The Moody Center for the Arts, the $30 million multi-disciplinary arts building on the Rice University campus, has taken a few well-deserved bows since opening a year ago this month.

It’s a visually striking design — muscular, right-angled and brick; a clever break in form and color from the campus’ picturesque Mediterranean masterplan created a century ago by architects Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson. Architectural Digest last year named the Moody among the nine best new college buildings in world. The California Council of the American Institute of Architects gave the building, a 2017 Honor Award.

Grading the Moody a year later, the building is like a student who demonstrates outright brilliance — only to have the grade pulled down by an incomplete assignment.

Moody Center for the Arts. Lee Bey Architectural Photography.

Moody Center for the Arts. Lee Bey Architectural Photography.

But first, the good. Rice officials made the right move locating the Moody on the western edge of campus, near Entrance 8. That sites the building at one of the university’s busiest access points amid a grouping of buildings that draw in a broad public such as the Glasscock School of Continuing Studies and the Shepherd School of Music. The Moody is brick, but it departs from the brick used across the campus. Los Angeles architect Michael Maltzan wisely rejected the rose-colored St. Joe brick that dominates the campus. He instead chose brick with a magnesium oxide glazing that allows the color of the building to swing from dark blue to purple to gray, depending on the mood of the sun and sky.

“It echoes what we hope will be a really dynamic program,” the center’s executive director, Alison Weaver, said of the brick. “On the inside, we hope to be changing and experimental, and the brick [feels] changing and experimental.”

Moody Center for the Arts. Lee Bey Architectural Photography.

Moody Center for the Arts. Lee Bey Architectural Photography.

Moody Center for the Arts. Lee Bey Architectural Photography.

Moody Center for the Arts. Lee Bey Architectural Photography.

Among the building’s best features: At ground level, the long, prowling two-story structure presents an almost entirely glass face at ground level, with lots of overhead cantilevered spaces that provide shaded areas and walkways for students and patrons to study, relax, and contemplate. A double-height reception area/gallery space is another very nice touch that greets visitors with a soaring inspirational space the moment they enter the building.

There is a wealth of classrooms, studios, offices, and exhibition and maker’s spaces within the 50,000 square-foot building. These spaces with their varying uses are rarely walled off from each other. With glass walls and smart siting, Maltzan has allowed users of one space to freely look and access adjacent spaces, giving the building an unusual openness.

Moody Center for the Arts. Lee Bey Architectural Photography.

Moody Center for the Arts. Lee Bey Architectural Photography.

Moody Center for the Arts. Lee Bey Architectural Photography.

Moody Center for the Arts. Lee Bey Architectural Photography.

A signature spot on the interior is the vertical gallery and seating area on the north side of the building. The spaces is marked by a wide, stepped area that functions as a staircase on one side, linking the first and second floors, and a terraced seating area and gathering space on other. There is comfortable lounge space at the top of the stairs. Big windows allow views toward the campus.

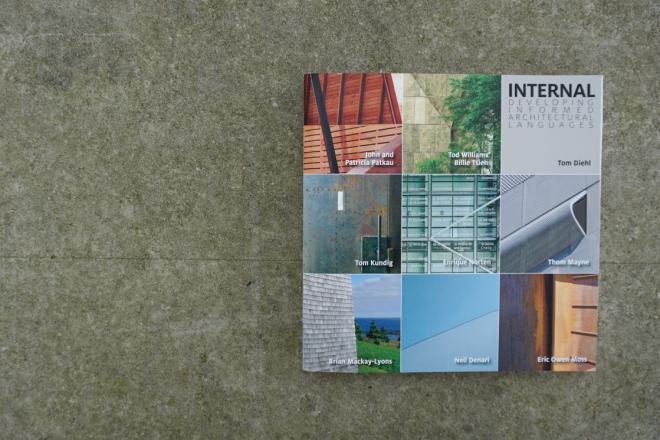

The center is the brainchild of the Galvaston-based Moody Foundation, which approached Rice officials with the idea of building a place on campus for the arts. The building is part of a new class of funder-driven, higher-education arts buildings across the country, designed by top-drawer architects. Among them: The University of Chicago’s Logan Center for the Arts, designed by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects; and Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s Granoff Center for the Creative Arts at Brown University.

The Moody doesn’t quite belong in this class of buildings, due to a few incompletes and unforced errors. Chief of which, the center was designed before an executive director was hired and before the building’s programming could be fully baked. The program itself takes some time to understand. This new class of buildings, and the Moody in particular, seeks to infuse many different disciplines with the arts. Think anthropologists working with photographers, astrophysicists collaborating with sculptors.

Given the challenge of designing a still emerging building type, the choice to build without a director in place to refine the end use violates the spirit of architect Louis Sullivan’s “form ever follows function” dictum, and gives the building a certain vagueness — especially some of the interior spaces. For instance, the 150-seat black box theater needlessly lacks a proscenium stage. The first floor art gallery with its skylight is a true asset, but at less than 3,000 square feet, its feels too small.

That said, the number of art exhibitions, theatrical productions, classes, creative workshops, and social events in the first year is impressive and it all began with a bang when, in collaboration with the Menil Collection, the Moody brought renowned artist Mona Hatoum to Houston as the center's first artist-in-residence.

"The building works well in terms of supporting diverse functions," says Weaver.

A key example of the Moody "mission of fostering interdisciplinary collaboration through the arts" was Olafur Eliasson's Green Light Project. In partnership with Interfaith Ministries, the Moody brought refugees together with students and volunteers to make lamps designed by Eliasson in the central gallery. The artist, a buddhist, and an expert in international relations engaged in a public dialogue in the theater. The interplay of the making, exhibition, and public events was well served by the open and transparent spaces.

Moody Center for the Arts. Lee Bey Architectural Photography.

Moody Center for the Arts. Lee Bey Architectural Photography.

The light-filled coffee shop is among the better spaces in the building, located in a second-floor space that cantilevers eastward from the center. Added to the design late in the game, the coffee shop room could have taken advantage of its jutted-out position to give coffee sippers sterling views of the campus and also of the neighborhood to the west. But the campus view is partially obscured by the oculus — and there are no windows looking to the west.

And what to make of the oculus, the circular, second-story break on the north façade that features a tree-like structural element inside? It’s the building’s most distinctive exterior feature — and yet it seems underthought. Rather than designing what is a hollowed, floorless ornamental space, the architects could have created an actual accessible room that could have allowed interaction with the element as a piece of art, while providing additional elevated views of the campus.

And one hopes the drab, green grass landscape — better suited for a suburban office park — can be enlivened one day with colorful plantings, art and sculpture. Some progress has been made in that respect. Under the direction of Weaver, who came to Rice from the Guggenheim, "Po-um (Lyric)," a sculpture by Mark di Suvero, was moved from another part of campus to one of the lawns outside the Moody.

Buildings appear to be set in stone (or in this case, brick), but they really aren’t. The Moody’s final grade depends on how well the spaces are adjusted and improved as a variety of programming needs come into better focus. Some students improve with time.

Lee Bey is a writer and photographer of the built environment whose work has appeared in Architect, Chicago Architect and the German design magazines Bauwelt and Modulor. Bey’s past positions include five years as architecture critic for the Chicago Sun-Times and a three-year stint as deputy chief of staff for architecture and urban planning under Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley.