If this topic interests you, buy the new issue of Cite, "The Beautiful Periphery." It includes a contribution by the interviewer in this article, the artist Carrie Schneider. The issue is available for purchase at Brazos Bookstore and River Oaks Bookstore, as well as the bookstores at the Menil Collection; The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Contemporary Arts Museum; and the Blaffer Art Museum. Read more from Cite 94.

Charles Renfro graduated from the Rice School of Architecture in 1989 and is among its most celebrated graduates. Rice recently announced that he will design a new opera theater for the school. In this interview, he speaks with Carrie Schneider about Open House, a one-day event in Levittown, a community outside New York City widely considered to be the archetype for post-war suburbs. Their conversation expanded from there to include the High Line, the Museum of Image and Sound, and the very idea of what constitutes a suburb.

Carrie Schneider: I recently found online images from April 2011 of Open House, the Diller Scofidio + Renfro project in Levittown that you were the project lead for, in collaboration with Droog. Can you tell me about it?

Domesticity Museum by Fake Industries Architectural Agonism subsidizes a threatened way of life with entrance fees.

Domesticity Museum by Fake Industries Architectural Agonism subsidizes a threatened way of life with entrance fees.

Charles Renfro: We thought of something that was central to New York City. Among other things, it provides an atmosphere and environment for self-making, making oneself, making one's own career—and the way that that is accomplished more often than not is through something that we call “the service industry.” We find that this is a particular attribute of New York City. You don't find this in other places, in European cities or in other less urbanized cities in the United States. We did a lot of research on the notion of service and how individuals without particular training or histories can remake themselves and give themselves careers in the most esoteric fields such as dog walking and couch remaking. We did surveys of all these businesses which were run out of people's homes or were homeless, that were lucrative and giving people lives of their own making in a kind of gray market environment. So that became the foundation of a larger research project into architecture, urbanism, and then later suburbanism. It started as an exploration about service and the overlap between residents in New York City inventing services and what that meant for architecture and the urban landscape.

CS: The language about Open House on Diller Scofidio + Renfro's website talks about the suburbs serving the city, and I had watched the New York Times video about your growing up in Baytown and visiting the architecture in Houston as a child. I was wondering what your thoughts are on the suburbs as a support structure for the city. In Baytown it's the petroleum and petrochemical services that are creating the big architecture in the city, and I was wondering if you thought of that relationship in the Open House project.

CR: Right. Well I think that the suburbs are the single biggest constructed problem of the 21st century because they are so dependent on fossil fuels and because they are typically dependent on metro areas or central cities. They are so unsustainable and also reprehensible in terms of their built environment. One of the problems with suburbs is that they are dependent on a central business district that is outside of their own rather than being thought of like small towns, which is, you know, how cities might have grown organically — they always have their own economic support structures and they weren't necessarily dependent on a central business district. So one of the goals with Open House was to help re-imagine suburbia both in its built form by changing policy, by changing zoning to allow for businesses to be introduced into residential areas, and to also change zoning to allow for densification of the residential areas. Our hope was to offer a model that would make suburban towns more economically self-sufficient and thus take them away from their dependency on the central business district in a metropolitan area.

Regarding my upbringing, you know, I think I epitomize, and my family epitomizes, the kind of post-war American dream. We were among the first true middle class. We participated in that expansion of homeownership. After the war, my parents bought their first home in the mid fifties, and you know everybody around us was in that aspirational category. No one realized that we were setting ourselves up for failure until much later.

At the time I was truly excited about what I saw around us. What I saw around me was growth and unlimited potential. But what has happened since the seventies when I was growing up, with these collapsed cites like Detroit, and to a lesser degree Pittsburgh, we've witnessed the loss of suburbia, and that's something that I think was shocking to a lot of people. Levittown, or other places once considered model suburbs like Sharpstown in Houston — these communities have imploded. Their unemployment is much higher than the central business district or the city that they surround, the life expectancy is less, the quality of life is less. So everything is turning out to be completely opposite of what we had imagined when we were growing up in these places.

