Exterior of Torre David, Caracas. All photos courtesy Daniel Schwartz and The U-TT Chair at ETH Zürich

Just a few weeks after winning the Golden Lion at the XIII Venice Architecture Biennale, Alfredo Brillembourg of Urban-Think Tank (U-TT), spoke September 19 at the Rice Design Alliance Fall 2012 lecture series addressing the future of architectural education. (Watch the lecture on YouTube.) With offices in Caracas, São Paulo, New York, and Zürich, Urban-Think Tank is an interdisciplinary design practice dedicated to high-level research and design.

At this year’s biennale, U-TT, along with Justin McGuirk and Iwan Baan, presented Torre David: Gran Horizonte, an installation documenting an unfinished 45-story office tower in the center of Caracas designed by the distinguished Venezuelan architect Enrique Gómez. Centro Financiero Confinanzas (as it was originally known) was almost complete when it was abandoned following the death of its developer in 1993 and the collapse of the Venezuelan economy in 1994. Today, it is the improvised home of a community of more than 750 families, living in an extralegal and tenuous occupation that some have called a vertical slum. Torre David: Informal Vertical Communities, edited by Brillemburg and Hubert Klumpner with photos by Baan, will be in bookstores this month.

Prior to the lecture, Scott Cartwright and Jenny Lynn Weitz Amaré-Cartwright of WAC Design Studio sat down with Alfredo Brillembourg and asked him questions about Torre David and squatting in Venezuela. This post follows on a response to the lecture by Alfonso Hernandez.

Interior of a Torre David dwelling.

Jenny Lynn Weitz-Amare Cartwright (JL): You have done extensive research in the slums of Latin America, Asia, the Middle East. What are some of the trends that lead to the formation of the informal city?

Alfredo Brillembourg (AB): As you probably know we started early as an informal group in 1993, we called it the Caracas Think Tank. It was a walking and talking group of architects and non-architects interested in coming together collectively to talk about the city.

So we began walking the city. We began thinking about it. We began questioning ourselves within the social and financial crisis that Venezuela was going through. What could be done?

Our first extended office partners were actually our gardeners, our drivers; the people who lived in the informal city. They took us in, we went undercover and we began to discover the world that was on the hillsides of Caracas; a world that no one had ever mapped. This eventually turned into a project that became known as the Caracas Case.

The Caracas Case ended in a book called Informal City. And basically it relates the whole story that we could understand of how it was formed, what the growth rates are, what the methods of building this informal city were, and we actually proposed and poked at some solutions on how to retrofit.

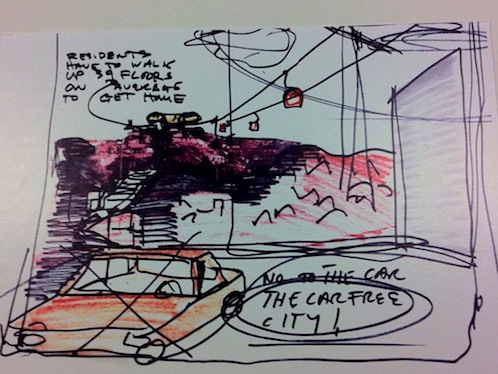

Conceptual sketch of cable car.

JL: What were some of the solutions?

AB: Some of the solutions were built later and over time. One was adding more sports fields (we call that a vertical gymnasium) that we did collectively together with the team. And now not only have we proposed it for Caracas, we have proposed it for Brazil, Jordan, India, and New York, in fact in Harlem. Right now, only three of them are built in Caracas; two of them are under construction, one is finished.

The next thing was transport. How do you get people up these hills when they have to walk on average thirty-nine floors to get home every day? Because Caracas is a city of valleys, rivers, and highways, the cable car seemed like the perfect solution. Not to be used as a touristic element but actually using it as a transport system. We went to the Austrian company Doppelmayr and they financed a study.

That study became a proposal that later reached the governments’ hands, the metro company of Caracas took it on and [President Hugo] Chavez signed the funding and the commitment to it in Austria in a bilateral treaty agreement between Austria and Venezuela.

