The Cultural Landscape Foundation will hold a conference in Houston, March 11-13, called Leading with Landscape II: The Houston Transformation. The expert-led panels and discussions will feature the world-class projects by the leading practitioners working in Houston. This is the second part in a three-part interview that Cite Editor Raj Mankad conducted with Andrew Albers and Ernesto Alfaro, who co-teach a survey of landscape architecture at the Rice School of Architecture. Albers is Vice President at The Office of James Burnett and Alfaro is Senior Associate at SLA Studio+Land. Click here to read Part 1.

Mankad: With major landscape architecture firms coming to Houston and all these big projects underway, and each having their own funding source and their own nonprofit, and their own contexts, the proposals run the gamut. At the Arboretum, you have a reverent approach to ecology. At the Centennial Gardens, you have formal gardens, strong axes, symmetries. With the proposed Botanic Garden master plan, West 8’s design is playful, almost irreverent. Is that a reflection of what is happening in landscape architecture around the country?

Alfaro: I think that range is a reflection of what Houston is like. That same thing happens with buildings. You get such a bizarre collection of eminent architects but it all works somehow. We force it to work. We will force the landscape to work. Houston is such a weird animal. You have the temperature extremes and the dominance of cars. Designers who come here have to contend with many extremes. It forces them to adapt what their normative approaches would be. But that's fine. We'll take it.

Albers: I appreciate having a catalog of incredible design in the city. So many landscape architects are creating so many wonderful spaces.

Alfaro: I am excited to see the transformation of Memorial Park. We discussed how important topographic change is in Houston. That one is going to have a really profound impact on how people use and inhabit the park—both animals and people. It is a very different approach to the park. Having Nelson Byrd Woltz in Houston, for me, is exciting.

Albers: West 8 has proposed a tree pot bridge. Not my favorite idea.

Alfaro: You never know.

Albers: There are definitely commonalities you see today across the projects that you wouldn't have seen so much 50 or 60 years ago. There is an understanding of programming, an understanding of how the spaces will be inhabited, an understanding of maintenance commitments clients are undertaking. I think that there is a—the pot bridge aside—conscious approach to landscapes that will endure. The landscape lasts longer than the buildings. It takes time to develop. There is a long-term view of how the project is going to develop, how it is going to evolve. While that has always been a part of landscape architecture, there's a change in how you think about things like funding sources and evolution of program. Much more than the early formal works of modern architecture or landscape architecture.

Alfaro: There is also a better understanding of how landscape transforms sites economically.

Albers: Yes, today we have real metrics. We always knew that if you had great landscape the architecture would perform better. Everything would perform better. Everybody would be happier. For example, the ULI has investigated what Klyde Warren Park (Office of James Burnett) in Dallas has done. The price of land has skyrocketed, the rents near it have skyrocketed, the number of users coming to that area has skyrocketed. It is a spectacular beacon. What we are doing is going to add so much value, and we need to recognize that the investment is worth it. The return on investment is demonstrable.

Alfaro: That also creates a body of precedents. When you have an ambitious approach to landscape, it is not as scary because people have seen it work. The best example of that is the High Line (James Corner Field Operations, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Piet Oudolf). All of a sudden you get people in different cities saying we want something like that. The same for Atlanta's rails to trails transformation.

Albers: Houstonians’ belief in design is changing with each transformative project. Discovery Green is a great example.

Alfaro: I was there with some parents of my kid’s friends. Normal people. They said, wow, this park is so great, what a transformation for Downtown. When people outside the profession say things like that, you know design is having a profound impact.

Mankad: At a recent lecture for the Rice School of Architecture and Rice Design Alliance, Chris Reed of Stoss started by showing historic images of the Emerald Necklace construction in Boston. He noted that these parks were not only recreational. He showed where light rail and parkways were built, how neighborhoods were formed around the edges of these parks. The whole project was an effort in city-building. I wonder if the way Houston is transforming itself rises to the level of city-building. I worry that there is a limit to what public-private partnerships can accomplish.

Albers: I think you’re right. There needs to be a shift in thinking at a broad level so the public and our elected officials can actually strengthen the scope of landscape projects. Whether we do anything or not, the city is transforming. Our city is growing. Our city is becoming denser. If we try to hold on to the way that things were done without looking toward the future, then we are setting ourselves up for failure.

Alfaro: That’s scary and people don't want to be scared.

Albers: At the end of the 1800s, there were 150,000 horses living in New York. One of the problems of the day was what to do with all that manure. Had someone insisted that we should design the city for the problem of that day, where would we be today? We would have really deep streets.

Our new mayor, Sylvester Turner, has recognized that. He has called attention to the history of our I-10 corridor. We had a problem. We said I-10 inadequately handled the traffic load it had. How did we solve it? The Texas Department of Transportation spent billions of dollars to create the widest highway in the world. And within 10 years of spending all that money, you have recreated the same problem. An even bigger traffic jam. The planning addressed the problem they had and not the problem of the future. You need to address future problems. Designers, traffic engineers, landscape architects, architects, public officials, and citizens who understand this can work together. We need to address the problems of today and the problems of tomorrow.

