In this interview conducted via Zoom in October 2020, Cynthia Phifer Kracauer speaks with Kathryn O’Rourke about her productive time in the office of Johnson/Burgee Architects and her role in the design of Transco Tower. The conversation showcases the high level of quality provided in the office’s work and the social atmosphere of the firm. They also discuss current events, including how the pandemic has affected the successes of women in the architectural profession. The interview offers a welcome glimpse into the working life of an architect at the start of her career.

For better or worse, Philip Johnson was one of the most important American architects of the 20th century. He was the first recipient of the Pritzker Prize, winning it in 1979, and remains only one of five American laureates to date. But lately, in the wake of America’s reckonings surrounding racial equity, Johnson’s legacy has come under siege, given his active participation in Nazism during the 1930s. Under pressure, the Harvard GSD announced it would rename the Johnson thesis house last year. A campaign is underway to remove Johnson’s name from the lead curatorial role for architecture at MoMA, currently held by Martino Stierli, and the architecture gallery at the museum. The signage bearing Johnson’s name remains covered during the current show Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America. As of March, research by MoMA into this history is “ongoing.”

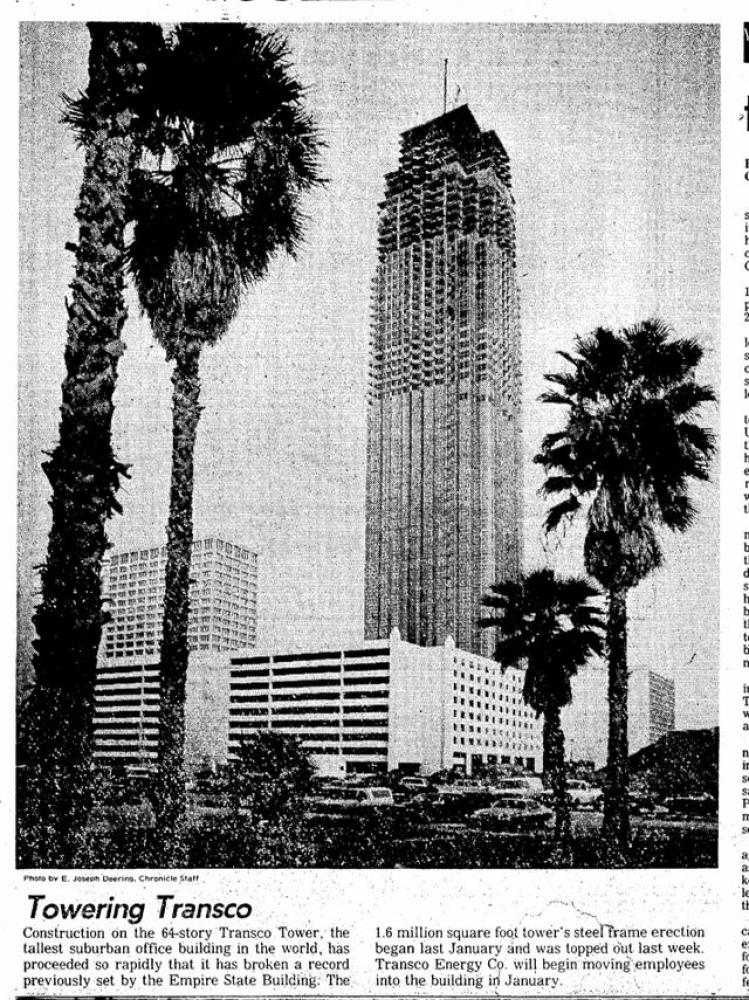

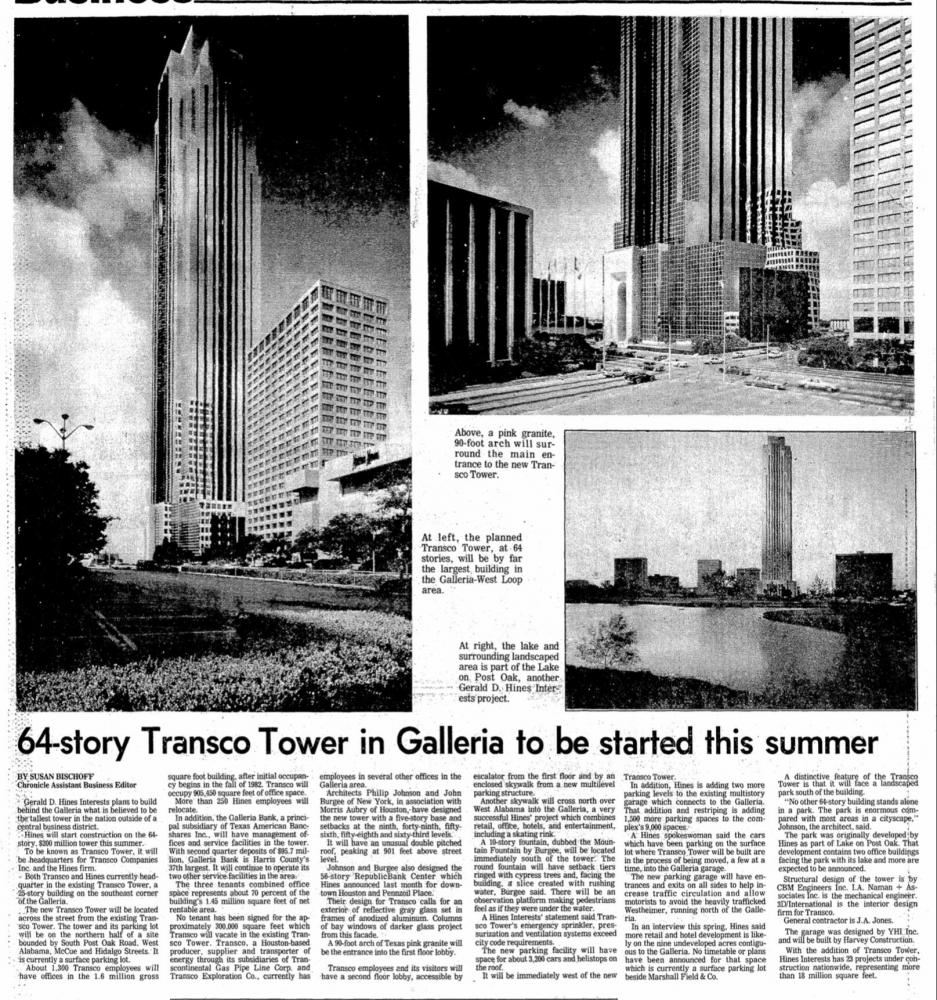

Whether or not Johnson’s actions are grounds for canonical cancellation is up for debate. As it relates to his buildings, the discussion gets more nuanced in Houston, where Johnson was a major architectural operator beginning in the 1950s, when his tastemaking ability anointed Mies van der Rohe as the idol of choice for a generation of local architects. Later, he was catapulted into an even brighter spotlight with his designs that put Houston on the map for American architecture. Buildings like Pennzoil Place (1976) and Republic Bank Center (1983), now TC Energy Center, introduced new shapes and vocabularies into the design of skyscrapers. Johnson’s Transco Tower (1983), now Williams Tower, is topped with a rotating search light, which has given Houstonians a point of nocturnal orientation for decades. The adjacent Gerald D. Hines Waterwall Park is a major destination in the city. Houston’s NOMA chapter even uses Pennzoil Place in its logo, a symbol not of Johnson’s genius but of hometown pride. It’s refreshing that, over time, the particular identity of the architect dims as buildings and spaces become adopted by the city and its citizens. —Jack Murphy

Kathryn O’Rourke: You worked as an architect at Johnson/Burgee in the early 1980s. One of your main projects was the Transco Tower in Houston. Could you tell us a little bit about the office and what it was like to work there?

