Colley Hodges is an architect and former journalist. He currently serves on Kirksey Architecture's EcoServices team.

Immigrants to Houston once came by boat. They stepped off the muddy bayou banks. Buildings and bridges sprung from the soil like crops that follow a fertilizing flood. Most of the earliest buildings are gone, lost to flood and fire, to bigger ambitions and higher uses. Houston can seem like a city without a history, burying the past to climb higher on the horizon. But an effort to remake a landmark at the city’s birthplace marks a change in that pattern.

Since the early 1900s, the Sunset Coffee Building (then called the International Coffee Co. Building) has overlooked the city’s most historic site: the confluence of Buffalo and White Oak bayous north of downtown where, in 1836, the Allen family founded Houston and established its most important port for the next 75 years. After more than a decade of planning and two-and-a-half years of construction, the Coffee Building will soon offer Houstonians an unparalleled chance to reflect on our city’s history.

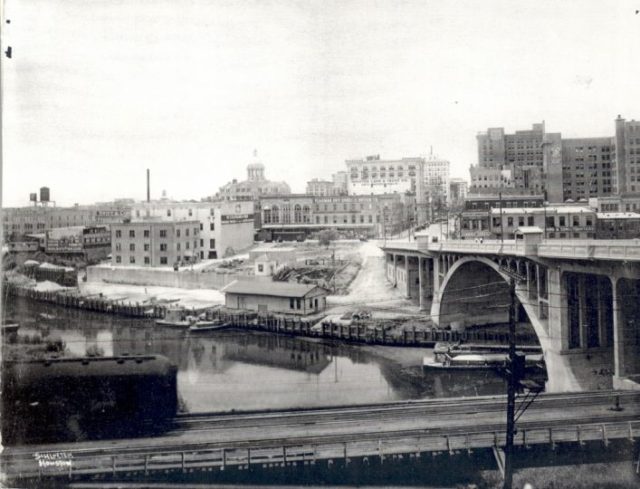

Allen's Landing in the early 1900s.

Allen's Landing in the early 1900s.

It is too soon to tell to what extent the Sunset Coffee Building will be embraced by the broader public. Called the most significant aspect of an extensive bayou revitalization plan, it is the result of a complex and necessarily heavy-handed renovation led, in part, by Lake|Flato, among Texas’ most celebrated architectural firms. But the renovated building is not remarkable as a singular work of architecture. Rather, its rebirth is significant because it is part of a major shift for the city. The renovation is a turning point. The building is the fulcrum for a monumental pivot in the patterns of this region’s development. From turning our backs to embracing the bayous. From purging to preserving complex histories. From car-dominated dispersal to multi-modal nodes. It is an invitation to think about the currents of our history, and a breakwater for future development. The building is positioned to be more than a pause on an extended bayou promenade. It could be a point of pilgrimage.

Seated atop a weathered concrete retaining wall at the water’s edge, the building was for decades a quiet partner in the city’s economic and cultural development. It appeared during Houston’s initial economic boom, participated in its mid-century countercultural movements, and became part of a struggle over how Houston will handle its historic buildings.

When Buffalo Bayou Partnership purchased the abandoned Coffee Building in 2003, consultants described it as the most significant part of the 20-year master plan for the bayou – “the lynchpin,” according to Buffalo Bayou Partnership President Anne Olson. Fearing that the building could be demolished by other owners and the character of Allen’s Landing altered by new development, the Partnership acquired the property in what’s been described as a defensive move and part of the organization’s long-term commitment to the most historically significant portion of the bayou. “We felt whoever bought it would probably tear it down and build a high rise. It being Houston’s most historic site, we felt we were saving the site as much as we were saving the building,” said Olson.

Impressed by the firm’s modern style inflected by Texas vernacular and its experience with adaptive reuse, the Partnership selected Lake|Flato, teamed with BNIM, as the architects. While other bayou projects were being completed, a decade of public and private fundraising developed along with multiple design iterations. After a half-million-dollar federal grant and close to $1 million from the downtown Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone, Houston First contributed the final major sum of money ($2.5 million) to move the project forward.

