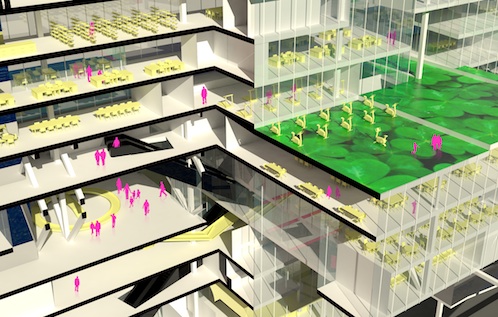

A two-million-square-foot building designed by WW Architecture. All images courtesy WW unless noted.

To introduce himself to the Glasscock School class for “Spotlight on Rice Architecture School,” Ron Witte said in comparison to his wife, Dean Sarah Whiting, his partner in their practice WW and the first speaker in our series, that she’s the more academically grounded and the more articulate before audiences. His historical knowledge, for example, comes second-hand and is “given to hyperbole.” His presentation on October 4---introduced by a survey of the transformation of Paris in the nineteenth century under Haussmann, and followed by a tour through a few of WW’s recent and ambitious designs---indicated, however, that he was only being modest.

Boulevard Sebastopol, Paris, France. Photo from WikiCommons.

The example of Haussmann’s radical excavation of the Paris cityscape served as a model for what Witte describes as a sort of civic hubris. It is all the more remarkable that today we do not tend to think of the city of Paris as an emblem of hubris, given how few towers it has (besides the Eiffel, obviously), how much walking and sidewalk culture it affords, and how moderate in scale are its residential, industrial, and commercial sectors.

Hubris, then, is to be seen in the grand scale of a building site at its initiation or conception. If handled well, once completed, the new structures will settle into their context and be overtaken by the people they serve. They will be normalized, as today are Paris’s famous boulevards, which were carved out of the medieval slums of a dark, super-dense, and congested city. The project was hugely disruptive, even ruinous for many thousands, to be sure, but the city today benefits from greater circulation and access to the modern economy.

As two other historic examples, Witte identified the development plan for the marshland west of Paris, today most everything west of the Place de le Concorde, as well as the massive installation of the Paris Metro, which today enjoys the top ridership in the world among urban transit systems.

Witte is a proponent of the high-density potential of the “Major Activity Centers” outlined in Houston’s proposed new zoning ordinance. He encouraged the class to think about our own city in terms of hubris, to contemplate allowing for disruptions and accommodating the city’s dynamism by means of building projects that may even reach enormous scales.

We then looked at WW’s own projects --- plans that have been submitted to civic planning competitions around the world --- that embrace such a grand scale of vision. We had to study the slides carefully to see all the elements within them, as they encompassed square miles at a time and incorporated dozens of simultaneous elements.

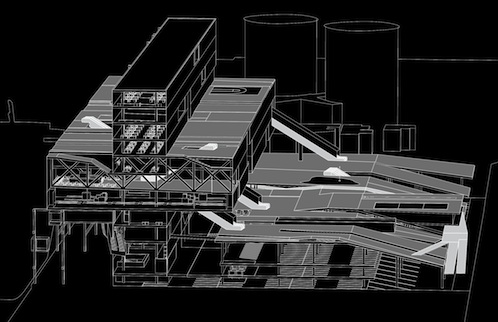

Track Jumping, a proposal by WW.

