This essay appears in a slightly different form in the new issue of Cite, "The Beautiful Periphery." The issue is available for purchase at Brazos Bookstore and River Oaks Bookstore, as well as the bookstores at the Menil Collection; The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Contemporary Arts Museum; and the Blaffer Art Museum. Read more from Cite 94.

There is a stubborn and widening gap like the one between the rich and the poor, in how we imagine our cities and the reality on the ground. The time-honored suburban stereotypes of homogeneity, conformity, and middle-class banality are as unmoving and obstinate as a giant rock, regardless of the actualities. It is as if we are blind, or perhaps just don’t want to see. But big changes have occurred in this landscape of strip centers, shopping malls, subdivisions, and apartment complexes — change big enough to completely eradicate labels, yet somehow they hold. Some designers are paying attention, but their vision is too often to retrofit the suburban landscape into a semblance of the nineteenth-century city — a feat that is far too nostalgic and flawed. So while designers look to the past for inspiration, ground-up action transforms the present in hopes of a brighter future. What I define as the “New Projects,” distressed and disinvested multifamily housing, is one story of transformation, among so many that could be told.

To begin, while the old public housing “projects” have been demolished in Chicago to make way for saccharine-sweet mixed-income neighborhoods — in cities like Houston (and suburbs throughout the U.S.) disinvestment, changing desires, and shifting socio-economic and spatial conditions are combining to create the “new projects” on the periphery. The new projects look nothing like the old, mixed from one part JG Ballard’s Super Cannes and one part Herbert Gans’ Urban Villagers; the large multi-family developments follow a suburban superblock model — privatized, gated, and disconnected from the surrounding city. The new projects were built quickly and cheaply in the 1970s and 1980s, most often for young professionals, and with little open space or amenities. Today, these projects are increasingly home to more families than singles and a vastly expanding number of people who live below the poverty line. Furthermore, in the absence of a national housing policy, where vouchers constitute the largest portion of low-income housing subsidies, this housing is, in many ways, the new de facto public housing and subject to many of the same challenges public housing communities faced 50 years ago.

In Houston the scale of the problem, and the potential salvaging effect of a solution, is immense. 315,357 is the number of multifamily apartments housed in buildings comprised of 10 or more units. Forty percent of this housing, or just over 140,000 units, were constructed between 1960 and 1979. Today, this housing is home to more than 20 percent of Houston’s two million residents. The units are dispersed in roughly 600 separate complexes, with an average of 250 units, and typically constructed at densities of 30-40 units per acre. Not surprisingly, the new projects are located predominantly outside the Loop and many are in a downward spiral of disinvestment. At the scale of the neighborhood, the new projects are islands, privatized and disconnected from the surrounding context and resources. At the scale of the complex, parking is the most prominent landscape feature and the open space that does exist is often undefined, lacking boundaries to contain it or shape it, and therefore belonging to no one. In most complexes, social organization, open space, public infrastructure, and a sense of control and ownership are all missing.

Disinvestment and displacement have created the new projects, distant from the prosperity and opportunity of the center, and these projects have become affordable at the very moment that they have become less desirable. Two examples, St. Cloud and Thai Xuan Village, illustrate how grounded and organic change can transform decline into opportunity. The third case, Greenspoint, serves as an example on the opposite side of the spectrum.

St. Cloud, Gulfton

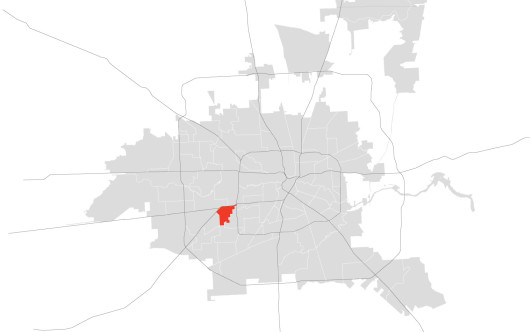

It was a warm and muggy day in July when I first toured the St. Cloud apartment complex on Hillcroft. What I found was a quiet oasis in the center of one of Houston’s densest, poorest, and most diverse neighborhoods — Gulfton. St. Cloud is a simple garden apartment complex — one of nearly 50 similar complexes in a three-square mile area that combined total 15,000 units. Once a prime destination for young professional singles moving to the city in the 1970s, Gulfton began transforming in the late 1980s when Houston’s economy collapsed with the price of oil. As single professionals moved on to greener pastures, new immigrants began arriving in the city and filling vacated units. Today more than 60 percent of Gulfton residents were born outside the U.S. and poverty sits at a staggering 39 percent.