Cynthia Phifer Kracauer: It was a unique experience. After graduate school, I had been teaching at the University of Virginia. I decided that a life in academia was not why I had gone to architecture school. I wanted to work on big, important buildings. I set my mind to finding a job where I could work on big, important buildings. This was 1979 or 1980. I interviewed at all the big firms in New York City. I made my decision based on the reputation of Johnson Burgee, which was that everybody left at 5:30, as opposed to other firms where people worked eighty-hour weeks. After the independence of having an academic career where I came and went for studio, I really wanted to enter that kind of rigorous environment with some sense of limitations, you know? I called up all my higher-level friends—people and faculty members who I knew had lunch with Philip Johnson regularly—and asked them to speak on my behalf, which they did.

I started at Johnson/Burgee in May 1980. At that time, a number of projects for Gerald Hines had already been done. All of the lower-rise Galleria projects were basically complete, and Republic Bank Center and Pennzoil Place were already finished. It had kind of remade Houston and remains an incredibly beautiful building. There were stupendous projects in progress when I joined: Transco Tower and PPG Place were on the boards, and the AT&T building in New York was in construction documents. It was this period of tremendous experimentation about what a tall building could be. PPG Place was a bit further along in terms of design and documentation, so we learned a lot from that project when working on Transco.

The office was on the 34th and 35th floors of the Seagram Building, with Mr. Johnson and Mr. Burgee—we always referred to them this way—on the upper floor. All the art on the 35th floor was just amazing. There was a metal spiral stair that connected to the 34th floor. We kind of thought of ourselves as the galley slaves. While we didn’t have the art or the Barcelona chairs, we had the same Seagram Building view and experience.

The office’s design process was interesting. It was a different take on designing than I had experienced in other offices. Basically, Mr. Johnson would give you verbal instructions, like “make it look like this,” as opposed to drawn instructions. I was more used to someone sketching something and then interpreting those squiggles, but this required a little more knowledge of history. You had to have a pretty thorough background in architectural history to keep up, and also a good sense of his playfulness. He was frequently ironic in both speech and in his work, of course. It was very important to be open to that. You couldn't be too serious because some of the stuff was really downright funny. Some of those buildings in Boston were very funny. One of the buildings in San Francisco—laugh out loud. While you might not take the design seriously, you took the work very seriously, and you took pleasing Mr. Johnson very seriously.

Transco Tower has this stepped massing of a podium, which is about six stories tall, and then it rises up about sixty stories or so, and then it steps again, with a pyramidal structure on the top. When we were working on the top, I was in Mr. Johnson's office, and we were looking out the window towards the East River. He said, “See the Beekman Hotel?” and I'm like, “Which one of those is the Beekman Tower?” I had lived in New York for all of about six weeks at that point. Beekman Tower is a very nice Art Deco building finished in the late 1920s. Suddenly I saw the stepped massing for Transco Tower. That's where that came from—right out the window. This initiated many iterative studies for how to put make this top work and integrate garage doors for the automated window washing equipment.

Did he think about the light that goes around on the top?

Definitely. There were also a lot of radio-frequency antennas, as we weren't quite in the cellular telephone era yet. I remember I knew someone had this huge and heavy phone that they put in their car with an antenna. It was sort of like the Get Smart shoe phone. So there was technology like this on the top of Transco that we had to deal with.

There was so much singularity about Transco. You had the Galleria and all those other low buildings, and then this extraordinary thing, almost like an obelisk or campanile, that rises above this podium landscape.

The project also has a 600-car parking garage, which I worked on. Trying to make the precast concrete parking garage a kindred spirit to the glassy, prismatic expression of the tower was a challenge. It resulted in these precast triangular projections. At one point I got to visit this remote precasting yard in San Antonio. It was really interesting and amazing to see the parking garage pre-assembly and to see these huge pieces of precast concrete that were basically the decoration for the parking garage. I had to mark the ones that I thought were good enough to use, so each one of those triangular projections that was selected has a big “X” on the back in a gigantic felt pen. I haven't been back, so I don't know whether the marks are still there.

