Sarah Nichols, Assistant Professor of Architecture at EPFL in Lausanne and former Assistant Professor at Rice Architecture, curated and provided the scientific direction for Beton, an exhibition at the S AM Swiss Architecture Museum. The exhibition explores the complexity of understanding concrete, a widely used building material, and presents original drawings, models, and photographs from the three main architecture archives in Switzerland. Nichols spoke with former Cite Editor Jack Murphy last month about the exhibition, her dissertation work, teaching, and practice.

Beton is up at S AM in Basel until April 24th, 2022. The exhibition catalog is featured in Concrete in Switzerland (EPFL Press, 2021) and a virtual tour of the exhibition will be made available at a later date.

Jack Murphy: Can you tell us about the background of the S AM Swiss Architecture Museum exhibition, Beton?

Sarah Nichols: The exhibition came out of a funding crisis for the museum. The Swiss federal government only considers an institution to be a museum if it has its own collection, and the Swiss Architecture Museum doesn't have one. As a way of addressing this, they formed a partnership with the three main architecture archives in the country—ETH Zurich’s gta Archiv, EPFL’s Archives de la construction moderne, and USI’s Archivio del Moderno dell’Accademia di Architettura—which represent the three main architecture schools and the three main language regions in Switzerland. To inaugurate this new collaboration, there was an idea to do one project together.

It's important to understand that the idea of bringing together the three regions is a contentious proposal since there isn’t much national identification for architects in Switzerland. For example, Olgiati would say “I'm from Flims,” or Zumthor, “I'm in Graubünden,” but not “I'm a Swiss architect,” even if that is how they are seen from the outside. For the project’s theme, someone proposed concrete as something that Switzerland is renowned for in terms of architecture and engineering, and also as something that ties the country together. I was brought on since I had already been working on my PhD as a history of concrete in Switzerland.

Could you talk about the exhibition and its conceptual framework?

The origin of this exhibition was to display the archival material. It was important to work deductively, asking what we have and what can be built out of what we have. I also had an innate reaction to steer away from redividing everything, whether as a positivist history of eras or as assigning a room to each region and archive, since doing so defeated the possibility of truly working together. My research assistant Ziu Bruckmann and I looked through over 10,000 pieces of material from the archives, sorting and grouping them according to their significance. From this process, the idea developed to organize the material around nine stories—nine myths that have shaped our understanding of concrete.

Do the myths imply that they are misleading in some way?

For the exhibition, I was thinking of myth or story as having a kernel of truth or a truth that someone wants to convey, but also exaggerated such that the mythic becomes an actor on its own. "Concrete is rock," is one of the nine stories: if you talk to a geologist, they will say, “Yes, obviously concrete is a rock. An anthropogenic rock, but a rock all the same.” However, architects initially didn’t know what to do with modern concrete because it was poured into place. Positioning concrete as a rock was a way of putting it within the tradition of architecture, creating possibilities for how to understand and treat the surface, and how to give the material an aesthetic. The other stories include “Concrete is energy,” “Concrete is composite,” and “Concrete is fluid.” It’s intentional that the nine stories don’t add up. There are contradictions, and at times overlaps among them.

How were the stories turned into the exhibition space?

The exhibition asks the audience to do a lot of work because the material is not organized by region, era, or author. The audience has phrases like, “Concrete is rock” in their heads as they look at the exhibited material, which consist of disparate projects from disparate areas. In doing so, they understand the exhibits as a group and the different ways in which each myth has perpetuated through time. This is not the easiest way of asking someone to go through an exhibition, especially considering the large amount of material on display.

Because so much was already being asked of the audience, it was extremely important that the scenography is didactic. We worked with Graber & Steiger Architekten, who did amazing work pro-bono, to put together a series of “cabinets” so that each story had its own room, clearly defining the bounds of each story in the exhibition space. They also came up with the idea of using formwork elements to incorporate the feeling of a construction site. Because the main exhibition space consists of three rooms in enfilade, they inserted two parallel formwork walls through the enfilade that cut across the three rooms, and then added a couple of perpendicular walls behind the formwork walls to produce the nine cabinets. The idea is that when you are circulating, you are circulating through the space where concrete would be poured—you become the concrete.