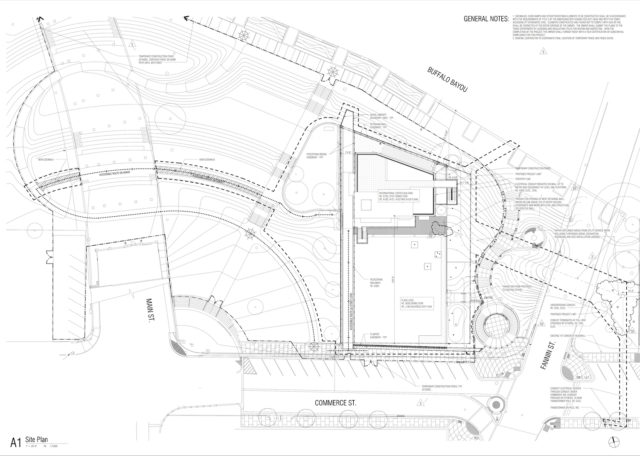

Houston First committed to buying the 12,700 square-foot building and operating a first-floor café and rooftop event space. Buffalo Bayou Partnership will enter a lease agreement to keep their offices on the upper floor. They will also facilitate kayak and bike rental at the plaza level. The Partnership offices have been housed in the building for roughly a year now, with the final purchase of the building and the café construction scheduled for the next 4-5 months. The office walls are lined with local artwork, and cubicles sit on the original slab over a Rorschach-patterned patina. Century-old concrete columns combine with newly introduced steel reinforcements.

Stocky and utilitarian, the building was first constructed in 1910 as a processing and distribution center for the adjacent W.D. Cleveland & Sons grocery supply and cotton trading building along Commerce Street. Sunset Coffee was a blend that they produced. The Cleveland building gone, now nothing stands between the building and Commerce except a wide empty plaza, eventually expected to be populated by patrons of the café. The profile of the bayou has changed through the years, and the surface of the soil is only a skin that has grown over what has been left behind. During the Coffee Building’s extensive renovation and site work, voids beneath the plaza caved under the weight of construction equipment, revealing remnants of the Cleveland building that had rested undisturbed for decades.

The Coffee Building had been abandoned for years when it was purchased by the Partnership. Vines clung to its exterior. Small sprigs reached out from windows. It was covered in graffiti and chipped, mossy green paint (an early design scheme kept the building green, but the idea was ultimately abandoned). In April 2006, responding to a federal immigration bill, tens of thousands of protestors marched to the site, invoking our shared history as a city of immigrants in what was possibly the largest rally in the city’s history, but most days it was a gathering place for the homeless.

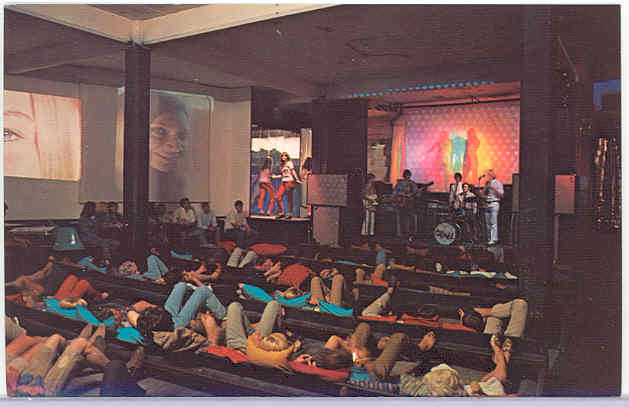

Inside the building were artifacts of its past lives. Psychedelic drawings lined several walls. An orange deer watching the viewer over its shoulder, leaping across the bricks. Toulouse-Lautrec styled cabaret dancers mid-kick, hair tousled and eyes closed sensually, rendered in powdery pinks and absinthe greens. The art appears to be a relic of the Love Street Light Circus Feel Good Machine, an experimental rock club owned by local sculptor David Adickes that occupied the top floor in the late 1960s. The building briefly served as the hub of Houston’s counter-culture music scene. Before that, it stood through decades of cultural changes across the city. The desegregation of lunch counters and downtown hotels amid orchestrated media blackouts. The waters flowed past its footings on a night in 1917, seven years after the building was constructed, when barely a mile up the bayou black soldiers and white policemen killed each other in the streets of Houston’s Fourth Ward.

Over the years as the city swelled, it rose around the site. Commerce was originally level with the Cleveland building. Without the Cleveland building alongside it, the Coffee Building is noticeably separate from the edge of downtown development, stair-stepped down from the street. The bayou and the street open the edges of the site to the sky. Fannin and N. Main cut across the waterway and provide a visage backdropped by Houston’s skyscrapers. For more than a century the building has seen the passage of people moving toward economic exchange, first down the bayou, now over bridges by the thousands.

