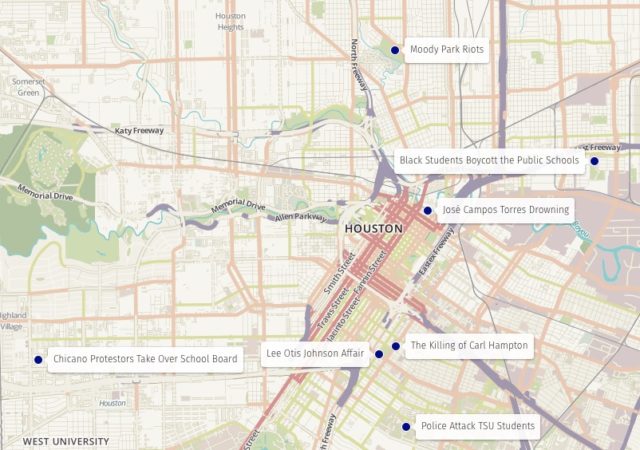

This article originally appeared in Cite 82 (pdf) and is now accompanied by a digital map.

Houston has a long history of segregation and racial violence. From the lynchings of George White in 1859 and Robert Powell in 1928, to the hanging of black soldiers who rebelled at Camp Logan in 1919, to the rise of the local Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, racist actions have periodically threatened to tear the city apart.

The political struggles of the 1960s and ’70s changed the city. In the 1998 movie The Strange Demise of Jim Crow, historians explain how the end of segregation in Houston came relatively quickly and, due to a media blackout, without fanfare.

Highlighted in this piece are important milestones that dispel an oft-repeated myth that Houston’s quiet desegregation prevented riots, rebellions, or open conflict; moments of community indignation (anything but polite and restrained) that lead to concrete action on the road to political power for people of color in the city. Many events have been left off this list — the University of Houston riot in 1969, for example — but the sites selected can serve as initial entries into an often ignored history.

1965, Black Students Boycott the Public Schools

Wheatley High School, 4900 Market Street

To protest the slow pace of integration in the public schools, despite its being court ordered in 1960 and again in 1962, 85 percent of the students boycotted five black high schools in Houston in 1965. Rev. William Lawson, minister of Wheeler Avenue Baptist Church, organized the students to assemble at the South Central YMCA. In his words, “We had this bunch of kids starting the march, but the good news was the HISD headquarters was downtown on Capitol, so we went down Dowling Street, and while we went down, there were people who came out of the houses and out of the businesses and joined us. So we ended up with at least hundreds if not thousands of people.” The boycott and march were instrumental in making the superintendent of HISD push desegregation along faster.

Protests on April 6, 1967 in front of the Harris County Courthouse against the police crackdown on the TSU campus that culminated the next month. Source: Houston Metropolitan Research Center

Protests on April 6, 1967 in front of the Harris County Courthouse against the police crackdown on the TSU campus that culminated the next month. Source: Houston Metropolitan Research Center

1967, Police Attack Texas Southern University (TSU) Students

TSU Campus

In the late sixties, TSU student activists began organizing in new ways, their radicalization influenced by the Black Power movement and largely pushed along by a group of student activists identified as Friends of the Southern Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The students were protesting police brutality and seeking to shut down the portion of Wheeler Avenue that bisected the campus. A series of rallies in early 1967 (including one led by Stokely Carmichael) culminated in a police siege of TSU as the city sought to quell the increasing anger and organized protest on campus. On May 16, 1967, police invaded the campus. Students fought back as officers axed their way into dorm rooms and took everyone outside, beating many of them brutally. Police fired thousands of rounds of ammunition. By the end of the day, they had arrested 480 students and one officer was dead. (Time magazine said it was probably from a stray police bullet.)