The exhibition is closing at the end of this month. Have you had any feedback from the museum about how it has been received?

It seems like the number of visits has been off the charts, and the museum is receiving more private tour requests from school groups or offices than usual. There has been some discussion in the press about whether it’s appropriate and worth anyone's time to look at an exhibition on concrete today, when we understand how severe the ecological consequences of using the material are. I don't consider the exhibition to be a love letter to concrete in any way. There is, of course, spectacular architecture and an era of grand ideas, which I think we can look back on with very mixed emotions. We worked quite hard to include a wide range of narratives, in particular debates about the material’s worth and the discomfort with its prevalence.

Are there ecological ideas in the exhibition that talk about the carbon footprint concerns? How does the exhibition deal with that legacy?

It does, but probably imperfectly. I had my historian hat on for this exhibition and it was important to communicate to a present public the ideas and discussions that were relevant at the time, rather than heavily laying on a narrative of how we should interpret them today. It was a challenge that I was aware of while working on the exhibition. If we only include material from the architecture archives, there will be next to nothing about the ecological impact of concrete or the hatred of the material’s aesthetic. We tried to include ecological narratives by incorporating artifacts from other archives that dealt with energy use figures and public reception (posters, protest photos, fuel consumption data) rather than through adding a strong hypertext layer.

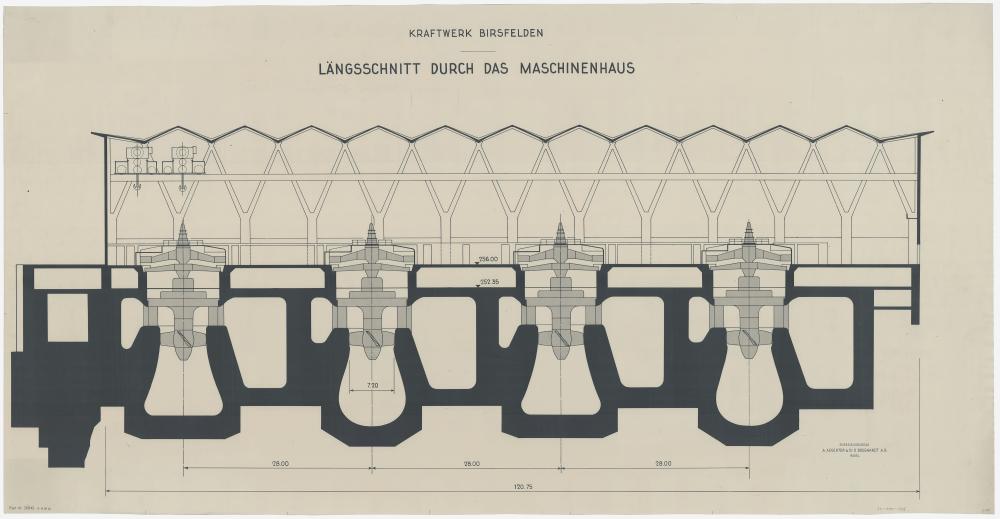

For example, the room of "Concrete is energy" was intended to provoke shock on concrete’s reflexive relationship with the increasing energy production and consumption. There is a section drawing of the well-known Kraftwerk Birsfelden power plant, which is a river power plant outside of Basel designed by the modernist architect Hans Hofmann. The building is a filigrane structure that sits above the water level, but the section shows what is visible above ground in relation to an incredibly massive piece of concrete that directs water into the turbines. The concrete is rendered completely in black and absolutely dwarfs the building above.

The exhibition has quite a bit of material about cement production and the amount of fossil fuel that is required in order to produce concrete, including critical films that address the farther-flung consequences of what happens when we are, essentially, concreting the territory. I would say it was an imperfect attempt.

Are the films produced for the exhibition or archival footage?