Alfaro: A tall order.

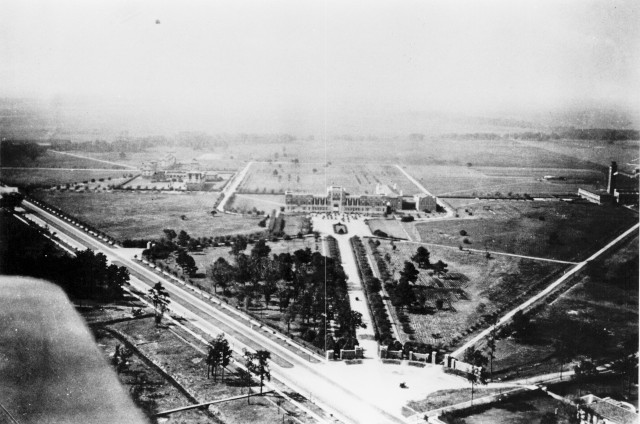

Albers: It takes foresight. Just look at how we’ve changed our city already. If you look at the old photos for the Rice University campus, you can barely make out the tree plantings. Now it's those trees that define the campus and the city. They create allées, axial relationships. The forethought of planting the trees, when you come to Rice, that's what you see. In Houston, the places with the tree infrastructure are where the city is most livable. The least hospitable parts of the city are where the tree program has fallen apart.

Mankad: Yes, those trees define the city. Lars Lerup, the former Dean of the Rice School of Architecture, argued that Houston is not a city at all on the model of the Old World where buildings form processions and enfilades. The overwhelming experience of Houston is of the spaces between. He calls the trees a “zoohemic canopy,” a form of infrastructure. He writes that you come away with “the absurd impression of a city suspended from the treetops from which its cars, riders, and roads gently swing." I love that line.

Albers: If you have an opportunity to get above and look back down on Houston, you can really see that. The city disappears underneath that canopy. It really does make for wonderful spaces.

Alfaro: For all the highways and roadways that cause us a lot of anxiety and stress, once you get up in our offices on the 19th floor overlooking the Galleria looking back Downtown, the overwhelming feeling, the visual that you get, is of a canopied city. It is green. Very seldom does a regular person get the opportunity to become aware of that. Anytime anyone comes up, oh my god, an amazing view.

Mankad: Let’s come back to I-10 and the failure of its...

Alfaro: ... hubris ...

Mankad: … its massive expansion. We talked about designers finding opportunities in the most problematic of sites. What is the opportunity there?

Albers: There is a bottleneck that exists at the reservoirs in the Energy Corridor. The Energy Corridor has been a huge economic driver for the city. And where Eldridge Parkway meets I-10 and then Memorial Drive is at its heart. These intersections are routinely blocked with traffic creating quality of life issue for those who find themselves in the area. Partially in response to these concerns, The Energy Corridor District assembled a team to investigate the future of the corridor. The district commissioned a master plan to address these and other issues.

Connection from Park and Ride in Energy Corridor and Texas A&M Mixed-Use Concept. Courtesy Energy Corridor District.

Connection from Park and Ride in Energy Corridor and Texas A&M Mixed-Use Concept. Courtesy Energy Corridor District.

This master plan documented ideas that could be implemented throughout the city. Very simple ideas that have been around since the birth of cities. Greater connectivity. Parallel roads. The answer is not more lanes, the answer is more options. The plan looks at ways to transform the existing infrastructure that we have—park-and-ride lots and bus lanes. METRO can adjust them to create a system that offers options and that gets people away from the reliance on the single-occupant car.

A circulator bus would move people around the Energy Corridor. If you go to lunch in the Energy Corridor, you have to get to your garage, get out of your garage, drive to where you want to go, find parking. By the time you have done that, it is 30 minutes. Then you have to repeat the whole process coming back. Your lunch hour is consumed by going and coming. So take that out of the equation with a circulator bus.

Instead of driving to the Energy Corridor, maybe you could get on a bus and come to the Energy Corridor, get off at the park-and-ride, get on a circulator bus, and get to where you are going. So it is about making linkages, creating different approaches to the problem of traffic.

Additionally, I-10 serves as a manmade barrier to pedestrians and bicyclists. The Energy Corridor is split between north and south by I-10. The scale is so immense. The plan looks at ways to links these parts of the city back together; for pedestrians; for bicycles; and for alternative transportation.

Mankad: I understand that the big detention basins and drainage ditches scooped out for the I-10 construction could provide more opportunities for cyclists and pedestrians at Langham Park. There is always this positive and negative, this yin yang, especially with hydrology.

Alfaro: If it we were to get crazy about I-10, imagine rail or bus rapid transit going through the center in both directions to get all those commuters in and out, parks on either side, and provide the connectivity elsewhere. You would have these amazing green spaces in the middle of I-10. That's what I would want. Make it a landscape. Use the terrain, use the topography. Screw it.

Mankad: Ha!

Albers: Don't quote him.