One of the first works encountered in Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s, now on view at the Menil Collection through January 23, 2022, is an assemblage mounted on wood. It’s constructed of a man’s rumpled shirt and a circular dartboard “head,” set against a brilliant blue background. The figure’s facial features consist of three darts lodged into the board. Attached to the shirt are an array of mismatched buttons and pressed into plaster are two triggers and their impressions. Closer inspection reveals that the entire surface is pockmarked with tiny holes, a field of punctures that traces the rather imprecise (if enthusiastic) game of darts Saint Phalle had invited the public to participate in when making the work. Its embodied rage and humor, along with its provocative title Hors d’Oeuvre or Portrait of My Lover (1960), offers a perfect introduction to Saint Phalle’s oeuvre, shaped so much by negotiating the terrain of a male-dominated art world that thrived on grand gestures; here that macho expressiveness is undermined by the collectivity of violent, micro markmaking.

Working between performance, sculpture, collage, assemblage, and even architecture, Niki de Saint Phalle (1930–2002) created an expansive body of work that testifies to her unwillingness to be typecast. She was the only woman in the Nouveau Realiste movement, but she insisted on her individuality, apart from any group, even as she collaborated frequently with her male colleagues. Though the exhibition is constructed around a compact timeline, it situates Saint Phalle’s generative impulse across and between mediums as she pressed beyond both aesthetic and social boundaries.

In the context of the Menil Collection’s holdings, Portrait of My Lover also conjures Magritte’s use of the anonymous bowler-hatted man, an archetype who too represented the dominant (patriarchal) world view. Surreal affinities abound throughout the exhibition, thoughtfully curated by Michelle White, Senior Curator at the Menil Collection, and Jill Dawsey, Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, where the exhibition will travel. Formally similar to Portrait of my Lover, Tu est Moi (also 1960), on a nearby wall, evokes a landscape with a painted red sun rising above a plaster lunar surface embedded with ominous-but-mundane objects: a steel gear, razor blade, rope, fork, scissors, knife, hammer, and toy gun. Featured in the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition The Art of Assemblage in 1961, Tu est Moi was shown in the context of Surrealist production (including Surrealist-adjacent artists like Joseph Cornell) and alongside American artists Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, with whom Saint Phalle would soon collaborate. Tir de Jasper Johns (1961) in the next room is both an homage to and a playful sendup of Johns’s groundbreaking work in assemblage, which drew upon the Surrealists’ insistence that everyday domestic objects were inherently peculiar and quite possibly subversive.

