As one component of the recent efforts surrounding Black Lives Matter, Confederate monuments are again rightfully coming under public scrutiny. Some have been removed in this latest round of reform. A 2016 Southern Poverty Law Center report found that there were more than 100 Confederate symbols removed from public view after a 2015 massacre in a Charleston church. But nearly 1,800 symbols remain intact, according to an update from the SPLC.

In Houston this summer, Mayor Sylvester Turner authorized the removal of two Confederate icons: The Spirit of the Confederacy statue in Sam Houston Park, originally erected in 1908; and a monument realized in memory of Dick Dowling. A statue of Christopher Columbus was also removed from Bell Park after it was repeatedly covered with red paint. Dowling’s sculpture was planned to be relocated to Sabine Pass Battleground State Historic Park in Port Arthur, but for now it will be stored in a warehouse.

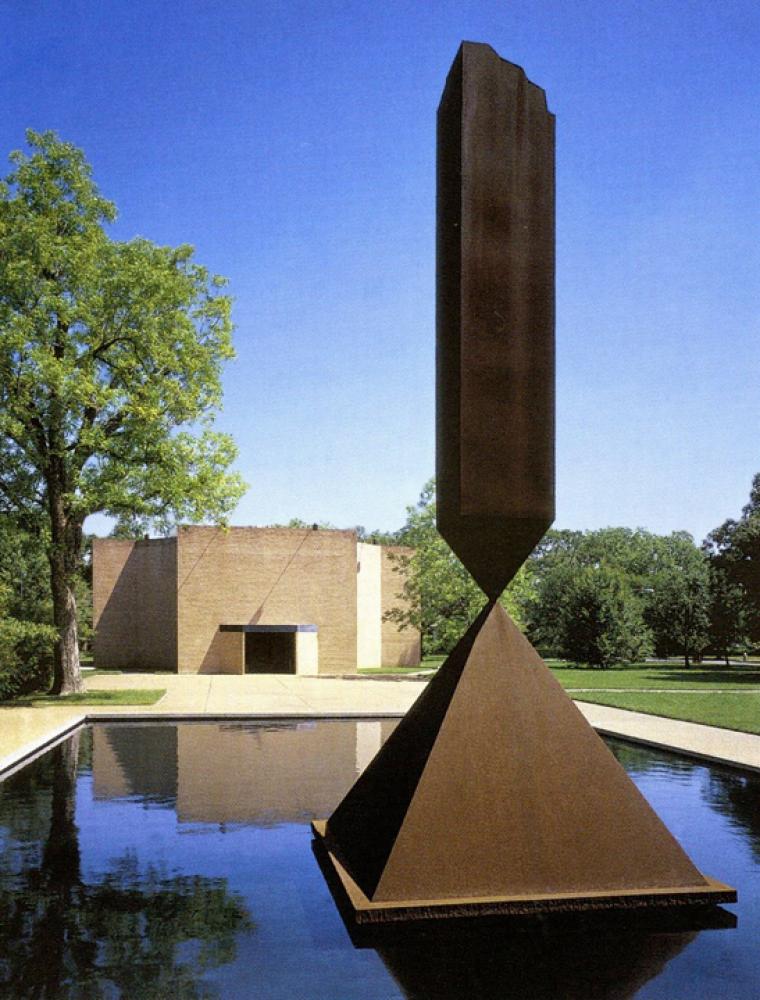

In this text, art historian Amanda Douberley shares research on another moment in the history of public monuments in Houston when racial justice was also at the forefront. Dedicated in 1971, Broken Obelisk has stood in a reflecting pool outside the Rothko Chapel for fifty years as a memorial to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. When John and Dominique de Menil initially offered to bring the sculpture to Houston, however, they proposed neither the dedication to King nor the Rothko Chapel as site. In examining the history of the commission, Douberley reveals how the couple used the sculpture to make a powerful statement about racial justice. Her research also uncovers a little-known connection between Broken Obelisk and the Dowling monument, which may have influenced their decision to make the sculpture a memorial to King.

The story of Broken Obelisk and Houston begins in 1967, when the city became one of two to be awarded a matching grant for public sculpture as part of a new federal arts program. [1] Six months prior to the June 1969 deadline, however, the city had neither raised the matching funds nor selected a site for a sculpture. The Houston Municipal Art Commission (HMAC), which had been charged with administering the grant, turned to arts patrons John and Dominique de Menil for help. At first the couple did not offer matching funds but instead wanted to bring Claes Oldenburg to Houston so he could sketch ideas that could be used for fundraising. Then in March 1969, the de Menils announced that they would give the city the matching funds for the grant on three conditions: “1. That Barnett Newman be the sculptor and that his work ‘Broken Obelisk’ be the sculpture. 2. That a nationally recognized landscape architect such as Kevin Roach [sic] or Louis Kahn design the site. 3. That Market Square be the site for the sculpture.” [2]

The de Menils had admired Broken Obelisk when the sculpture was installed on Seagram Plaza in New York City for the temporary exhibition Sculpture in Environment during the fall of 1967. [3] Earlier that year, Houston had been awarded the matching grant for public sculpture by the National Council on the Arts (NCA). The “Sculpture Project,” later renamed the “Art in Public Places” program, was established to install significant works of art in major civic spaces. The initiative would become one of the more visible signs of increased federal support for the arts and humanities under President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society Program. It also dovetailed with Lady Bird Johnson’s agenda of urban beautification, and with larger nationwide efforts for urban renewal. One condition of the new program in particular would prove to be crucial in Houston: the NCA explicitly forbade the use of the grant for commemorative sculpture of any sort. Rather than a sculptural monument that spoke about the past, the NCA simply wanted to introduce monumental sculpture by the best contemporary artists into the urban environment. [4]

