Driving up from Houston, Nacogdoches emerges from the pines of East Texas. The town rightfully claims the title of “The Oldest Town in Texas”: when Spanish missionaries arrived, it was already Nevantin, the main settlement of the Nacogdoche tribe of Caddo peoples. (The word Texas comes from the Caddo teycha, meaning "friend" or "ally," which the Spanish converted into Tejas.) The land provided a means for survival then, as it does today. As such the town was the perfect place for last month’s East Texas Mass Timber Symposium, hosted by Stephen F. Austin State University and their Arthur Temple College of Forestry and Agriculture, where the main topic was the future of both forests and buildings in Texas.

Mass timber uses laminated pieces of wood to make elements like walls, floors, columns, and beams. This two-day symposium brought together forest industry professionals and architects to share research and construction efforts using the technology. Experts gathered at SFASU’s Ina Brundrett Conservation Education Building in a conference room full of windows to the woods beyond.

Though the first contemporary mass timber buildings were only realized in the 1990s, the technology has quickly become a structural system with considerable promise. Not only does it invite experiential associations of wood to create “warm” interiors, but it also reduces the carbon footprint of construction, as buildings account for 40% of all CO2 emissions, though operational carbon greatly outweighs embodied carbon. Its advantages stack up.

Mass timber is already regulated: the 2021 International Building Code (IBC) includes provisions for mass timber buildings up to eighteen stories tall. (This, of course, requires local authorities to use these latest codes; Houston is still in the process of updating to the 2015 IBC, which allows mass timber buildings up to eighty-five feet in height.) Expanding out from the wider market for wood building products, an industry has sprung up to support mass timber. For assistance, you can download the Mass Timber Design Manual, published by WoodWorks and Think Wood, and the U.S. Mass Timber Construction Manual, produced by WoodWorks. There are mass timber institutes, laboratories, consultants, fabricators, networks, and conferences. Sidewalk Labs, an urban innovation company owned by Alphabet (Google), even wants in. TimberCon, a large online conference organized by The Architect’s Newspaper, was held on the same Thursday as this symposium.