The building’s most successful moments are at its boundaries in its interaction with public space. “It revolves around exterior spaces and connection to the outside,” said Joe Benjamin, an associate partner at Lake|Flato who served as project manager and design architect for the building. The prime pedestrian approach is from Commerce. A wide galvanized walkway passes over the pale crushed granite of the plaza and links to the sun-shaded southern façade. Due to the grants that funded the project, the team was required to follow guidelines from the Texas Historical Commission, including maintaining the existing openings on the north, east, and west facades. However, the Commission didn’t object to increased glass on the Southern street frontage that had been originally obscured by the Cleveland building. The transparency of the southern elevation offers a friendlier face to the street. The walkway extends past mature trees on the western part of the plaza – Buffalo Bayou Partnership’s windows look out into their canopies, a rare view for downtown office space. At first the walkway seems to drop off past the building or curl out of sight but it ends in an overlook jutted across the north lawn. It feels further extended than it is, like an outstretched arm that comes up just short. Looking up from the bayou below, the walkway reads like an industrial armature, a mechanism unfolding out from the building whose hinge is unseen.

During floods, the platform is suspended over rippled waters rising up the bank. The building and the plaza are designed to receive water during major rain events as well. Most days, the tides gently push against the slow freshwater flow from the two bayous until – perhaps once in a decade, more frequently in recent years – they rise furiously, flowing through the once blighted building, now staining its new burnished blocks. Perforated roll-up doors allow it to fill the lower level where kayaks and bikes will ultimately be stored. The plaza south of the building becomes a short inlet. Drains are integrated into the earth of the plaza. The elevator stops one floor short of the lowest level.

A new exterior stair touches down in the plaza and zigzags its way up alongside a multi-story corrugated steel cistern used for rainwater storage, a fingerprint on many Lake|Flato projects. The tank stands on a platform against the building, in front of several windows and accompanied by utility equipment that needed to be lifted out of the reach of floodwaters. It feeds a long red hose that will eventually be used to wash down kayaks and bicycles when they return from the bayou and its trails. A covered porch overlooks the water under an overhang on the north side of the building – an industrial alley of concrete, brick, and grey steel looking onto a short slope of grass leading to the bayou’s paved edge. Following the porch and crossing under the walkway leads to the west side of the plaza, which is hugged by galvanized guardrails and pleasantly shaded by oaks. It feels complete without any of the outdoor seating that may be introduced once the lower levels of the building are occupied.

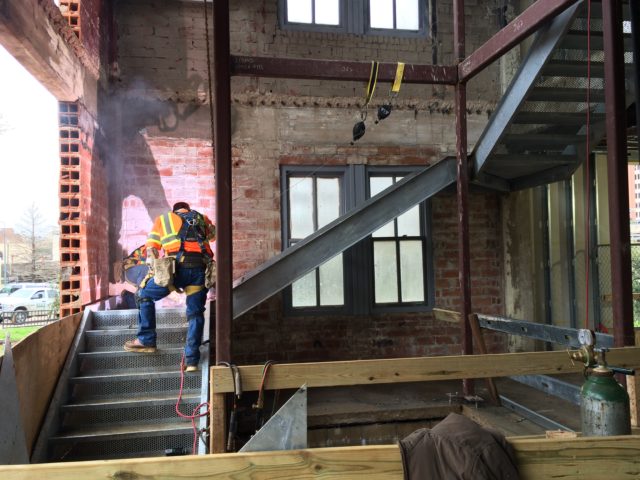

The Coffee Building is not a period restoration, nor a straightforward example of preservation and adaptive reuse. But it offers lessons for retaining a connection to history, original materials, program, and scale, despite numerous challenges. When construction began with Linbeck and Fretz Construction as the contractors, the project team intended to save as much of the existing Coffee Building as possible. Early hopes to salvage the exterior brick and structural clay tile dissipated when the mortar crumbled and critical damage was discovered. Portions of the clay tile were retained and left exposed on the building’s interior, and the new brick was carefully selected to match the old. The concrete structure had to be heavily reinforced and the ground floor slab re-poured. Some windows were salvaged, along with historic pavers that were dug up and relocated at the southern base of the building. Heavy metal bollards that once protected the original structure hug the corners of the building, rusted and buried in the concrete and brick.

