There are two kinds of people in this world: People who appreciate the Rothko Chapel, and those who, upon entry, scratch their heads and wonder what’s for lunch. The interior is a test: Are you willing to open yourself to what might happen if you sit and quiet the mind? Many beloved churches exist in the world, but few capture the dull throb of existence and the possibility of redemption like this space.

This weekend, the Rothko Chapel celebrates its 50th anniversary. Opened in 1971, the chapel quickly became a Houston icon. Nestled under oaks between the Menil Collection and the University of St. Thomas—all here thanks to the founding philanthropy of John and Dominique de Menil—the brick-clad building is an understated, brooding thing. It could be mistaken for a mechanical plant, but this geode-like quality heightens the experience of what’s hidden inside.

Histories

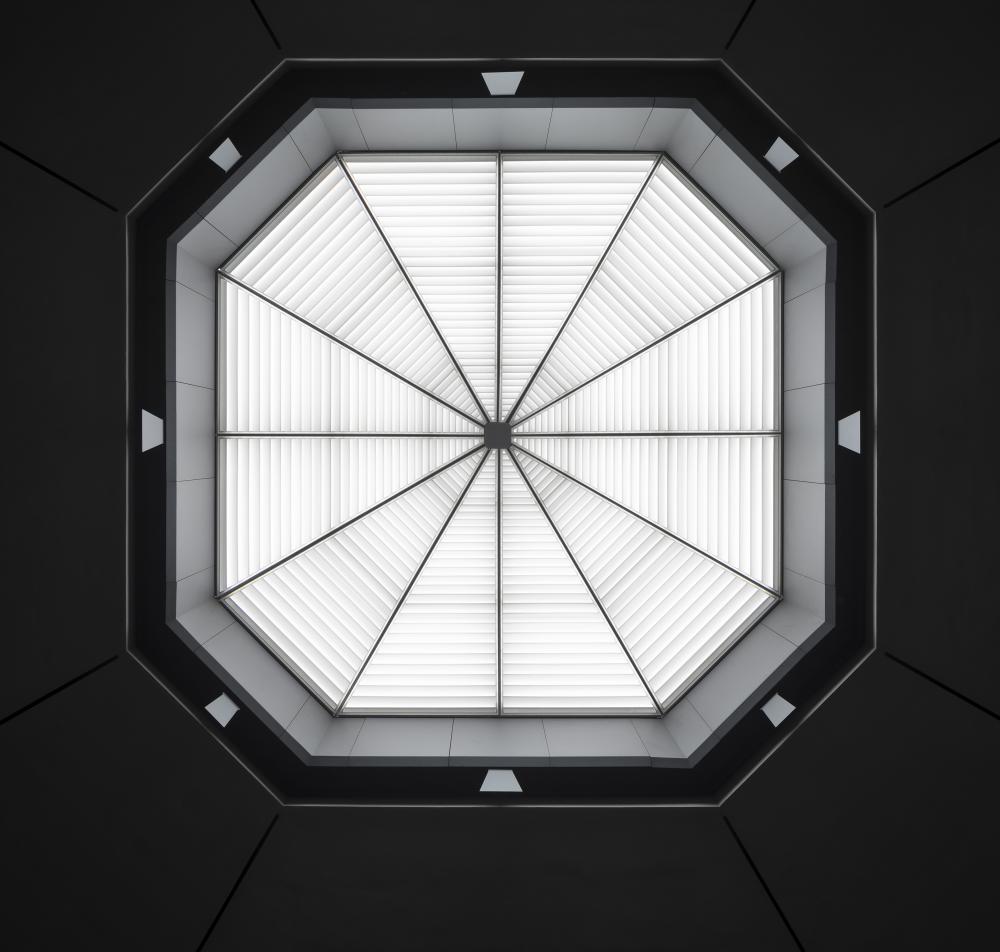

The chapel is cross-shaped in plan, but the interior is an octagon, inspired by Byzantine churches and murals. Mark Rothko never saw this project finished; he committed suicide in 1970 just days after giving the final approval for the chapel’s design. His son Christopher Rothko has been instrumental in leading this restoration and serves on the organization’s Board of Directors.