But St. Cloud stands in stark defiance of expectations. Home to primarily ethnic Nepalese refugees from Bhutan, it is indescribably beautiful — it works like an “urban village” of the kind that Herbert Gans defined in his 1950s study of the West End of Boston. In the West End Gans found that regardless of the plentiful studies defining the area as a “slum” (clearing any resistance to complete erasure) that the social networks and support systems in place created a neighborhood that worked, and worked well. Gans writes in The Urban Villagers that the “image of the area gives rise to feelings that something should be done, and subsequently the area is proposed for renewal. Consequently, the planning reports that are written to justify renewal dwell as much on social as on physical criteria, and are filled with data intended to show the prevalence of antisocial or pathological behavior.” Facsimiles of this quote can be heard today, not in reference to historic city districts, but instead to the big multifamily complexes in struggling neighborhoods.

Sited on a superblock over 600 feet in length, St. Cloud is an island, gated and set apart from the surrounding neighborhood. The repeating pattern of courtyards and parking areas are framed by two-story buildings that open to the front and back. This pattern creates the condition where all the units face the open courtyards. As a result the well-defined courtyards are the central gathering and play areas. At one time there were four pools in these spaces; today all have been filled in. On the site of one former pool is an ad hoc and petite soccer field, with a 10-foot fence to prevent the adjacent apartment windows from being broken. On any day you can find men gathered in the courtyard playing the traditional board game carrom, children playing freely, mothers chatting on chairs moved outside to supervise, and pickling jars and container gardens dotting adjacent balconies and carports. In many ways the spatial definition of the courtyards has created a shared and safe space, that is both central and watched over by all the residents.