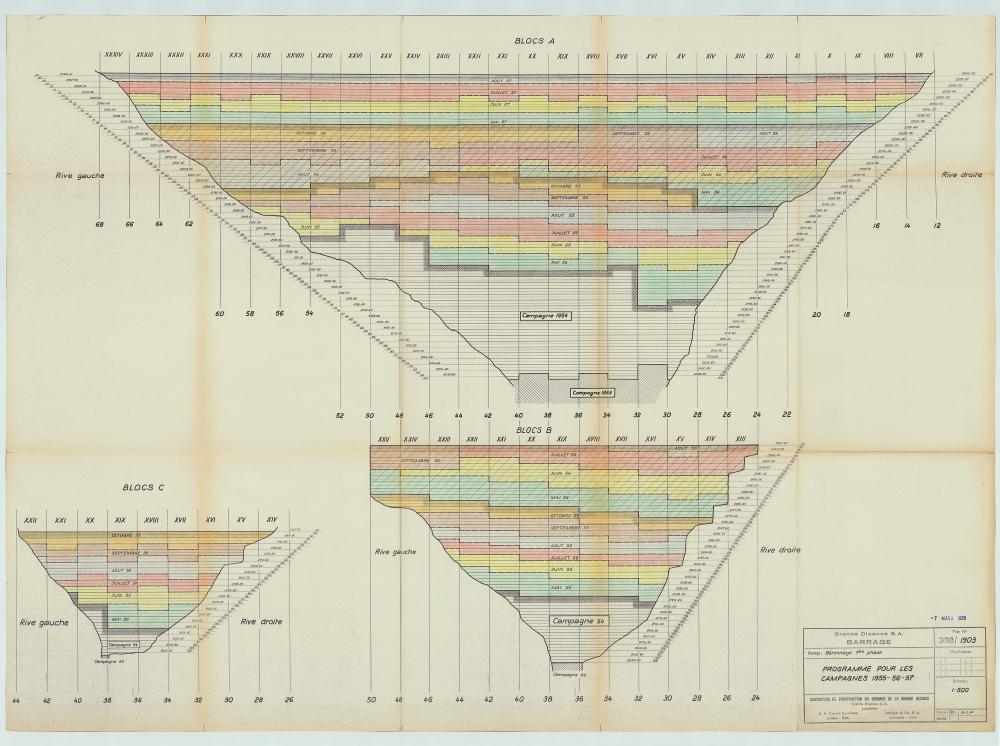

There are archival videos and films, including the two at the exhibition’s entrance. One is Jean-Luc Godard's first film, Opération Béton (1958), which is about the construction of a very large and remote Alpine hydro-power dam called Grande Dixence Dam. It is frighteningly enthusiastic, showing the process of producing concrete by ripping up the glacial moraine, turning it into aggregate, and pouring this dam. This film is in contrast with the lesser-known film by Swiss filmmaker Fredi Murer, Grauzone (1979). In the film, there’s a malaise spreading through the city, and the city is causing people to lose their memory, purpose, and spontaneity. It's a very hard implication of concrete and more generally, of postwar development.

JM: What does an exhibition reveal that may not be captured in a publication or other media?