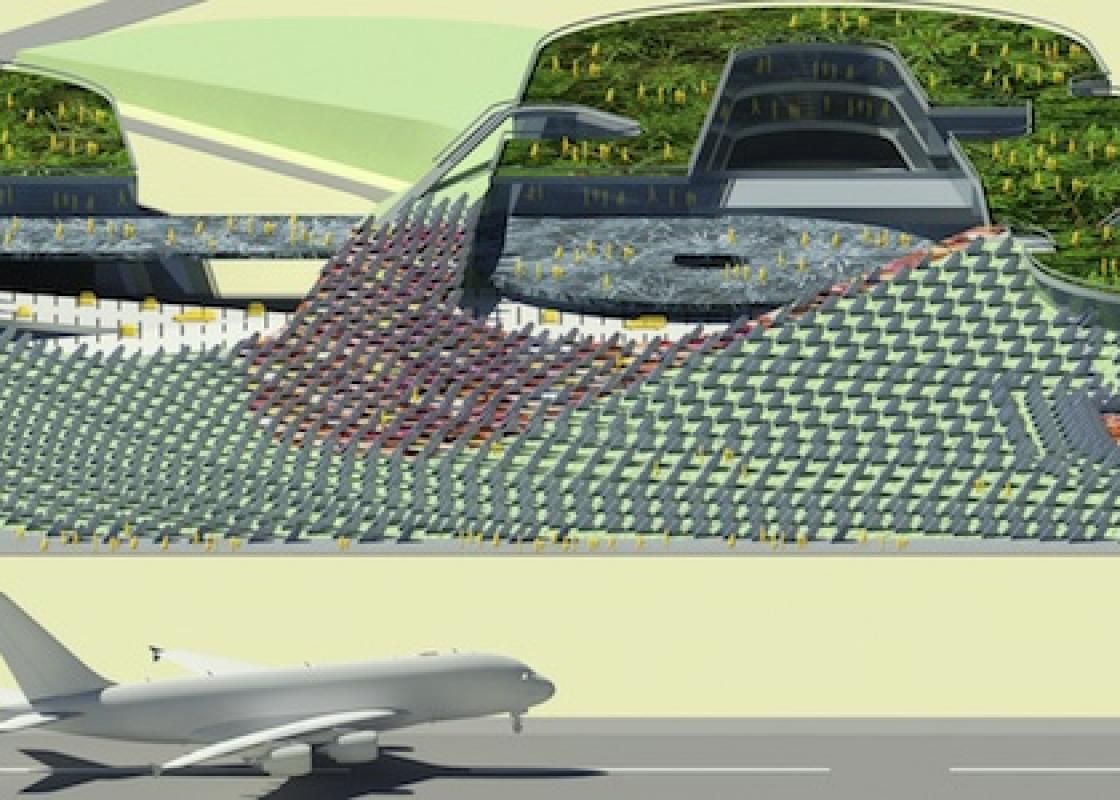

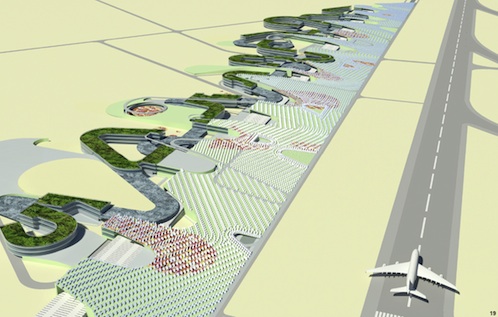

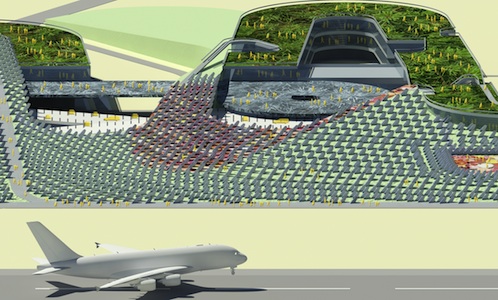

The plans for a 2-million-square-foot building project alongside an airport in the Netherlands, called “Track Jumping,” had to be illustrated in a series of overlapping slides, to illuminate the buildings, the landscape, the parking structures, the walking and biking paths, and the landscaped terraces. These programs overlap and interlink one to another in a manner that seems highly complex from the mile-high, bird's-eye view that is required to see it all at once (and which would be possible from airplanes on their landing approach), but that seems rather placid and easy from ground level.

The challenge of the site was to build a sonic barrier to keep the airport noise from polluting the nearby village. This was accomplished by keeping the buildings low to the ground behind a massive sort of berm that faces the airport. These elements, however, are interwoven, so it would be impossible to suppose that the berm serves a single purpose to shield what lay behind it. The buildings themselves enter the landscape, are buried into it, and curve around to access their neighbors. From the bird’s-eye view, the whole has been described as looking like cursive script, an unexpected but happy outcome for architects who are focused on the “legibility” of their designs.

