s and replaced by the current VA Hospital building (1991) designed by 3D/International and Stone Marracini & Patterson (San Francisco). The newer building is like a gigantic geometrically complex, interlocking puzzle. When it was published in Progressive Architecture in 1992, the editors labelled it a "triangular stencil."

The Parkwood Apartments (1948, demolished) were designed by Raymond Brogniez, then on the staff of the William G. Farrington, Co. In this garden apartment complex were 75 four-unit loadbearing masonry buildings on a 30-acre tract adjacent the VA Hospital. The Parkwood Apartments won first prize in the rental category for the National Association of Homebuilders’ 1950 Neighborhood Development competition. Today the vacant shell of the Baylor Hospital (HOK, 2009) is located on the site.

An addition to Hermann Hospital and the 15-story Hermann Professional Building were both designed by Kenneth Franzheim and Wyatt C. Hedrick, and completed in 1949.

The wildcatter Glen McCarthy’s Shamrock Hotel and Community Center were designed by Wyatt C Hedrick (1949, demolished) and originally planned with a shopping center, ice rink, and highrise apartments. The hotel was demolished in 1986 amid great protest. The epic movie Giant, featuring Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, and James Dean, immortalized McCarthy's excess.

In 1991 the Gus S. and Lyndall F. Wortham Park was dedicated on part of the site of Shamrock Hotel. (The rest of thee site is a giant parking lot.) It was designed by Philip Johnson's ex-partner John Burgee and features water jets, columns that appear to be taken from a freeway overpass and vine covered pergolas. It makes a nice, very secluded place to take a nap during the afternoon since it is always deserted.

1950s to Mid-1960s — Golden Age of Postwar Modernism

A masterwork of local 1950s modern architecture was demolished this year. The current owner, The University of Texas, demolished the Prudential Building to accommodate a new office building of similar size elsewhere on the site.

When it was dedicated on July 29, 1952, the Prudential Building was the second modern skyscraper to be built in Houston. Houston architect Kenneth Franzheim and his chief designer, Anton Skislewicz, imbued the building with a sense of urban style and suburban comfort that was never quite equaled in any of Franzheim’s other Houston projects. The ground level walls of the Prudential Building were clad with deep-red polished Texas granite; the upper floors on the northwest and northeast sides were clad in Texas limestone. The southwest and southeast sides, though, were faced with a “unique full-height aluminum arrangement... that will utilize solar rays and air circulation to effect economies in air conditioning.”

In front of the building`s public façade, along Holcombe Boulevard, stood a fountain without equal in Houston. The fountain consisted of a simple rectangular pool with a row of bronze nautilus shells shooting jets of water at a limestone sculpture entitled Wave of Life by noted American artist Wheeler Williams, which depicts a recumbent man and woman holding aloft a child symbolizing the future. Visitors were welcomed with a wide flagstone terrace surrounded by azaleas. At the rear of the building there was an Olympic swimming pool surrounded by an elaborately patterned terrazzo deck shaded by a free-form steel and corrugated fiberglass sunscreen.

Franzheim articulated these exterior spaces with different types of paving and level changes to make the precincts around the water feel cool and secluded. This feeling was augmented by landscape architect C. C. Pat Fleming's lush subtropical planting scheme for the 27-acre site. The pool and Fleming`s gardens are gone. The terrazzo paving from the entrance continued into the lobby, which was fitted with curved walls paneled with tropical hardwood veneers and richly veined Chiaro marble revetments. Directly opposite the front doors was a mural painted in tempura on plaster by famed artist Peter Hurd entitled The Future Belongs To Those Who Prepare For It. It depicts a group of Texas farmers gathered about an oak tree with the produce of the land arrayed around them in American Scene style.

M.D. Anderson Hospital and Tumor Institute now. 1515 Holcombe Boulevard.

UT Dental Hospital, MacKie & Kamrath, then. 6516 John Freeman Avenue.

UT Dental Hospital now

Medical Towers Building now.

Mayfair Apartments, Lloyd & Morgan. 1600 Holcombe Boulevard.

Tidelands Motel, Winfred O. Gustafson. Main Street & University Boulevard.