JL: Now that the Metro Cable is built, how is the city responding to it?

AB: You can see it on the videos that we’ve posted. The one we showed at the MoMa is maybe the most significant one, where people say “now as an old man I can go down to the hospital in 10 minutes.” The woman who’s pregnant walking on the hill on that video says “now I have accessibility immediately to any medical attention and I don’t have to be walking up and down.” You have the children (many of them didn’t even go to school before), now they can go down to the formal city in 10 minutes, something that used to take them 2 hours.

JL: Do you have any plans to build more of these systems of transportation in Caracas, or elsewhere?

AB: Sure. There are plans to build more of them. We’re now looking at a project in Kohima in northern India, which also has a hilly terrain, bordering China. Over there we proposed a huge system of networks because in Kohima monsoons come in terribly and it only has one dirt road. When that road floods, no one can move.

Scott Cartwright (SC): Is it safe and economically suitable to retrofit such areas? Hillside houses continue to spring up in favelas of Caracas. Is the terrain suitable to build?

AB: Yes. Well, Kenneth Frampton, the great modern architectural critic said that the favelas are ”Italian hill towns.” So basically like most settlements, cities began as slums whether it is the old sectors of Paris or London. In fact one of the few areas in Montmartre where the houses were not touched is actually one of the richest and most expensive areas. Why? Because people are looking for that fabric of the city where the city has a kind of pedestrian fabric.

So I think spatially from an architectural point of view the favelas are fascinating. They are more uniform than the formal city. They are built to the same heights. You see them uniformly. They are all these red houses. They use the same unit of construction. So therefore, they know how to build so it’s like Heidegger says, you should build your own house effectively. They build their own house because then you are in touch very much better with your social spatial environment. And that’s what makes favelas so interesting, that they are complex social spatial environments.

Rio has 1,200 favelas, Sao Paulo has 1,100 favelas and Caracas has 60 percent of favelas, or squatted terrain. I have offices in both, Rio and Caracas, and there’s no way that any government can try to erase them or bulldoze them like some clearances of the past. We know the results when that happens, we know the results if you put them on ghetto blocks like in India because that will create more social problems, so the best thing we could do is retrofit.

But within that retrofit, of course, there are areas of mudslides, there are areas of instability, and those risk areas must be cleaned and retrofit. So not all of it can stay, but not all of it has to go. So when we did the cable car we had to clear some sites for the stations. But the illusion that any government has the power to build---in Venezuela for instance, 9,000 housing units [are built] a year---we’re missing two million!

Frequently flooded site in a Sao Paolo slum.

Urban-Think Tank rendering for community center.

SC: Yes, exactly where Haussmannization couldn’t happen. There’s no way that could happen.

AB: Haussmannization is no longer a viable solution. No one wants to be bulldozed out of the house that they’ve been living in for 50 years.

SC: The house that they built themselves.

AB: Yes, that they’ve built themselves and invested over time. That is the growing housing model. I just don’t think a lot of people like it. There are newspaper articles today… I think that one of the old foreign relation officials of Venezuela in a previous government says, “We cannot institutionalize the favela – the barrio, the rancho house.” I think he’s in another time, I think these guys don’t understand that the favelas are here to stay. We have to get more in tune with how people have arrived to the city, and by not having a housing policy, they built their own city because the city was not prepared for them. Old governments didn’t have policies to receive so many people migrating into the city. I think we, as architects and urbanists, have to come to terms with that. And if there is a market for future generations to do a lot of work, it’s going to be in the developing world, it’s going to be in the Global South: Africa, India, Philippines… and South America. These are all areas with incredibly sized slums.

Residents of Torre David do not have use of an elevator.

SC: Your work recently got a great deal of attention after an exhibition and study about Torre David in which your participation won a Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale. Torre David is the most famous occupied office building because it’s the most documented and biggest symbol within Venezuela, but there are something like 26 various commercial buildings, shopping malls, and defunct office towers where the same thing is happening, too. How does that organization within an unfinished building or a multi-story building function? Is it accurate to call them vertical favelas?

