A photograph of John Saunders Chase appears early on in the new book John S. Chase – The Chase Residence, the first dedicated publication about the architect. In this image, Chase is standing proud in his driveway with his two sons John Jr. and Anthony (shoes off) accompanying him. John's stance is mirrored in his reflection in the glass of the front door. The adjacent window also reveals Drucie, his wife, standing in front of their home to take this picture. The couple trades places in the next image, with John now photographing Drucie on the porch of the home he designed for his family. In these opening images, the Chase family welcomes readers into their house as they knew it at the start of their lives together.

Located on a cul-de-sac in Houston’s Third Ward, Chase’s home is a simple yet grand building realized by architect John S. Chase, FAIA (1925-2012). It is perhaps one of the most important works from his distinguished career: Not only was Chase one of the first Black students to graduate from the University of Texas School of Architecture in 1952, but he then made history in 1954 by becoming the first African American architect to be licensed in Texas. Chase was also the first African American member of the Texas Society of Architects and the Houston Chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), joining in 1960, and then the first Black Texan to become a Fellow in 1977. Along with eleven other Black male architects, Chase co-founded the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA) in 1971. His accomplishments became the gateway through which many architects of color entered the profession.

John S. Chase passed away in 2012. In 2018, the Houston Public Library (HPL) hosted a two-part exhibition curated by Danielle Wilson: "Chasing Perfection: The Work and Life of Architect John S. Chase" and "Chasing Perfection: The Legacy of Architect John S. Chase.” The first part of the exhibition then traveled to the University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture at the invitation of Dean Michelle Addington. It was here that architect and author David Heymann encountered this material and the idea for John S. Chase – The Chase Residence emerged. In many respects, Heymann is a good fit as a native Houstonian, an architect of houses, and a close reader of and writer about architecture (he is also a past Cite contributor).