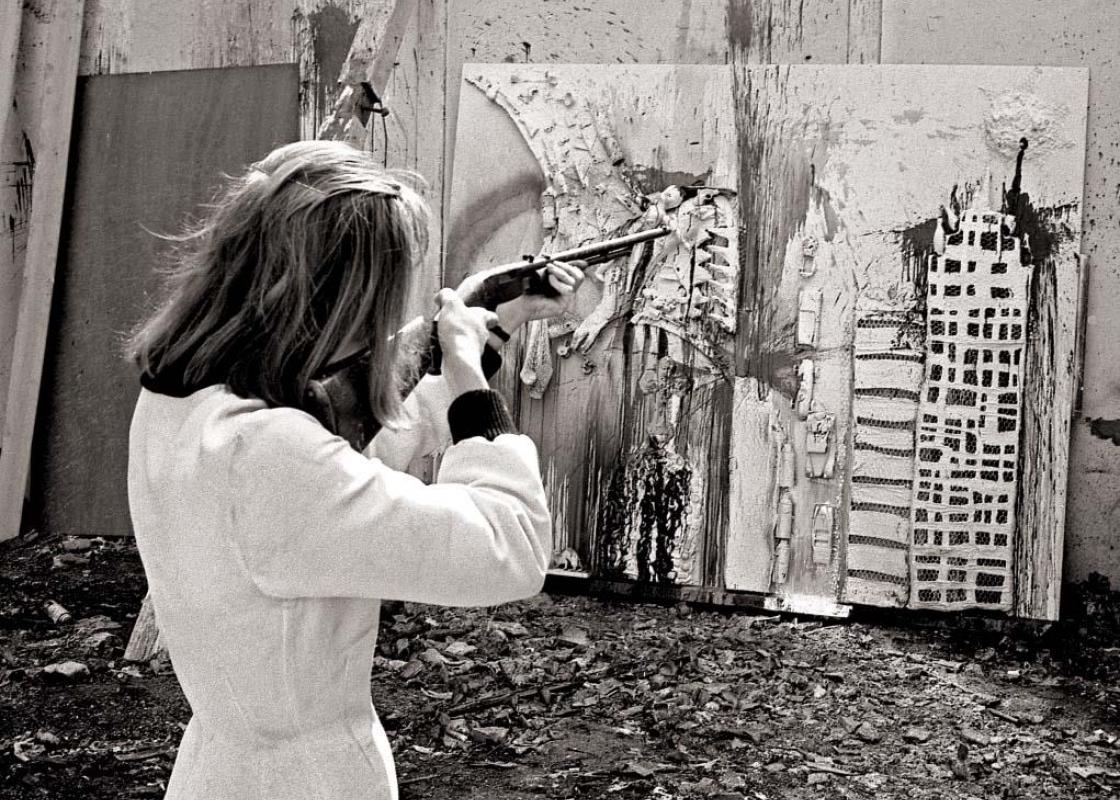

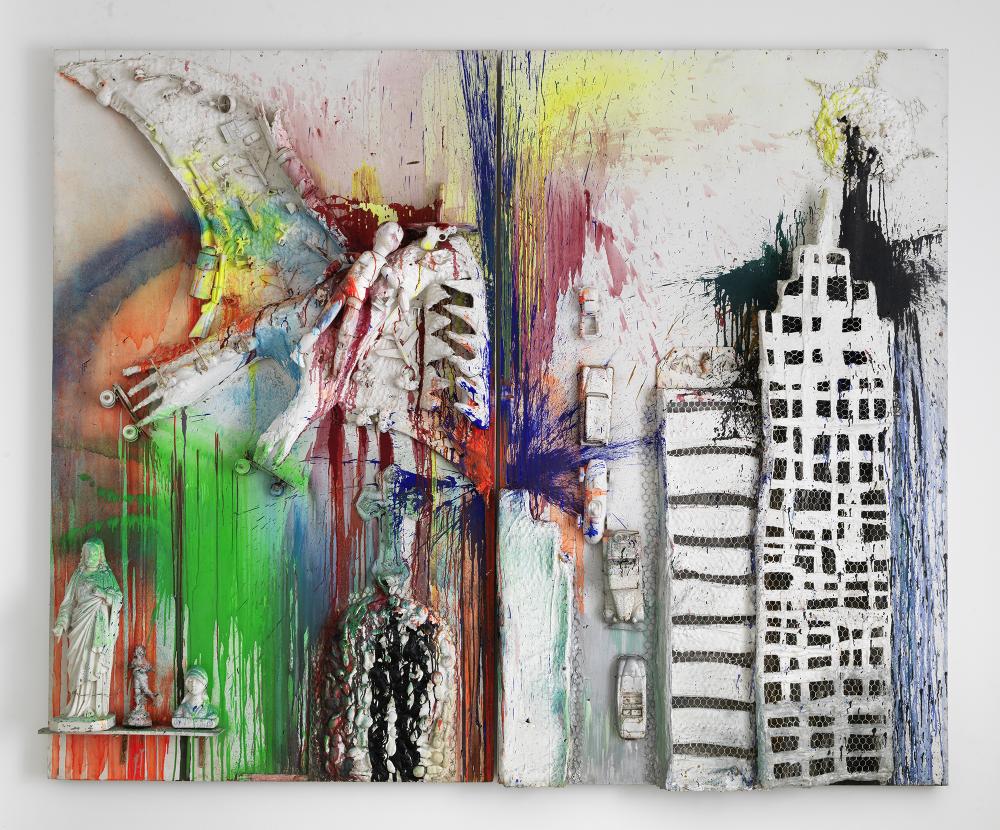

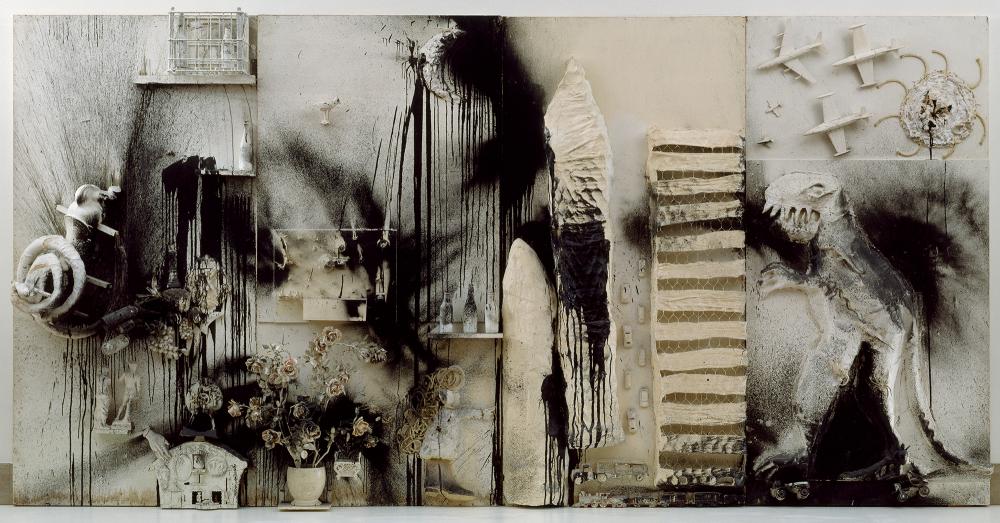

The postwar art scene was dominated by masculinist gestures of power and grandeur. Saint Phalle both resisted those postures and deployed them to great effect. The theme of violence that lurks in the first room is intensified in Saint Phalle’s Tirs series, works made by shooting at arrangements of found objects assembled into vignettes to be assaulted. Element of Tirs Tableau Sunset Strip (Vacuum Cleaner) (1962) is a vacuum cleaner that—isolated from the tableau it was once a part of, with bag deflated and stained in paint splatter—stands as a withered relic, even a memento mori, of household chores. In the larger frieze-like works, the aftermath of the shootings manifest as a field of explosive color, enlivening the monochromatic palette and shifting the tenor of the pieces. Phallic representations of skyscrapers are attacked by monsters on skates in two multi-paneled friezes of 1962, Pirodactyl over New York and Gorgo in New York. The monster Gorgo, who is sometimes interpreted as allegorizing the pervasive postwar threat of atomic warfare, is a mother who terrorizes humans in search of her missing offspring. Black paint explodes and dribbles down over the city, expressing a kind of toxic grief. In Red Dragon (1964), Saint Phalle constructs a monster of plaster, mesh, string, and hair who withstands an attack of plastic GI Joe-like figures; it is both ferocious and, with its protruding eggs, overtly female.

Saint Phalle went on to explore typologies of the female figure even more intensely in her Nana sculptures, which fill the exhibition’s third room. In French, nana is a slang term for girl, but Saint Phalle might have also appreciated that in English, nana is a term for grandmother, thus conveying a multigenerational idea of womanhood. These larger-than-life forms exaggerate the breasts and buttocks of the female form with exuberant color; occasionally toting handbags or sporting heels, they embody power and sometimes joy.