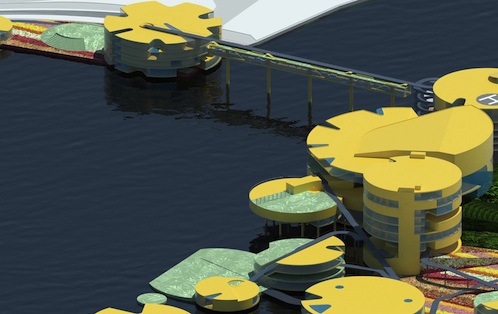

The next two examples of hubristic civic design are made legible by identifying their primary component volumes. First, for a Taiwanese waterfront entertainment district in Kaohsiung, the motif of the circle was deployed in dozens of structures surrounding a harbor. Since circles don’t have sides or corners, they can’t abut, and they can’t close off space. In this 750,000-square-foot program, they overlap with pleasing agility, joined by floating pathways, forming interior and exterior spaces.

Proposal for Kaohsiung Maritime Culture and Popular Music Center.

Proposed Kaohsiung Maritime Culture and Popular Music Center bird's-eye view.

Kaohsiung Port Terminal proposed by WW.

Kaohsiung Port Terminal, section.

Kaohsiung Port Terminal, conceptual drawing.

For the same city, a port terminal was conceived by means of an experiment in combining the two elemental volumes: the vertical slab (as in a day-lit office tower) and the horizontal bar (as in train stations and airports), to create a cruciform. As with Witte’s other examples, the building does not simply fill space: it purposefully activates its surroundings by creating significant relationships with the surrounding environment, taking advantage of the opportunities in its own shape. In the case of the terminal design, called “Sum Plus,” the cruciform allowed for an enormous combination of programs in one place, including freight and passenger loading and unloading, customs and security enforcement, administration, parking, and public recreation, all wound through and over and under itself.

Responding to questions about the seeming complexity in WW’s designs, Witte did not accept complexity as a worthwhile value or aim in and of itself. Witte described the simple boxy buildings by Mies van der Rohe, for example, as highly complex in their organization of space. Relatively simple technologies like those that supported colossal civic structures like the 1890 Forth Bridge, resulted in beautiful “lacey” structures that belie their modest underpinnings. The aim of WW’s design strategies, Witte argued, is instead to find opportunities for simultaneous and overlapping programs in designs both great and small, allowing complexity to emerge rather than aiming for it.

Additions have been made to this 18th-century house in Princeton.

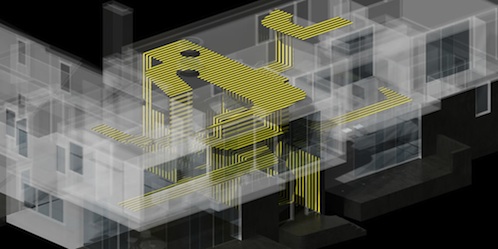

Unfurled box concept for the WW addition.

WW addition to the house.

The final project he showed the class was “Golden House,” this one supported by photographs of the project as it was actually completed. As the last private house standing in what is today a public park in Princeton, New Jersey, the residents of Golden House enjoy sole access to a magnificent outdoor space when the park is closed at night. The building’s earliest structural elements date from the early nineteenth century, and additions were made several times over the decades, including a 1950s structure that WW ultimately removed. In its place, they installed a relatively simple rectangular box, which was then “unfurled” to join inside to outside, and old to new. Witte pointed out the careful use of materials to create seamless volumes and pathways, producing a rich interplay between rooms and open terraces throughout the house, all around the orienting concept of the unfurled wooden box.

As with the enormous civic projects, Witte’s organizing principles were that rich opportunities arise from a structure’s purposeful engagement with its surroundings, and that a simple organizing principle may result in prolific outcomes, which allows a single structure --- large or small --- to accommodate multiple programs at once.