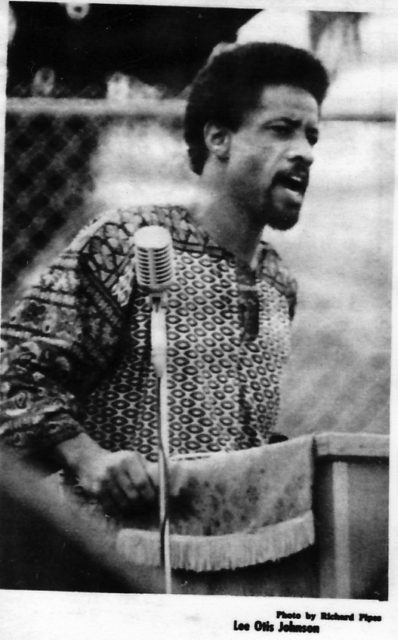

1968, Lee Otis Johnson Affair

Emancipation Park, 3018 Dowling Street

Lee Otis Johnson was one of the student leaders at TSU during the run-up to the May 1967 police action and in the years following. Arrested in 1967 and later expelled from TSU, he became the face of the militant civil rights movement in Houston, appearing on television with his brash, no-holds-barred attitude. On April 14, 1968, at a memorial service for slain leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at Emancipation Park, Mayor Louie Welch attempted to address the crowd; the audience booed, and Johnson stood up to speak out forcefully against the mayor. Three days later he was arrested for trumped-up charges of passing a small amount of marijuana to an undercover policeman. In August 1968, Johnson was convicted of possession of drugs. Harris County DA Carol Vance, who personally tried the case, sought a sentence of 20 years, but the all-white jury went further, giving Johnson 30 years. Five years later, following protests and appeals by his supporters and lawyers, Johnson was released by a federal judge who ruled his Houston trial unfair. Johnson became a symbol of radical activism in Houston, and his arrest a cautionary tale of the city’s crackdown on dissent.

1970, Chicano Protesters Take Over Houston School Board Meeting

Hattie Mae White Administration Building, 3830 Richmond Avenue

The Justice Department filed suit against the Houston Independent School District (HISD), alleging that it continued to segregate its students. In response, HISD instituted a desegregation plan that mixed Mexican-American and African-American students, but left Anglo students largely unaffected. (The League of United Latin American Citizens had previously fought for Latinos to be officially designated as white to prevent their segregation.) To resist this ploy, a number of community groups began to push for Latinos to be recognized as “brown, not white” (chronicled in Guadalupe San Miguel’s 2001 book of the same name). The Mexican American Educational Council organized a huelga (strike) of schools around Houston. The conflict came to a head when the HISD board refused to hear from a group of Chicano parents, students, and activists, including members of MAYO (Mexican-American Youth Organization). In protest, the group took over the meeting, grabbed the microphones, and stood on tables as they chanted, “Chicano, Chicano, Chicano,” and loudly demanded change. Partially as a result of this action, HISD agreed to the community demands for recognition, and by the end of the year, the boycott had ended.