AB: Torre David or many of these squats—and it’s not only Caracas that has 26, Sao Paulo has more. They’ve actually demolished the most notorious one in Sao Paulo, but they’ve got at least 10 that I’ve seen in the center of Sao Paulo. But what’s happening? Like Detroit, just to bring it home, is that the center of cities are losing population, and the center of cities are controlled by real estate.

SC: In the United States that happened with post-World War II government policy giving people incentives to leave cities for suburbs, lessening the tax revenue that cities could collect, in which services then deteriorated, thereby pushing more people out of cities.

AB: Right, so they become no-go zones. Downtown L.A. has a whole story about that. Now it’s in revival. But L.A. is unbelievable, you’re next to Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall and just a little bit away you have a huge homeless population. So, we have to come to terms with this in our own cities, in the developing world cities and developed cities also.

But to go back to Torre David, why is it so interesting? We’ve been studying the informal settlements on the hillsides for many years and retrofitting them, but this is the first time we studied an informal settlement in a formalized building: the informal in the formal, and the formal in the informal.

When we do a cable car, a music school, an autistic children school, or a vertical gym, we’re formalizing; we’re introducing formal elements into the informal organic order. And so creating these nodes, these acupuncture nodes, they can maybe give some structuring element with some roads and some cable cars, right? But now we’ve got the reverse, that’s why Torre David is so interesting, where you have the informal that is habituating the formal structures. And we’re not saying that we endorse squatting, no we don’t, but squatting seems to be in a certain way the only possibility that these actual victims of mudslides (that’s where they’re coming from, they’re victims of hill slides falling, they didn’t have any home) and they said, ”Well, this building has been empty for 17 years,” and they organized themselves through a Pentecostal church and started saying ”well, let’s use it.”

SC: The squatting at the Sambil Shopping Mall happened the same way too, right?

AB: No, Sambil is a little different. I think in Sambil actually the government placed people inside, which did not happen in the Torre. Sambil was an official government take-over of a privately owned shopping mall.

SC: …a government expropriation of a private building.

AB: Yes, so the big controversy that’s going on, which is actually fascinating from a sociological point of view, is that we seemed to have touched the nerve fiber in Venezuela’s psyche—or Caracas’ psyche as a city. We touched the nerve because the Torre David stands as [a symbol of] the opulence and prosperity and the failure of an economy as it went from boom to bust. That is why it is such a controversial thing. Some people are lost in the argument around the tower. Torre David is a government building. They thought it was induced squatting. Well no, this was not a tower that was occupied by any government official saying, “Occupy!” No, this is a government tower people occupied to reclaim their right.

SC: So it was the other way around from what those who are upset believe…

AB: It’s the other way around. But the Venezuelan public is in the midst of this civil war (on a philosophical political level) that is happening between opposition and pro-government forces that have taken the tower as a symbol of both sides and that’s why maybe the tower and our argument becomes the common ground. We’ve successfully gotten both sides to comment on it. The government says we must do something for that tower, and the other side says the tower must not be a squat, that this is the failure of government. So they’re both now in agreement that something has to be done. But what happened for 17 years? The whole Chamber of Architects of Venezuela was quiet and silent. You know, what’s going on? It took a biennale to put it there?

View from Torre David.

SC: Actually, not many people really knew about the squat problem at Torre David until the BBC did an article about it in Venezuela.

AB: They did a terrific article! We were actually already working the tower when they went. The BBC and The New York Times wrote about it and Domus magazine later did too. So there have been people picking it up in the last year and a half because it’s so notorious, it’s in the center of the city. But what we did, no one did! We went floor by floor, apartment by apartment. We have more than 500 photos documenting all that… and the book will have I believe 300 photos.

JL: Now that you have done all of this research on the tower and have all of this documentation, what are your plans for Torre David after the biennale? What kind of proposals do you have in mind to solve the problem of squatting?

