Rarely do we see art galleries in buildings designed specifically for gallery use; often they are in generic commercial properties or in structures converted to exhibition space. Brave Architecture was given the unusual task of designing the Sicardi Gallery in Montrose from the ground up. Fernando Brave embraced the project’s blank slate and in his building has crafted a collection of deliberate gestures that accommodate the needs of its occupant. The building, completed in 2012, reads as a carefully assembled compilation of display and operational spaces that intermingle within the overall building envelope.

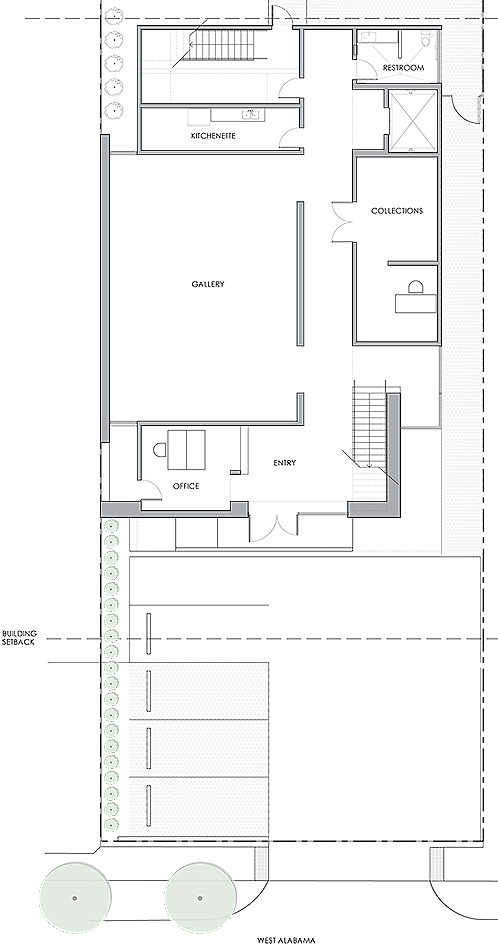

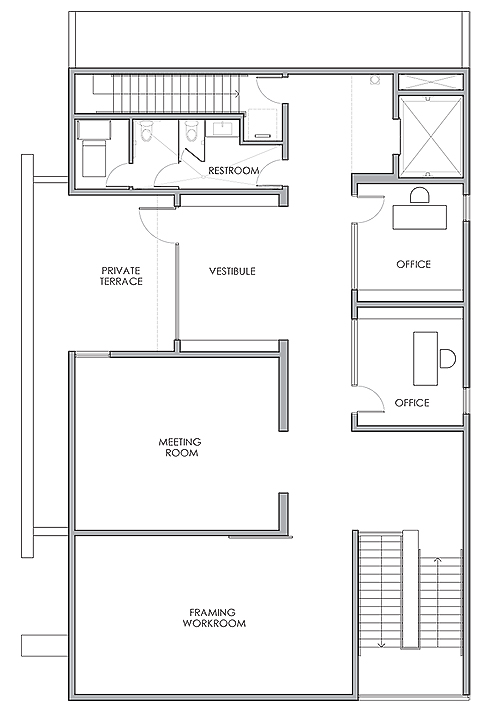

Exhibition space stretches across both floors and takes many shapes, as if the building were assembling a kit-of-parts to maximize gallery versatility. There is a high-ceilinged room for large installations and an intimate alcove for smaller ones. There is a sun-filled niche for those pieces that benefit from natural light, and a room with blackout shades for video art or low-light works. Art that should be viewed from afar can hang at the focal point at the gallery’s far wall, while pieces best seen up-close can greet the visitor in the building’s shallow front vestibule. Sculpture can even perch on the staircase’s substantial central partition. Brave described his approach as a “formulaic response” to both the site on West Alabama and the gallery program.

The Sicardi Gallery focuses on art from Central and South America, both in its choice of featured artists and in its extensive library collections and programs. Laura Wellen, Director of Research and Communications, gave me a tour of the building earlier this month, describing it as a “laboratory” for art. This attitude is carried over in the architecture, as Brave eschewed the traditional “front of house/back of house” distinction in favor of a more blended plan.

As visitors move through the gallery they walk right by offices, storage, and the library, catching a glimpse into overall operations. This benefits the gallery in two ways: (1) the quiet hum of regular office work infuses the space with a sense of activity and warmth, in contrast to the paralyzing silence that often falls on commercial galleries, and (2) the view into research and storage space gives visitors a larger sense of the gallery’s greater efforts, perhaps lending a preview to an upcoming show or a hint of what has come before.

I asked Brave about this, and he noted with a laugh, “We like to see things no one else is seeing, to rummage through storage.” Indeed on my visit Wellen let me browse the hanging racks in the storage room, and it was a highlight of the tour. To unify all these different spaces, a consistent palate of concrete, blonde wood, white paint, and diffuse light allows the art to command attention and blurs the distinction between exhibition and operational space.

Is the building too literal? Perhaps. You can almost hear the conversations between the architect and client as you move through the building. Yet in its clarity there is still room for versatility. Wellen explains, “We still discover new spaces. With each installation we find a new way to use the gallery.” Here it must be remembered that Sicardi is a gallery, not a museum. Though it sits across from the Menil Collection and the Houston Center for Photography, it is in business to sell art. And in business, clarity for consumers has never been a bad thing.

In contrast to the legibility of the interior, the building’s crisp exterior façade is confident, though less direct. The gallery has only two floors, but the exterior reads as a three-story building with a white stucco base supporting a two-story corrugated steel volume.

One large picture window punctuates the gray steel, giving the façade the look of a tightly composed collection of rectangles. As studied as this elevation appears to be, the building still stands quietly, giving the gallery the same architectural strength that many of its neighbors also sport. More specifically, the Sicardi Gallery joins a collection of significant Houston buildings grouped under architect Ben Koush’s term “gray boxes.” In his Arts & Culture Texas article last year, Koush described this coterie, explaining, “[T]hese self-effacing, gray buildings quietly assume their places and provide an intriguing example of a contextually and environmentally responsive architecture for Houston.”

The proximity to the Menil and other arts institutions has allowed the gallery to build a healthy calendar of programs that draw on the foot traffic already in the area. Brave designed for larger events with a second-floor terrace ideal for social gatherings, and with a façade that can easily host outdoor film projections. Planning for a film series is in the works. With this level of activity, the Sicardi Gallery is asserting itself as another anchor in the rapidly developing arts corridor along West Alabama.

Currently, Sicardi is featuring exhibitions of the work of Marco Maggi on the first-floor gallery and Liliana Porter upstairs. Make an effort to visit these during the day if you can; both artists work with delicate materials using meticulous construction, artistic moves that benefit greatly from soft sunlight. Daytime also allows you to capture the big sky through the generous picture window that lights the stairs --- a sight one visitor recently described as “his favorite window in all of Texas.”

More >>>

Read Helen B. Bechtel on the career of Austrian architect Harry Seidler and the Downtown Houston tunnel vision of Bryony Roberts, Rice School of Architecture professor.

Read Ben Koush on gray boxes.