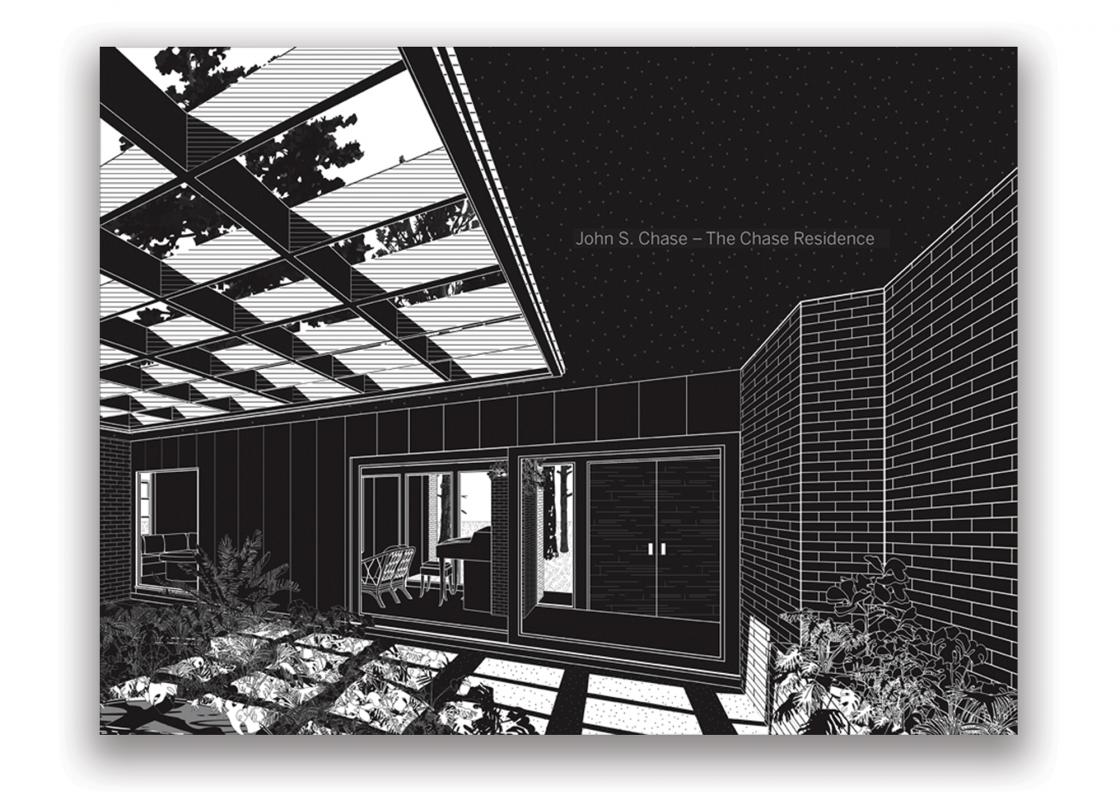

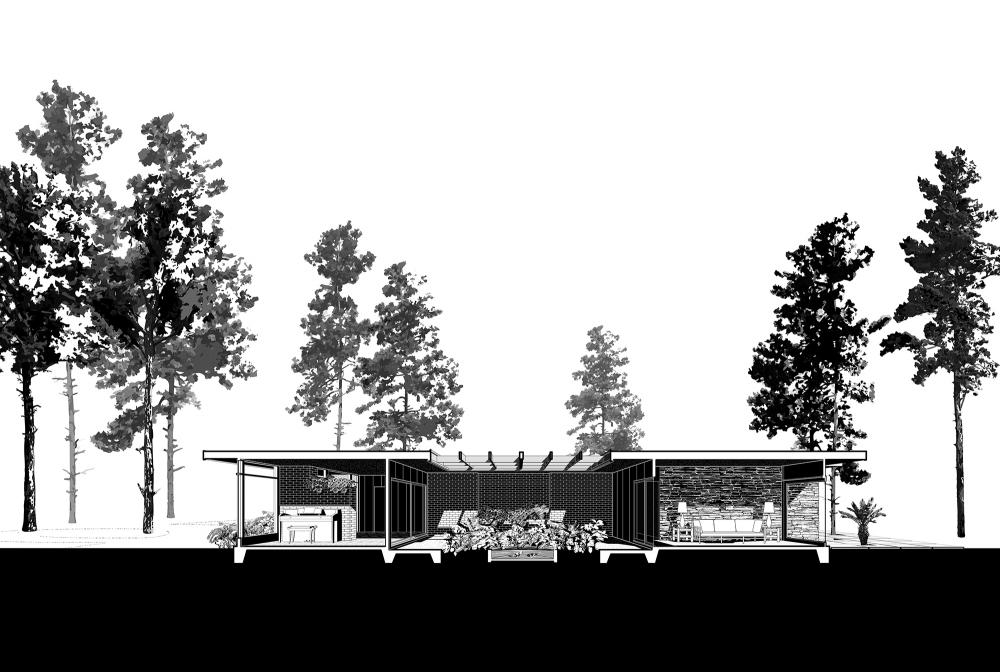

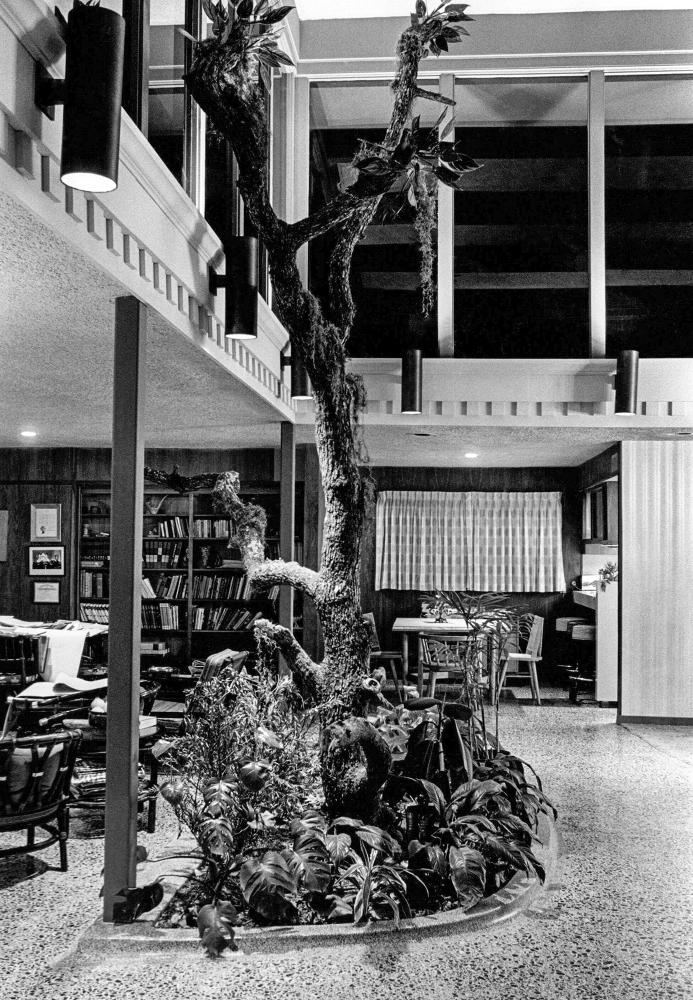

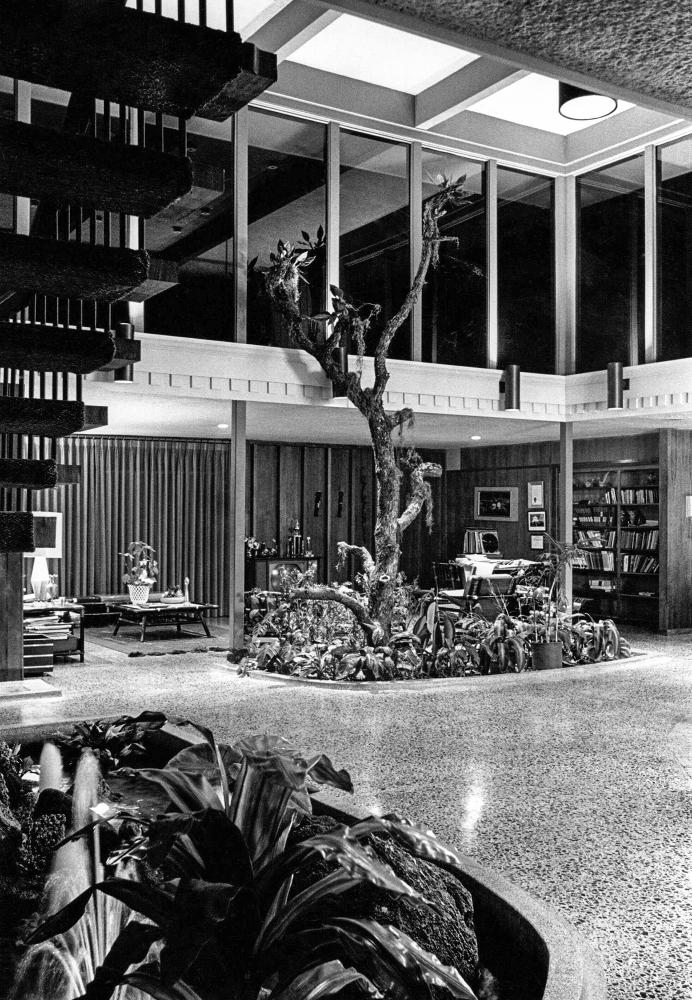

The Chase residence was completed in 1959. As Heymann contextualizes, the home was similar to other American courtyard residences in the 1950s, notably those made by developer Joseph Eichler in California, but rare in Houston. What made the Chase Residence unique was its social organization. As an architectural move, the courtyard introduces a sense of social life into the home because it allows views through the joined rooms and serves as a place for gathering. Here, it is also an outdoor space: Chase used this space for experiments with gardening. A courtyard unites a home by making a "small house for a small family" feel large. It provides daylight and a place of centrality as the house's mysterious center. It is a “window to the sky.”