Fourteen large canvases hang on the chapel’s walls. Their blue-black expanses are portals. They absorb time, light, and attention.

The initial architectural design of the chapel was led by Philip Johnson, but his flashy proposal was soon tossed out, and Rothko then dealt with local architects Howard Barnstone and Eugene Aubry. Barnstone was hospitalized for mental illness in 1968, leaving Aubry to finalize the design. Johnson returned to help with the entrance and the location of the reflecting pool. For more of this history, see Barrie Scardino Bradley’s chapter in last year’s Making Houston Modern: The Life and Architecture of Howard Barnstone.

The simple building was built with a pyramidal skylight that would flood the interior with light. And it did, washing out the artworks and frying observers. Already by 1974, scrim had been stretched across the oculus, and by 1978, a baffle had been installed that cast light across the ceiling, noticeably dimming the interior. A second attempt was made in 1999, darkening the chamber. The gloom settled in, making it hard to discern the intricacies of the canvases. The baffle “sent raking light across the ceiling, so all of a sudden the brightest surface in the room was the ceiling,” said George Sexton of George Sexton Associates, who masterfully handled the lighting design. “One of the things that we were trying to achieve was to make the plane on which the art was hung the brightest surface. And I think we did that.”

Expansions

The renovation of the chapel, led by New York-based Architecture Research Office (ARO), is a serious improvement of the chapel’s sacred space. But it’s also an expansion of the institution’s important work: One goal is the “idea of the chapel as a place for contemplation and self-reflection,” Stephen Cassell, Principal at ARO, said. “And then the other is the chapel as an organization, as a place for social justice and outreach to the local community, the city, and the world.”

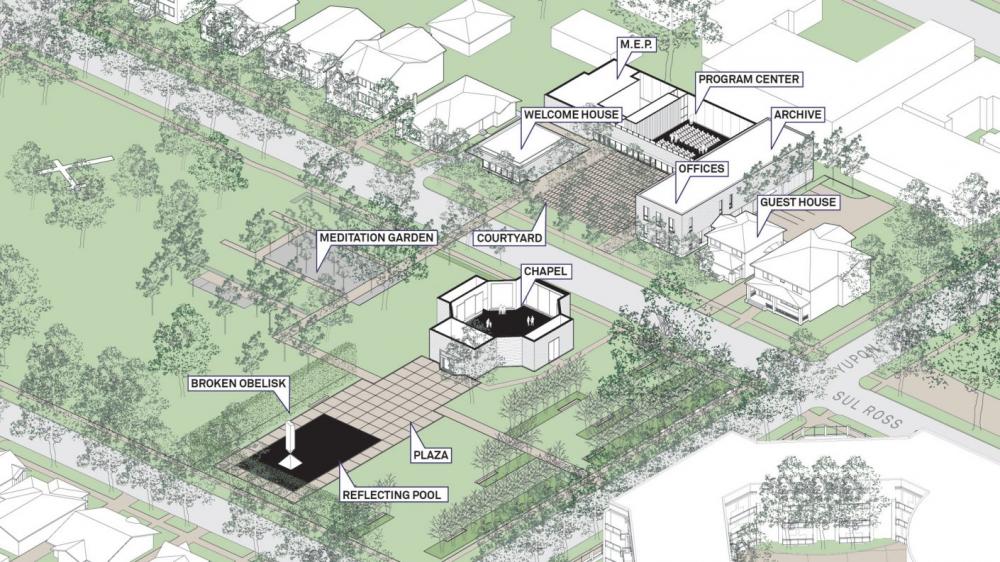

A master plan extends the campus across Sul Ross Street and will ultimately add three new buildings with spaces for guests, programs, offices, mechanical services, and an archive. This effort was carried out with a close reading of the neighborhood’s scale and materials. There’s a “deliberate juxtaposition of the chapel in this residential context,” Adam Yarinsky, Principal at ARO, said. There’s a “directness with which you experience this special place in your everyday life. This is something that we wanted to preserve in the new buildings landscape, and the master plan.”

