Bruce C. Webb is Emeritus Professor, Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and Design, University of Houston.

Dietmar Froehlich’s The Chameleon Effect: Architecture’s Role in Film (Birkhauser 2018) is a pioneering book in the way Susan Langer’s classic book Feeling and Form or Susan Frank’s Literary Architecture or even Charles Jencks’s The Language of Post Modern Architecture are. Like them it’s a book interested in what we can learn by thinking across artistic genres, deconstructing boundaries, and wondering what new understanding comes by conjugating one art form as a metaphor for another. Architecture is the beneficiary (or victim) of a good many of these conjugal relationships: It is frozen music, or inhabited painting, a kind of material poetry, embodied narrative a masque. In The Chameleon Effect architecture finds a near perfect partner in the cinema. In fact, as the book suggests, the two arts may well be destined to meld into one another. Products of the architect’s imagination that are reconstructed in the cinematographer’s imagination create a third artistic phenomenon that Froehlich calls “The Chameleon Effect.”

Architecture enters into this symbiosis as a figure of speech: Beyond requirements of commodity and stability, a building embodies semantic meanings. This happens in a twofold way; elements have denotative meanings identified as functional parts of the architecture code. Peter Eisenman foregrounded these elements (columns, beams, planes, voids) as a stark, self-referential vocabulary to create his iconic, generative houses (House I, II, II ... X). The houses express a formal, transformational grammar, a spare architectural meal for the rational regions of the brain. Building with highly abstract materials that have been denatured by applying dense white polymer paint over plywood, Eisenman erases even the sensual evocation of natural material. But as we see in Chameleon Effect, even this kind of minimalist reductionism never quite escapes from a symbolic or sensuous interpretation.

Of much greater interest in The Chameleon Effect is the way buildings and cities evoke connotative interpretations. Like words in a poem, buildings have the power to engage the imagination with all sorts of interpretations. Architects (and their clients) seek to control the semantic message of their designs (e.g., a bank should look like a bank, a powerful bank should look like a powerful bank; a church is a church). But the freeways of the imagination are unruly. Buildings can be multivalent, fraught with many interpretations; hybrid and overlapping like Venturi’s both-and rather than either-or paradigm. Ambiguity and complexity are engaging qualities both in buildings and in stories. This is the case with many of the excellent examples Froehlich examines where the architectural setting is not simply background but often personified as a character in the film. Watching the way the actors interpret, and interact with a setting can be a learning opportunity for designers.

Like many books with a large theme, the whole story here is not as interesting as the parts. Vivid narrations that parse the architectural settings in various films bring the text to life. Images both of buildings and especially movie scenes reinforce the points and I wish there were many more of them. Setting the interpretive table, Modernism, at least in it’s most extreme and international forms, is frequently used as the haunts for malevolencies and unsettling forces. Heavy Brutalist concrete structures align with totalitarian intrigue of both right and left radicalisms. The code draws on memories of bunkers and other military constructions from World War II and the Cold War, powerful images that persist in the still sizable number of war films (see Jean-Louis Cohen's Architecture in Uniform: Designing and Building for the Second World War). And the puzzling terrible beauty of Lebbeus Woods’ designs that celebrate an aesthetic of violent destruction. Modern war has rooted itself in the psyche where it can be exhumed by film stimuli.

Conversely, virtuousness and security are harbored in the familiar comfort of traditional and rural buildings and tableau reminiscent of Martin Heidegger’s preference for the metaphorical hut or cabin or Gaston Bachelard’s securely rooted house from cellar to garret where the shelter space under the roof is secure. The archetypical modern house with its flat roof offers no such manifestation of shelter. But the interpretation is double edged and the romanticized house once psychoanalyzed as Bachelard does shows the attic and basement are also psychic habitats for filmic horrors, regions of the traditional house that Le Corbusier did away with in, for example, Villa Savoye, which has neither. Leading to a thought, if Domino House had caught on, would domestic horror movies have disappeared for lack of zones of fear and loathing? In the chameleon house on Elm Street it’s a matter of lights, camera, action, and music and who or what goes bump in the

A fascinating analysis of the popular Batman films takes us into the domicile of the cape crusader whose command station is a womblike bat cave, a deco-gothic hideout full of high-tech paraphernalia. Here hidden away from public view Bruce Wayne undergoes his transformation from upright citizen of Gotham City into the more psychologically riddled and fearsome avenger, a transformation occurring almost always at night with a tip of the cowl to his literary Dracula ancestry. The schizoid Wayne splits time with his alter ego on the conscious level of his English-style country estate. After a time, cinematic places begin to construct their own environmental memory. Filled with modern “science” equipment the bat cave is reminiscent of Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory, the quintessential scientific horror laboratory starring bubbling beakers and the wonder of electricity abetting the doctors’ attempt to conquer nature.

