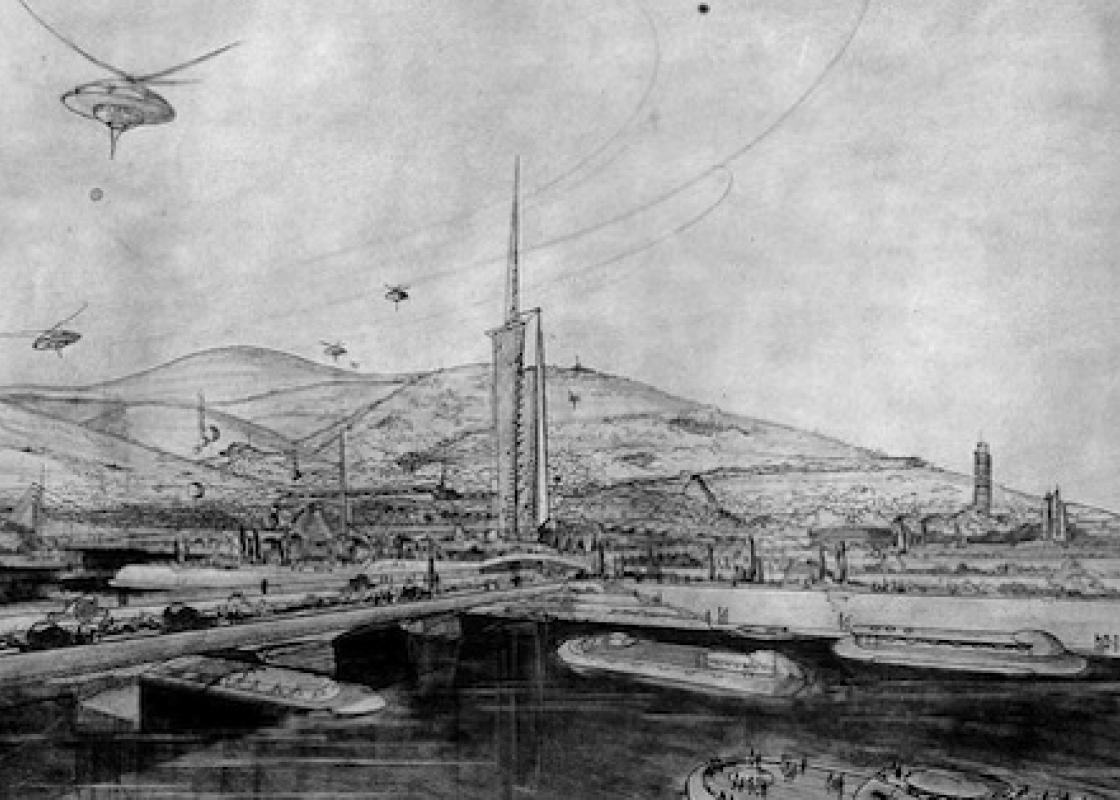

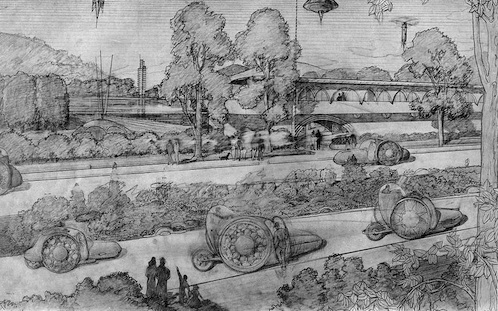

Frank Lloyd Wright sketch for Broadacre City

The eight-week course “Spotlight on Rice University School of Architecture,” which is offered by the Glasscock School of Continuing Studies, began on Tuesday with an introduction by Dean Sarah Whiting to architecture as an academic discipline. The focus on how architecture is taught and studied required an examination, in turn, of how architecture is represented in photography, painting and drawing, and modeling, as well as the typical plans and sections we associate with the architectural blueprint. By means of a robust slide show of such images, Dr. Whiting made the case for the tendency of architecture as a subject of study toward advancement and innovation.

Indeed the first half of the slide show featured images from the 20th century’s greatest architectural speculations, a great-hits rally of what Whiting called “imagined futures” including the Italian Futurists, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), and Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Broadacre City” (1932), le Corbusier’s “Ville Radiuse” (1935), and moving into later examples like Paul Rudolph’s “Lower Manhattan Expressway” (1967).

The most wildly inventive examples ventured to disregard the limitations of existing technology and then ended up anticipating technologies to come. For example, steel-frame construction, which makes the building of skyscrapers not only possible but also ordinary, was not available to the Italian Futurists in 1914, whose designs for tall, sleek towers were truly unprecedented. How soon, then, will we see the 1968 translucent dome of R. Buckminster Fuller, only most recently imagined in The Simpsons Movie? How soon will our own response to climate change take such seeming extremes? We observed the emergence of a rather sturdy tradition of futures such that we today imagine future worlds by “building onto previous futures.”

This tour through the most fanciful examples of radically restructured cities, buildings, and ways of living served helpfully to liberate us from the ordinary limitations we might set upon our understanding of the architect’s work, and to illustrate how the architect is always in the practice of imagining a future as yet unrealized. Whiting argued at one point that an architect has to be uncommonly self-confident, since her whole profession is to imagine something that isn’t there and then convince other people spend their money making it true.

To show an even more practical example of planning and thinking into the future, Whiting showed a slide of a building project plan, a simple grid of tallied benchmarks and simultaneous effort by which a building contractor coordinates the efforts of many contributors.

Above: Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House, 1951. One member of the class asked, "How are you supposed to live in that?" Imagining new ways to live was the central theme of the talk.

Above: Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House, 1951. One member of the class asked, "How are you supposed to live in that?" Imagining new ways to live was the central theme of the talk.We then turned to examples of architectural innovation that have actually been built, but which continue to advance our understanding of architectural possibility into the future. These proceeded in terms of scale through the house, the city, and the monument. These differences of scale allowed Whiting to consider a full range of other issues involved in the architect’s vision: how people live in cities, how they inhabit their own homes, and how they interact with others in private and public, taking into account not only the aesthetic beauty of a given building, but the psychological, sociological, and political implications of the built environment, as shaped by individual preference, tradition, market forces, and public policy just to name a few.

Whiting had begun by describing architecture as a generalist discipline, one that touches upon all others, and that encompasses an endless sequence of ideas and problems. She related she got into architecture because as a student she didn’t know what to field of study specialize in. In architecture, she could do them all, and her engagement in these multiple and overlapping disciplines was demonstrable in this introductory lecture.