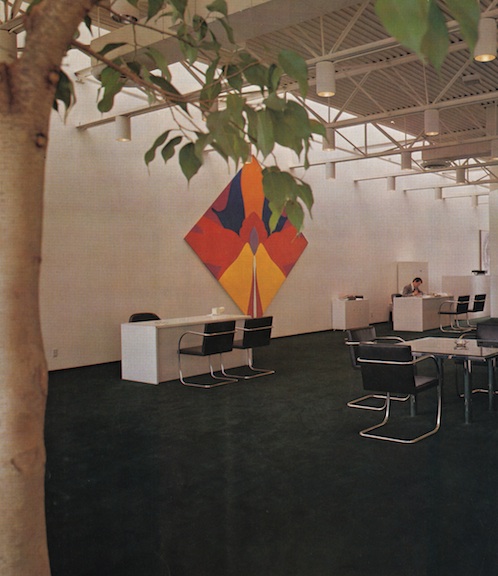

Medical Center National Bank, John A. Greeson and Brown & McKim, 6631 Main Street.

Medical Center National Bank interior.

Kelsey-Leary-Seybold Clinic Building, Wilson, Morris, Crain & Anderson. 6624 Fannin Street.

Texas Institute for Rehabilitation and Research Building, Wilson, Morris, Crain & Anderson. 1333 Moursund Avenue.

Houston State Psychiatric Institute, George Pierce-Abel B. Pierce.

Houston State Psychiatric Institute. 1300 Moursund Avenue.

First Professional, S. I. Morris Associates. 6436 Fannin Street.

First Professional interior by Sally Walsh.

One exception in the 1970s was the diminutive First City Bancorporation Building (1974, demolished) designed by S. I. Morris Associates (Alsey Newton was the partner in charge and Sally Walsh designed the interiors). Also known as First Professional, it was located on the commercial strip between Fannin Street and Main Street that was seeing a lot of construction activity. To take advantage of rising land prices, the owners of the building insisted that it be designed to be easily dismantled after a few years. Newton’s crisp, late modern design was for a two-story prismatic building with cheap concrete tilt-up walls, exposed bar joists and flush windows of solar gray glass. Walsh’s spare interiors provided a splash of color and complemented the simple architectural shell. The building won a design award from both the Texas Society of Architects and the Houston Chapter of the American Institute of Architects in 1975.

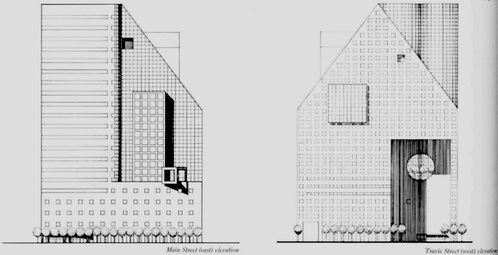

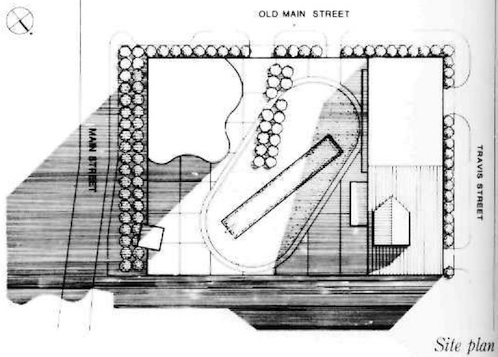

International Medical Complex Building, Arquitectonica. Travis Street & Main Street.

International Medical Complex Building plan.

St. Luke's Medical Tower; rendering, Cesar Pelli & Associates. 6624 Fannin Street.

St. Luke's model showing unbuilt towers.

Tallest buildings left to right: Memorial Hermann Medical Plaza, Methodist Hospital Outpatient Care Center, and St. Luke’s Medical Towers. 6400 Fannin Street.

Methodist Hospital Outpatient Care Center (on left, tallest), Smith Tower (on right, second tallest). 6445 Main Street.

John P. McGovern Texas Medical Center Commons, Jackson & Ryan Architects.

Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute, Perkins & Will. 1250 Moursund Street.

Methodist Hospital Research Institute, Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates and WHR Architects.

Lowry and Peggy Mays Clinic, KMD Architects. 1200 Holcombe Boulevard.

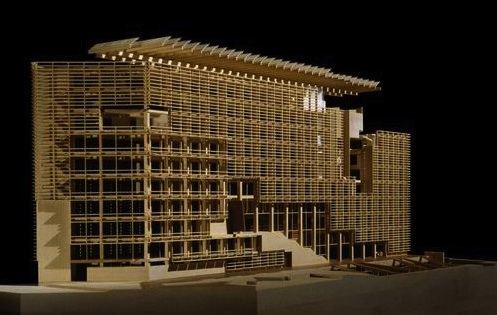

Proposal for nursing building by Patkau Architects

Proposal by Patkau Architects

Fayez S. Sarofim Research Building, BNIM and Burt Hill Kosar Rittelmann Associates. 1825 Pressler Street.

