The new Glassell School of Art building is not subtle. At the media preview, Gary Tinterow, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston director, called the building “muscular.” The designers Steven Holl and Chris McVoy called it the most tectonic building that Steven Holl Architects has ever designed. The only decorative embellishments, Holl quipped, are the door handles.

Houston has a set of museum buildings to admire for their subtlety at the Menil campus, and the "radically understated" Menil Drawing Institute will push that tradition further. At the MFAH, lay people and critics alike will get a wow. The Glassell “demands attention” as David Heymann wrote in his review of the plans in the Spring 2015 issue of Cite.

Heymann’s history and descriptive analysis of the master plan, the Kinder Building (currently under construction), and the Glassell School of Art is below:

The new Kinder Building will be built on what has always been the logical place for the MFAH to expand: the parking lot next to the Noguchi garden on the north side of Bissonnet, directly across from Mies’ curving Brown Pavilion of the Caroline Weiss Law Building. Long the parking lot for the adjacent First Presbyterian Church of Houston, this open parcel is an inadvertent, ill-defined hole in the center of the campus. In 2007 the MFAH was able to obtain the land from the church—it continues to serve as a shared parking lot. In 2008 the MFAH set about establishing a shortlist of architects to design a new building in which it could finally bring together its twentieth and twenty-first century holdings—the art that tracks the rise and apotheosis of Modernism and its complex fallouts. (The new building is not designed for major traveling exhibitions, which will mostly continue to go to the Brown Pavilion.)

In 2012, three firms—Steven Holl, Snohetta, and Morphosis—presented conceptual site plans and proposals for the architecture of the new building. Holl was hired to proceed. Since the site purchase was tied to an MFAH commitment to provide parking for the church—and the new building itself requires substantial parking—the brief the architects were given included the design of a new, eight- to ten-story parking tower on lots the MFAH owns just to the north of the existing Glassell School, which was to remain. Both Snohetta and Morphosis included this garage tower in their designs. But Holl proposed an alternative, counter to the brief: bury all the parking in two garages, one under the new Kinder Building, the other under an entirely new, expanded Glassell School ...

Set above two stories of underground parking—part of which serves as an art forum from which a tunnel links to the museum—the “L” of Holl’s three-story Glassell is organized around a skylit, stepped concrete theater/gallery/atrium/stairwell at the joint between its two legs. These legs house studios classrooms, and support spaces along double-loaded corridors …

The school’s elevations are composed of vertical precast concrete panels assembled in a regularly irregular pattern of parallelograms and trapezoids (a familiar current trope, with enough shapes repeating and reversing so you cannot perceive an order). Large expanses of translucent OKALUX glazing span between the precast panels. The panels and glazing are set variously along, at an angle to, or in from the edges of the exposed concrete floor slabs. The overall effect demands attention—perhaps more than any other building in the complex. That will likely work well against Jimenez’s restrained Administration Building across the street. New trees along the street edge will further bind the plaza—partly intended for the display of sculpture—and the Noguchi garden....

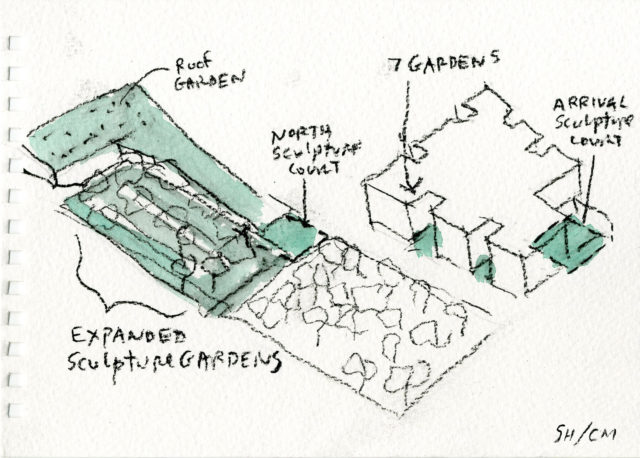

Watercolor of Glassell School and Kinder Building; Courtesy of Steven Holl Architects.

Watercolor of Glassell School and Kinder Building; Courtesy of Steven Holl Architects.

Cite will publish a full response to the Glassell building after students have had a chance to spill paint on the floors, public exhibitions and performances have animated the atrium, plants have grown in a bit, and the Kinder Building and Fayez S. Sarofim Campus are complete. For now, I am sharing a few initial reactions from the media preview.

Even in its partially completed phase, the new MFAH campus is a remarkably optimistic expression of what a museum funded through donations from foundations, individuals, and corporations, plus some public dollars, should be in the twenty-first century. The MFAH is not simply a container of culture. It is not just a series of galleries that school children cycle through to get a taste of art history. It goes beyond the museum store and cafe as interactive spaces for the public. The Brown Foundation, Inc. Plaza and the dramatic “forum” inside the Glassell are meant to bring together the full spectrum of the Glassel’s pre-K through postgraduate adults with a broad public through partnering institutions like the Houston Public Library.

Interior view; the forum of the Glassell School of Art; Photograph courtesy MFAH, © Richard Barnes

Interior view; the forum of the Glassell School of Art; Photograph courtesy MFAH, © Richard Barnes

In his Spring 2015 interview for Cite, Holl noted, “The social mission of museums has grown steadily in the last 100 years to make them ‘social condensers’ of modern urban life. For these missions, it is one of the finest commissions for an architect today.”