AB: The tower as we know it is a hot potato. And the tower has an architect---Enrique Gómez did this building. But we believe that the building no longer can be retrofitted as an office block. There are 3,000 families living there, you know, a little town is 3,000 people. So it is a city within a city… and it’s growing every day.

SC: How many floors are occupied?

AB: Twenty.

SC: How many floors are left to be occupied?

AB: Twenty more. But they’ve got people in tents in the upper floors and they actually would like the opportunity to turn this tower into housing. So our proposal in the book (chapter three) shows we retrofit the tower incrementally over time with sustainable solutions. We try to rework the façade with a kind of green façade, aluminum and green façade. We also are looking at where the production of food can be done with lights or lamps, or verticallly. We’re also looking at how to capture rain water on the upper floors. We have also thought that on the top of the building---Caracas has incredible prevailing east-west winds down the center of the valley, very appropriate for wind turbines---we can retrofit wind.

At one point in some article, our curator Justin has used the term “neoliberal dreams.” Neoliberalism failed in Venezuela because it was a moment where in the 90s when Venezuela was trying to build this, during a scandalous banking corruption and crisis. But that neoliberalism, I think, has to be transformed into some new paradigm for the city.

So, let’s take the worst example and turn it into the best. Can we take this tower and turn it into a laboratory and experiment for all vertical towers of the world? And I’m thinking Dubai with all those empty buildings. I’m thinking of India, Jakarta, Bangkok, they all have empty buildings. And what can we do, can they become hubs of energy? Can we bring energy back into the grid by making them capture energy? Because there are times during the day where energy is not being used and you can give it back to the grid. So, we are speculating in our little book. It’s going to be a good one, Lars Müller published it and it is coming out in October. The book is just the beginning of an idea for cities and Torre David seemed to be the most representative.

Torre David.

JL: The original developer, David Brillembourg, was a relative of yours. How has your relationship with him affected the way you approached this project?

AB: I have to say sentimentally; although we’re distant cousins, I actually did know him. We were fascinated by the construction of this tower but it was part of bank failure and later David, my cousin, died of cancer. It became a very sad story. So, yes for me it was interesting to shed a different light on an incredible man who had a spectacular vision for the city.

SC: A failed vision?

AB: Yes, it was failed—but he had a vision. What I find in people today is a lack of vision. So now, a new generation can take his object, and that’s what I’m insisting on, and re-fit it with a new vision. I don’t believe in not having great visions for the city, I’m not a complacent [person who believes] that cities are fine the way they are. I do think that we have to really think because we’re in a last round ecology…what are we going to do with the way we live on this earth?

JL: What about the struggles that people living in the tower go through every day, and the violence that occurs inside and surrounding the tower?

AB: No, no, these are all a myth. If you look at the numbers… First let’s debunk the favela myth, okay? People who live in favelas are no longer all poor… there’s a lot of people that have moved up the ladder that don’t want to move.

SC: Well, there is an entire economy. What percentage of the city is in the informal city?

AB: The majority, the majority world! There is a world out there guys and we call it the majority world, where most of the people living in this world are living with less than $2 a day. One billion are really in critical condition. But two billion are living in impoverished conditions.

So let’s continue. Not everyone who lives in favelas are poor. Number two, the issue that no one has property rights is almost a myth because after thirty years there’s a de-facto right to your property. It used to be a first step housing, a first arrival to the city, but now it has become permanent—permanent arrival. You could say before they didn’t have any services, didn’t have infrastructure but over time—in the last 50 years—they’ve got infrastructure. So, water and a lot of other services have been retrofitted right in. So just by tweaking a bit more and pulling in the appropriate amount of money we could clean it up. A great example is the story of Curitiba, where the mayor, Jaime Lerner, also an architect and later the Governor of the Brazilian State of Paraná, created an incentive by saying, “I give you a bus ticket if you bring down your garbage.” He did not have the money to go up and take the favela’s garbage, but he had busses. So I’m really interested in finding new economic models and incentives.