Among other projects, ARO was prepared for this work after painstakingly restoring 101 Spring Street, Donald Judd’s residence in New York, now maintained by the Judd Foundation. Both Judd and Rothko “expanded the physical boundaries of sculpture and painting by creating carefully calibrated spatial relationships between art and its context,” Yarinsky wrote in a text for The Architect’s Newspaper. In both projects, the challenge was “to reconcile the artists’ original intentions with the ongoing missions of the cultural organizations that perpetuate their legacies.”

The new buildings are designed to blend in with their surroundings. The first phase saw the completion of the Suzanne Deal Booth Welcome House, finished in light brick (matching the chapel), light wood, and gray metal. It functions like a porch: It’s a place for visitors to learn about the organization. An actual M.E.P. building sits at the back of the lot; it will make more sense once the second phase of the master plan is complete.

A forthcoming larger building for gathering is pushed to the back of the lot to preserve the scale of the street and to screen out the adjacent buildings along Alabama Street to the north. Another building with offices and an archive exactly matches the width of the chapel’s apse. Both are clad in wood and are detailed carefully as to not be too loud, Cassell said. An existing home will be moved over and converted to guest housing for visiting lecturers or artists. Immediately west of the chapel, a bungalow will be relocated, and a meditation garden will be built.

The resulting open lawn, enclosed on three sides but open to the street, is informal and offset from the axis established by Broken Obelisk, the chapel, and upcoming office/archive building. This space pairs with a lawn next to the chapel across Sul Ross, and the arrangement establishes a view from the Welcome House across the campus to Broken Obelisk. This scale of the space complements both the rhythm of the street and the chapel itself.

The landscape, designed by Nelson Byrd Woltz, provides an open area next to the fountain and smaller “rooms” created by rows of trees. These alleys are places to gather and sit during Houston’s nice days; they're a welcome spot for lounging during the pandemic. The landscape creates a sense of procession that’s important to the whole experience, Cassell said.

The campus’s lighting design uses the landscape and exterior finishes to prepare one’s eyes for the interior of the chapel, Sexton said. His office also did the lighting design for the Menil Drawing Institute, which uses the procession into that building as a way to adjust one’s pupils for works on paper, which are seen under low light levels. The most dramatic change here is the lighting of Broken Obelisk. Instead of being uplit, it's now illuminated using theatrical projectors discreetly mounted on poles. At night it appears to hover in space, glowing like a molten steel prism.

Improvements

The renovation both hews close to the original design of the Rothko Chapel and makes significant improvements. During this restoration process, the chapel’s exterior brick has been cleaned and repointed, and new paving was installed. Resiliency was also important: A flood gate can now be dropped in before a big storm, the new buildings are built two feet above the curb, HVAC was relocated to the mechanical building across the street, and an emergency generator was included.

In the vestibule, the desk, pamphlets, and other distractions that had accumulated are gone, leaving just a darkened entry chamber that disassociates the viewer from the world. The gray walls are slightly darker than the main space, which reinforces this compression. In the worship space, the walls are still gray, but looking up, the ceiling is flat—a big change from the previous pebbly popcorn acoustical finish.

The new skylight, designed by George Sexton Associates, uses louvers and laminated glass to illuminate the artworks. Sexton calls this device a “collimator,” and it works through subtracting light to create even illumination where it’s wanted. Sexton used large physical models to get the design right and checked his work with computer simulations. The interior octagonal walls of the skylight drum have been refinished, and a deep reveal provides a place for technology, including concealed projectors that require their own ducted systems for cooling and are isolated to reduce noise. Their beams reflect on the floating trapezoidal planes, illuminating the paintings on overcast days.