Perhaps the most amazing thing was that people like John Manley, who had been there since the Mies days when they did the Seagram Building, who still worked in the office. People like John had an encyclopedic knowledge of almost anything that you would want to know as you were detailing a sixty-five-story office building. The ink on linen drawings of the Seagram Building were in the flat files on the 35th floor, and we just had crappy mylars on the 34th floor. When you went up to handle the original drawings, there was this kind of sacramental aspect to it, with the linen and the ink. Then you realize that John Manley probably drew half of those drawings, and he was just sitting right there in the front. He was wonderful.

History was there with you in the office, even as you continued doing innovative work.

master-pnp-highsm-13400-13416u.jpg

Absolutely. And we knew how necessary it was to know the wider history. I think that was one of the most special aspects of working for Johnson: this higher level of expectation that you would know a lot of architectural history—I mean, you really needed to know. It was a wonderful moment. Obviously as you go through architectural history there are periods when history is denied. People might say “architecture is new. It has no history. We're starting over again.” That was the whole message of modernism, of the International Style. There was a sense of being beyond history. And then in the 1980s there was a recognition that knowledge of history facilitated the expression of meaning in architecture.

Did Johnson talk about the International Style in the 1980s? Was that topic in the office?

Not that I heard. When I was there, it was the period of historic exploration, but Johnson always kept the language of the International Style; that was always part of his toolkit. What he was experimenting with in many ways was the language of other styles, decorative and otherwise. Although when you look at the sweep of his practice there was always an interest in the expressive element, an element that would be a little more prevalent and a little less abstract, but still abstract, nonetheless. In some ways his work was like that of Edward Durrell Stone or even Minoru Yamasaki during the 1960s and 1970s. There was a request, sometimes from clients, for architecture to take up an interest in some referential expression. Of course, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown made that much more explicit by writing and talking about it. They brought this interest into the public consciousness.

I want to shift back to Houston and hear what you thought of the city. What was it like to be there as someone who was not from Texas?

Oh, I was so not from Texas! This was absolutely clear to me every minute that I was in Texas. Locally, we worked with S.I. Morris, who had just formed Morris/Aubry Architects. All these Texas guys were really nice. It was a very interesting experience to be a woman project architect here at that time. Eventually I was pregnant, which really sent them into paroxysms of male protective behavior.

master-pnp-highsm-16800-16800u.jpg

I ate a lot of great Tex Mex here, and there was a Southern courtliness that I had not really experienced before. Texas has its own sort of culture and civilization in the broad context of the United States. Texas is not California—Texas is Texas. And Houston seemed very Texan to me, including the accent.

There was also a sense of state’s vastness. I grew up in California, which is also pretty vast. Both are these gigantic states that, at their start, operated as their own republics. In that sense, they share a similarity in that they both have strong state identities. Maybe all states do, but I hadn't felt it elsewhere. I had lived in Charlottesville, Virginia, which has its own identity that's sort of Jeffersonian. And when you live in New York City, you don't really identify with the state of New York.

How did Houston strike you urbanistically? What about its architectural culture?

It was booming! It was clearly inventing itself as a city. Houston is a city that doesn’t have a strong geographic definition. Typologically, it isn’t an island or a basin surrounded by mountains or next to a river; it was this vast plane of anything. The few live oaks sprinkled here and there gave it a slightly swampy feeling, but it was more about the sense of this vast plane. Subsequently, going to Shanghai reminded me of Houston. Shanghai also has multiple separate centers of intense development separated by flatness.

Houston is flat, swampy, and fast, for sure. But what about its multicentered-ness? Was there a consciousness in the office that your efforts were part of creating a new center? Or as participating in this self-invention?

master-pnp-highsm-12000-12072u.jpg

Oh, absolutely. I think that came mostly through multiple commissions from Gerald Hines. Gerald Hines definitely had a vision. Johnson was very good at turning people's visions into architecture. And in that sense, he was a great service architect, in terms of the service provided to the client. There are different types of architects. There are architects that are artists, starchitects, or whatever you want to call them, where the needs of the client are an excuse for the architecture, as opposed to there being rendered a service that vivifies the vision of the client. That was something that was very useful to learn and see in action, that is, the extent to which Johnson was really a very service-oriented professional.