“Every time they drilled down they hit something,” said Olson about the challenges the team had in dealing with poor soil conditions and the existing structure. Ian Rosenberg of INFILL, who served as project manager for Buffalo Bayou Partnership, said of the construction process: “Any challenge you can run into doing a 100-year-old building that had been vacant for 20-30 years on a challenging site, we experienced. We’re very proud of the outcome, but it was incredibly challenging.”

Through different owners and uses, the Coffee Building somehow survived the most troubled times for historic buildings in Houston. “The 1970s and 80s were the really dark times for preservation for the city,” said David Bush, acting executive director of Preservation Houston. “In the 70s, the north end of downtown was dense with historic buildings. Preservationists would be working to get them on the national registry, and owners would knock them down. Just the possibility of preservation would cause people in this town to demolish buildings.” If successful, the Coffee Building could reinforce a changing public perception about the value of historic buildings. It has opened just as other high-profile restorations are underway – the new American Institute of Architects headquarters, located a short walk down Commerce, and the controversial and long-awaited Astrodome renovation. Buildings are eligible for historical designation after 50 years, so an entire crop of structures from Houston’s mid-to-late century oil and gas booms are due. “Young people look at buildings very differently than generations before them,” said Bush. “They’re much more concerned with the historic fabric of the city. That is going to have an impact on the way we look at preservation in the future.”

A small glassed-in display room at the ground floor of the Coffee Building contains memorabilia acquired, in part, from Houstonians who have come forward during the project’s construction. A corroded Sunset Coffee canister. A small silver advertising token. A brick claimed to have been made from the clay banks of Buffalo Bayou.

The Coffee Building’s rooftop terrace inspires reflection on the patterns that have made the site significant. The constant passage of water carving out the banks, the rhythm of the tides pushing gently against the outward flow where the bayous meet the sea, the trickle of cyclists and runners on the trails, the intermittent freight train rumblings, the five- to ten-minute cycles of the METROrail. The skyline has its own visual rhythm. The massings of skyscrapers, the University of Houston Downtown campus, the hulking county jail with its dark, false windows. The terrace is likely to become one of the most sought-after small event spaces in downtown. It is bordered by the same galvanized steel guardrail as the west plaza, angled inwards above terra cotta coping. The terra cotta tiles are interspersed between newly installed and those the team was able to save – the color difference is noticeable and adds a touch of visual interest to the parapet. A portion of the roof is populated by native vegetation and intriguing large spherical lamps. Some are softly perched on top of the grass, like white balloons that lost their lift or bubbles waiting to pop. Others are nested in the grass like eggs. The terrace will overlook the trails leading from Buffalo Bayou Park, the connections coming from the Heights, and eventually paths extending east to Highway 59, passing under and through currently abandoned buildings along the bayou.

Significant efforts have been spent in the last decade on reviving downtown’s east end, including Discovery Green, which stands as a model for transformative public space in Houston. But the Sunset Coffee Building could spark a shift back to the bayou. Guy Hagstette, director of parks and civic projects for the Kinder Foundation, is a former Buffalo Bayou Partnership consultant with one of the most extensive resumes related to urban design in Houston, including serving as director of Discovery Green. He describes the Coffee Building as potentially as significant as Discovery Green, though for different reasons. “It establishes a beachhead,” Hagstette said of the Coffee Building. “People who haven’t been there before are always stuck with the magic of the location. I think it’s going to increase the profile of Buffalo Bayou in the eyes of Houstonians. Downtown needs more paces that offer a connection between the downtown experience and adjacent neighborhoods or natural features like the bayou. It’s going to be one of those places that Houstonians seek out reasons to go to.”

Looking out over the water from the terrace, it’s possible to imagine the flow of kayaks, rented miles to the west from the Dunlavy building at Lost Lake or arriving via White Oak from the Heights. It would be a return of the city’s first highway, leading to the foot of the Sunset Coffee Building, its red brick now accented by tectonic steel attachments. People will again step from the murky water onto the bayou banks, only now over pavement, but still heading toward the clattering of cash registers and the smell of coffee.

Firms

Contractors: Linbeck; Fretz Construction

Architects: Lake / Flato; BNIM

Landscape: SWA

Project Management: INFILL Planning and Development

Structural Engineer: IES

MEP Engineer: Henderson Engineers

Civil Engineer: United Engineers, Inc.

Lighting: Gandy Squared Lighting Design and Charter Sills

Elevator: Lerch Bates

Code: Rolf Jensen Associates, Inc.