The poster for Fritz Lang's 1927 film "Metropolis," designed by Heinz Schulz-Neudamm.

The poster for Fritz Lang's 1927 film "Metropolis," designed by Heinz Schulz-Neudamm.The modern city (New York City and its look alikes) gets ample use as personifications of soulless, indifferent mechanization and mean class rivalry, alleys leading to dead ends where the victims of the architectural monster become lost. Fritz Lang’s famous German Expressionist film, Metropolis, roughed up the image of the modern city in a 1927 allegorical tale of a future dystopian society divided into two castes: the planners who live in the above-ground strata in Gropius style and the workers who slave in a vast underground urban engine room. The Hollywood version of the modern city was never so bleak, but it frequently provided a setting for stories of crime, degeneracy, and hollowness. An anti-city bias that Froehlich traces back to Jeffersonian democracy. America should not follow the European model of becoming a nation of cities Jefferson posited. It was a challenge Frank Lloyd Wright picked up on when he used the Depression as a sabbatical to design Broad Acre suburban-urbanism --- a city even Jefferson might like. The tight amalgamation of competing towers in America’s metropolises made for a claustrophobic city of cabinets. Elevators, streets, alleys, pathways of anxiety could lead to a pot of gold or more often to a dangerous dead end. Shady characters and mobsters favored the anonymity of the city where anyone could hide in the crowd. But Hollywood’s city wasn’t always so bereft. Alongside the city of dismal statistics, there was also the beat of Broadway Boogie-Woogie, a place of energy and entertainment. In Hollywood’s camera eye, as in life, the city breeds and nurtures different cultures: urban cosmopolitans, suburban bourgeoisie, high brows, middle brows, low brows, sensory seekers, and avoiders. Woody Allen’s adoration for the quixotic city has filled the map of Manhattan with unforgettable Woody Allen moments.

If New York is the synecdoche for East Coast style it has an asymmetrical West Coast partner in Los Angeles. Situated between ocean and mountains, the city of the architecture of four ecologies enjoys a narcissistic atmosphere unimpeded by the harshness of winters and old mistakes. It has “every sign of a generic agglomeration … low-rise structures, sprawl and freeways, strip centers and slums.” Set pieces of film, familiar buildings, and landscape ensembles drift in an inchoate fantasy landscape: cool, filled with caricaturist settings, a good place for serial affairs. L.A. has the advantage of being Hollywood’s back lot and so it shows up often in film. (The electronic database IMDb, which Froehlich refers to often, lists around 20,000 films with LA as location.) The ubiquity of LA films has planted the pinball lifestyle as a unique image of American living, a city as chameleon ready for the cameras to roll.

