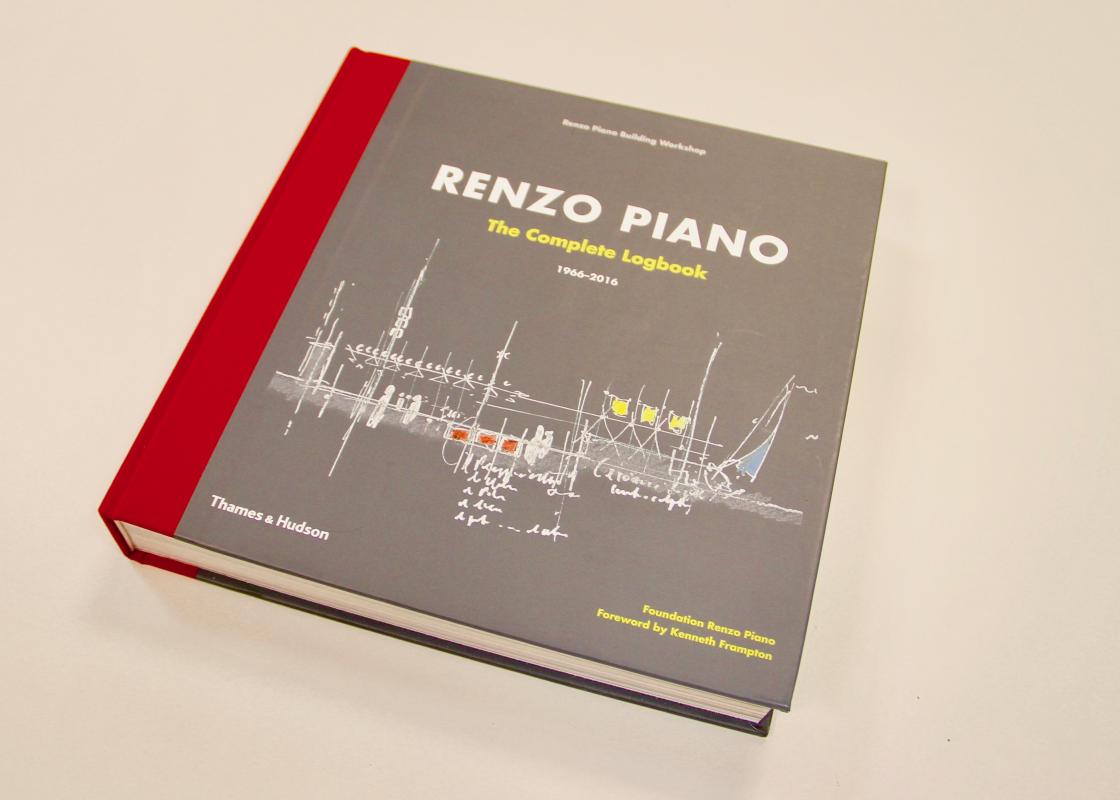

Renzo Piano’s The Complete Logbook was released in the United States this spring. It covers the period from 1966 to 2016 and includes over 70 projects documented with photos, drawings, and sketches and commented by the architect. An earlier version, simply titled Logbook, was published in 1997. It has a similar format and includes 50 or so projects along with an introduction, “The Profession of the Architect,” and a conclusion, “From Builder’s Son to Architect.” With these two valuable texts the Logbook tends toward an architectural treatise where Piano prescribes what buildings and cities should be like and then illustrates his values with his own designs. The opening and closing texts are interesting and revealing and address issues that most all architects grapple with. They are not overly cerebral or theoretical but give insight into what makes Piano tick. I often assign these texts and discuss them with my students at the University of Houston.

Piano’s outlook is optimistic. For him the practice of architecture is an adventure and a journey, and architects are, or should be, today’s Christopher Columbuses (Columbus and Piano are both from Genoa) and Robinson Crusoes. This viewpoint, combined with Piano’s love for sailing and boat design, explains the approach and title of his book.

In the Logbook Piano speaks of the need for curiosity, tenacity, and experimentation during the design process as well as a willingness to try over and over again. He touches on questions of technique, the symbolic, emotion, and morality in architecture. He devotes sections to “contradiction and complexity” (in that order), “sustainable architecture,” and “regionalism and universalism.” Light, lightness, and transparency guide his work, and issues of ornament, nature, and style are considered. Concerning the city of the future, he expresses his hope that it will be like the city of the past, and Piano concludes with a short discussion on “a Humanistic Approach to Architecture.”