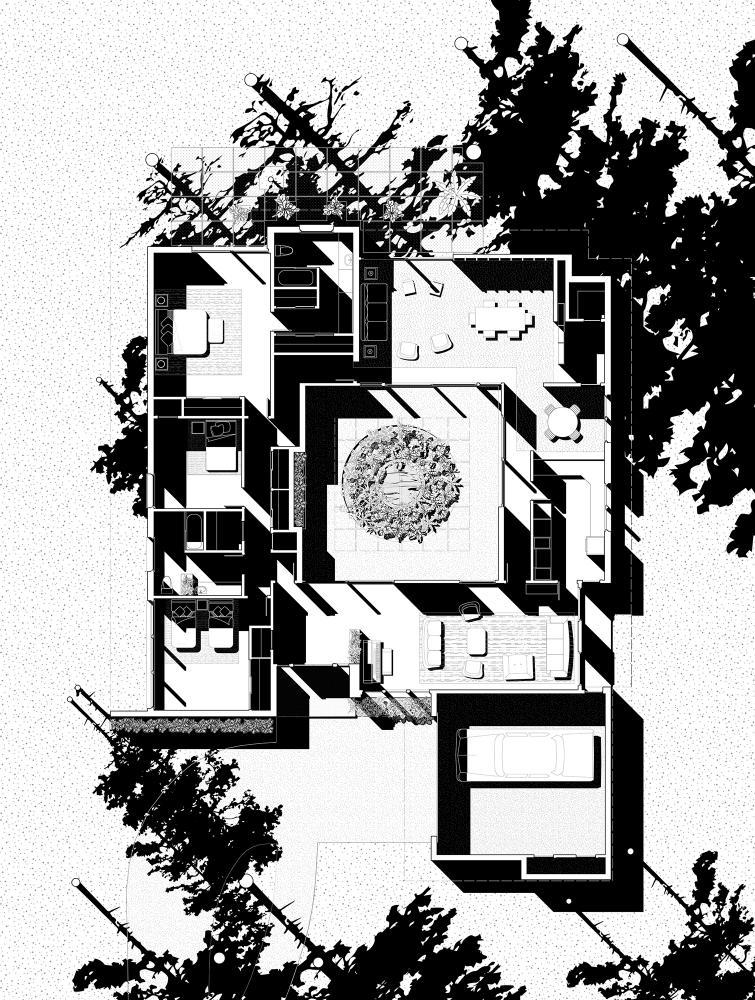

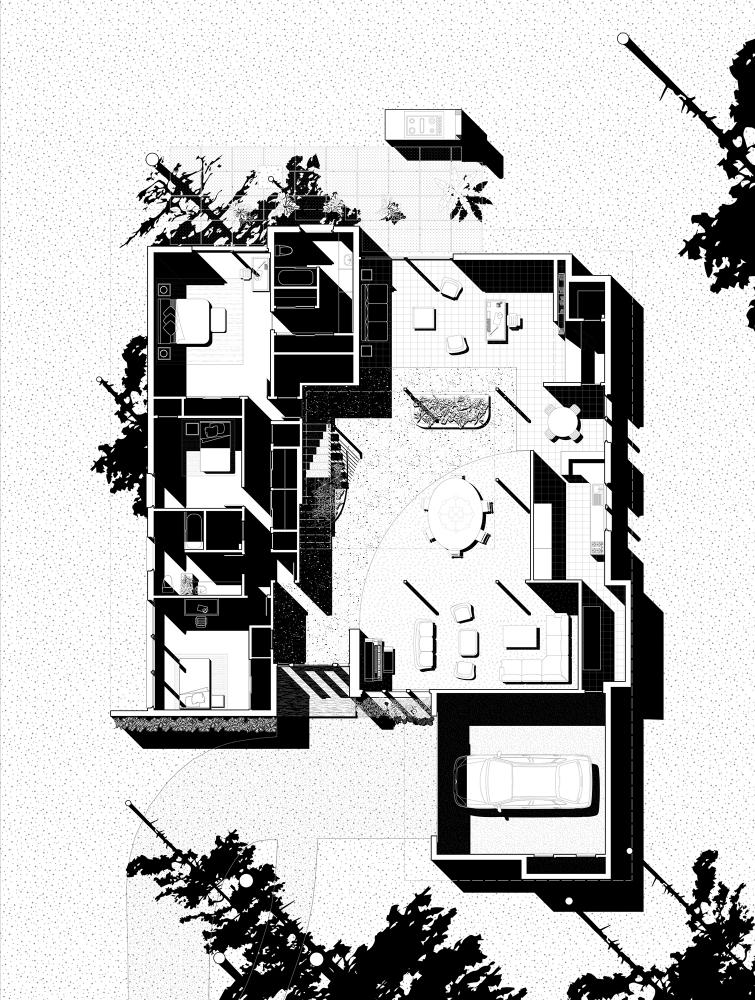

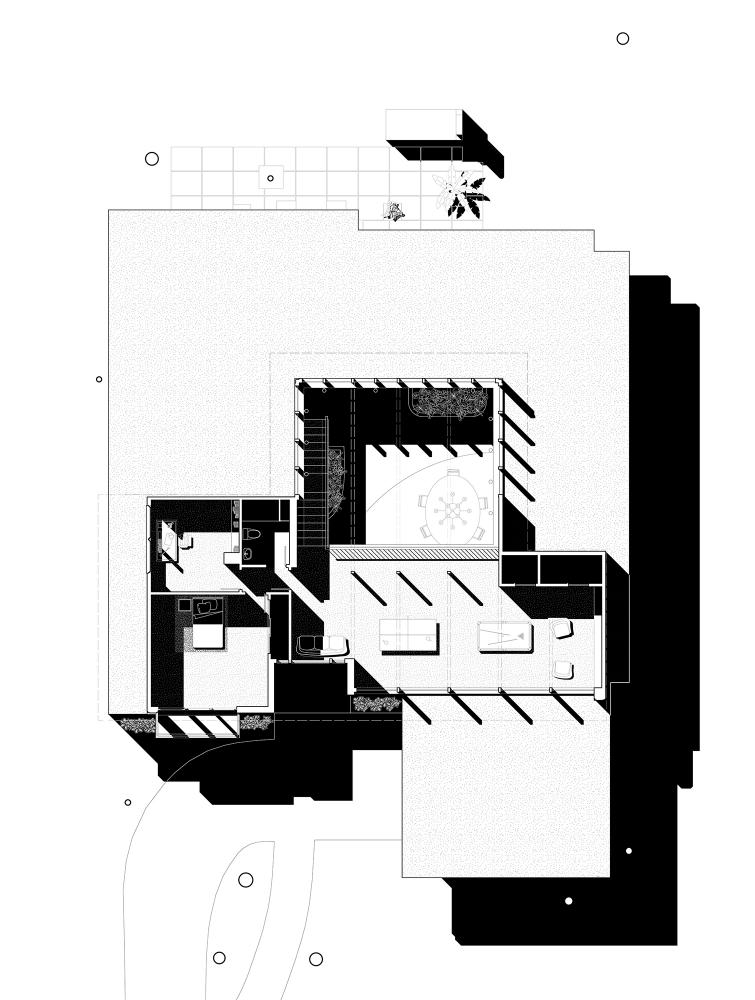

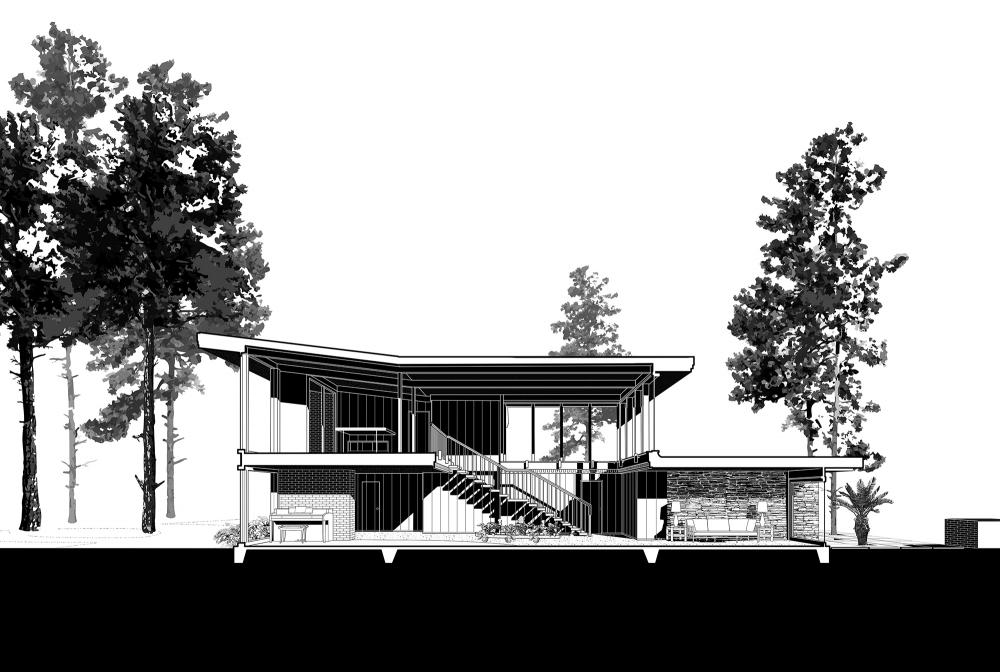

The book documents the home in two stages: Stage 1 (1959) and Stage 2 (1968). Both versions are explored through Heymann’s research and new drawings completed with his students. These new drawings help imagine inhabitation through their attention to the lived details of the residence. The drawings are precisely rendered in black and white, mimicking the historic photographs of the home. Color is only introduced when a family member appears in photographs. By not showing scale figures in the drawings or people in the photographs, the viewer is prompted to focus on architectural qualities like light and shadow. Heymann, in his written investigation, focuses on the partly shaded courtyard, a central piece of the house, and its subsequent renovation.