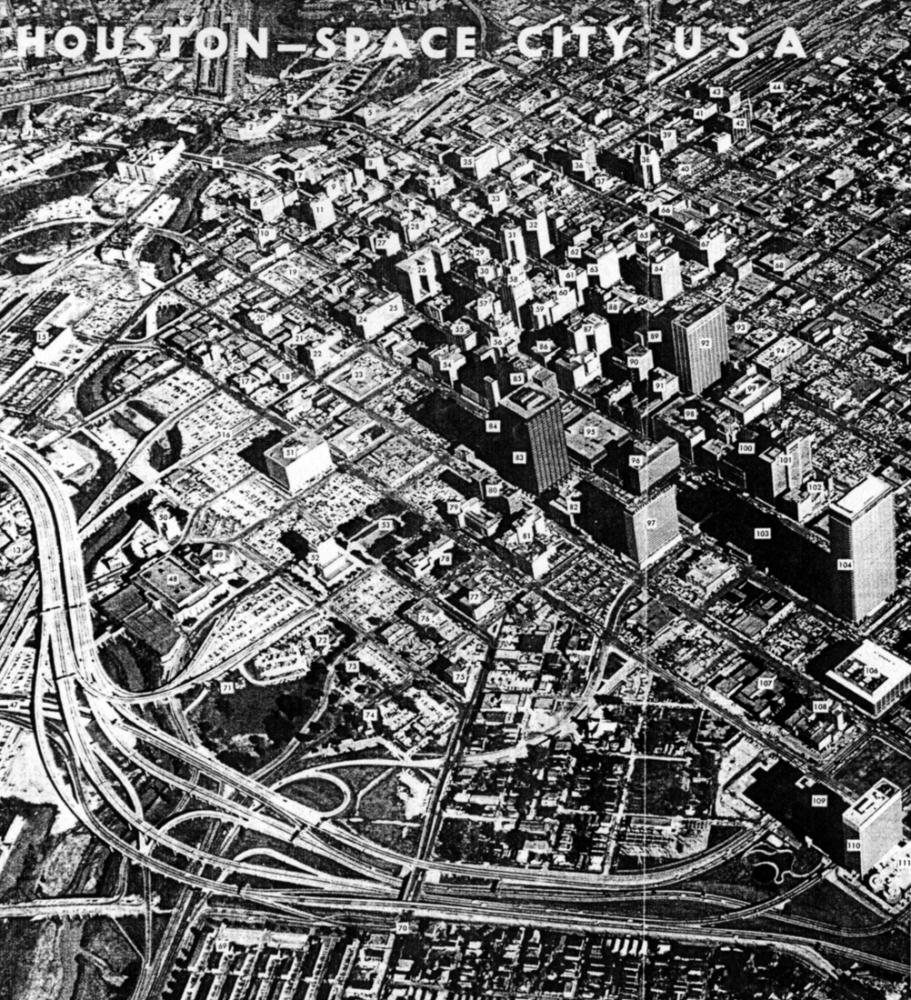

During the 1960s, Houston was embracing a civic image based on an emerging industry. With the arrival of NASA, the Magnolia City became Space City, U.S.A. Arts boosters warned that the city needed to balance its achievements in the space race with excellence in fine arts. To achieve this goal, Houston had formed the HMAC, its first public body concerned with aesthetics, in 1964. This organization was tasked with administering the NCA grant, which included raising the $45,000 matching funds and identifying the site for a sculpture. Then, according to the NCA’s loose guidelines, the artwork would be selected by a panel of experts.

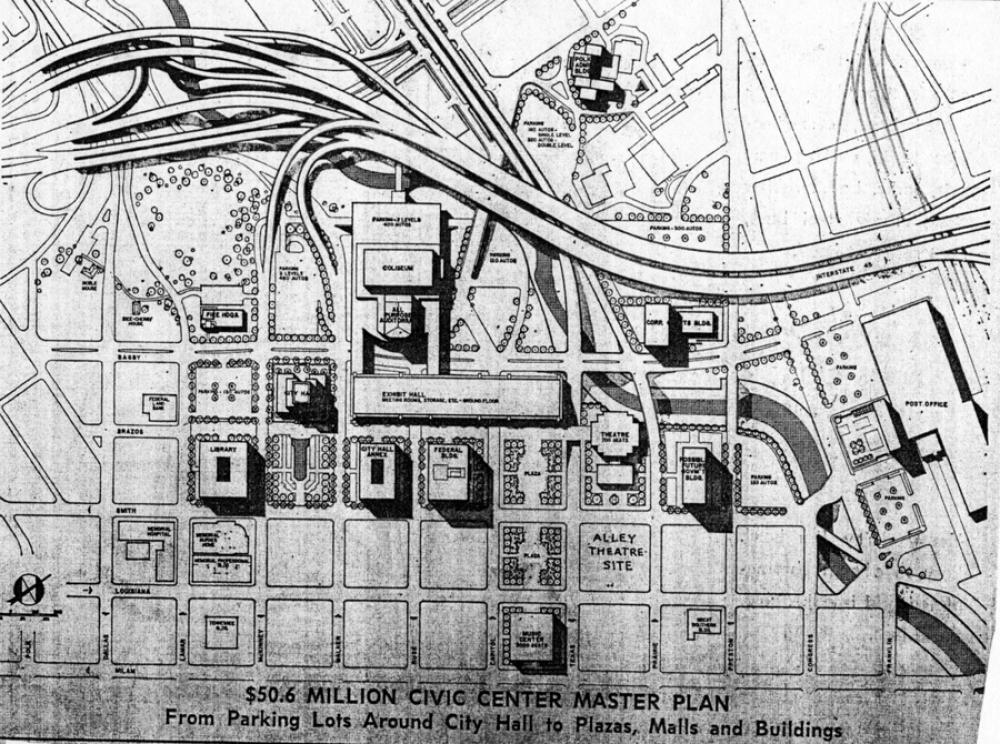

Site selection posed a major problem for Houston and ultimately had an unanticipated impact on Broken Obelisk. The HMAC initially proposed Root Square, a city block on the southeastern fringe of downtown that had been donated to the city in 1923. While art commission members hoped a sculpture would boost redevelopment of the area, the proposal raised serious questions from the NCA. The choice, as chairman Roger Stevens put it, was between trying to salvage a section of the city that was “going downhill” or finding the best place possible in the city from “artistic point of view,” in his words. For NCA council member and Museum of Fine Arts Houston (MFAH) director James Johnson Sweeney, the Root Square proposal merely buttressed real estate speculation. He favored a site in the civic center or near Allen’s Landing, the symbolic birthplace of the City of Houston. Other voices, including landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, spoke in favor of viewing sculpture as a generative force for urban renewal, but Sweeney won out and the proposed site was changed to a location within Houston’s civic center. [5]