With The Complete Logbook I was especially curious and eager to see what new insights twenty additional and rich years of practice, experience, and, indeed, adventure had brought to Piano’s writings. I was disappointed to find that these guiding texts had simply been eliminated and only the logs of individual projects remain. Without the more general introduction and conclusion, The Complete Logbook lacks the generosity and the forthrightness of the earlier version. Some of the topics can still be found sprinkled throughout the various project descriptions, but they have lost their coherence and overarching pertinence. As the description on the back cover of The Complete Logbook suggests, the texts have drifted toward personal anecdotes. Piano is a skillful storyteller, and his project descriptions are always informative, interesting, and even entertaining. They are tales more akin to Mark Twain, however, than Palladio.

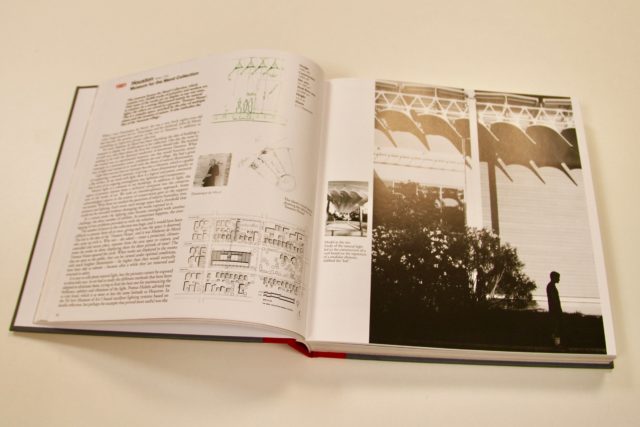

A short, opening text by the architectural historian and critic Kenneth Frampton has been tweaked and updated for The Complete Logbook. Its former title, “Placeform and Produktform,” has now been replaced by the very generic “Foreword.” Frampton’s ideas remain, however, and Piano borrows “placeform” from time to time in his own writing to reinforce the importance of context, genius loci, and topos in his work. Frampton’s explanation of his terms is especially interesting for a Houstonian audience since for him “…the Menil Collection… in Houston, Texas, seems to have played a decisive role in raising the level of [Piano’s] practice, largely because of the conscious differentiation between the topographic character of site and the mode of production. This implicit opposition between placeform and produktform ought, ideally, to be capable of resolution, and this is indeed what happens in the Menil Collection.”

I was a collaborator in Renzo Piano’s Building Workshop for 12 years in the 1980s and 90s, and I greatly admire the work the office produces. I am undoubtedly biased. Concerning the writing, though, while I appreciate Piano’s humility, it often seems exaggerated and gives a peculiar golly-shucks tone to his accounts. Modesty, however, is also woven with a portrayal of the architect as a hero, a champion, and a provacature. A decades-old, educational cartoon series for children popped to mind – The Big World of Little Adam. I imagine Piano sometimes in the role of the inquisitive Little Adam and sometimes in the role of his knowing older brother Wilbur.

Some of the problem in tone and language may come from the translation since the book was originally written in Italian. Piano’s exceptional work, I believe, generally speaks for itself, but within his anecdotes I can’t help wondering what he really meant when he called the Pompidou Center in Paris a “celibate machine” in the Logbook and corrected it with “bachelor machine” in the current version. Likewise, the explorer’s reports don’t always correspond with the international reach of his office and they sometimes seem to be for some imaginary, less-worldly public somewhere back home. While there are no claims of dragons and monsters at the end of the earth, Piano does sometimes make curious observations such as suggesting that Dallas is located in a desert, or that Los Angeles, “contrary to common belief, is a garden city filled with lush vegetation.” A gossipy sort might appreciate the tidbits related to personalities Piano has met over the years.

Also in the text on the Pompidou Center, Piano updated his mention of Philip Johnson (Johnson was on the Pompidou competition jury) as “…a prodigy, already an old man but still extremely lucid.” Even if that appreciation dates as late as the opening of the Pompidou Center in 1977, Johnson would still have been almost a decade younger than Piano is now!

Apparently, as log keeping goes, there is a notion of a “scrap log” that is a preliminary draft and the “official log” that is the final version. We can suppose that The Complete Logbook is now the official log. Piano has tweaked and revised the story of a career. At times he seems to struggle with past demons when he declares that for decades he was a sort of outcast and blackballed. In his book he explains and defends and sets the record straight for posterity. Still, I would recommend Piano’s simple Logbook from 1997 over his latest book. Its opening and closing texts are important, and they offer a more concise and accessible version of the profession of the architect and the builder.

Ronnie Self is Principal of Ronnie Self Architect in Houston. He was a designer and collaborator in the Paris office of Renzo Piano Building Workshop for twelve years. Self is Professor at the Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture & Design at the University of Houston.