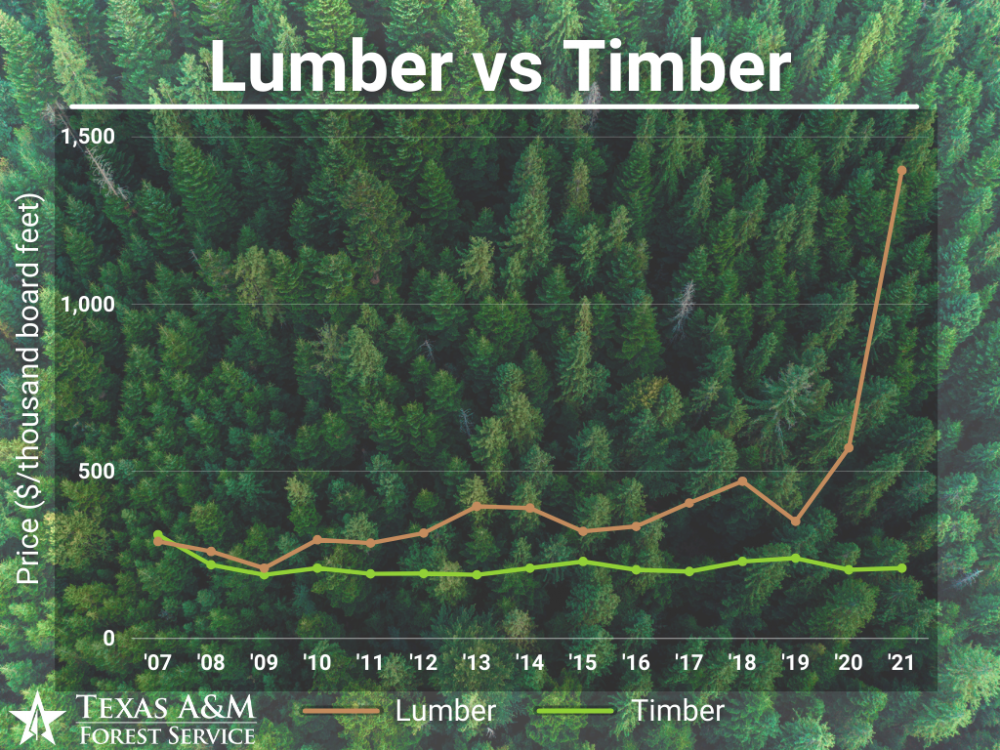

In Nacogdoches, Dr. Aaron Stottlemyer, a Forest Resource Analyst with the Texas A&M Forest Service, made the case for cross-laminated timber (CLT) made with Southern yellow pine grown in Texas. The state has 13.9 million acres of timberland, with 11.9 million of those acres in East Texas. 90% of timberland is privately held and lately the grow ratio has been larger than 1, meaning more wood is grown than harvested. This sets the stage for an upcoming “glut of timber” in which landowners will be looking to turn a profit in a market flooded with material. New wood products are needed, hence the interest in mass timber. Stottlemyer reviewed the economics of Texas forests and explained the surge in lumber prices during the pandemic, a combination of shuttered sawmills and increased demand, versus the consistent price of timber, in addition to other statistics. By his calculations, East Texas forests grow a building every twenty seconds.

Other presenters delivered practical information for architects. Mark Bartlett, a Regional Director for WoodWorks, went through terminology and best practices, including how to control for vibration and good acoustics. His organization also tallies mass timber projects around the country; as of September there were 267 built, 576 in construction, and 665 in design. The tallest mass timber building currently is a nine-story, 500,000-sf center in Cleveland—at least until a twenty-five-story project (eighteen in mass timber) completes in Milwaukee.

Steve Durham and Darrell Whatley, of Kirksey Architecture in Houston, gave presentations about their experience using mass timber for two projects in Houston, noting the importance of design team coordination. While mass timber can be more expensive than other methods, it’s important to look at cost holistically, as the technology can trim construction timelines, reduce labor costs, and eliminate finishes. If done right, the practice can support good forest management. It’s about simpler design and better value, Durham said.

Dr. Pat Layton, Professor of Forestry and Director of the Wood Utilization + Design Institute at Clemson, shared her experience as part of the team who realized Snow Family Outdoor Fitness and Wellness Center, designed by Cooper Carry. In addition to her presentation, Layton provided the keynote address that morning, which shared the message of mass timber with a larger audience gathered for the annual meeting of the Texas Forestry Association (TFA), themed under the heading Re-Imagining Wood: The Sky is the Limit. The event, held at the Fredonia Hotel, was also the venue for the debut of a new mass timber construct by James Michael Tate, Assistant Professor of Architecture at Texas A&M University and Director of T8projects.