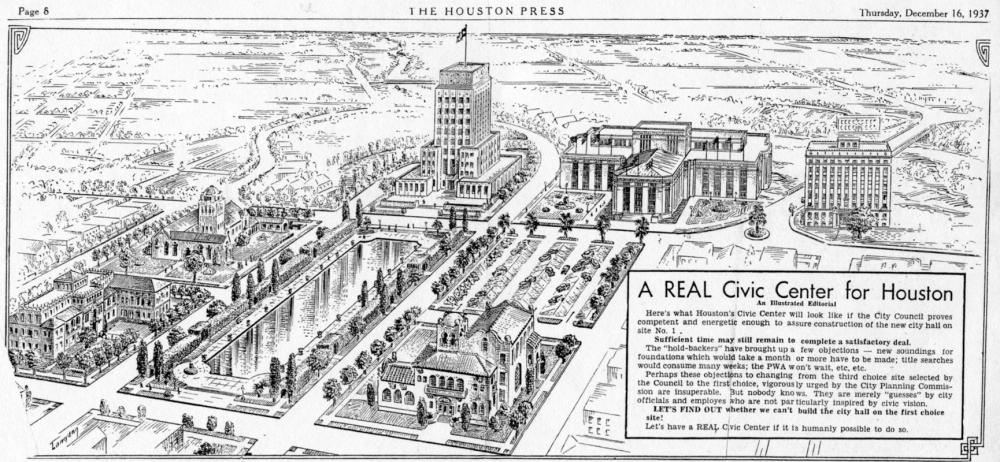

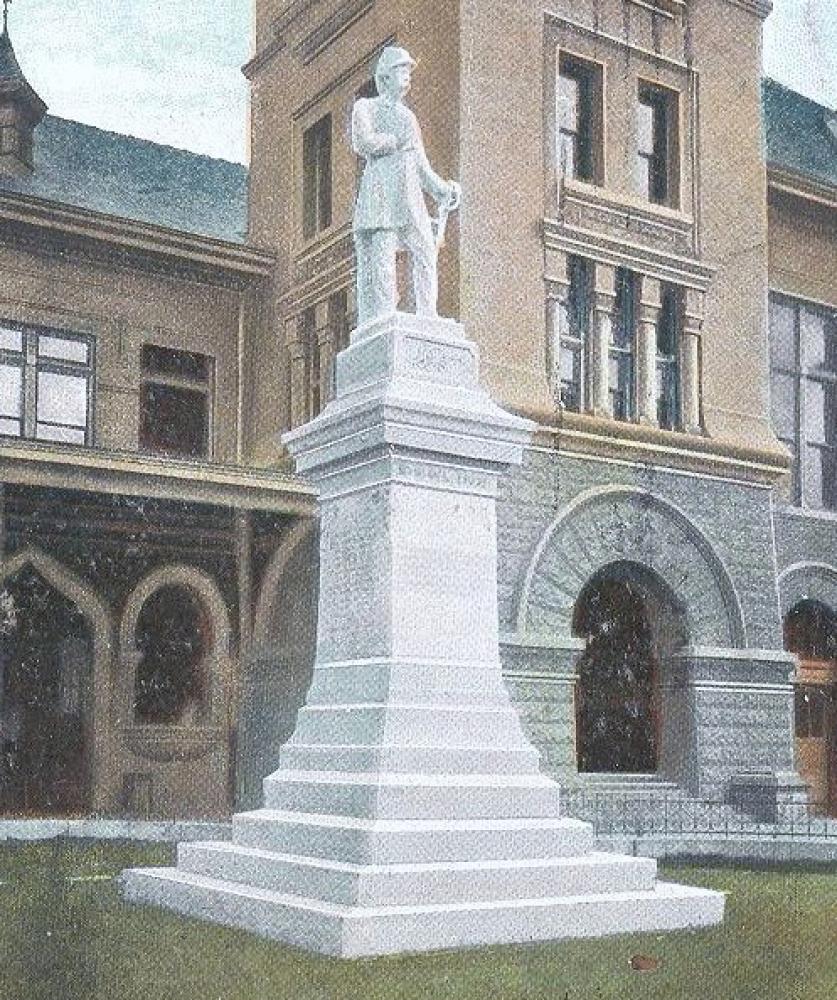

In changing the site, the HMAC did not abandon urban renewal, but instead simply put sculpture in a renewal area. Historically, the center of Houston government and commerce was Market Square, where the fourth and last city hall to occupy the site was completed in 1904 and, in 1905, a statue of Confederate Lieutenant Richard W. “Dick” Dowling was erected. This was Houston’s first publicly funded monument. Landscape architect Arthur Coleman Comey suggested that a civic center be established around Martha Hermann Square at the eastern end of Buffalo Bayou as part of his 1913 report to the Houston Park Commission. In 1926 a public library was constructed in this area and in 1927 voters approved a bond issue to construct a centralized complex of buildings, but a real estate scandal and the Great Depression halted further construction. In 1937, Houston received a grant from the W.P.A. to build a new city hall, which architects realized as an Art Deco office building. That year the Houston Music Hall and Sam Houston Coliseum opened nearby, drawing the performing arts and other forms of entertainment into the civic center. When a consulting firm drew up a new master plan in 1962, they added a convention center and new homes for the city’s premiere theater group, symphony orchestra, and opera. [6] The HMAC’s new sculpture site was the block immediately adjacent to Jones Hall and the Alley Theatre; the new work would be installed above a subterranean parking garage. At the time the HMAC was negotiating with the Houston Endowment, sponsor of Jones Hall, to provide matching funds for the commission; perhaps this is why the sculpture site was moved here. But the deal fell through in January 1969 and the HMAC turned to the de Menils for help.