The effect of this infrastructural work is striking. I had only encountered the chapel in its prior state and was awed, but now the room has even more power. It’s like the axis mundi, Yarinsky said: “The Pantheon in Rome didn't have a baffle under the oculus.” It’s much brighter inside, which allows the canvases to come alive. Once your eyes adjust, they can see a broader range of the colors and textures within the art’s surfaces, qualities that were missed by casual viewers under lower lighting. The same wooden seating and dark floor anchors the room, which is now slightly smaller: The wall of the main niche was moved six inches inward to avoid a shadow hitting the top of the canvases.

Throughout, the construction by Linbeck is precise and clean. They did an amazing job “because they took the time to understand what the goal was,” Cassell said. They “realized the need for mock-ups and sometimes the need to redo something. They were deeply embedded in the process.” If you watched RDA’s recent Who Builds Our City? program, you saw glimpses of this process thanks to Paul Hester’s documentation during construction.

The exacting tonal calibration of Rothko’s paintings—which were said to create a “sense of atmospheric pressure,” according to artist and critic Elaine de Kooning—is here matched by ARO’s skillful architectural leadership. “Sometimes our work is invisible; often there are prominent new elements,” Yarinsky wrote in his essay about responding to the spaces of artists. “Ultimately, everything is shaped by our judgment. We seek a reciprocity between existing and new architecture, a complex layering that balances deference and distinction.” ARO’s stated goal to “restore the sense of awe” was met, as the space’s intensity, previously diminished, now shines brightly.

Celebrations

This careful work, years in the making, is in service of the chapel’s mission to “create opportunities for spiritual growth and dialogue that illuminate our shared humanity and inspire action leading to a world in which all are treated with dignity and respect.” This call to social justice came from the de Menils, and is evident in the dedication of Broken Obelisk, by sculptor Barnett Newman, to Martin Luther King, Jr. A detailed account of this history was published last fall on Cite Digital. Over the years, rallies and gatherings have been staged on the chapel’s grounds, and inside, ceremonies from many faith traditions are regularly practiced. It’s a spiritual vortex of nothingness within the city’s sprawling emptiness. It remains one of Houston’s quintessential places.

Important activations continue: The chapel is where Solange chose to open the film version of her album When I Get Home. Last month, the Rothko Chapel’s 2021 Annual MLK Birthday Celebration featured a lecture from scholar Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor. This spring, an exhibition at the Moody Center for the Arts at Rice University re-stages art by Brice Marden and David Novros that was featured in a 1975 show at Rice, alongside new responses to the chapel from a range of contemporary artists.

A series of events are taking place in the next week to mark the 50th anniversary of the chapel, which was opened on these same dates, February 26-28. On Friday evening a panel discussion about the journey of the restoration features Yarinsky, Sexton, landscape architect Thomas Woltz, and conservator Carol Mancusi-Ungaro. An interfaith service and celebration takes place on Sunday afternoon, and next Wednesday a meditation in the Hindu tradition will be led by Dr. Hansa Medley and representatives of ISKCON of Houston.

On Saturday evening, a program marks the release of Rothko Chapel: An Oasis for Reflection, published by Rizzoli Electa, which captures the chapel’s transformation. An essay by Stephen Fox establishes the architectural context for the chapel, while a text by Pamela G. Smart reviews the landmark’s artistic and ecumenical aspects, supplemented with excerpts from its guest book. An extended portfolio of images by Paul Hester showcases the campus’s improved grounds, new Welcome House, and restored chapel. His expert eye and lens captures the solemn power of Rothko’s interior.

As we await our slow emergence from the pandemic, it’s clear that the dismantling of systemic racism and the seeking of unity must continue. This makes the chapel’s spiritual work more meaningful now than ever.

A version of this article will appear in Cite 102.

Jack Murphy is Editor of Cite.