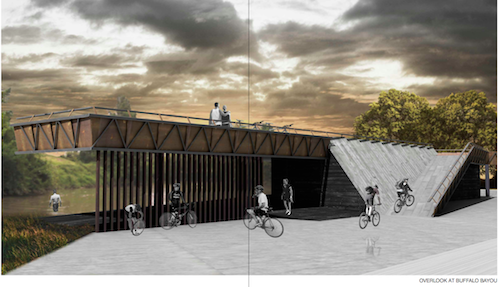

Overlook on Buffalo Bayou. All images by Peter Muessig.

Anyone who’s stalled in Houston’s early evening sea of brake lights might not be inclined to think we have room for an entirely new transportation infrastructure. But Peter Muessig has envisioned a provocative future between the lines of Houston’s urban grid. His graduate thesis for the Rice School of Architecture, “veloCity: Mapping Houston on the Diagonal,” reconceives the Space City and oil capital via the bicycle, which Muessig uses as a “versatile tool for local habitation” to subvert the city’s debilitating trend toward outward sprawl. The proposal won a 2012 Architecture Design Award from both the American Institute of Architects, Houston (AIA) and the Texas Society of Architects in the Conceptual category.

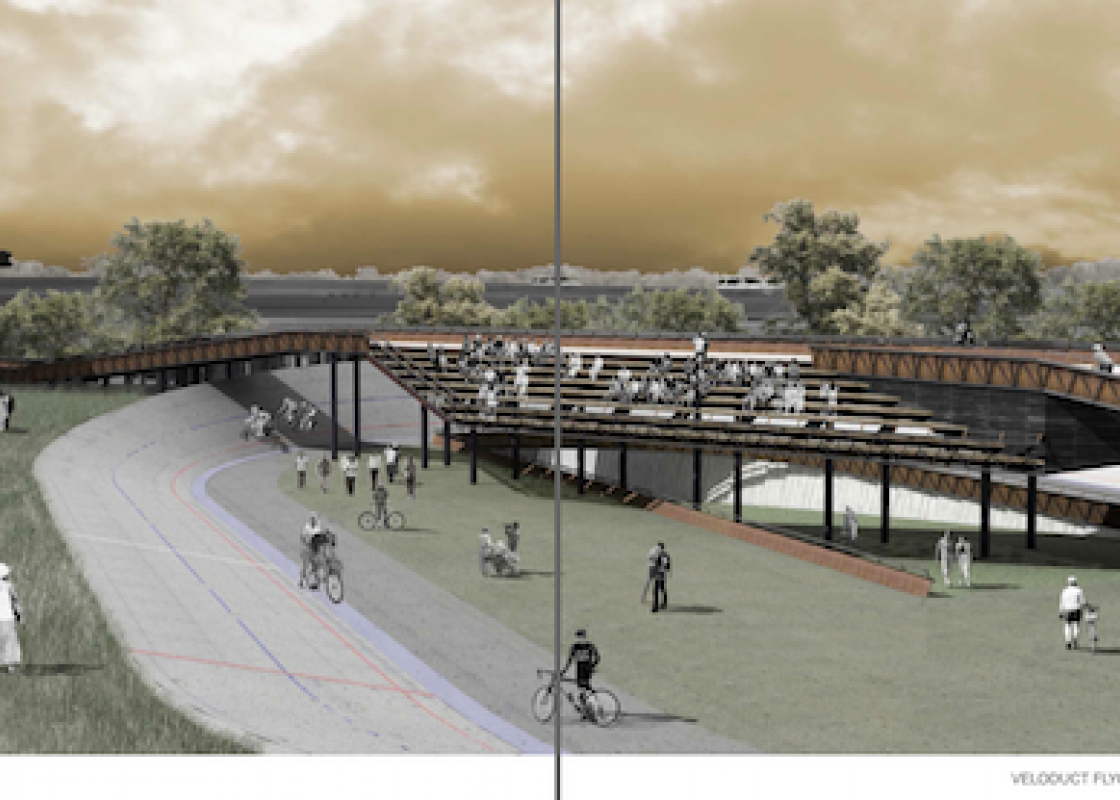

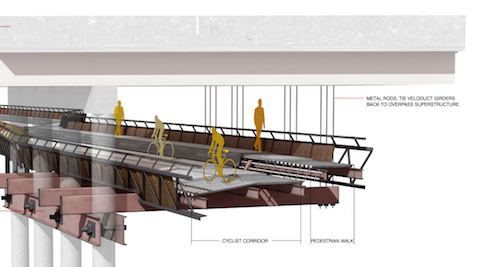

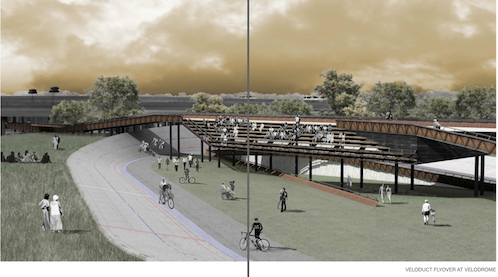

To tackle Houston’s “entwined problems of transit and dwelling, of movement and occupation,” as one of Muessig’s thesis jurists puts it, Muessig has designed the “Veloduct,” a canopy structure that opens uncharted territory to the bicycle, allowing it to cross over (or under) high-speed roadways that would otherwise be difficult to negotiate on two wheels. The Veloduct is, in effect, a versatile freeway for cyclists, with wood-paneled guardrails and a concrete-paved metal pan decking surface system that can accommodate commuters, cruisers, racers, mountain bikers and BMX tricksters. Like a cycle weaving among stalled cars, its network of corridors and pedestrian pathways threads through the spaces between existing structures. Where optimal, the Veloduct adapts these structures into its own form. In variations of concrete, joists, and steel, it can be grafted onto the pillars of freeways, hang suspended by girders, or stand on its own columns.

Map showing veloCity route.

Muessig has mapped his Veloduct across a strategic cross-section of downtown and Buffalo Bayou, where its flexible design can utilize the numerous spaces and surfaces generated by intersecting overpasses—these “vehicular shadows” dictate what its component materials will be at various points, as well as its general trajectory. The infrastructure of the Veloduct aims to stitch together larger infrastructures, tying the city into a more cohesive knot via banked ramps off the main structure that access routes leading to Houston’s various wards. VeloCity is something like a cyclist’s feng shui on an automobile-oriented city, manipulating space to maximize motion. The upshot: if more viable pathways attract cyclists and reduce the number of drivers, more people can live in the city limits with fewer traffic jams.