By the late 1960s, the de Menils had been prominent Houston art patrons for twenty-five years. They were involved with the Contemporary Arts Association (now the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston) as well as the MFAH, using their influence to secure loans for exhibitions and the donation of important works of art. In 1956 they commissioned Philip Johnson’s master plan for the University of St. Thomas and later underwrote the university’s art department, led by their friend Jermayne MacAgy. Following her untimely death in 1964, they decided not to proceed with a proposed university art museum. It was then that the de Menils initiated plans for an ecumenical chapel on property they owned in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood. Dominique de Menil visited Mark Rothko in New York in the spring of 1964 and asked him to create a cycle of paintings for the chapel; that fall, the de Menils formally engaged Johnson as architect (Johnson was soon replaced with local architect Howard Barnstone and then Eugene Aubrey; the facility is currently under renovations led by Architecture Research Office). When the de Menils offered Broken Obelisk to the City of Houston, construction of the Rothko Chapel was well underway. [7]

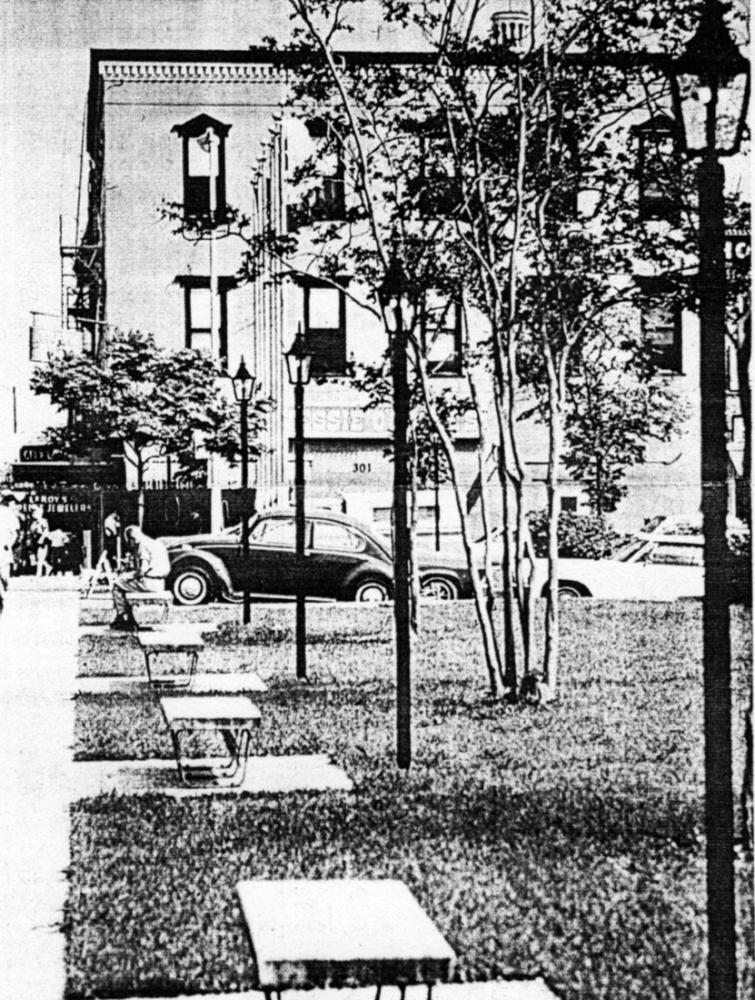

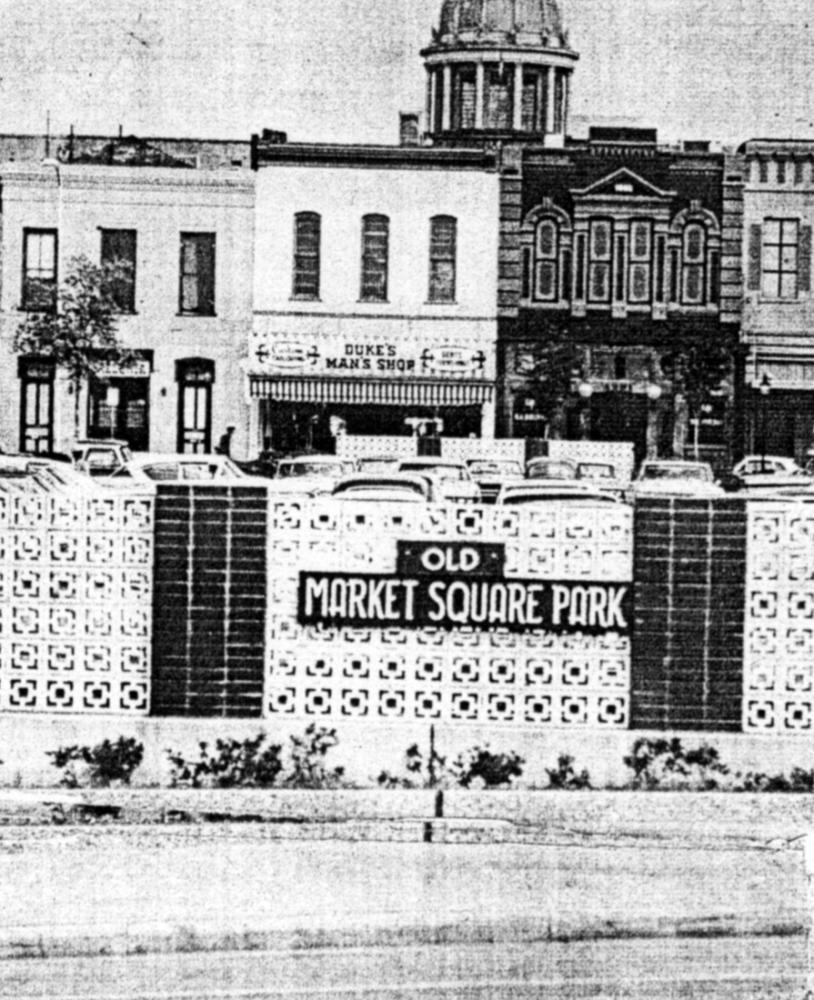

It has been suggested that the HMAC had trouble securing the Sculpture Project matching funds because the city would have little control over the artist selected for the commission. The de Menils solved this problem by making a specific sculpture one condition of their gift. They may have had several reasons for choosing Market Square as their preferred site for Broken Obelisk. Following the opening of Houston’s new city hall at its civic center location in 1939, the Dowling statue was moved to Sam Houston Park, where it stood until it was moved again and in 1958 installed in Hermann Park, where it remained until its recent removal. Meanwhile, preparations were made to convert the old city hall into a bus terminal. After this building burned in 1960, Market Square became a tree-lined parking lot surrounded by some of Houston’s oldest commercial structures [Market Square 