Hines was great. He was a businessman, and obviously he had a vision for Houston. At this point he was still mostly in Houston; he hadn't worked in New York, but you could tell that he was going to get here and do big things. The Hines team was wonderful. They were all top-notch development professionals. They were excellent managers of the development process, very efficient, and that made us better at our jobs. Those Houston people came to New York subsequently.

It must be thrilling to have been in the middle of one of the most important developer-architect collaborations of the 20th century.

Yes. I never had another experience like this one; it remained singular even though I later did a lot of big work. I ended up being the managing principal at a 200-person architecture office. I did a lot of work in New York City, but the quality of those interactions was never matched.

While you were working, did you have a sense of exactly what Hines’s vision was? Not just for one project, but for the whole city?

I can't honestly say that I did. I had such limited interactions with Hines himself. That was really something that didn’t happen with the little draftspeople like myself, the magic fingers down on the 34th floor. But it was clear that he did have a vision. You could see in the sequence of projects, as well as the academic projects that he funded. He was really an excellent real estate guy.

Shifting gears a bit, how do you see the profession today, thirty-five years into your career? You were in the office until 1983, right?

Yes. A lot was changing as I was leaving that office. I went into a very different work context, one that was much more commercial. Johnson/Burgee was very commercial, but at a high level of execution. I went to work for a different kind of firm. Also, there was a recession coming; it started in the late 1980s and lasted into the early 1990s. This contraction resulted in a period of time when there was a ratcheting down of architectural exuberance. Practices like Herzog & de Meuron showed up, and the innovation weight shifted to Europe.

I think there are so many factors in our architectural consciousness today. There will always be people with the formal exuberance of Gehry and Zaha. They're countered by the focus and necessity of everyday work. A firm like Kohn Pederson Fox, for example, does so much work overseas that when you see their work in New York—like Hudson Yards—it doesn't feel like New York. I felt that any of the projects that the office did in Houston seemed perfect for Houston. They perhaps wouldn’t have worked in New York because New York is so overburdened with context.

To go back to that idea of context and landscape, one of the things that is so striking about Johnson/Burgee’s work for Hines in Houston is the wonderful diversity of it: there’s a variety of distinctive buildings, yet they were all completed by one client and one architect. Obviously, that’s a testament to the vision and talent involved. Thinking at the scale of landscape and going back to your observations about Houston as a vast plane, do you think Johnson was thinking about building in this context? It’s one that is so generic, yet distinctive and different from New York.

master-pnp-highsm-12700-12766u.jpg

Oh, absolutely. I think he wanted to make a nice series of monuments and achieve variety. Basically, he was making the context of Houston for the future. Although I didn't work on the fountain at Transco Tower because there was a separate fountain team, the landscape of the fountain aimed to create an architectural mountain feature. I think that was a direct response to that sense of limitless flatness.

I think that is one of the most beloved spaces in the city. People love being photographed there with the waterwall. That destination is part of that skyscraper, which is pretty unusual. You mentioned the tower as the campanile of the Galleria—itself lifted from Milan—and then this is a version of the plaza.

Right, exactly. That's such a wonderful thing for a car culture. I grew up in Los Angeles, so the car culture aspect of it was not alien to me. You would park your car in a parking garage and go to this landmark, and the landmark would create its own kind of spatial landscape, or ecosystem, if you will. That seemed like a great way to respond to that context. Republic Bank basically did the same thing too: It created its own interesting context.

Did you feel like Houston was like LA? Or not really?

Houston was very hot. I was in town every other week, so many times when I was here it was unbearable. It was even harder when I was traveling while pregnant. I would drive my air-conditioned car into an air-conditioned parking garage and go into an air-conditioned building and live this air-conditioned life.

