Johnny "John" Eugene Zemanek died at the age of 94 on Monday, April 18. His obituary was written by Patrick Peters with input from Nora Laos, Alberto Bonomi, and Elizabeth Gregory. Look for a review of Zemanek's book about his life and career, Being Becoming, on OffCite in the coming weeks. Below is an interview of Zemanek by his former student, Carlos Jimenez, who is now Professor at the Rice School of Architecture. The interview was first published in the Summer 2008 issue of Cite (75).

John Zemanek, who at 86 remains as curious and vigilant as ever, has for more than 40 years taught design and history to countless students at the University of Houston’s College of Architecture.

I was one of those students in the late '70s. During my years at the university I spent many mornings and afternoons in one of the architect’s earliest designs: the Student Life Plaza (1971), a work of rooted subtlety where water, trees, and paving patterns composed a tranquil space amid UH’s disparate gathering spaces.

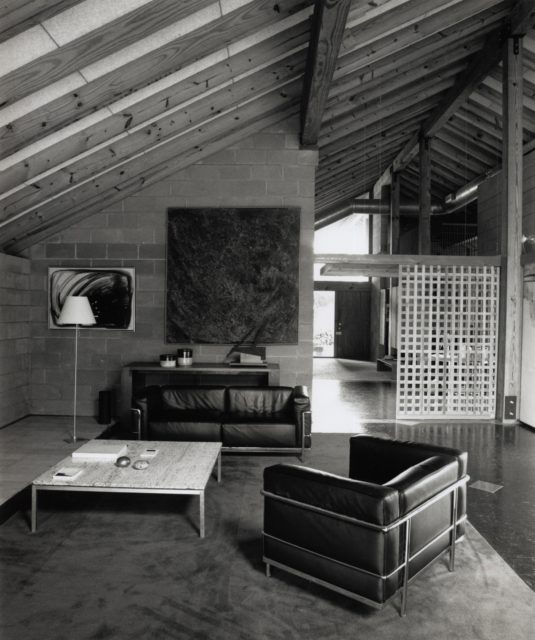

Here I found Zemanek’s consummate care toward the making of place: a sensibility intent on releasing multiple delights for the senses. Similar qualities emanate from the two houses the architect has designed for himself. His first house on Colquitt Street (1965) remains a work of luxurious modesty, a lesson on materiality, and a place where layers of space dissolve into intertwined pauses of nature. Some years ago I wrote about this house, and I titled the text “The Light Between Gardens” in reference to the design’s distinct narrative of two gardens mediated by a delicate and observant architecture.

On a recent spring afternoon I visited Zemanek at his current house on Peden Street. We engaged in an animated conversation about many things, among them a third house he is presently designing for himself, or as he put it: his need for “downsizing.” We discussed the long history of his involvement in architecture.

Carlos Jimenez: You are an architect whose life is marked by a deep passion for design, landscape, and construction. What led you to teach history courses and seminars?

John Zemanek: Your question has a complicated answer. In early 1962 Donald Barthelme was appointed Director of the School of Architecture at Rice. He initiated a series of decisions, which were not much welcomed by his faculty. In the aftermath of the controversy Barthelme resigned. Richard Lilliott, head of the architecture department at the University of Houston, immediately hired him as a full-time professor. In protest, Howard Barnstone, William Jenkins, and Burdette Keeland, who were at the time teaching at the college, walked out on the job saying that they would not teach if Barthelme was going to teach there. This was the first week of classes so you can just imagine the difficulty that created. Lilliott, who had met me through a mutual friend, called me up and invited me to teach a visiting design studio. I remember replying: “When?” And he responded, “Well, right now.”

I was hired to teach design. I had never taught history in my life. I had not even been a history major. As a student I took the standard Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance, and Modern architectural history courses. That was my whole background in the history of architecture. But Lilliott, who was from the English department, didn’t have architectural history in his background either, so he just said to me, “I’ve learned it from scratch; why don’t you try it?” So here I am still teaching history.

C.J.: When I was a student in the late 1970s you also taught a seminar on Postmodern Architecture. I remember that in one of them an incensed Michael Graves walked out of your seminar after you probed him with a particular question. I also remember an enthusiastic Alberto Pérez-Gómez enthralling us with inspired musings on Octavio Paz and architecture.

J.Z.: Regardless of how I came to teach history, my constant desire has been to make it relevant to my students’ future practice of architecture. Since you mentioned Michael Graves and Pérez-Gómez, I should explain that my goal at that time was to show how Graves saw architecture as self-referential, not as an instrument of change, while Pérez-Gómez saw architecture as part of cultural evolution.

C.J.: How do you see the role of architectural history in the education of younger generations of architects today?

J.Z.: History was very important for me as a student. The study of history reinforced my view of architecture and its possibilities in a cultural sense, and therefore it has had a great deal of influence on my deeper search for significance. All significant architects have had an enormous knowledge of history. It is very much evident in their work. With the coming of Postmodernism, architecture was released to deal with history through decorative, spectacular, and dramatic gestures. Mainstream postmodernism declared that architecture is about architecture, not about making statements or expressing opinions.