1968_1, 2]. By the end of the decade, an eclectic array of bars, restaurants, nightclubs, head shops, and other small businesses had gradually moved into the historic buildings, making Market Square the centerpiece of a burgeoning entertainment district. Tourists flocked to Market Square and to nearby Allen’s Landing, not for its place in Houston’s history, but to gawk at the hippies who hung out there when the Love Street Light Circus Feel Good Machine opened on the top floor (the building, after a renovation by Lake|Flato, is now the headquarters for the Buffalo Bayou Partnership). By suggesting Market Square as a site rather than the civic center, the de Menils indicated their preference for a young, progressive audience over one of businessmen and civic officials. [8]

The de Menils had first considered purchasing Broken Obelisk in 1967 for the University of St. Thomas mall, another gathering place for young people, but balked at the price. [9] During its presentation in New York, critics praised Broken Obelisk for its “inescapable impact or ‘presence’,” which resulted from the obelisk’s “bright orange-rust surface, its twenty-five foot height… and its haughty isolation from traffic and buildings.” [10] The elemental Egyptian forms conjure a long tradition of sculptural monuments, yet the sculpture succeeds in part because it opens up—rather than closes down—meaning. Armin Zweite sums it up nicely:

The pyramid and the broken inverted obelisk afford, in their surprising combination, scope for interpretation, no more and no less. The sculpture is not to be understood as a baroque allegory, in which every detail has a specific meaning, nor is it as empty of content as a work of Minimal Art, nor is it merely a trigger for vague experiences of self under the general heading of the sublime. [11]

Writing in the Houston Chronicle, Ann Holmes even attempted a Space City reading, claiming that “[Broken Obelisk] is a perfect piece for a city in which the probe of the skies is a major factor and the idea of the unfinished upward shaft is almost tailor made.” [12] In referencing the tradition of sculptural monuments, however, Newman’s work easily became a memorial, which ultimately quashed the commission.

