“Roberto was brown and his people lived next door so of course I went over on weekends.” So opens Bryan Washington’s Lot, his debut collection of stories published in Spring 2019. The book follows a family who lives in Houston’s East End, but the central narrative is interspersed with stories of other lives, collapsing events that stretch over miles and years into one sweeping and immediate glimpse. The recurring narrator, whose name remains concealed until the last pages, has a Black mother and Latino father and is the youngest of three who help run the family restaurant that is “always short on rent, always out of everything on the menu.” His sister Jan moves out of the house at the earliest opportunity. He muses with his brother Javi about what his father’s mistress looks like. On the weekends he accompanies his mother on her weekly market trips, which involve taking the earliest cross-town bus and agreeing to keep her dancing to the Mariachi music a secret from his family.

Lot’s stories are as much about Houston as a place as they are about family. The city’s scrappy entrepreneurial spirit comes through in Washington’s details. The narrator's father "pitched Ma the restaurant like a pimp, like a hustler" and soon the couple "found a shotgun off the freeway [and] polished it up." Washington also weaves elements of Houston's food culture and the South's history of sharecropping, with multiple passages that reference food preparation and the family’s older generations. Over time the land under the restaurant appreciates, buoyed by East Houston's rising real estate prices in the last decade, and becomes important to the book’s plot.

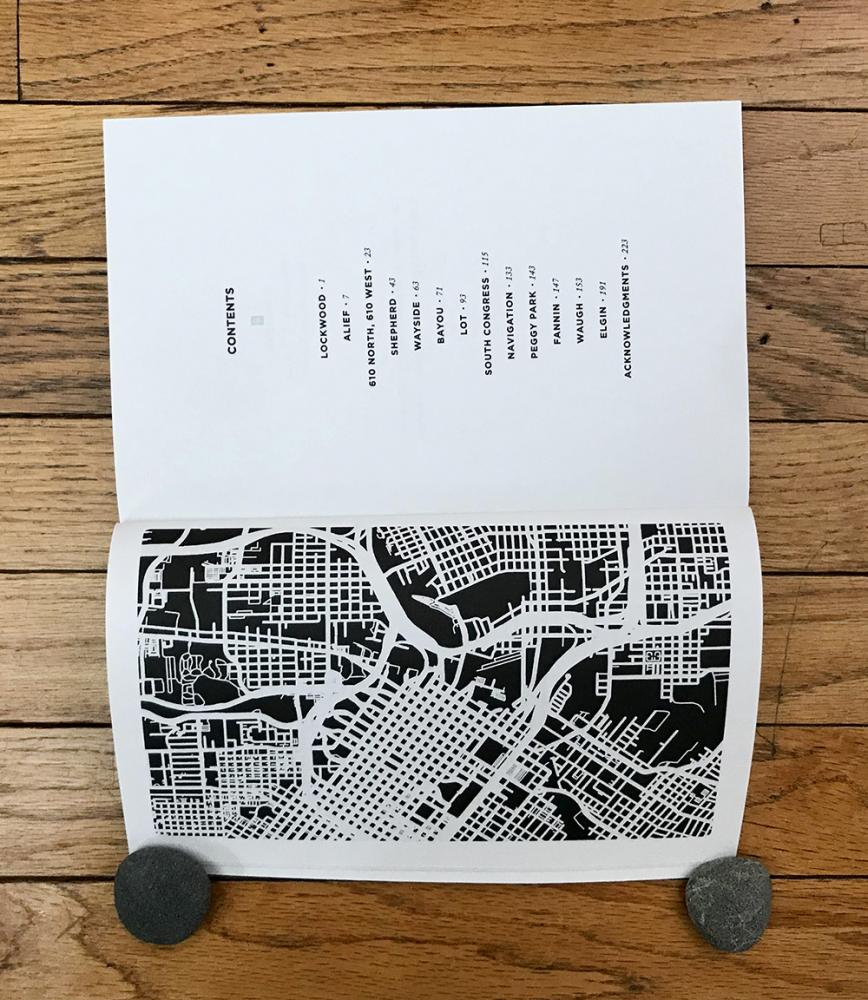

To the Houstonian, this book feels like it is for us. Opposite Lot’s table of contents is a landscape format figure-ground map of the city that shows the downtown confluence of Interstates 10, 45, and 69. The chapters are named after streets and neighborhoods that only a local would recognize: Lockwood, Alief, Shepherd, Wayside, South Congress, Navigation, Fannin, Waugh, Elgin. Lot personalizes a place often known to outsiders only for its oil extraction and dignifies a sprawling city that receives little mention in the contemporary literary world.

