Overland Partners, the San Antonio-based firm, faced a complex task with the Anderson-Clarke Center, the newest building at Rice University. First, it would have to serve more than 20,000 Susanne M. Glasscock School of Continuing Studies students who come to campus to learn languages and practice iPhone photography and brush up on the brief history of the soul.

And it would also have to serve as the first building on a side of campus that's set to grow, as the 2004 Michael Graves master plan shows. That plan --- and, indeed, the need for a bigger building for the Glasscock School in the first place --- coincides with the decade-long tenure of President David Leebron. Benjamin Wermund writes in the Houston Chronicle, “Just about everything about Rice has grown, from its physical boundaries to its student body and its art collection ... . [President Leebron has] worked to connect Rice to the surrounding community.”

Gate 8, where Stockton Drive meets University Boulevard, is being thought of now as a potential gateway for such a connection. Old buildings are making way for new. The Art Barn --- that Howard Barnstone and Eugene Aubry tin-wrapped museum commissioned by the de Menils in the late '60s --- is gone. The Jake Hess Tennis Stadium is next; a new facility has been built on the other side of the parking lot behind Rice Stadium to make way for two high-profile projects: the $20 million Moody Center for the Arts to be designed by Michael Maltzan Architecture, and the opera theater to be designed by one of the firms behind New York City's High Line, Diller Scofidio + Renfro. (Charles Renfro is a graduate of the Rice School of Architecture; read an interview with him by Carrie Schneider on Open House, an experimental art installation in Levittown.)

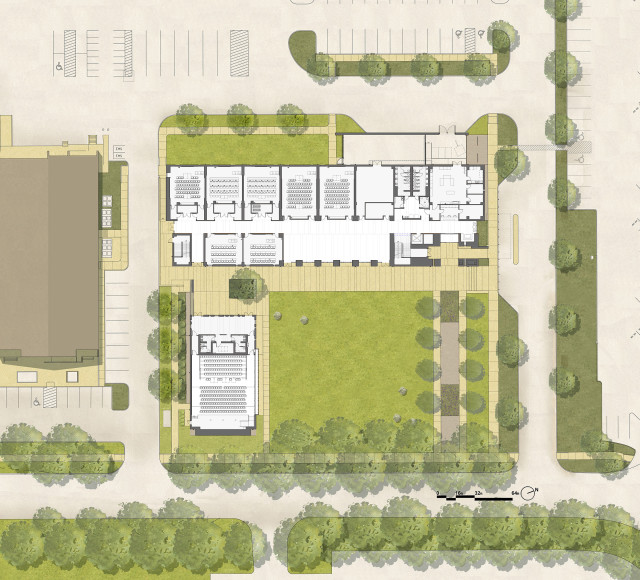

Rising in this context and facing these concerns --- to be both academic infill and new architecture in its own right, to be literal and figurative, a place and a precedent, a gesture connecting the university to the city --- the Anderson-Clarke Center stands up well. The three-story, 55,000-square-foot building includes 24 classrooms ranging in sizes and amenities, several informal gathering spaces, a language center, and detached Hudspeth Auditorium that can seat 225 people.

Overland Partners, which also designed the Lake Plaza buildings and bridge in Hermann Park, risked building something understated on a campus dripping with Byzantine and Venetian details. Overland's Scott Adams explains that the team began working on concepts for the Center as early as 2009. They studied the “long and low” dimensions of the early buildings --- the fountainhead, Lovett Hall, designed by Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson and completed in 1912, in particular.

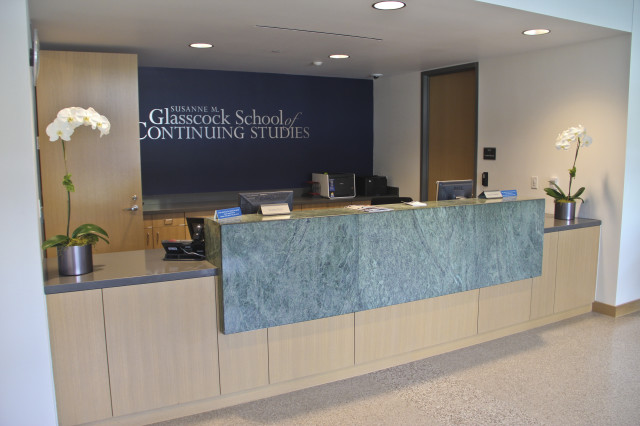

Thus, the same St. Joe brick, limestone, and clay tile finds its way onto the façade and roof of the Anderson-Clarke Center. But there are even subtler nods to history: dark green marble reclaimed from another building on campus was used to cap the welcome desk inside the main entrance; the two stone owls perched in the aluminum composite cubbies framing that entrance were reused, too.

But this is, of course, a contemporary building. Accordingly, the St. Joe brick of its traditionally proportioned façade is divided into bays by painted aluminum composite “popouts,” creating a kind of visual and tactile juxtaposition of the university's past and present. The arch of the main entrance, slid over to the north end of the façade, both recalls and refuses the symmetry of the Lovett Hall Sallyport.

Additionally, the LEED Silver building's interiors use reconstituted wood; the lights are LED. A custom spine-based mechanical system is about a third more efficient than "baseline" buildings. It's the only building on campus that manages its own stormwater --- relying in part on the deeply recessed lawn out front, where the balls of Joseph Havel’s In Play, which appear to be the crumpled false starts of some gigantically frustrated writer, threaten to roll down the hill.

Like the Brochstein Pavilion, the glass-walled atrium creates continuity; the doors can open out and double the size of the space for events:

The building's virtues are subtle and thoughtful. Like the Barbara and David Gibbs Recreation and Wellness Center across campus, designed by Lake|Flato, another San Antonio-based firm, the Anderson-Clarke Center manages to evoke its moment and acknowledge the particular architectural history that precedes it.