LA isn’t like that. LA is much more open air. You don't have underground tunnels. In that sense, Houston is a lot like Minneapolis, but for the opposite reasons. In LA you can go places and leave the air conditioning—or at least when I was there, you could do that. In LA, you parked your car, walked, and you went inside. It’s very hard to be in Los Angeles proper and not be aware of the stupendous natural landscape. There’s the vast basin that goes all the way to the ocean, the Santa Monica Mountains, and the San Fernando Valley.

Currently you serve as the Executive Director for the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation, an organization that promotes the contributions of women in architecture. You mentioned being an architect who was also a woman. Where are we with gender equity in the profession?

The pandemic is a bummer. Many of the gains that women had been working so hard to achieve are being undermined by the pandemic. This includes the homeschooling of children while you're trying to work from home. There’s the misunderstanding of education/childcare that remains—education is for everybody, but childcare is for women. The pandemic and this live-at-work and work-at-home situation conflates all of those things and makes it very difficult to untangle. I know many women whose kids can't go to school, and they have to stay home. The babysitter that was okay for picking the kids up and making snacks after school is not the same babysitter that can help the kids with Zoom school. This ends up disproportionately affecting women. This is an issue for all types of work, not just architecture. It’s going to take a while to overcome this problem.

On the other hand, at the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation, we say that we're trying to change the culture, and I think we have moved the needle within the culture. Everybody is talking about gender and racial equity. It didn't used to be a topic, so I feel very optimistic about that. You can transform business processes to mitigate bias, which is where it all begins when fighting systemic racism and systemic bias. The most useful thing is to work on the processes through which these biases are played out, such as hiring and recruiting practices. We need to do this to fight racism as well as sexism and other types of discrimination. This was one of the wonderful things about Ruth Bader Ginsburg: she had a deep understanding of discriminatory practices and knew how they were related to each other and what we could do to mitigate them. Her passing was a loss for the nation. She's really a founding mother, and I hope she'll be recognized as such.

What is your take on the recent attempts at reckoning with Johnson’s anti-Semitism and fascist sympathies early in his career, specifically the moves by Harvard and the Museum of Modern Art to remove his name from buildings and departments?

That is a very long discussion. There are many people who feel that the sins of Johnson's youth, including his political interests, make him unacceptable to our contemporary cultural sensibilities. However, he was for the entirety of his career an actor in the culture, and subject to all of the criticism that the culture has to offer, both for his own person, and for his buildings. Johnson went out of his way to apologize for his infatuation with Nazism. He quite publicly recanted all of that ideology, and repeatedly, both in writing and on television. I am thinking of the Charlie Rose interviews.

Did politics, past or present, come into office culture when you were at Johnson/Burgee?

A lot of women, and men, too, resented Johnson's position within the culture of architecture. His legendary lunches at "his table" at the Four Seasons Restaurant on the ground floor of the Seagram Building, were fantasized about by anyone who was never included. Yes, it would seem that they might have been all men, and it's possible that Johnson in large part created the notion of the Starchitect, but he did not do that single-handedly; the architectural press was certainly complicit, and they ran hot and cold on Johnson. This is one of the reasons why many ardent feminists revile him. I most certainly did not. My experience there made it possible for me to have a family and to be given responsibility way beyond my years of practice. It gave me a close look at the pinnacle of success at the time.

Cynthia Phifer Kracauer is an architect and currently serves as the Executive Director for the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation (BWAF). She joined the foundation following ten years as the Managing Director of the American Institute of Architects New York Chapter, Center for Architecture. Both an architect and a creative institutional administrator, Cynthia was responsible for the creation of Archtober, the New York City month-long festival of architecture and design.

As one of the early pioneers of co-education in the 1970s, Cynthia graduated from Princeton University, receiving both a B.A. magna cum laude and a Master’s of Architecture. She worked for Philip Johnson in the 1980s and taught at the University of Virginia, New Jersey Institute of Technology, and her alma mater.

Kathryn O’Rourke is an architectural historian and Associate Professor of Art History at Trinity University.