I moved to Houston in my mid-twenties and rented a ground floor apartment with a window unit on Richmond Ave. It was August, my first time living alone, and also my first time needing air conditioning. The city's swampy overgrowth and perennially flooded gutters defied my expectations of an arid Texas filled with cowboy pastures and ranch land. I spent the first week biking around and falling into the city's unforgiving potholes; sweat stung my eyes, causing me to lose my grip on my handlebars. I slowly got to know Montrose, East Downtown, the Heights, and Chinatown, memorizing the streets with bridges that crossed over Highway 59/69. I adored these crossings on my rides home after late nights in the architecture studio, times when the sleepy Museum District burst into an expansive stretch of light and speed. Washington's words recontextualized this landscape that had become my new home, revealing depths and tensions that were invisible to me. I found myself delighted when recognizing the Chevron on Richmond and St Thomas—a landmark that appears in one of the stories—and ashamed when I realized my proximity and obliviousness to Houston's worlds beyond my race-and-class-determined circuits.

It is tempting to see this collection as an equalizing force, one that gathers Houstonians and our multifarious experiences in a rare moment of communal pride, but that approach doesn’t really work. In chapters that alternate with the central plot, we see different lives: An upwardly mobile family moves into River Oaks and takes in a cousin from Kingston, five boys living in a complex on Montrose with rusted pipes evict their housemate when word gets out that he is HIV positive, and a teenager from Guatemala stays with his aunt and roofs houses until a drug dealer takes him on as his driver. Lot points out important differences. It confronts, head-on, the disparities between the experiences of those who are gay, poor, and Black, and those of gentrifying white people, the “Peter Parker types” renting East Downtown condos in an attempt to live in “the real Houston.” In one story, the central narrator sleeps with a white boy who works at a local non-profit, after which he agrees to teach him Spanish for fifty dollars an hour. Without didactic rhetoric, Lot involves us in an intimate grappling with race, showing us how it conditions how we talk to waiters, make friends, have sex, and grow up.

Though Lot is a year old, it remains powerfully prescient in today’s national reckoning with what it means to live and die in America. One character reflects that “Ma told her to wait it out. That’s just what America did to you. They’d learn to adjust, she’d crack the code, but what she had to do was believe in it.” After the murder of George Floyd, a Black Houstonian, communities across the country are marching together. They are protesting against the reality that our chances of “cracking the code” are inextricable from how we look, that the rules which determine who struggles to survive and who has the luxury to look away are defined by factors other than hard work and self-determination. While these messages are not new, the level of attention around these issues seems to indicate that society today is more interested in addressing privilege, ethics, and accountability more than it ever has been. Our COVID-19 economy has made visible who is eligible for unemployment, who receives a government check, and who has to choose between risking exposure at work or losing their job. In this moment it bears noting that Ma’s advice—wait it out, believe in it—only makes the powerless stay that way. Patience, self-reliance, and dedication to the American dream, rather than active lifting out of poverty, perpetuates it, for some. Lot sustains this contemplation as it conjures vivid imagery of a male adolescence structured by Houston’s endless roads, sticky atmosphere, and immigrant enclaves. Washington brings us up close, entangling us with his subjects’ affection, violence, and wonder. He turns our attention to what are common experiences for many in America.

The stories in Lot are powerful due to Washington’s abilities as a writer but also because they come from his personal commitment to depicting what it feels like to grow up in Houston today. In other writing he gives readers a sense of how one figures out where they belong and find themselves in this cosmopolitan southern city. In his 2019 essay "One Word: Boy" in The Paris Review, Washington meditates on the universality of boyhood and youth while explaining the wide range of subtexts that comes with the word’s utterance: "When my aunt calls me boy, in a sprawling patois, it’s not the same boy I’ve heard on fuck knows how many crowded street corners, at whatever ungodly hour." Washington's writing is made specific and accessible through using neighborhood names and ubiquitous chain establishments. In his New Yorker article about the public viewing of George Floyd's body at the Fountain of Praise Church in Fondren Gardens, he describes parking "at a Home Depot ten minutes away by foot" before waiting in line to pass by the casket. He captures what Houston feels like right now, from Chinatown to Kashmere Gardens and everywhere in between. Washington’s first novel Memorial comes out in October.

Earlier this week, Rice University announced that Bryan Washington has been appointed to the newly-created two-year position of Scholar in Residence for Racial Justice. Washington will also hold the title of George Guion Williams Writer in Residence and will offer courses in Creative Writing, including a course named “Writing Black Lives,” during his tenure as Scholar in Residence. According to the internal announcement from Rice University, he will work with the Center for African and African American Studies and with the Task Force on Slavery, Segregation and Racial Injustice on campus events on racial justice. Washington was previously a visiting lecturer in Creative Writing in the Rice University English Department, where he taught an introductory fiction writing course last Spring.

Tiffany Xu is a graduate from Rice Architecture. Her recent work explores depiction in film and architecture.