My view has always been that architecture is about life, that architecture is not self-referential. Nor is art. Architecture and art are instruments of social change, of cultural evolution.

Students today think, why should I even study history? I will be lucky if I can get a job and be an average middle-class person. And to get a job and to hold it I have to be good at the technology of architectural production. I don’t know if today’s students ever think about moral, ethical, or philosophical reasons for doing their designs.

C.J.: Have you seen much of a change in students over the years?

J.Z.: Students today are quite different, let’s say, from students in the early 1980s or in the 1970s. There was an enormous change in world history after the Vietnam War. Education in America took a major shift with the Kent State student massacre. At that point, those of us who were resisting the war in Vietnam, or were supporting the Civil Rights movement and many ideas about democracy and freedom, were taken aback. We thought that we had won, we thought the worst was over and from here on all we had to do was implement what we believed was theoretically right. When it went from theory to practice we thought things would still prevail, but we fell asleep on the job. As we took our victory for granted we began to lose ground. There is a great saying that “the price of liberty is eternal vigilance.” We were not vigilant, and so gradually civil rights began to erode, the poor became poorer, the rich became richer, the middle class diminished in significance until today we are at a point where reversal is almost a fait accompli. We are not a democracy. Why has the attitude changed? Look for instance at this war in Iraq, everybody knows that it is wrong, even the President knows it, but there is no one willing to do anything about it, not that they don’t think that something should be done about it, they just don’t know how to proceed to stop it. They think that since the war is so unanimously rejected that it will automatically go away. Students say, what the heck am I supposed to do about this; no one else seems to think about it.

C.J.: Where do you think this troubling apathy comes from?

J.Z.: Students today are very disturbed about their future. At the beginning of each semester I ask my students to write a short text on “how do you see yourself as an architect practicing, and how do you relate that to your education?” The answers I get are very alarming, you see. Students know that things are messed up, and they know that they are going to end up doing something that is not necessarily architecture but the best they can do. And therefore studying anything else is somehow suspect; it is an illusion to think that it is going to be to your benefit to know history. It is not that they don’t want to learn it, but they don’t want to feel that they have been taken, that after all of that time spent studying history they are not going to need it or that it will not mean anything. So they think, why should I be taken in not once but twice? Like the one-two punch. Is this a kind of cynicism, apathy, paralysis, amnesia? I don’t know. I do know that an understanding of the relevance of history is no longer regarded as a part of the equation or formula in design of buildings.

C.J.: One of the most abiding characteristics of your work is its incorporation of nature and landscape. Can you talk about this?

J.Z.: I grew up on a farm, and I clearly recall my childhood interest in buildings. I remember for instance that when one of my sisters got married they built her a small house on the farm, so I remember all of the materials scattered around. I had never seen lumber before so I was fascinated with its different sizes and with the structural framing. Later I became even more fascinated with how the structural members in one of the barns were not concealed and the singular feeling that their exposed framework gave to the space. I found all farm buildings quite compelling, whether they were located in our own property or in our neighbor’s land. The farm buildings were arranged around a courtyard. We worried about indoor and outdoor space, orientation, drainage, trees, shade, each and all very calibrated for their purpose. There was a clarity in the way the farm worked as a machine of sorts, needing this type of building for this, this structure for that, and so on. The whole thing was also a community. Then there was the larger surrounding landscape; lots of trees, creeks, and rivers, the farms mingled with the prairie and manicured fields to create the gardens that stretched to the horizon. There was never any intention to dominate the landscape; we understood and followed its natural course. The farm buildings were devoid of any ornament or embellishment, their materials were exposed. That is why it wasn’t such a peculiar leap for me to go from the architecture of the farm to modern architecture when I began my studies in 1939. Such buildings as Falling Water and the Barcelona Pavilion, for instance, felt right to me. I instinctively understood them as sophisticated interpretations of the buildings I knew on the farm. I suppose I have never outgrown the indelible experiences of my origin. Of course, with globalization and agri-business that garden landscape in which the family farm evolved has devolved into a rural slum.

C.J.: This appreciation of place is something that springs from these indelible experiences. It clearly influences the way you think of architecture today.

J.Z.: For instance, from where we are sitting right now, I see four old trees. I can sit here and do nothing just in awe of them. These trees tell me where I come from. I have also planted more trees. They are part of a new reading of the site. Existing and new trees converge. When I come home at night I immediately open the patio doors to let the air through. There is not a lot of traffic noise, it is a quiet neighborhood. I love the sounds that come in, the street, the murmuring voices from the street and nearby houses. If the house were closed off none of these conditions would happen. The transitions or thresholds between interior and exterior spaces are always full of possibilities for spatial drama, even if there might not be any trees or vegetation there. Such spaces are contacts with nature and they must not be eliminated, we should always incorporate them in the architecture.