You’d think, what is an architect doing in this field of social justice and humanitarian aid? I’m doing it for three reasons. One, from a theoretical point of view, I think it’s fascinating. Why shouldn’t architects, like economists, enter into the big problems of humanity? Two, I’m doing it from an architectural point of view because where else can we build the best modern architecture in the world when you can build in the place that has no zoning? Right? Like Houston. And from the theoretical point of view it’s fascinating because it touches upon what we need to do today: come together, bond, create a common ground.

What’s the philosophy behind that? I know Occupy Wall Street and the Occupy Movement have been talking a lot about this. Values have been dissipated and redirected. There’s a new book by Chomsky, if you want to read it, on the Occupy Movement that is quite interesting... He still says there’s a lot of work to be done because the message has to get out to the majority. And then the majority has to understand what is it that we want to change. And then we know President Obama has been trying to maybe get some messages out and unfortunately people aren’t listening or not enough people are listening. We’ll see in the elections coming up now.

Now about the tower, getting back to the myths of the tower. You have 1,500 kids in there, it’s a kindergarten tower! Who’s talking about criminality? There are kids and I think there’s… I don’t know how many mothers. I think there are another 800 women. So of the 3,000 people living there, half of them are kids. This is my point.

So whoever is saying this is the tower of criminals has not gone inside. Well, there is a Venezuelan reporter who went inside just recently and he actually said that what he found was the most amazing organization. It is not a vertical favela, it’s actually a highly organized community.

And that’s the title of our book, Informal Vertical Communities. Now, we’re not saying that this is the way to design cities; we’re just saying, “Let’s study it!”

The sponsor of our book wants to know how do people live in a skyscraper without an elevator. It’s a study.

How are we going to create knowledge? What are universities for? This book is coming out of a university research project. Universities are there to make us think about and to dissipate new ideas. But this story of the tower has really touched some strange nerve and people have not been able to understand it as a research project on an urban level, on an architecture level, sustainability level, or on a social level.

Maybe the only political discourse there is says, “let’s do something right now!” But the truth is no one does anything, they just talk. Talk is easy. Yet we’ve been one year writing a book. So who’s doing the walking?

SC: There was a point in an online Venezuelan newspaper that we were reading a few days ago talking about UrbanThink Tank and the gesture of taking the Golden Lion to Torre David…

AB: Yes.

SC: But the gesture itself is really loaded. On one hand, it is a gesture of empowerment to a group of people that are trying to survive. But on the other hand that gesture will allow it to be politically acceptable for nothing to happen.

AB: We are interested in raising awareness, which I think we’ve done.

SC: Yes, very much.

AB: We’ve raised awareness on the debate on the city. But it is to empower a whole new generation of architects to really rethink the way they’re being taught. To rethink what the role is in their profession. To harp back to the early days when architecture really meant something. Whether it be in the Renaissance when you were the thinker like Michelangelo or Da Vinci. Or whether it be in the early 20th Century with Le Corbusier and his Domino House. In 1917 the Domino House was replacement housing for people after the First World War and he left the walls open because he said, “I don’t care what material you fill the walls in. It can be the ruble of the first world war.” So people forget architects were making their products inclined from a social point of view to change society and to help society advance.

Our only symbolic gesture of bringing the lion to the building meant that we’re going to actually present the book in the building because they helped us so much. It’s the only normal thing we could do---they gave us access and actually they were an important part of our research. So therefore, bringing the lion to the building is actually a symbolic way of saying, ”Listen, we haven’t abandoned you. We still think you’re important. We still think that this fight is not over and someone has to continue it.” It’s just a symbolic gesture to see if maybe we can get more people with the topic. We can’t do it alone.

Our proposal is just a draft. It’s more an engineering proposal of incremental engineering because we don’t touch too much of the architecture. The architecture is there, the floor slabs are there, the apartments are pretty much built out but what's more interesting is to think about how we can retrofit the installations because they don’t have the proper engineering installation.

SC: What hurdles are needing to be crossed in terms of water, sewer, and electricity?

AB: The incredible thing is that this group of individuals were able to rent out the floors and build capital with small condominium fees and actually by renting the parking spaces they were able to raise enough money to pay off the electrical debt of the construction of the building.