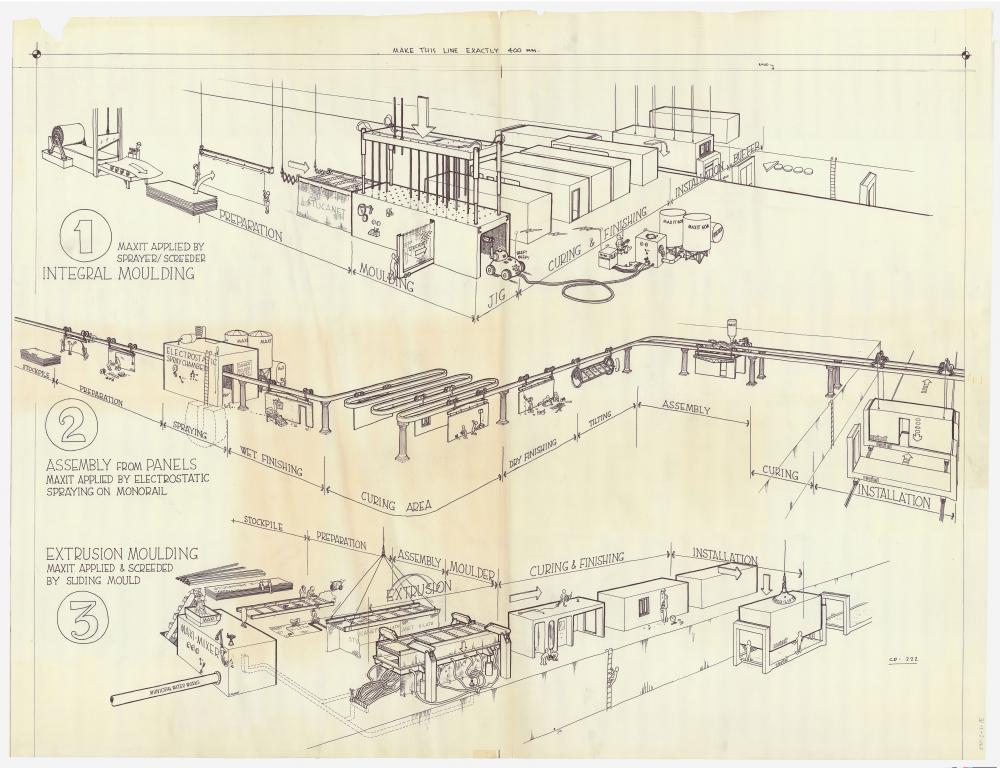

We were able to show a lot of originals, which is not always the case considering their fragility and sensitivity to light exposure. The pieces have been framed so that you can see everything up to the edge of the drawing. Not only are you able to see much more details than from a reproduction of a book or forms of most web representations, you’re also able to see the marginalia and understand what it meant to produce architectural representations during these different times. There would be scratches of repeated graphs in the edge of a drawing that came from the author trying to get the ink to flow again, or little notes from one team member to another. There is the beauty of the drawings themselves, but also of the sub-histories that reveal the production of architecture. One of the drawings is over ten feet long. The drawing is reproduced in the catalog, but it effectively becomes a diagram of the actual drawing. An exhibition also made it possible to integrate different media and show them in juxtaposition with one another. To have a physical model, a video, and a drawing side-by-side was a special way of working where I did not feel constrained.

Even as a set of regions combined into Switzerland, is there a national relationship to the material? What, if any, national idea is shown in the show?