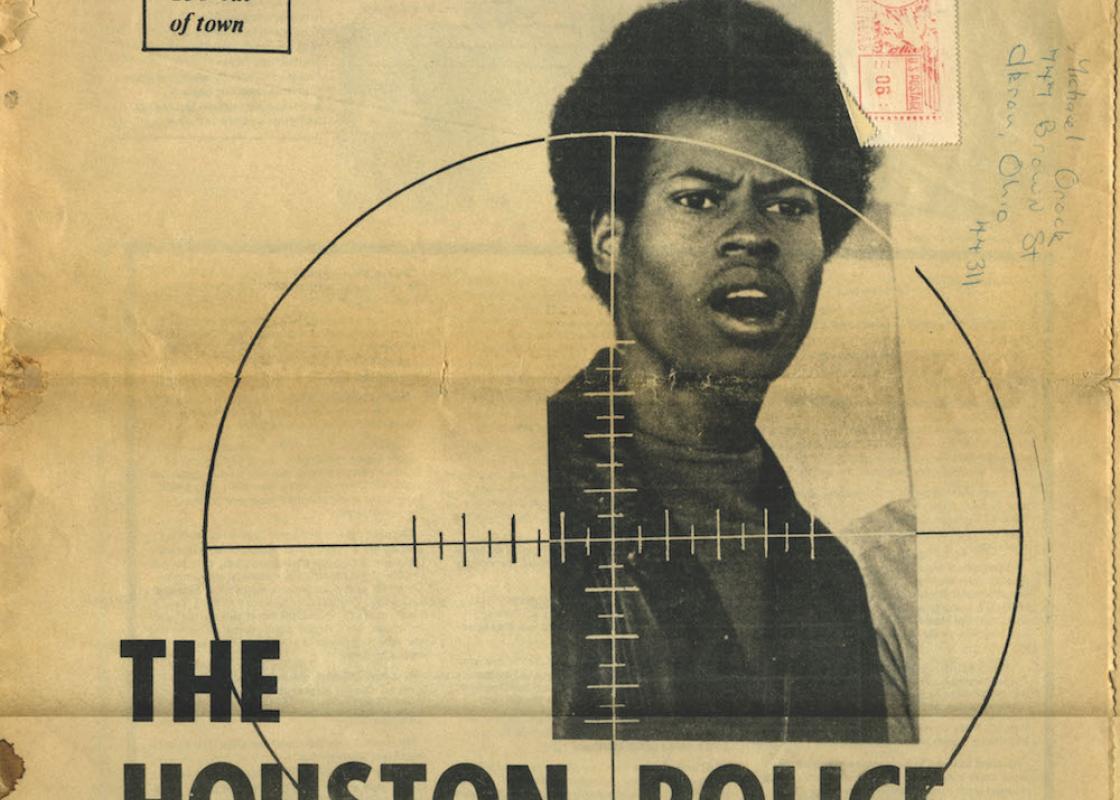

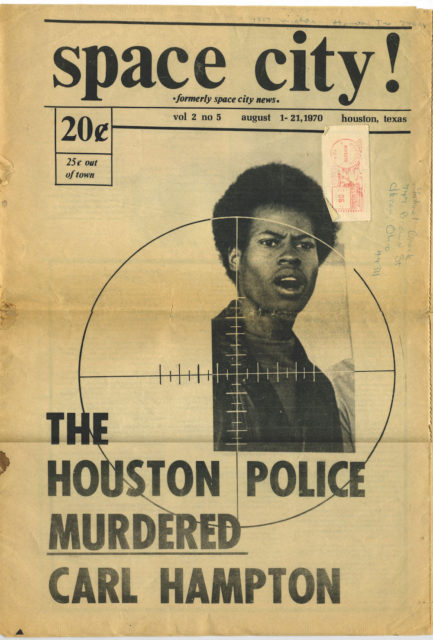

1970, The Killing of Carl Hampton

2800 block of Dowling Street

Toward the end of the 1960s, organizers were radicalizing—in the Chicano community with MAYO and in the black community with the People’s Party II. Carl Hampton was a leader in Houston’s chapter of People’s Party II, modeled along the lines of the Black Panthers. According to Charles Freeman, another organizer active at the time, Hampton had returned to the party headquarters on Dowling Street when he saw a Houston police officer harassing a member selling Panther newspapers. The officer and Hampton (who was carrying a legal, unconcealed weapon) briefly faced off against each other. Hampton and his compatriots then holed up in their headquarters as police gathered. Ten days into the standoff, Hampton spoke to a gathering of community members and student supporters. After this rally, police officers standing on top of nearby St. John’s Baptist Church opened fire on the party activists, wounding four people and killing Hampton. The story of Hampton’s killing has been largely erased from Houston history; in recent years increasing efforts, largely by black community activists, have drawn attention to what happened, making sure that Hampton and his murder are not forgotten.

1977, José Campos Torres Drowning

Buffalo Bayou between Allen’s Landing and the McKee Street Bridge

José “Joe” Campos Torres, a 23-year-old Mexican-American Vietnam vet, was found floating in Buffalo Bayou on May 8, 1977, two days after his arrest by Houston police officers following an alleged bar fight. The officers had arrested the vet, beat him, and then left him at the jail. The jail staff told the officers that Torres needed to go to Ben Taub because of his injuries. Instead they threw Torres into the bayou, where he drowned. Eventually, after community outcry, the officers, including Terry Denson, were brought to justice. The sentence of a year of probation and a fine of $1 each prompted more community anger and a federal civil rights trial, which resulted in a year of prison time for some of the officers.

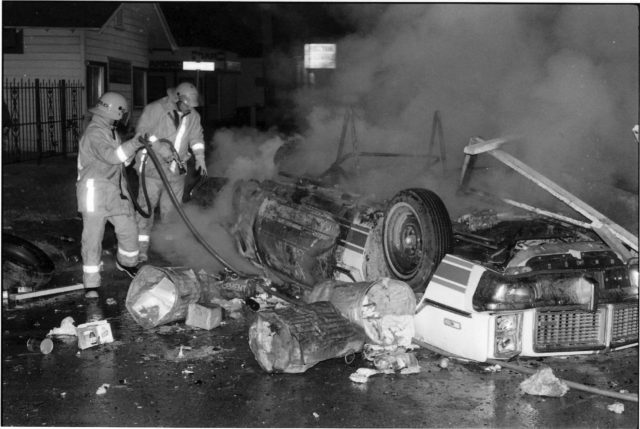

Firefighters attempt to put out the flames from a car overturned. Source: Houston Metropolitan Research Center

Firefighters attempt to put out the flames from a car overturned. Source: Houston Metropolitan Research Center

1978, Moody Park Riots

Irvington Blvd. and Fulton St.

A year after Torres’s death, a commemorative event in Moody Park led to violence as the community fought back when police officers tried to make an arrest at the park. All of the anger, fear, and rage of the past year boiled up, and the park became the epicenter of rioting that spread around a 10-block area in the Mexican-American Northside. Organizer Travis Morales, who was present at the park, recalls that young people were chanting, “Joe Torres dead, cops go free, that’s what the rich call democracy.” In the end, 15 people were injured, cars and businesses were burned, and the relationship between police and communities in Houston was forever altered. The riots sparked a process of reform within the Houston Police Department (HPD), and increased communication between communities of color and the HPD led to large numbers of people of color joining the force.