SC: And the water debt as well…

AB: And the water debt as well. They actually are capitalistic in the sense that they are producing money, they are making money and they are paying money to municipalities. A building that was not in use now is a productive machine in some way or another, until new solutions are provided.

So let’s call this an interim solution.

Have you ever heard that lots of cities use interim solutions before development later came to a more sophisticated stage? What do you think happened in lower Manhattan? That was squatting my friend. Lower Manhattan was squatted with all the artist lofts. There were illegal squats; they set up electricity illegally. What did it become? The hottest area in all of New York. They later got evicted. What I’m saying is just think about it as an interim use.

Our ideas and notions of property in use are way too archaic, [from the] 19th Century. We’ve got to come up with more flexible systems that do not equate to socialism or anything like that, just equate to realities of our cities.

Who’s got the capital to buy that tower and retrofit it with a five star hotel and office? I don’t know, maybe someone from a Chinese bank or something can do it… that could be a solution. But then with the payments they better build these guys housing.

I know you guys are concentrating on the Venezuelan press. Venezuelan press is important and interesting too but it’s been deviated because we’re in the middle of a hot political battle. All eyes are focused on any news that comes out and must be used for it or against it. This happened to be some big news and [the tower] is an eyesore in the city, so it became a huge political debate.

The value of the research, the value of the proposals, were secondary issues to the political value of this tower. However, look at the international press, look at The New York Times, read the Süddeutsche Zeitung, which is a Southern Germany newspaper, The Guardian, The Financial Times. Those guys get the point but then the Venezuelans say, “oh yeah Europeans get the point because they have a colonial view.” And the problem is by saying that you have a colonial view of us as Indians. It shows you’ve got a complex on yourself, about yourself. It’s sad. What can I say? My country is disintegrating philosophically, politically; psychologically we’re becoming kind of animals in an inquisition.

SC: It’s difficult to place yourself in that argument. Place yourself in that space with those who’ve had so much argument back and forth.

AB: And you could say ultimately that is the battle. The battle is for politics. And I actually believe that it’s that polarization like in Syria, like in Libya, that is leading to a stalemate.

SC: It’s not just there. It’s here too. It’s everywhere right now.

AB: And we thought that the tower could be the common ground, bringing people together. We have yet to see if the exhibit from Venice, Common Ground, actually becomes something more important than just that.

Alfredo Brillembourg was born in New York in 1961. He received his Bachelor of Art and Architecture in 1984 and his Master of Science in Architectural Design in 1986 from Columbia University. In 1992, he received a second architecture degree from the Central University of Venezuela and began his independent practice in architecture. In 1993 he founded Urban-Think Tank (U-TT) in Caracas, Venezuela. Since 1994 he has been a member of the Venezuelan Architects and Engineers Association and has been a guest professor at the University José Maria Vargas, the University Simon Bolívar, and the Central University of Venezuela. Starting in 2007, Brillembourg has been a guest professor at the Graduate School of Architecture and Planning, Columbia University, where he co-founded the Sustainable Living Urban Model Laboratory (S.L.U.M. Lab) with Hubert Klumpner. He has over 20 years of experience practicing architecture and urban design. Additionally, he has lectured on architecture at conferences around the world such as GSD in Boston, AEDES in Berlin, UCV in Caracas, UMSA in Miami, Berlage in Rotterdam, FAU in Sao Paulo, and UCLA in Los Angeles. Since May 2010, Brillembourg has held the chair for Architecture and Urban Design at the Swiss Institute of Technology (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule, ETH) Zürich in Switzerland.

Scott Cartwright & Jenny Lynn Weitz Amare-Cartwright are product designers behind the Houston-based brand wacdesignstudio. Their practice, founded in 2007, focuses on the linkages of art, architecture, and design. This is the third interview they have conducted for the Rice Design Alliance; past interviews include Dutch designer Jurgen Bey of Studio Makkink & Bey and Greg Lynn of Greg Lynn FORM.