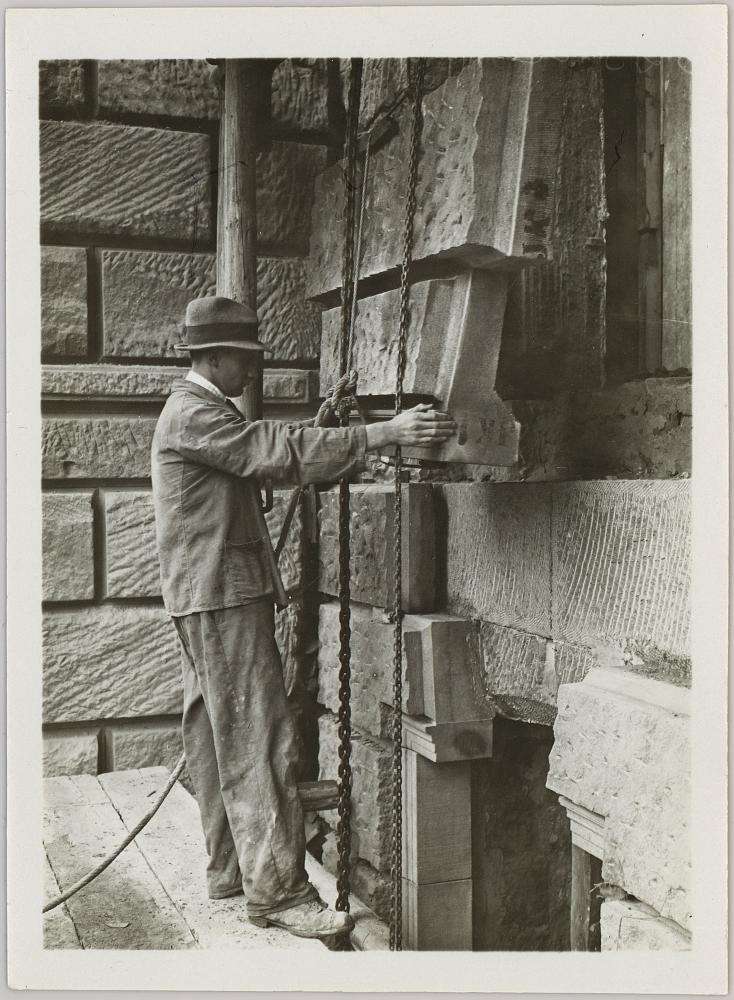

In the show, not much. It's a question that frequently comes up, also in relation to my dissertation work. I admit that it's one that I’m not interested in because I see it as one local permutation of a global material. The exhibition did not seek to explore what is specific about concrete in Switzerland, and it was more of a local meditation on the material itself. With that said, the national scale is important because materials such as concrete were mostly regulated with national norms and material production for much of the twentieth century, and this was certainly the case for concrete in Switzerland. By the outbreak of World War I, Switzerland was already the wealthiest country in Europe per capita, and there has been a lot of focus on the quality and the durability that allows ultra-high construction budgets for long-lasting buildings. This played into the concrete producers’ rhetoric that this is a material for the long that is extremely robust. There are also links that can be drawn in terms of the tight control of engineering education, the site supervision, and the skilled work on the site.

What was the make-up of the curatorial team and what was your role?

The museum director and the exhibition’s artistic director, Andreas Ruby, was responsible for commissioning the scenography and developing the public program surrounding the exhibition. I led the research and the academic contribution of the exhibition, selecting the material and developing how it would be organized. The curation was done in collaboration with the museum’s curators, Yuma Shinohara and Andreas Kofler. My research assistant, Ziu Bruckmann, who is now my collaborator at EPFL, took on quite a bit more than initially intended as I was stuck in Houston during the pandemic—we developed a way of working virtually to make sure that the project could keep progressing.

We also relied on the expertise of the three archives. One of the challenges of doing an exhibition with the archives is that they are not as indexed as a library—there was no way of searching and identifying the projects made of concrete. For some projects, there may be a couple of photos and some drawings. For other projects, there are boxes and boxes of material. Even if there is a project that’s entirely out of concrete, you don't know which drawings are going to be significant. We were not necessarily selecting the iconic drawings of a project and rather selecting drawings that reveal something about the material in a different way. We were in constant conversation with the archivists and very much reliant on their generosity and expertise.

If the show is an archival exploration, what do you think are the lessons or values for architects seeing the show?

I don't know if there is one clear narrative, but there were a few points that I wanted to get across, with one being that the link of concrete with modernism is totally fabricated. Concrete was already becoming prevalent before modernist architects began to use it, and there is a rich history of historicist architecture made of concrete. There is something deeply linked to modernization and modernity in reinforced concrete construction, beyond what is added as modernist architecture.

In terms of practice today, we don't talk enough about the conditions that govern the way we build. In my dissertation, I became really interested in the conditions of architectural practice, thinking about what links us to the other parts of the building industry and understanding the mechanisms behind how we got here. If we talk about concrete being ubiquitous today, how did that happen? The newest pieces in the exhibition are from the 1990s, which is already history. There needs to be more reckoning about the difference in how we perceive the material today versus how much has changed in practice.

You mentioned that the exhibition is different from your dissertation. Could you share about your dissertation work, and the publication that's upcoming?