Since that interview, the sense that the social fabric is fraying in the United States has only intensified. Can the MFAH save democracy and bring together people of different backgrounds around art that challenges the world as we accept it? That’s going too far, of course, but overstating the question helps get across how important the aims are.

This building and landscape should withstand heavy public use. The precast trapezoidal concrete panels that hold up the building are thick, even daunting, like the elemental building blocks that hold up Cusco, Peru. The new Glassell is a sturdy, economical, and utilitarian icon. That is also to say that the building and plaza feel rough — severe in places. The day of the media preview was hot and the sunlight strong. I did not linger in the plaza. Inside the light was a bit too intense in a few rooms even when filtered through the giant translucent glass panels. Time, use, and growth are likely to soften things up.

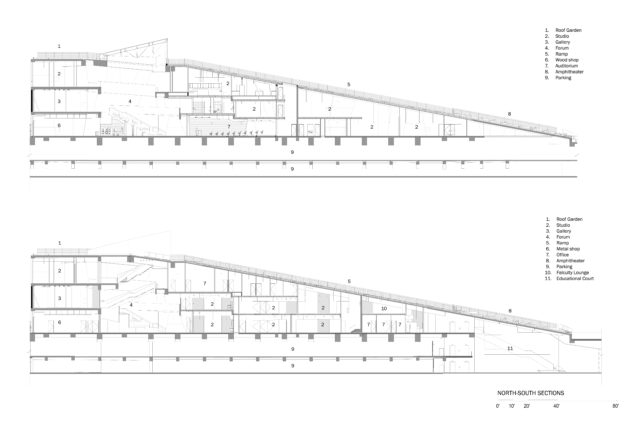

Overall Glassell School of Art Building Sections. Courtesy MFAH.

Overall Glassell School of Art Building Sections. Courtesy MFAH.

The biggest wow comes when you ascend to the BBVA Compass Roof Garden. (I was ushered up the stairs and did not experience the sloping roof.) When not in use as an event space, the roof garden will give Houstonians a much-needed free perch. This city is full of towers but none that I know of offer a public viewing deck at this time. To have a few elevated spaces where you can observe and try to make sense of this flat, messy place is important.

And what do you see from up there? That particular view is lovely—a city in a forest. Houston looks coherent. You see a mix of old and new architecture. The Southwest Freeway is sunken and out of sight. Houston looks like a place you would want to stroll. Aside from how lethal some key intersections and corridors in the area are, the Museum District is as lovely as it appears from up there.

Level 1 Glassell School of Art Floor Plan. Courtesy MFAH.

Level 1 Glassell School of Art Floor Plan. Courtesy MFAH.

In Houston, when our extraordinarily generous corporate and philanthropic communities come together, we can have it all — great architecture, plentiful parking underground, plazas, art, trees, cafes. Once the Kinder Building is complete and aglow, I think there will be a sense of Houston having arrived, or reached some new threshold of cityness. People from all over the region, many coming from neighborhoods that lack anything close to a healthy public realm, will at least be able to come to the MFAH (free on Thursdays). To be sure, Houston philanthropy is focused on equity in the Third Ward and across the city through Bayou Greenways 2020, SPARK parks, GO Neighborhoods, and many other initiatives.

At the media preview, BBVA Compass President and CEO Onur Genç underscored the multinational bank’s commitment to local community development. From the roof garden, looking down at Anish Kapoor’s “Cloud Column,” a gorgeous sculpture that is as confounding as the “late capitalist” or “neoliberal” economy we all participate in — it’s hard to understand why resources can be so scarce and abundant in such close proximity — I could not help but feel elated about being in the middle of a grand moment, a condensation of so much energy and talent.

Raj Mankad is the editor of Cite. An excerpt of David Heymann’s Spring 2015 article "A Binding Debate Renewed: Steven Holl's Buildings for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston" that focuses on the Kinder Building is available here. The interview of Gary Tinterow and Steven Holl is available here.

Additional Reading

Papademetriou, Peter. Loose Fit: The Houston Museum District." Cite: The Architecture + Design Review of Houston, issue 34, Spring 1996.

el-Dahdah, Farès. "Sheddling Light on the Beck: Rafael Moneo's Audrey Jones Beck Building is a Lesson in Opacity and a Connection to the Architectural Past of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston." Cite: The Architecture + Design Review of Houston, issue 47, Spring 2000.

Self, Ronnie. "Counterpoints: Big Wisdom and Small Wit May Put Houston Back on the World Stage for Architecture." Cite: The Architecture + Design Review of Houston, issue 89, Summer 2012.Frampton, Kenneth. Steven Holl, Architect (2002: Milan, Electa; dist.: Phaidon).

Blundell Jones, Peter. Hans Scharoun (1995: London, Phaidon Press, Ltd.).

Firms

Design Architect: Steven Holl Architects, NYC

Associate Architect: Kendall/Heaton Associates, Inc., Houston, TX

Landscape Design: Deborah Nevins & Associates, Inc. in collaboration with Nevins & Benito Landscape Architecture, D.P.C., New York

MEP Consultant: Icor Associates, LLC, Iselin, NJ

Structural Engineers: Cardno Haynes Whaley, Houston, TX; Guy Nordenson and Associates, NYC

Civil Engineers: Walter P Moore & Associates, Houston, TX

Construction: McCarthy Building Companies, Houston, TX

Project Management: The Projects Group, Fort Worth, TX