This article by Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne [@HawthorneLAT] appears in full in Cite 96, a special issue on museums also featuring Walter Hood, David Heymann, and Ronnie Self, as well as interviews with Steven Holl, Gary Tinterow, Johnston Marklee, Josef Helfenstein, Linda Shearer, and others. The issue is available at bookstores and to subscribers.

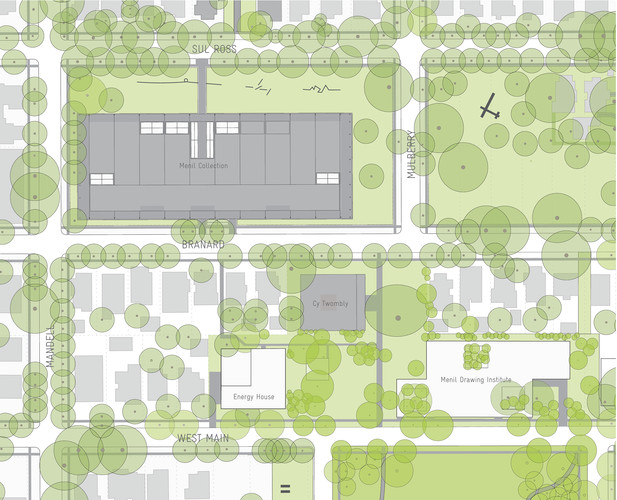

The master plan that the Menil Collection in Houston is relying on to guide its own expansion seems not just genuinely but almost radically understated. Produced by David Chipperfield Architects, the plan emerged from an invited competition overseen by Josef Helfenstein, the director of the Menil since 2004, and was approved by the museum’s board in 2009. It calls for measured growth over time, one small standalone art gallery at a time, along with the addition of a café and expanded parking lot. It does not call for a grand new central building or a linked collection of impressively scaled wings. Nor has it been a vehicle for the museum to correct or flee from the perceived missteps of other capital projects or smooth over the errors of earlier architects, directors, and boards of trustees, as has arguably been the case at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), the Whitney Museum of Art, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, or the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), to name just a few in what has grown to become a very long list of art-world institutions plagued by that kind of intergenerational architectural regret.

The master plan is instead a document intended to build on and indeed safeguard the considerable, singular appeal of the museum’s original gallery building, designed by Renzo Piano and opened to the public in June 1987 --- as well as the bungalows from the 1920s and 1930s that line the edges of the museum campus and the simply treated landscape, made up mostly of grass, substantial oak trees, and a small handful of artworks, that holds the 30-acre parcel together.

The Chipperfield master plan, in fact, attempts to add new structures to the Menil campus very much in the image of the quietly astonishing Piano building, which remains with the Beyeler Foundation in Basel, Switzerland, the finest artworld design of the Italian architect’s long career. The model is clear: the horizontal, usually single-story, gallery building set into that green landscape and visible in the round. Quite carefully the master plan also seeks to stitch the museum campus more securely into the urban fabric and to the surrounding city grid, strengthening the sense of a north-south axis through the site and looking ahead to the day when a light rail line will be finished along Richmond Avenue, on the Menil’s southern edge, changing the way visitors approach the museum and its relationship with the rest of Houston. In the methodical and unflashy nature of its approach to expansion, the Menil is matched among American museums perhaps only by the Clark Institute in Williamstown, Massachussetts, which unveiled an expansion by Tadao Ando and Annabelle Selldorf in 2014.

At the same time, the Chipperfield plan holds the potential to produce some of the most important museum buildings of the first few decades of the twenty-first century. And in fact it is this relationship between institutional caution and architectural ambition that I am interested in exploring here. Paradoxically enough, it turns out that the sobriety of the Menil’s expansion efforts and Helfenstein’s leadership style more broadly have been key elements in helping the museum become a patron of searching, innovative architecture. The first building proposal to come out of the master plan process, Johnston Marklee’s Menil Drawing Institute (MDI), is evidence of this productive relationship between caution and experimentation. It is a design that appears spare, even plain, at first glance and reveals layers of complexity, surprise, and risk-taking the more it is studied.

[...] Their scheme is a deft and timely marriage of abstraction and rich allusion and incorporates a number of domestic, residential metaphors. (The main circulation and gathering space will be called the Living Room.) The MDI will be more approachable, more domestic in scale, than a typical museum wing but certainly grander and more ambitious in circulation and in how it treats display than a house. Most impressive of all is how, in making room for three courtyards, each containing an existing oak tree, and in connecting to the Menil landscape, the design bears in mind a key lesson about visiting museums that too many architects forget: that the transition from inside to out, from the intensity of concentrating on looking to the pleasure of concentrating on nothing at all and merely feeling the sun or the rain on your skin, can be more crucial than the transitions from one gallery to the next.

The MDI will offer a test of Johnston Marklee’s ability to turn promise and a thoughtful approach to expanding a practice into a persuasive collection of built work. The architects made some compromises in order to maintain the MDI’s modest single-story profile, rising no more than 16 feet; roughly half of the building’s 30,000 square feet of interior space will be located on a basement level, dedicated mostly to art storage. This can’t have been an easy sell for curators and conservationists concerned about flooding and other possible damage.

Above ground the design is an extended architectural essay on one kind of design characteristic nestling within its opposite. The MDI is meant to be filled with dappled light, strategically mediated by the roof and the oak trees, in some rooms (especially the Living Room) and nearly paranoid about light levels, to protect works on paper, in others. Some interior spaces will be spacious enough and faced with glass to feel open-air, while its courtyards, lined vertically with wide cedar planks, will feel like interior rooms. The roof, formed from an unusually thin steel plate, lends the building a spare, modernist personality from certain angles; but inside the faceted ceiling suggests a gabled geometry.

That is a lot of complexity and metaphorical layering to pile into a building that will contain just 17,000 square feet of above-ground space, which is smaller than many houses in Houston’s higher-end residential precincts. It will be a real breakthrough if the final product lives up to the renderings: A building packed into a manageable scale in contrast to the wan, attenuated, oversized wings so many other museums are building. A gallery building that feels thick with architectural ideas and gives consistent access to the outdoors, that leaves you wanting more instead of fighting off gallery fatigue? That is a rare concept these days.

Thomas de Monchaux, writing in Architect magazine, suggested that the building might prove to be a bit too well-behaved in the end for the unruly complexity of Houston. Yet in certain ways the MDI design’s Trojan-horse qualities --- the way it cloaks its experimental streak in rather reserved outer dress --- make it especially suitable for the Menil campus, which has long operated as a both quiet refuge (for Houstonians and visitors alike) and a proving ground for new approaches to museum architecture.