Texas Children's Hospital Women's Pavilion, FKP Architects. 6651 Main Street.

Texas Children’s Hospital (1953, extensively altered), designed by Milton Foy Martin, was three-stories tall with a four-story section above the main entry. The long north-south elevations were distinguished by the consistent use of overhanging, flared aluminum fins that served as solar shades for the patient rooms. The short-end elevations were solid brick. In 1955, the building won a design award from the Houston Chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), as well as a national design award from the AIA.

MacKie & Kamrath, Houston’s best-known proponents of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian architecture, designed the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Hospital and Tumor Institute (1954, extensively altered) and the University of Texas Dental Branch Building (1954, currently scheduled to be demolished). Both were distinguished by their use of Georgia Etowah pink marble. The celebrated furniture designer Florence Knoll designed the interiors of the M.D. Anderson Hospital. Only one wall of the original hospital remains visible. In 1954, Time magazine dubbed the hospital the “Pink Palace of Healing” in a feature article on its architectural innovations, and in 1955 the building won a medal of honor from the Houston AIA.

As the Dental Branch Building appears more or less in its original state, it allows one to still see the wonderful detailing that MacKie & Kamrath devised for it. In 1951, the editors of Progressive Architecture declared it one of the most innovative new medical buildings in the nation, in an annual survey that a few years later would become formalized as the P/A Awards program. M.D. Anderson Cancer Center recently informed Texas Historical Commission of its plans to demolish the building.

Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM) is the New York-based architectural firm that single-handedly defined classy corporate architecture in the United States for the first two decades after World War II. They designed their first building in Houston, the Medical Towers Building (1956), as design consultants to the Houston firm Golemon & Rolfe. The building takes the tower and podium parti of SOM’s recently completed Lever House (1952), but where Lever House has office space in the podium, the Medical Towers has parking space, and where the ground level of the Lever House is open and raised on columns to allow for public access, the Medical Towers has shops. In a concession to Houston’s hot, sunny climate, the long elevations of the rectangular tower are clad with a curtain wall of turquoise, enameled-steel panels that alternate with narrow strips of dark gray, tinted solar glass. The narrow end walls, roughly facing east and west, are solid brick. In 1954, the building won a design award in the first annual P/A Awards program. The Medical Towers Building went on to win a national design award from the AIA and a statewide design award from the Texas Society of Architects, both in 1957. It also won a design award from the Houston AIA in 1960.

Lloyd & Morgan designed the 14-story Mayfair Apartments (1957, demolished) on Holcombe Boulevard. Like several of the other buildings from the same time, their elevations were articulated by the placement of glass on the long north and south sides with sunshades and narrow, solid walls facing east and west.

The Tidelands Motel, designed by the Austin architect Winfred O. Gustafson (1958, demolished) at the corner of Main Street and University Boulevard was one of Houston’s swankiest of the postwar years. It was later used by Rice University for graduate housing. The site is now home to the Bioscience Research Collaborative building.

The curving front elevation of the pavilion-like Medical Center National Bank building (1960, demolished) used panels of marble inset into a metal frame to provide filtered light into the banking hall.

Significant buildings from the late 1950s and early 1960s included the Texas Institute for Rehabilitation and Research Building (1959, altered) and the Kelsey-Leary-Seybold Clinic Building (1963, demolished), both designed by Wilson, Morris, Crain & Anderson. George Pierce-Abel B. Pierce designed the Houston State Psychiatric Institute For Research and Training Building (1962, demolished). These building represented a new trend in modern architecture, Formalism, where symmetry and ornament began be used in modern design. The Texas Institute for Rehabilitation and Research Building and the Houston State Psychiatric Institute For Research and Training Building both made extensive use of pierced concrete blocks to create patterned screen walls and the Kelsey-Leary-Seybold Clinic Building had its exposed structurally column and beam system clad with decorative marble paneling. The Houston State Psychiatric Institute For Research and Training Building won a design award from the Houston Chapter of the American Institute of Architects in 1962. The Kelsey-Seybold Clinic building won a national design award in 1967 in a competition administered by American Institute of Architects and Marble Institute of America.