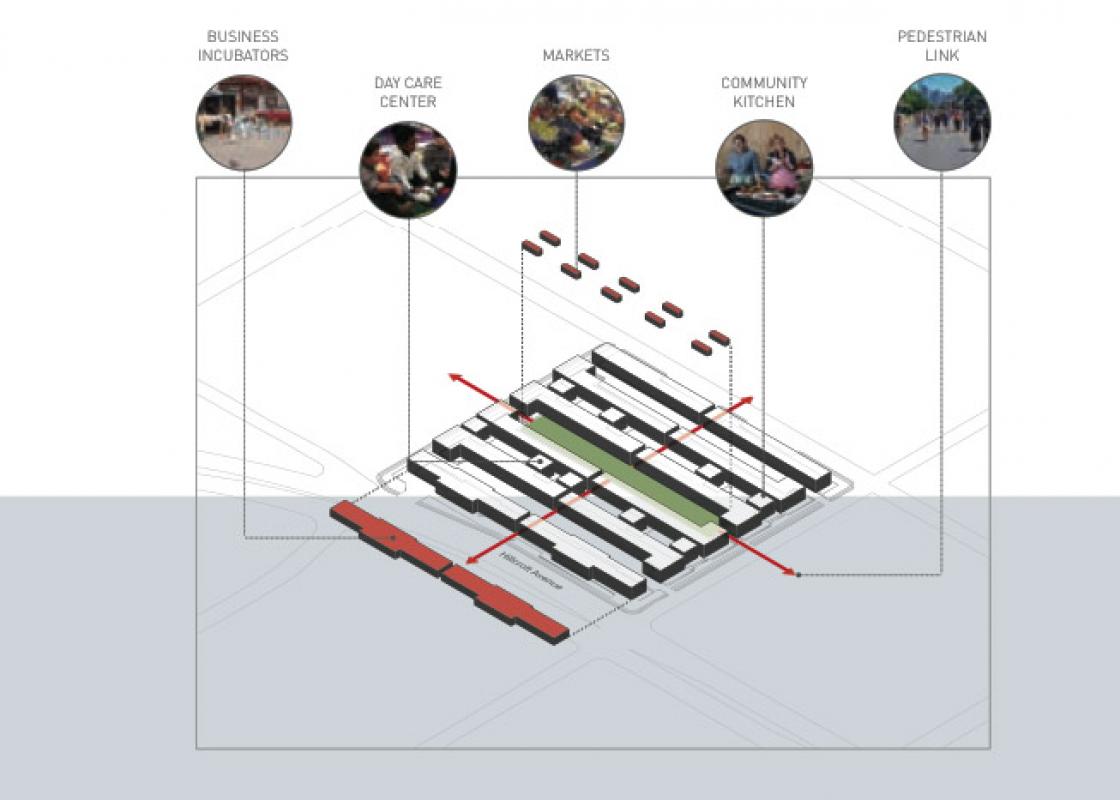

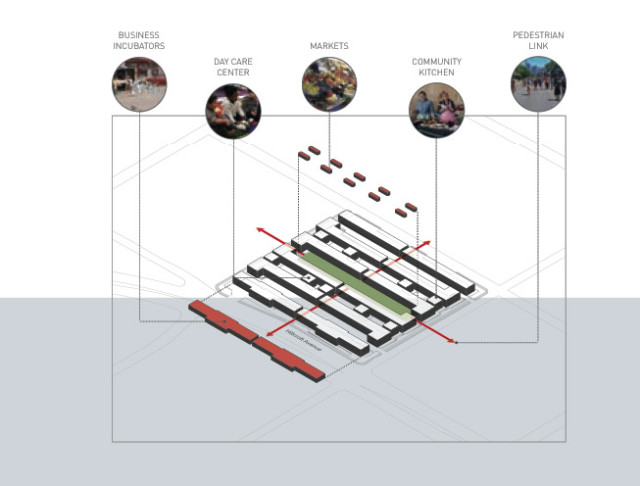

A former apartment now serves community needs and there is talk of transforming the laundry areas into community kitchens or other social spaces. What is happening at St. Cloud is a micro-model of transformation that could be expanded by adopting the more ambitious strategies suggested by Jane Jacobs in Death and Life of Great American Cities. Jacobs recommended that the ground floor of project buildings be gutted and replaced with a mix of uses or more temporary vendors and markets, and that new streets be introduced to weave projects into the surrounding context. Imagining this model at St. Cloud, for example, would translate into creating new streets through the existing parking lots and introducing new entrepreneurial uses in buildings adjacent to major streets.

Thai Xuan Village

The story of Thai Xuan Village has been told, but its lessons remain buried. The complex, built in 1976, was originally the Cavalier Apartments. It is one of 20 complexes that line the one-mile corridor of Broadway near Hobby Airport, flanking the repositioned Glenbrook Valley subdivision. The southeast side of Houston was once “swank,” and young professionals and families flocked to the area in the 1950s and ’60s. As it seems all good things must come to an end, the flight to more distant suburbs (particularly western ones) and the economic crisis of the 1980s ushered in a period of decline. When flight attendants fled and other young professionals moved on; disinvestment followed. In 1993, a Vietnamese Catholic priest, Father John Chinh Tran, bought the complex, renamed it Thai Xuan Village, and invited new refugees from South Vietnam to live there. In 1996, the complex was sold unit by unit as condominiums, and are today appraised at values between $5,000 and $10,000. This would be the start of a new, but rocky, future.

Over the next 15 years the complex deteriorated, balconies sagged, railings collapsed, and broken windows hinted at an escalating crisis. In 2007, elected officials, responding to pressure from neighboring community leaders, began threatening the owners with demolition. The residents fought back, organized a tenant organization, and in 2009 secured $250,000 in affordable housing funds to upgrade the complex. The sagging balconies are once again plumb, roofs have been repaired, and the exterior has been painted and cleaned.

Today, Thai Xuan Village remains imperfect, but worth understanding. In the center of the complex is a small outdoor chapel, placed prominently in the courtyard that once housed a pool, now filled in. Tenants grow vegetables and fruits in their small fenced yards or on the balconies, a small store occupying a former apartment serves residents’ basic needs, and children play basketball on the slab of a demolished building. As Josh Harkinson writes in the Houston Press:

Any sidewalk between any two buildings leads into a valley of microfarms crammed with herbs and vegetables that would confound most American botanists. Entire front yards are given over to choy greens. Mature papaya trees dangle green fruit overhead, and vines sagging with wrinkled or spiky melons climb trellises up second-story balconies. Perfumed night jasmine stretches for light alongside trees heavy with satsumas, limes, and calamondins. Where the soil ends, Vietnamese mints and peppers sprout out of anything that will contain roots . . .

The changes at Thai Xuan Village are entirely organic. The gradient from public to private space, a favorite mantra of designers and housing specialists alike, has been well defined, moving from the shared public courtyards to the semi-public fenced gardens and patios to the individual units. As a result the maze-like quality of the open spaces has become more defined and more useful. Continuing to support the infusion of adaptive entrepreneurial uses, like the existing small store, could create additional economic opportunity and more lasting change, not just in the complex, but in the surrounding neighborhood.

St. Cloud and Thai Xuan Village illustrate the potentials of ground-up change in Houston’s large multifamily complexes, but more needs to be done to ensure that affordable housing in dense and well-served neighborhoods is preserved. Which takes us to Greenspoint.