Overpass diagram.

Muessig identifies veloCity’s most innovative feature in its “looking for opportunity exactly where one would expect to find a conflict.” It allows cyclists to capitalize on precisely those systems that have previously hindered them. That veloCity enables different modes of transport to coexist without crowding each other seems especially critical for Houston, where a lack of safe-passage laws have made many of Google Maps’ bright-green highlighted “bike-friendly” roads anything but. Vehicles of varying speed and means of propulsion can exist on different planes, existing concurrently with but not literally alongside each other. Such paths could connect parts of the city where the streets do accommodate multiple types of users, such as pedestrians, cyclists, buses, trains, and cars.

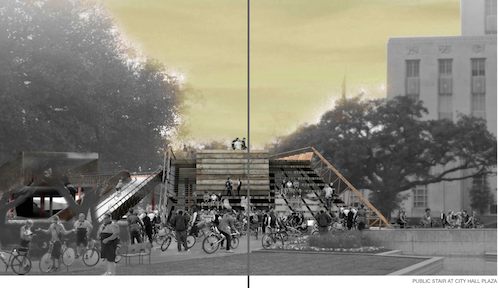

Public space at City Hall plaza.

Veloduct flyover at velodrome.

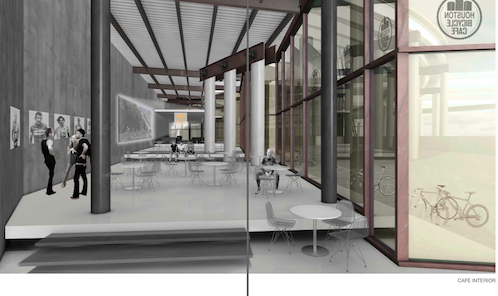

Cafe interior.

Bike polo court under freeway overpass.

In Muessig’s vision, the Veloduct’s weaving through the city’s physical infrastructure enables cycling to weave itself into the larger culture. His thesis is rich with digital renderings of pavilions he calls “programs,” various subcultural hubs like cafes, polo courts, workshop venues, and commuter lockers that occupy the spaces the structure itself generates. He locates the Veloduct’s terminus at City Hall, a symbolic and social site from which citizens can continue to explore their surroundings on wheel or foot, enacting the “raucous parade back into the metropolis” that is itself at the heart of Muessig’s vision.

For the conceivable future, Muessig’s vision remains “conceptual” and is not likely to be implemented. The site at Buffalo Bayou and downtown is already undergoing a major transformation to increase walking and cycling access. Nonetheless, veloCity shines light on how much space the Space City actually has to work with, as well as the potential of cyclists to redefine the city. It begs the question of whether culture will influence infrastructure in Houston’s future, or vice versa. “I see my project as a vehicle to encourage individual initiative,” Muessig says. His project takes the navigational potential of the bicycle as its starting point, underscoring that even without their own freeway, cyclists can transgress the urban grid and chart new courses across the city’s diagonals and blank spaces. If enough continue to do so, perhaps Muessig’s vision will one day come to pass in some form.