Mid-1960s to 1980s — Halting and Vaulting

From the mid-1960s through the 1980s, many new buildings appeared in the Texas Medical Center, but only a handful come close to the architectural distinction of the second-generation buildings.

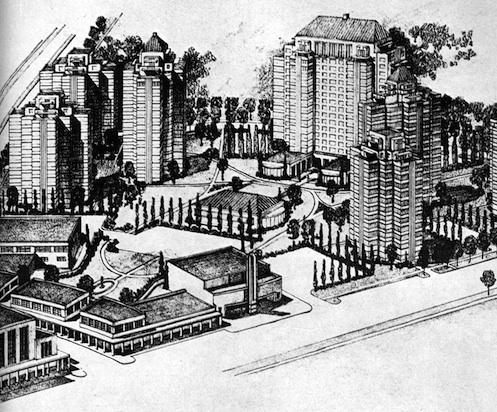

The 1980s also saw a few interesting projects. The most intriguing was Arquitectonica’s brash, postmodern design for the International Medical Complex Building (1982, not built). It was to have been built at Main Street and Old Main Street one block north of Holcombe Boulevard. The International Medical Complex was to have a six-story base containing a shopping mall on the ground level with a parking garage above it. On top of the garage were to be two, sculptural freestanding towers, one containing a hotel and the other medical offices. It was proposed in 1982 and, needless to say, the real estate crash in Houston that followed almost immediately killed plans for its construction.

1990s-2000s — Imaging

Perhaps as a reaction to mostly bland and boring buildings of the 1970s and 1980s. The buildings in the Texas Medical center from the 1990s and 2000s seem to exhibit a tendency for greater imageability. Although this is not in itself a negative thing (think Empire State Building, for example) in the hands of the wrong client and architect it can verge on disastrous. Far and away the best of these was also the first, the St. Luke’s Medical Tower.

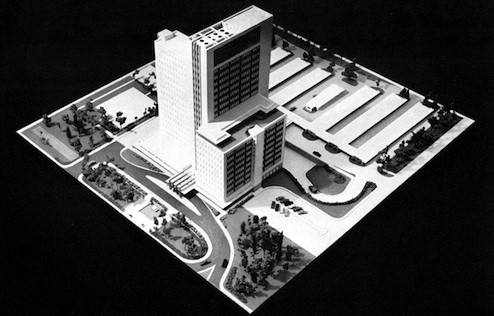

The 25-story St. Luke’s Medical Tower (1991) was designed by Cesar Pelli & Associates and Kendall/ Heaton Associates. In what was becoming a recognizable trend, this building was located in the commercial strip adjacent to the Texas Medical Center between Main and Fannin Streets. Pelli, master of the slick curtain wall, used it to great effect here. The office tower, which rises above a nine-story parking garage, is shaped into twin octagonal towers surmounted by tall, spiky needles. Resembling twin syringes ready to shoot their serum into the heavens, the silvery, mirror-glass-clad St. Luke’s Medical Tower provides a much-needed landmark for the center’s otherwise drab skyline. An early model of the project showed several sets of of the needle-like towers.

The Texas Medical Center’s other two skyline landmarks, the Memorial Hermann Medical Plaza (2007) designed by Kirksey and the Methodist Hospital Outpatient Care Center (2010) designed by WHR Architects demonstrate the how the model of the St. Luke’s Medical Tower were ignored by later architects.

The Memorial Hermann Medical Plaza substitutes a monolithic slab that hovers ominously over the Rice University Campus for St. Luke’s elegantly tapered, octagonal towers. (See Julie Eakin’s article about it in Cite 72 for a mostly positive review of the building.) Possibly to compensate for its shapelessness, the architects devised a large cap that takes the shape of an inverted mastaba that is lit up with brightly colored LED lights on some nights.

At one time, Methodist commissioned understated building, like the Smith Tower (1989) designed by Lloyd Jones Fillpot & Associates, with its garage in the foreground clad with sleek, aluminum fins. The Methodist Hospital Outpatient Care Center (2010), on the other hand, is the tallest building in the Texas Medical Center at 512 feet to the top of its spire. It is nearly half parking garage (776,000 square feet to 824,000 square feet of office space). The upper section of this building is a fat triangle with bulging sides. It is capped by a decorative superstructure that gives it a vaguely ship-like look. While the imagery of St. Lukes (hypodermic needles) is almost too appropriate for the Texas Medical Center, the nautical motif at Methodist seems to come out of nowhere and does not relate in a meaningful way to its location. At night, it too is lit up with lights, but they are all blue instead of changing colors.