C.J.: After having lived in two houses of your own design, you are now in the process of designing a third house. What prompted this new venture?

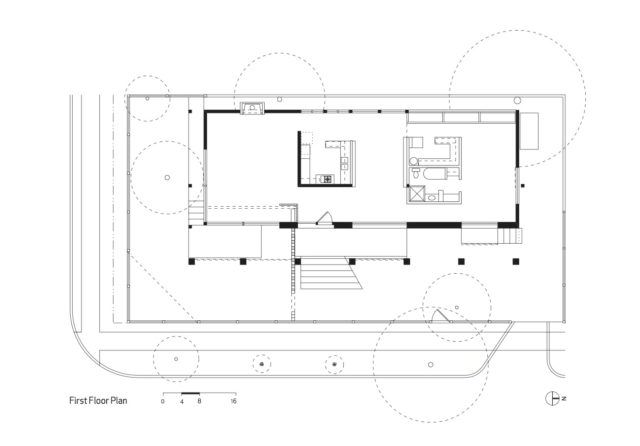

J.Z.: The new house is also sited on a corner lot and it will be a much smaller house, more compact and simpler to maintain. In fact it is only 1,600 square feet. My present house is too big for me. I am downsizing, you might say. But then again these motives might just be excuses. The real reason is that I got to build. The design is a simple rectangular volume enclosed by a surrounding exterior wall right on the property line and lifted two feet off the ground. The house is a single space with two islands for kitchen and bathroom. Even though it is overall a much smaller house I feel that it will be visually more spacious than my current house. From the inside it will all read as one continuous level, gently sloping toward the streetscape.

C.J.: What are your thoughts on the state of architecture today, in particular what do you think of global culture and consumerism as they affect architecture?

J.Z.: Consumerism is not so much about consuming or enjoying as it is about controlling. Consumerism is an instrument of social and political control. You know, our constitution says nothing about capitalism; we have been conditioned to believe that capitalism and democracy are inseparable, but this is not true at all. Advanced capitalism, which is where we are today, is simply another name for consumer culture. There is no cumulative gain in consuming for the sake of consuming — it is an escape from reality, just as it is an escape for architecture to turn to applied ornament or other spectacular devices to justify its existence. Mainstream Americans are addicted to consumerism in order to escape the boredom of reality — reality is that “eternal vigilance” vital to liberty. It is “writ large” in architecture, computer games, iPods, NASCAR ... . To cope with the 9/11 tragedy, the President advised Americans to go shopping, and they did. To democracy, advanced capitalism is the tail that wags the dog. Optimistically, architecture will return to meeting people’s real needs; it will be self-ornamenting.

C.J.: But isn’t this rampant consumerism taking place at a global pace today?

J.Z.: China and India are trying to catch up to where we were 50 years ago. The world is not becoming Americanized, though. It is becoming modernized.

To say that China is becoming Americanized you would have to superimpose American thoughts, values, and patterns on a culture that extends 5,000 years and is so transparent in its determination. Now most Chinese or Indian students are quite determined, positive, confident, and optimistic, they know that their foundation is solid, ancient, and proven. I think the only thing that is going to save this country and put it back on track is going to be a major economic crisis. People are going to have to wake up. You know, during the Great Depression, the western world was separate from the east, but today we cannot do anything without considering the whole world population. In spite of all recent events I am optimistic in the sense that it is possible for someone to rise, an individual, or a group of individuals and say, “Wake up!” Look at what happened four years ago when Barack Obama electrified Americans with his keynote address. You know that this is a mind and spirit that is not going to go away. Now we are in fertile territory for people to realize it is time to wake up.

C.J.: How can architecture operate in a cultural and effective way amid overbearing market forces?

J.Z.: Where architecture has joined consumerism in becoming a marketable commodity, it has abandoned the challenge to make the world a better place. Once the “content” of architecture determined the “form” of architecture. Now architecture’s “content” is the “form” — this is what consumer culture is about. We were not vigilant, we lost momentum. Mies put it quite well when he was interviewed about what his thoughts on Postmodernism were and he replied: “We showed them the way; what the hell went wrong?” Again, we were not alert. And for architecture to be effective, it must reflect vigilance and not be driven by market imperatives.

C.J.: What do you think are the most critical instruments or attitudes that students of architecture should nurture or possess?

J.Z.: In my view for students to learn they should cultivate an attitude of curiosity, a willingness to truly learn. And to do that they must know how to read, speak, and write better. They must accept a common or shared vocabulary of understanding. A student should learn to think in terms of long-term events, long-term experiences, rather than instant gratifications. Students should think in terms of cumulative experience in a cumulative range.

We can’t substitute fragments or bits of information for knowledge. This attitude of curiosity leads to a richer appreciation and understanding of knowledge, life, nature ... everything, especially architecture.