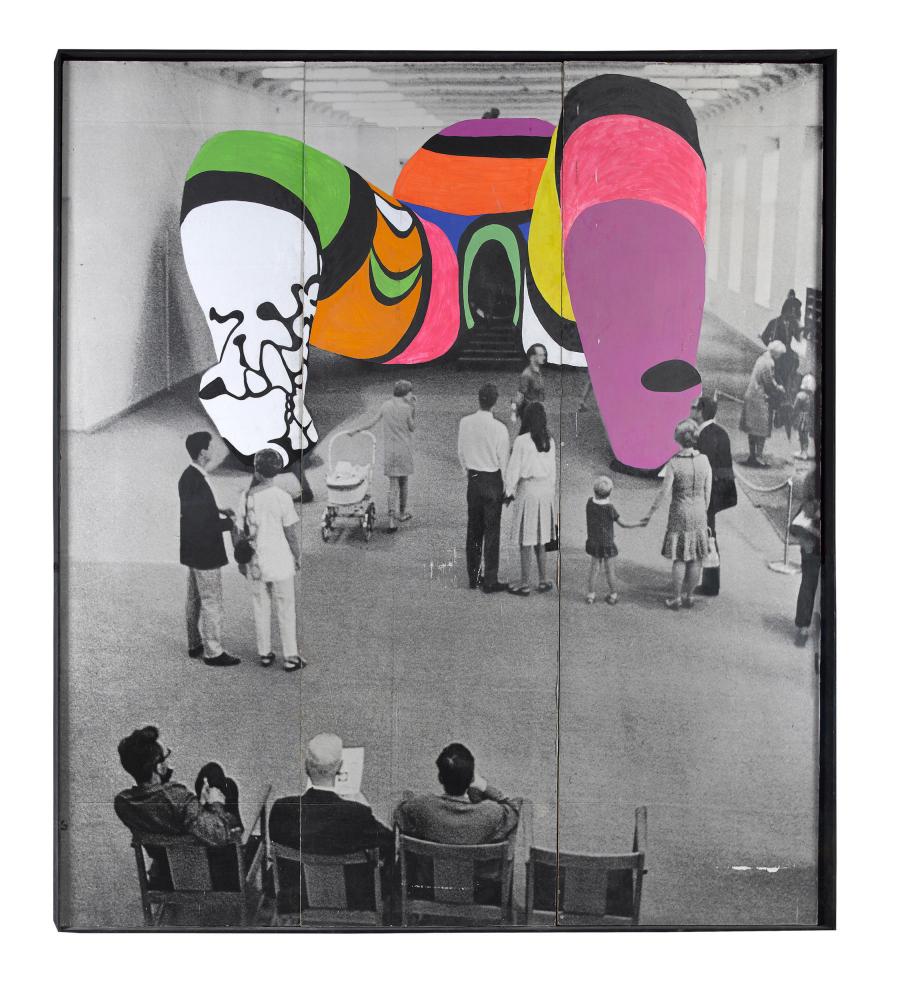

In the last room of the exhibition, a reclining nana, Model for Hon (1966), greets viewers exactly as Saint Phalle’s enormous prone Hon installation at the Moderna Museum in Stockholm would have during the summer of 1966. Saint Phalle referred to Hon as a cathedral, reveling in the thousands of visitors who were transformed after entering the figure through the dark cavern between the legs—female form as sacred sanctuary. Occupying an entire wall, an overpainted photograph of Hon merges the black and white language of documentary with Hon’s dayglo colors to give a sense of the sculpture’s architectural scale and allure. Now inhabitable, the building-sized Hon included a gallery with fake paintings, a planetarium, and a milk bar in one breast. Saint Phalle’s nanas grew to be monumental, but never monolithic.

A display of ephemera from the Menil Collection’s archives adds context to the artworks. The spread includes articles from Vogue and Life magazine which delighted in Saint Phalle’s chic persona. The curators made an important strategic decision not to introduce Saint Phalle herself until this final room. Watching the footage of the shootings and hearing interviews with Saint Phalle (from a film by François de Menil), we can better understand her determination as an artist of action, in defiance of the glamourous fashion spreads in which she would always be an object. Also on display are Saint Phalle’s artist books that the de Menils collected, alongside preparatory drawings and archival photographs.

Relentlessly experimental, the strength of Saint Phalle’s work lies in its vulnerability and versatility. We see Saint Phalle constantly enacting an alternative way to relate to a world in which women’s agency itself was—and still is—perceived as destabilizing. Niki de Saint Phalle in the 1960s shows us that there is pleasure in the fight to be, and see, differently.

Sandra Zalman is the author of Consuming Surrealism in American Culture: Dissident Modernism and the co-editor of Modern in the Making: MoMA and the Modern Experiment 1929-1949. She is Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Houston and is currently working on a book about museums of modern art at midcentury.