In Stage 2, Chase enclosed the courtyard and added a second story to the front part of the home. This new second floor was a place for his growing children and allowed him a small office at home. The courtyard, transformed into a grand living room, now possessed undeniable significance as a social space. This transformation corresponded with Chase’s success in Houston. Many notable citizens spent time here; in one photo, Mickey Leland poses with Saundria, Chase's daughter. Chase, “a natural-born progressive,” ran a large and successful firm that required continuous focused effort. Consequently, the great room was a safe space for socialization and personal expression. Naturally, a landing halfway up the stairs serves as an elevated spot from which speakers could address their assembled guests. Underneath, a fountain bubbled, reusing the same plumbing as the fountain in the center of the original courtyard.

Heymann’s research about both stages of the Chase Residence provides a clear appreciation of the house as an important work of architecture. Reviewing the photographs in the book reveals clear influences. In Stage 1, the filtered influence of Mies van der Rohe is felt in the use of white-painted fascia and buff brick, similar to designs used by other (white) architects in Houston. In Stage 2, Frank Lloyd Wright’s "confident populism" surfaces, most visibly in the new details of the roof and the windows upstairs.

These elements speak to Chase’s contemporary sensibility, but such observations doesn’t fully address the role of race in this history. While Chase learned from white architects, it is hard to imagine that he could freely visit and engage with their work in the city where he lived. Heymann reminds the reader that architects in Houston wouldn’t hire Chase because he was Black, and that he had to petition the state for special permission to take the licensure exam. He was only able to join the AIA chapter in Houston a few years later; the city’s architectural organization was, at that time, predominantly a social one, and therefore still segregated.

The home’s original design was abstract and quiet in its presentation of a one-story brick wall facing the street. Its "apparent normalcy" is offered to the reader, but such “normalcy” is the result of Chase's resilience and determination. While many important homes in Houston have been demolished, this one still stands, a testimony to the Chases’ perseverance. The Chase Residence is on par with any of the more well-known modernist houses from 1950s Houston, a claim reinforced by Heymann’s closing image in the book. In this photograph, a nice car sits out front while the handsome home is shaded by a thick tree canopy. The only difference from photos we’ve seen before is that the figure standing on the porch in the distance is Black.

As a closing section of the book, Stephen Fox’s essay “The Architecture of John S. Chase” adds perspective via an overview of Chase’s career. Fox provides a survey of the many projects completed by Chase’s office, notably the buildings for Texas Southern University. Even in this slender book it is clear that Chase faced racial prejudice, segregation, and systemic discrimination, but he overcame these conditions with a seemingly endless reserve of grace, modesty, charm, and determination.

Chase’s career is an example of how an architect can positively shape the world despite the presence of structural bias. However, he remains unknown to non-architects, and even to architects who don’t live in Houston. This ought to change, as Chase’s story provides a much-needed example to designers who are just starting their careers. Hopefully John S. Chase – The Chase Residence will become an essential reference for younger generations of architects like myself. I moved to Houston from Dubai in 2016 to pursue my Master of Architecture degree at Rice University. My undergraduate architectural education at the American University of Sharjah, the United Arab Emirates, was greatly influenced by and focused on American and European architecture. For a long time, architects presented to me as a student were mostly white men. I began to research architects of color in my last year of graduate school. I ended up discovering NOMA and recently joined its Houston chapter as a Communications Co-Chair. This book's publication is so crucial and timely to me personally and professionally. As an immigrant, a person of color, and an architect in the making, I recognize the importance of learning the hidden tales of my profession and honoring those who came before me.

Mona Elamin is a Sudanese architectural designer based in Houston. She received her Master of Architecture from Rice University and her Bachelor of Architecture from the American University of Sharjah. While pursuing her degree at Rice, Mona was the managing editor of PLAT, a 2017 recipient of Graham Foundation grant and a 2019 participant in the Oslo Architecture Triennale. More recently, she joined the Houston chapter of NOMA as its Communications Co-chair and helped produce this year’s Project Pipeline camp, which took place virtually.

John S. Chase – The Chase Residence is available for purchase now via Tower Books.

RDA, with a coalition of partners, will host The Chase House Remembered: Tony Chase and Saundria Chase Gray in Conversation with David Heymann on January 14, 2021. Register for the event here.