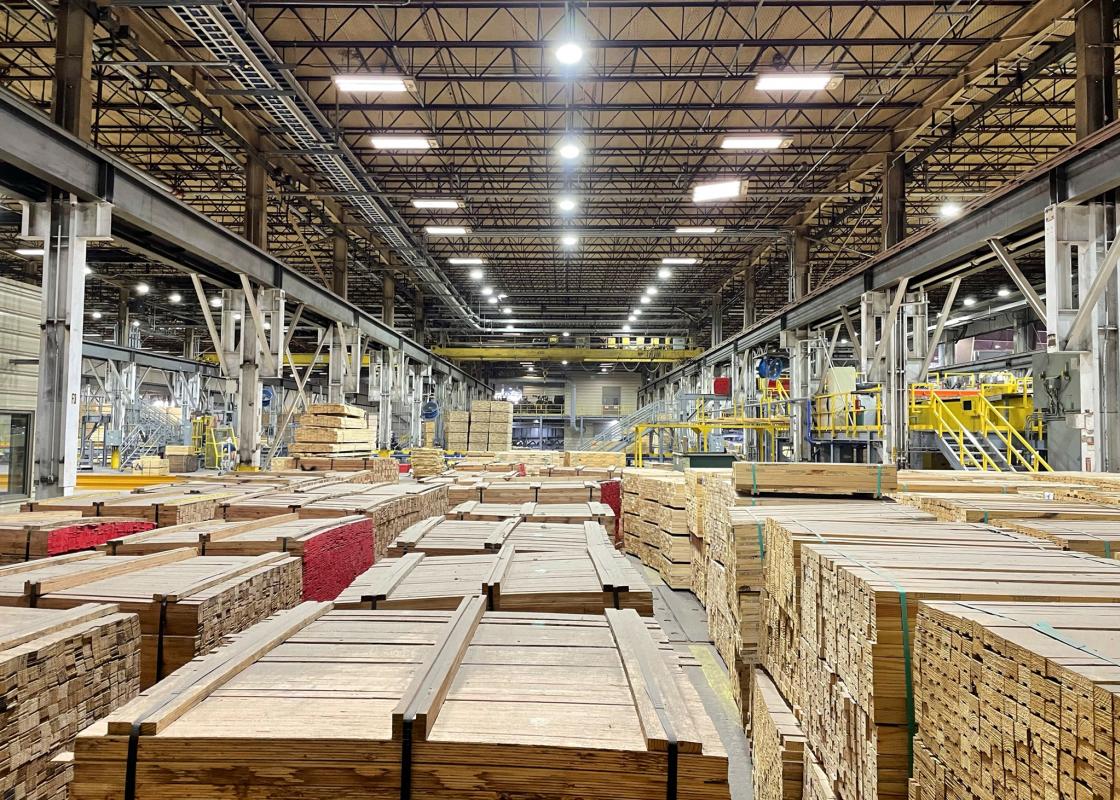

While the presentations were instructive, the highlight of the symposium was two tours held on the first day. In Lufkin, the group visited Angelina Forest Products (AFP) and Sterling. AFP, a sawmill, began operations in October 2019. The operation regularly processes over a hundred log trucks per day in two eight-hour shifts; production exceeds one million board feet per day. Here, sweet-smelling pine logs are unloaded, analyzed for efficient cuts based on trunk shape and market demand, cut, planed, kiln dried for thirty hours, and stacked to await delivery to local stores. The sequence is impressive due to its speed and automation; rotating saw paths even account for curving grains, producing warped green boards that flatten out during drying. Excess wood fiber is used for other products, so almost none of the tree is wasted. The tour left guests impressed, all in agreement that AFP was a “beautiful mill.” It’s also a good investment: the facility cost about $100 million to start up and was sold last month for $300 million.

Sterling’s CLT factory is nearby. Their mats are available in 8’ widths up to 18’ long and in three-, five-, or seven-ply thicknesses. In a vast warehouse, their machinery processes 2x8s, organizes and sequences layers, distributes glue, presses stacks on three sides at ninety PSI for twenty-five minutes, and trims panels; their cut edges are sealed by hand prior to use. Three presses, custom designed in Germany by Minda, slide laterally on rails, taking turns accepting and compressing piles of CLT. The factory makes one panel per minute. Cutting or routing isn’t available onsite, as the panels aren’t intended as building products but as site access mats, though there’s no difference in manufacturing. Sterling’s TerraLam® product is aimed at the energy sector: when working on pipelines or power lines, these mats are laid down first for vehicular use. They’re in high demand. Together with their plant in Chicago, Sterling’s output has been greater than all other outputs in North American and Europe combined. But that wasn’t the case during our visit: given the high price of lumber, the plant has been closed for months.

After attending the informative East Texas Mass Timber Symposium, it’s clear that architects have both the design and technical ability to utilize mass timber in creative and appropriate schemes. It’s also clear that the forest industry is actively seeking new timber products which would utilize their lumber. What’s missing is the middle step of widespread demand for this system, which would incentivize increased CLT production. Currently, Texas CLT produces panels in Magnolia, Arkansas, and Structurlam recently opened their plant in Conway, Arkansas, in part to supply mass timber for Walmart offices; the latter facility will also supply panels for the new wing of Hanszen College at Rice.

While the embodied carbon of building construction is small compared to operational carbon—and while it isn’t possible to realize every new building in timber without risking deforestation—the technology could aid in significant reductions. In replacing steel and concrete, it could also help ease supply chain issues that are painfully common today. Aside from not producing new buildings at all, this might be the next best thing. The architecture and the apparatus stand ready for mass timber to succeed; all that’s missing is the ambition.

Additional mass timber coverage is forthcoming in Cite 103.

Jack Murphy is Editor of Cite.