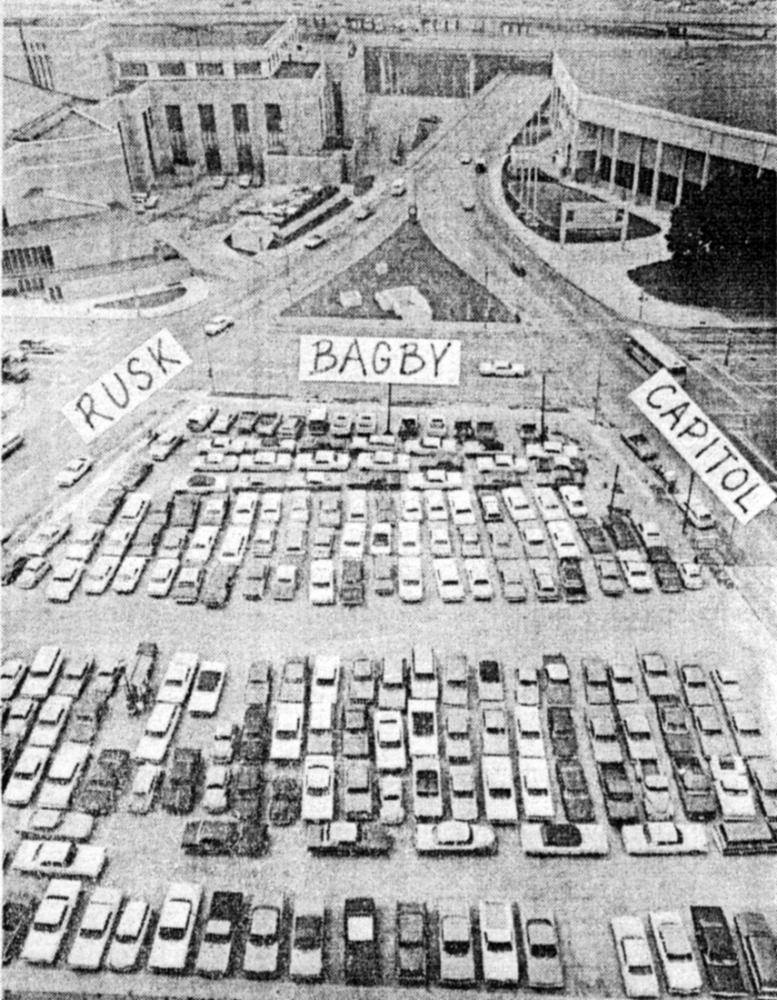

At its regular meeting on March 19, 1969, the HMAC approved the sculpture as “an acceptable piece of art” and, perhaps in response to losing the Houston Endowment’s support, changed the civic center site to a triangular park adjacent to the new Albert Thomas Convention and Exhibit Hall. [13] Here businessmen and civic officials would observe Broken Obelisk on a daily basis as they moved through the civic center; although located only a few blocks away, such an audience was very much removed from the hippies of Market Square. The de Menils rejected the convention center site, which was essentially a traffic island. Then, after several downtown tours with Houston’s Director of Parks, the couple agreed that Broken Obelisk could be situated in front of what was arguably the most important symbolic site in the city: Houston City Hall. With the new site [City Hall 1939] came a new condition from the de Menils: that Broken Obelisk be inscribed, “Forgive them, for they know not what they do.” The quotation was a substitute for the dedication of Newman’s sculpture in memory of King, who was assassinated in 1968. As John de Menil told his friend and interim National Endowment for the Arts director Douglas MacAgy:

We had wanted the monument dedicated to the memory of Martin Luther King and, revoltingly, this created static. The Mayor told us that recently he had been voted down by the City Council on the resolution commemorating the anniversary of the assassination. We reluctantly substituted the quote from the Bible. [14]

Staunch supporters of civil rights in both their public and private lives, it seems the de Menils could not resist the opportunity afforded by the new site for Broken Obelisk to draw attention to an important issue. [15] As part of the Jim Crow South, Houston had integrated its city buildings as late as 1962, a decision driven largely by the competition for the Manned Spacecraft Center. Although the city never experienced the riots that devastated large parts of Washington, D.C., Detroit, Los Angeles, and other cities during the late 1960s, the desegregation of schools was so slow that the federal government had to step in after a decade of stalling on the part of Houston’s school board. [16] The de Menils’ desire to commemorate King put reformers’ efforts in the spotlight. [17]

Though not remarked upon at the time, a Broken Obelisk dedicated to King and standing in front of city hall would have been a powerful corrective, given the history of public monuments in Houston. In 1905 Houstonians had dedicated the eight-foot tall marble statue of Confederate Lieutenant Richard W. “Dick” Dowling (1838-1867), which stood on a twenty-foot granite base in front of the 1904 city hall at Market Square. Sculptor Frank Teich depicted Dowling holding binoculars in one hand and a sword in the other: the former a symbol of the Lieutenant’s watch over Confederate Fort Griffin and the latter of the battle that ensued when a Union fleet attempted to invade Texas via the Sabine River during the Civil War. Since a Union invasion at the Sabine Pass would have resulted in the city’s occupation and potential destruction, many people in Houston—especially Irish-Catholics, who largely paid for their countryman’s monument—revered Dowling as the savior of their city. [18] At city hall in 1969, a Broken Obelisk dedicated to King would have symbolically replaced a monument to a Confederate officer with a memorial to a leader in the civil rights movement.

When the gift was presented to Houston City Council on May 28, 1969, the councilmen seemed baffled by both the inscription, which they suspected was directed at them, and Broken Obelisk itself. The Dowling monument had occupied a recognizable place and imaged a particular incident in the city’s history. What it meant to locate an abstract sculpture in front of city hall was less certain. “Whatever it means, the sculpture could be located in a better place than in front of City Hall,” councilman Lee McLemore told the Houston Chronicle. “People who come down here don’t understand these arty objects. We would be better off with a nice drinking fountain out there.” A drinking fountain in front of city hall would have an obvious purpose while to the Houston City Council, Newman’s sculpture would not. Another councilman grumbled: “Is somebody gonna be down there to explain it to the people?" [19] In this case, the proposed inscription did not help to clarify the sculptor’s intended meaning but instead led to greater confusion. When one councilman suggested that Broken Obelisk be located at Market Square rather than city hall, another redirected the de Menils’ criticism of the council towards the denizens of the hippie enclave and quipped: “That inscription sure would fit down there on the square.” [20] In the end, the councilmen accepted Broken Obelisk with the caveat that another location would have to be found for the sculpture.

Newman had never intended Broken Obelisk as a memorial; he assumed the objections to the dedication were a cover for the Council’s hostility towards the sculpture itself. Yet it was the dedication that effectively ended the debate over Broken Obelisk. As MacAgy reminded the de Menils, NCA funds could not be used to erect a memorial of any kind. [21] The HMAC tried to convince the de Menils to leave out the dedication and requested, “that this sculpture be presented to the people of the City… as an example of pure abstract monumental art of the twentieth century.” [22] The de Menils would not budge.