It felt almost indulgent to concentrate on the objects themselves for the exhibition. What I look at in the dissertation is more systemic; it's more about the political economy of concrete. I look at the emergence of concrete as a modern material (I say modern to distinguish it from ancient Roman concrete and other forerunners) and as an industrialized material that was produced en masse and standardized. It became easily available through large-scale, capital-intensive means of production. I follow concrete from the nineteenth century when it was almost a novelty and very little was being used for architecture, through to the postwar period when concrete essentially escapes the regime of scarcity—something in relation to which architects have always understood building materials. I argue that by then, concrete had become a material without limit, especially in Switzerland. In 1972, Switzerland’s per capita use of cement, which is the best index for concrete use, was just under 1,000 tons per inhabitant per year, higher than anywhere else in the world.

I look at the way that the structure of institutions, both the national material testing labs and the cement industry (which used to be a legally recognized cartel) formed and worked together to ensure consistent availability of concrete. I look at the discourse that convinced people, whether professionals or the lay public, that concrete was a material that was safe and desirable. There were a lot of false promises that never really disappeared, including its durability and protection against different threats. Finally, I look at the technical and chemical compositions of concrete and how they changed to make it possible to pour more and pour faster.

At Rice, you taught classes on building technology. How does your background and expertise shape your work as an educator?

What interests me about focusing on the physical building and its materials, as opposed to representation, is that it’s a site of different entanglements. It's the moment where our professional expertise meets all the other people and things that come together in a building. I really enjoyed working with the Tech III class at Rice to discuss what our responsibility is vis-à-vis the people who are actually building the building; our responsibility in terms of knowing where our materials are coming from, and how the knowledge opens up the different possibilities for design—which is to say, not only thinking about materials in terms of ethical questions, but also thinking about them in relation to how we design and what we might foreground in our design decisions.

At EPFL, I have a research unit on theory of environment and material in architecture, called THEMA. It will develop out of my existing work, incorporating contemporary research and expanding the focus beyond concrete. I will be teaching classes about materials theory, including a class called Before and After Construction. We will physically work with the materials, together with those from the building trades, so that we understand what it means to pour concrete or lay a brick wall. The class will think of the building and its materials as a closed loop, looking at everything from its occupation, maintenance, repair, to its renewal as aspects that should be considered in the initial design.

There is a different set of questions that comes up when you understand the architect in the larger ecology versus the architect as a visionary figure. What is important to you when you are designing as an architect and how do you design with all the awareness that you have?

I don't think that I have a perfect answer yet. Since I started engaging in these topics, I’ve only worked on two projects worth noting. One of them is a family project of a house in Germany. What was amazing about this project is that it made me want to throw out all discussions about details. We had no drawings for details, because we were working in a place where the construction labor is incredibly skilled. The builders would have been offended if we went to them as academically trained architects telling them how to build something. We would go to a construction trailer to sketch and discuss certain ideas, but we ultimately had no choice other than to work eye-to-eye with the builders. It made me question a lot of what had been drilled into me. I think our obsession with details often skyrockets the price of what we build—there's a fetishization of it—whereas the amount of time that we spent on details for this project was effectively negligible. In the end, the house was built and I'm 70 to 80 percent happy with it. If we had tried to control all those details, the budget would have been much higher and it would have been a much more complicated process.

Currently, I'm working in the complete opposite spectrum. The project is also a single-family house but in New Zealand. It’s for very experimental clients who want to do a lot of the work themselves but have no construction experience. I’m confronted with questions of when the formalized contractor steps off the site and how the house can be designed so that it can be finished by hand.

I don't think that there is an easy answer to your question because there is no universality to thinking about materials. There is so much local variation. There are local building cultures and norms that change the prices for material and the labor. Even the equations determining whether the material is sustainable or not change depending on the distance it is traveling and its production and transportation methods. I often feel like the awareness opens a lot more questions than solutions.

Sarah Nichols is Assistant Professor of Architecture at EPFL in Lausanne. Prior to this, she was Assistant Professor at Rice University School of Architecture. The exhibition “Beton” is up at S AM in Basel until April 24th, 2022. Her dissertation, for which she was awarded the ETH Medal, is a history of concrete in Switzerland that she is currently turning into a forthcoming book.