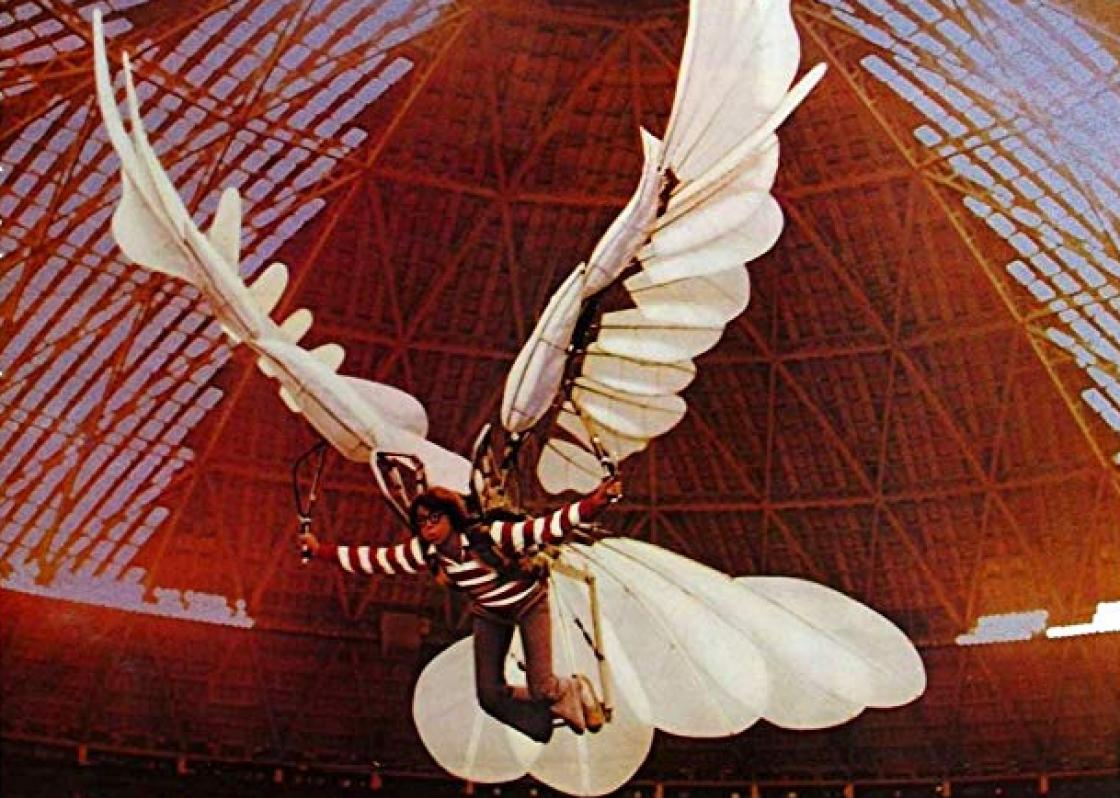

Houston gets brief space among movie cities, as much for its lack of any recognizable features as anything else. Two of its most well-known appearances are as the well-tempered interior of the Astrodome playing itself in Brewster McCloud and as a stand in for Detroit in the twenty-first century in Robocop II. I recall seeing filming of the latter one evening when the action took over several streets around the Wortham Center and produced an all-out street war with real explosions, overturned cars, shooting flames, and waves of machine and bazooka toting actors. It was the most street life I ever saw on a Houston evening. And it showed what the meta-spectacle of creating the chameleon effect looks like. Houston’s proverbial lack of strong urban character, nearly a generic cliché, make it easily adaptable to the filmmakers demand for location. There is, of course, more to it than that, and filmmakers have begun to discover that the city also provides charismatic places and photogenic buildings settled into its messy, ephemeral, freeway landscape.

Froehlich comments on a few other world cities: Berlin (“having been divided for so long, the Eastern part remaining frozen in time, it’s architecture, [is] ... perfect for the portrayal of Eastern European cities”) and Tokyo (a “dream city” of the future).

Science fiction presents filmmakers opportunities to imagine new worlds with their own physical and cultural rules. Filmic architecture still depends on memory for references, but it is in the still unexplored realms of a science fiction world that memory can be challenged and film making reaches its highest aspiration of exercising the imagination on virtual plane. Froehlich concludes by speculating that “[o]ne of the roles of science fiction is to analyze and diagnose the present ... and distill that picture by subtly de-familiarizing it.” Shooting within existing cities, film can “detect and visualize elements of tomorrow." Architecture remains the primary art, with its full range of sensory experience, but a future collaboration of film and computer visualization will inform the construction of a new sense of architectural space and form and help to test out new urban ideas.

I think it’s worth mentioning that this book focuses on popular or mainstream films, a subject less commonly treated to serious inquiry than “artistic” or experimental work. This is to say that most readers will probably have seen more than half the films, many in commercial movie houses.

The author provides a spreadsheet format “Synchronopsis,” outlining a history of significant examples of architecture and film working in tandem, including actors, directors, the architecture involved, and a short narrative of important events at the time. The book suggests to me the possibilities for an ongoing narrative about the subject, perhaps a regular column or section on chameleon effect appearing in professional or scholarly journals. Froehlich’s book has successfully set out the grounding and language for such a literary dialogue, exploring what a thoughtfully observed conjunction of film and architecture can teach us about one another.