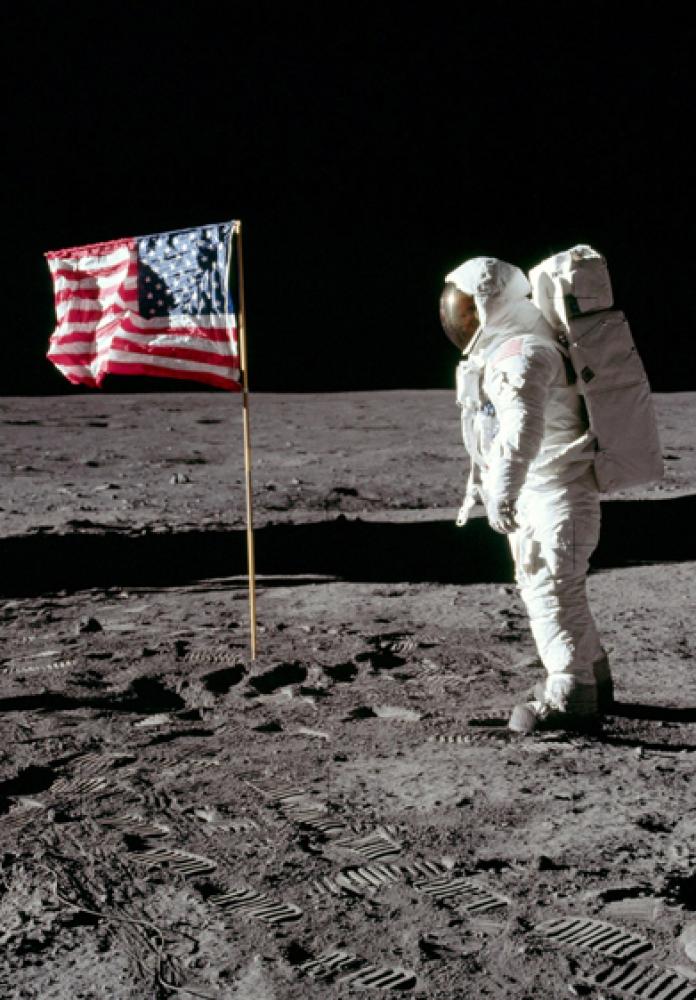

The final skirmish took place on August 20; John de Menil went before Houston City Council and challenged its members to tell him why Broken Obelisk should not be dedicated to King. The council avoided a vote by authorizing Houston Mayor Louie Welch to find out whether the NCA would allow the grant to be used instead for the creation of a sculpture honoring the Apollo 11 astronauts. The previous Saturday, Houston had greeted the first men to walk on the moon with a ticker-tape parade and a free concert in the Astrodome. In a speech, Welch had announced that he would take a city-owned parking lot in the civic center, landscape it, and rename it Tranquillity Park [sic] after the Sea of Tranquility, where the astronauts had landed on the moon. A statue depicting the historic moonwalk would be erected. At the August 20 city council meeting, Welch explained that he had already attempted to contact Felix de Weldon, creator of the famed Marine Corps War Memorial (1954) in Washington, D.C. [23] John de Menil accused the council of racism in the New York Times and the de Menils then purchased Broken Obelisk themselves. [24] It was installed in a pool adjacent to the Rothko Chapel in 1970 and dedicated to the memory of King. There was no chance the NCA would fund a sculptural monument to Apollo 11 and certainly not one by an Academic sculptor. Houston lost the matching grant. [25]

After the announcement of Broken Obelisk’s rejection by the city council, Newman wrote a letter of thanks to the de Menils:

May I now express my appreciation and my admiration for your great courage… When you honored your gift by dedicating it to the memory of Martin Luther King, you also honored my work by rescuing it from the Philistines, who would have destroyed it as a work of art and made it a political ‘thing.’ I hope that my sculpture goes beyond only memorial implications. It is concerned with life and I hope that I have transformed its tragic content into a glimpse of the sublime. [26]

The dedication spared Newman’s sculpture further debate by an unsympathetic city council; instead, it exposed the council’s politics. It is paradoxical that in order to save Broken Obelisk as a work of art, the de Menils made it into a monument. Assigning Broken Obelisk a specific meaning limited the sculpture’s interpretation and made it ineligible for the Sculpture Project; at the same time, it sharpened the criticality of the inverted obelisk, which had made its dedication as a memorial seem appropriate to the de Menils in the first place. [27] It seems fitting that as the golden anniversary of Broken Obelisk’s dedication approaches in 2021, the Dowling monument would be taken down. If Houston’s first public monument did indeed play a role in the de Menil’s decision to dedicate Broken Obelisk to King, then one might ask what new public sculpture their statement will inspire today. [28]

Amanda A. Douberley holds a Ph.D. in Art History from the University of Texas at Austin. Her writing and reviews have appeared in Shaping the Postwar Landscape (Univ. of Virginia Press, 2018), A Companion to Public Art (Wiley, 2016), Public Art Dialogue, Nierika, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art, Art Journal, and caa.reviews. She is a curator at the University of Connecticut’s William Benton Museum of Art, where her focus is connecting the museum’s collections with teaching in departments across the university.

Research for this essay was supported by a 2010-11 Vivian L. Smith Foundation Fellowship at The Menil Collection. Parts of this essay were previously published in Douberley's dissertation, “The Corporate Model: Sculpture, Architecture, and the American City, 1946-1975,” Ph.D. diss, Univ. of Texas at Austin, 2015.

Notes

[1] The other city was Grand Rapids, Michigan, where La Grande Vitesse, a 43-foot tall stabile by Alexander Calder, was installed in 1969.

[2] Katherine Wray to Jean [sic] de Menil, 23 May 1969. Rothko Chapel Collection Box 1 Folder 9: Broken Obelisk correspondence, 1967-1987, Menil Collection Archives, Houston, TX.

[3] Broken Obelisk was fabricated in an edition of two during the spring of 1967 at Lippincott Inc. A third exemplar was fabricated in 1969. By 1971, the three exemplars of Broken Obelisk had found permanent homes: at the Rothko Chapel in Houston; at the University of Washington in Seattle; and at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

[4] The NCA was initially created as an advisory body to the president and Congress with the passage of the National Arts and Cultural Development Act of 1964 (Public Law 88-579). When Johnson signed the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities Act (Public Law 89-209) the following year, the NCA was transferred to the National Endowment for the Arts. For the Art in Public Places program, see John Beardsley, Art in Public Places: A Survey of Community-Sponsored Projects Supported by the National Endowment for the Arts (Washington, D.C.: Partners for Livable Places, 1981).

[5] Proceedings, Tenth Meeting of the National Council on the Arts, 3-4 November 1967, National Foundation on Arts and Humanities, microfilm reel 2, Federal Records, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum, Austin, TX.

[6] My account is largely drawn from David G. McComb, Houston: A History, rev. ed. (Austin: Univ. of Texas Press, 1981). For Houston urbanism during the 1960s and 1970s, see “Office Building Boom is Going Nationwide,” Architectural Forum 118 (May 1963): 114-119; “Cities: Promise and Problems,” Architectural Forum 133 (July-August 1970): 34; “Supercity,” Architectural Forum 136 (April 1972): 25-39; Peter C. Papademetriou, “Architecture in Houston—A Heritage and a Challenge” and Joseph W. Santamaria, “Urban Dynamics of Nonzoning,” AIA Journal 57 (April 1972): 19-27.