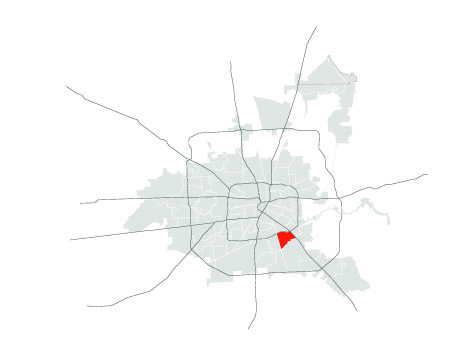

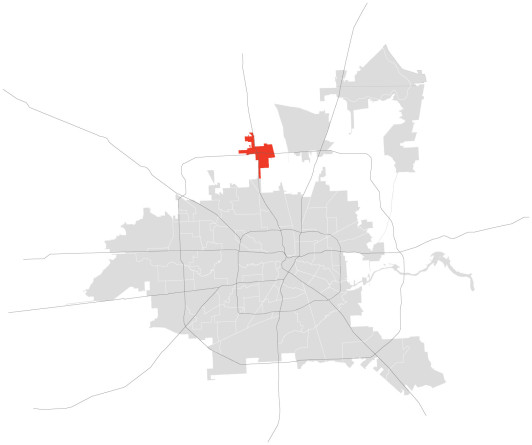

Greenspoint

The profound demographic shifts that have occurred in the last 20 years come sharply into focus in the Greenspoint neighborhood. The seven-square-mile neighborhood, appallingly nicknamed “Gunspoint,” has one of the highest concentrations of multifamily housing within the city limits, at 11,000 units. Over the last 20 years, working-class families have replaced single-person professional households, and as a result, population density in the neighborhood has increased by a factor of 1.5. For example, according to the U.S. Census, only 2,500 people below the age of 18 lived in Greenspoint in 1990. By 2000, this number had skyrocketed to over 12,400, and by 2010, it climbed yet again to 14,000 representing 36 percent of the total population. Over 34 percent of households currently live below the federal poverty level. Compounding a challenging situation, there are few basic amenities such as grocers, pharmacies, community services, libraries, or youth programs available to Greenspoint residents. Over 24 percent of households do not own a car and depend solely on relatively limited public transportation.

Greenspoint is a community divided — islands comprising a large and dying mall, office towers, multi-family housing, and strip retail development are disconnected and isolated from each other both physically and demographically. An immense scale compounds the division. For example, on the site of Greenspoint Mall you could put 54 downtown Houston blocks. Fundamentally there are two communities —one that caters to area office workers and one for those who call the neighborhood home. The division is exemplified by the fact that stores and restaurants serving the area’s office workers are closed in the evening and on weekends. Greenspoint will soon be dealt another hefty blow when Exxon moves 5,000 employees from the neighborhood to their new campus in Spring.

While I can’t claim to be an expert, Greenspoint, like South Park and other Houston neighborhoods, has produced a lucrative hip-hop and underground rap scene. For those of us old enough to remember rap’s early days, it is perplexing to see a mall (where you can get all your Greenspoint wear), apartment complexes, and suburban-style single-family homes featured in street-style, badass rap videos. On the other hand, it makes it clear that local hip-hop culture is one place where demographic change is not studied, it is lived.

What does the future hold for Greenspoint? I would like to say a music production incubator, a space for Kaos TV, a program like Workshop Houston in Third Ward, or simple programs for youth and families — all this and much more could just occupy the vacant spaces in the mall — but it seems this is not quite the trajectory. One real estate investment company now owns 11 complexes totaling 2,712 apartments, or 25 percent of all of the multifamily units in the neighborhood. Steve Moore, one of the owners, has established a reputation as the “fixer” for distressed apartment complexes in Houston and has moved into the neighborhood. In his recent interview on

KTRK, he notes that he is getting rid of drug dealers and criminals, investing in lighting and security, and has established a new set of ground rules for residents, which include a 10 p.m. curfew and no “baggy” or “skimpy” clothing. Greenspoint Mall also has a no-“baggy”-pants policy. Whether these changes are intended to create greater opportunity for the families that live in Greenspoint today or entice the young professional crowd back to the area is, as of yet, unclear. But the organic change happening at St. Cloud and Thai Xuan Village is yet to emerge.

Conclusion

The mayor keeps a list, dubbed the “dirty half dozen,” which identifies blighted and distressed properties ripe for demolition. Troubled apartments are one of the biggest targets. The last published list of six, now demolished, included five apartment or condominium complexes and one motel. Over a three-year period ending in January 2013, the city demolished a total of 1,120 multifamily units. The question is what will we do with the remaining 310,000 units or so of which 150,000 are more than 40 years old? Demolition would create a twenty-first century re-development opportunity at a scale not witnessed since the era of urban renewal and would remove hundreds of thousands of affordable units from the market. Instead, we could learn from the innovative models that are emerging organically as complexes and apartments are retrofitted for charter schools, places of worship, community centers, small businesses, and youth programs, and formerly ornamental green spaces are transformed into vegetable gardens, sports fields, and gathering places. Meanwhile, the suburban model of large-scale gated and privatized developments is being transplanted into the core of our cities, and the lessons that should seem evident in their failures remain buried.