Another example that exemplifies the general level of design of the newer buildings is the John P. McGovern Texas Medical Center Commons (2002) designed by Jackson & Ryan Architects. Although ostensibly a public building, its program is dominated by hourly parking. The ground floor, which contains a food court is sandwiched above and below by a parking garage. On top of the parking garage is a more formal restaurant, Trevisio. To conceal the many levels of parking there are two fifty-five foot tall waterfalls which flank a gently curving central panel featuring the building’s name carved in large letters. The waterfalls, like a miniature version of Niagara Falls, actually repel pedestrians due to the spray they cause at the base of the garage. However on hot days this can be pleasant and the minerals that have been deposited on the surfaces of the building by the constant mist give it the air of a geological feature of some antiquity.

A final example is the Texas Children’s Hospital’s Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute (2010) designed by Perkins & Will. As with the Methodist Hospital Outpatient Care Center, it relies on a goofy shape for cachet. Here there is a series of rotated glass boxes appended to its outermost corner.

2010s — City of Medicine

From about 2010 onwards, new buildings have moved the Texas Medical Center towards somewhat more urban goals.

Methodist Hospital Research Institute (2010), designed by the New York firm Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates and the Houston firm WHR Architects, may look corporate, but it has the virtue of at least being very tasteful. What's more, the yin-yang relationship it establishes with the convex, curving facade of the neighboring St. Luke's Episcopal Hospital Denton A. Cooley Building for The Texas Heart Institute (2002), designed by Morris Architects, is really quite compelling.

In direct contrast to the new Methodist building, the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center's Lowry and Peggy Mays Clinic (2005), designed by KMD Architects, is a delirious pile of turquoise-tinted mirror glass and pink precast concrete, complete with a neo-Babylonian hanging garden of healing.

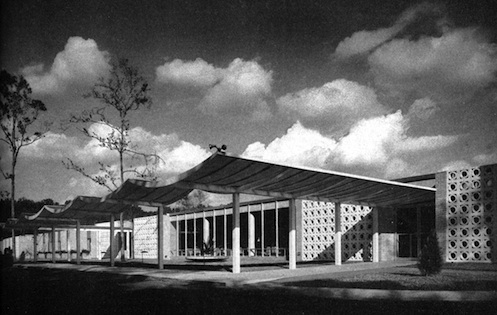

In 1996, the administrators of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston hosted an invited architectural competition to design a new building for the University of Texas School of Nursing. The ambitious competition’s roster of prominent architects who participated included Rodolfo Machado/Jorge Silvetti, Taller de Enrique Norton y Asociados, Lake|Flato Architects, Tod Williams Billie Tsien & Associates, Steven Holl Architects, and the winner, Patkau Architects of Vancouver. The husband and wife team of Patkau, which has a reputation for green architecture, proposed an elegantly louvered, elongated slab for the building. Due to mixed messages from the client (asking the designers to lower the cost to $40 million, but keep the features that required a $60 million budget), Patkau eventually resigned from the project in 2000 after having worked on the design for four years. BNIM, a Kansas City-based firm noted for sustainability, and Lake|Flato were subsequently hired. Completed in 2002, the building is marked by a startling combination of materials and forms. The final cost was $58 million. Though this author prefers the Patkau proposal, it should be noted the building won a design award, as well as an award for its sustainability, from the Houston AIA in 2005, and a design award from the Texas Society of Architects in 2006.

The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston's Fayez S. Sarofim Research Building, designed by BNIM and Pennsylvania-based Burt Hill Kosar Rittelmann Associates, was completed in 2006. The building's engagement with Brays Bayou heralds the linear green spaces envisioned by the latest medical center master plan.

A new addition to the medical center, completed in 2012, the Texas Children's Hospital Women's Pavilion, designed by FKP Architects, is distinguished by an enormous, two-story pedestrian bridge separating hospital workers from civilians. Large bridges such as this may be the new norm, as the latest medical center master plan calls for buildings to reserve space on the second and third floors for pedestrian and utility connections.

Hope for a Balanced Vision of Growth and Community

The newest buildings---The Methodist Hospital Research Institute, Fayez S. Sarofim Research Building, and University of Texas School of Nursing, in particular---are tentative steps in the right direction towards "good taste" or at least a move away from the increasingly outlandish designs. These buildings also indicate an awareness of sustainability and represent site specific architectural responses that take into consideration the unique context of the Texas Medical Center.