[7] John and Dominique de Menil’s myriad activities as art collectors, social activists, builders, and educators are chronicled in Josef Helfenstein and Lauren Schipsi, eds., Art and Activism: Projects of John and Dominique de Menil (Houston: Menil Collection; New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2020). See also Pamela G. Smart, Sacred Modern: Faith, Activism, and Aesthetics in the Menil Collection (Austin: Univ. of Texas Press, 2010).

[8] For Market Square during the 1960s, see Marge Crumbaker, “Old Market Square – by day” and George Christian, “Old Market Square – by night,” Tempo (Houston), 9 June 1968, 7-14, 16, 18, 20-21. Vertical Files, Folder H – Market Square, Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Houston Public Library, Houston, TX. For the hippies at Allen’s Landing, see Catherine Essinger, “Hippie Landing,” Cite 82 (Summer 2010): 28. Vertical Files, H – Parks – Allens Landing, Houston Metropolitan Research Center. Architect Eugene Aubry recalls attending concerts in Market Square area clubs with John de Menil. Telephone conversation with the author, 25 January 2012.

[9] John de Menil to T.B. [Thomas B.] Hess, 19 November 1967. Rothko Chapel Collection Box 1 Folder 9: Broken Obelisk Correspondence, 1967-1987, Menil Collection Archives.

[10] Lucy Lippard, “Beauty and the Bureaucracy,” Hudson Review 20 (Winter 1967-68), 652.

[11] Armin Zweite, Barnett Newman: Paintings, Sculptures, Works on Paper, trans. John Brogden, ed. Jane Bobko (Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz, 1999).

[12] Ann Holmes, “Heroic Storm Centers, Those Public Sculptures,” Houston Chronicle, 10 August 1969.

[13] Katherine Wray to Jean [sic] de Menil, 23 May 1969. Rothko Chapel Collection Box 1 Folder 9: Broken Obelisk correspondence, 1967-1987, Menil Collection Archives.

[14] John de Menil to Douglas MacAgy, 27 May 1969. Rothko Chapel Collection Box 1 Folder 9: Broken Obelisk correspondence, 1967-1987, Menil Collection Archives.

[15] The de Menils’ activism includes the Image of the Black in Western Art, a project devoted to investigating the presence and contributions of Africans and African Americans in Western art. The project is not administered by Harvard University. See Alvia J. Wardlaw, “John and Dominique de Menil and the Houston Civil Rights Movement” in Art and Activism.

[16] William Henry Kellar, Make Haste Slowly: Moderates, Conservatives, and School Desegregation in Houston, Centennial series of the Association of Former Students, Texas A&M Univ., no. 80 (College Station: Texas A&M Univ. Press, 1999).

[17] Acceptance of the dedication to King by Houston City Council was unlikely. Furthermore, the NCA had explicitly forbidden memorials of any sort for the Sculpture Project. Given these obstacles, I wonder if, at this point, the de Menils made a conscious decision to sacrifice the commission to their political statement. After all, their negotiations with the HMAC and city council over their desired Market Square site were at a standstill.

[18] For the battle, see Edward T. Cotham, Jr., Sabine Pass: The Confederacy’s Thermopylae (Austin: Univ. of Texas Press, 2004). A Rice University history class created an excellent website that details the Dowling statue’s place within local histories of the Civil War, https://exhibits.library.rice.edu/exhibits/show/dick-dowling.

[19] “Sculpture Acceptable To City – but Quote?” Houston Post, 29 May 1969.

[20] “Council Accepts Gift Sculpture,” Houston Chronicle, 28 May 1969.

[21] Douglas MacAgy to John de Menil, 28 July 1969. Rothko Chapel Collection Box 1 Folder 9: Broken Obelisk correspondence, 1967-1987, Menil Collection Archives.

[22] Katherine Wray to Mr. and Mrs. Jean [sic] de Menil, 10 June 1969. Rothko Chapel Collection Box 1 Folder 9: Broken Obelisk correspondence, 1967-1987, Menil Collection Archives.

[23] See “Council Turns to Moon In King Sculpture Issue,” Houston Chronicle, 21 August 1969 and “City seeks services of famous sculptor,” Houston Post, 21 August 1969.

[24] Fred Ferretti, “Houston Getting a Sculpture After All,” New York Times, 26 August 1969.

[25] The Apollo 11 monument envisioned by Welch was not realized. When Tranquillity Park opened in 1979, marking the tenth anniversary of the lunar landing, a fountain, distinctive landscape architecture, and a replica of Neil Armstrong’s footprint signaled the park’s commemorative character.

[26] Barnett Newman to John and Dominique de Menil, 26 August 1969. Rothko Chapel Collection Box 1 Folder 9: Broken Obelisk correspondence, 1967-1987, Menil Collection Archives.

[27] Paul Richard, “Woe Follows The Obelisk,” Washington Post, 25 August 1969. Newman’s suggestion that Broken Obelisk is “concerned with life” and “a glimpse of the sublime” is as close as he came to articulating the sculpture’s significance, which has been interpreted by critics and scholars both in terms of Newman’s larger output as well as its historical context. For an overview of Broken Obelisk’s critical reception, see Stephen Polcari, “Barnett Newman’s Broken Obelisk,” Art Journal 53 (Winter 1994): 48-55.

[28] In an interesting twist to this history, life-size bronze statues of Houston founders Augustus Chapman Allen and John Kirby Allen were installed at the east entrance to Houston's City Hall in 2015. Largely paid for by private donations raised by the local United Daughters of the Confederacy chapter, the sculptures were part of architect Joseph Finger’s original design for city hall but were not completed due to lack of funds.