CS: Doesn't that have to do with the aspiration now to move back into the city?

CR: Well, yes, but you have to understand why people want to move back into the city. It's a chicken or egg situation. People want to move back into the city because they realize the city is more exciting, more interesting, more sustainable, there's much more stimulation, all of these things.

CS: Right now it feels like everything interesting inside the Loop in Houston is being gutted and replaced, and the action is out in the suburbs. It's a bit of a reverse of what you're describing. All the diversity and the imagination is in the suburbs, almost as if Open House has already happened but without someone putting it in motion, because there's already no zoning in the strip malls and the suburbs within the City of Houston.

CR: So wait, what are you saying? It's the suburbs that are getting the interest in Houston?

CS: Right, it's where people go if they want the best food or the most interesting specific cultural experience or things that aren't master-planned development-led.

CR: Well that’s an interesting point and that of course does have to do with Houston's lack of zoning. Getting back to Sharpstown, I'm good friends with Mary Ellen Carrol who made her project, Project 180, and I helped her with that a little bit. When Sharpstown was collapsing and original owners fled, there was a lot of abandoned property. However, immigrant cultures have since moved in, and have taken up residence there and it's become a super diverse, very interesting location. Now I would counter your argument: what could be happening [in Houston], and what something like Open House tries to posit, is that suburbia can be made vital in its reurbanization. So in other words, not all hope is lost, because we can actually make the suburbs diverse business-wise if we change the codes and zoning. Since Houston doesn't really have zoning, it can become really interesting and perhaps denser. These places could actually be their own economic engines and their own self contained communities and not necessarily dependent on a central business district, so they're no longer suburbs. They're taking themselves out of suburbia.

When you say that it's the outlying communities that are more interesting in Houston, that could be true, from a diversity standpoint, but they may no longer be outlying. So for instance, if you're talking about the center of the Chinese community in Houston, it's in the Southwest side of Houston, but actually it's its own self-contained economic engine. It's one of many hubs that could be forming in that metropolitan area.

CS: I have a more abstract question: Is it possible to make democratic physical structures or gestures in the built environment even if the funding is from a capitalist structure and the operation is exploitative, and whether that formal or built structure can assert a change, or whether it excuses or veils the underlying system by creating a new facade?

CR: It's a really complicated question you're asking. It is something we ponder a lot up here in New York, in particular having gone through twelve years of the Bloomberg administration. Bloomberg personally and politically was a huge arts supporter and gave all kinds of money, through the city, through his own foundation, and from his own checkbook, to arts organizations large and small in a top-down way, which doesn't suggest democracy at all. It's not about people determining what should be done and how it's should be done, it’s a top down system. But it has really benefited everyone.

Just to use a project that we were involved in that had great support from the city, the High Line in New York. And I know there could be critique that it's in Manhattan in a privileged community already, and so it's sort of positioned as an elite and inaccessible project. But, it isn't. It's a public park, and more and more institutions of a public nature are gravitating this direction in the city. These have to do with museums, all running lots of foundations, art foundations and nonprofit arts foundations that are diverse and democratic, often not charging anything for entry. So the High Line has been a catalyst and armature upon which so much has happened, and it itself has been such a benevolent, magnanimous gesture to the city that I think it offers a kind of counter argument to the notion that top-down support for the arts is by definition kind of non-democratic.

I often say that, and this gets me into trouble sometimes, that one of the great things about the High Line is that the Friends of the High Line, the folks that ran the competition and subsequently became our client, trusted the design team and did not foreground our need to have design voices come in from everywhere else to kind of muddy the waters or kind of dilute the vision. Rather, they gave us the ability to exercise our design in its most robust fashion. Yes, it is not democratic in the least. You know, we met with community groups. We heard their resignations, and we took them into consideration, but in a way that filtered them through the larger ambition of the project.

I'm just trying to illustrate the trickiness of the notion of cultural projects being democratic, how difficult it is to take them in a black or white situation, particularly in 21st century America where most of our funding comes from private individuals and corporations. The only way to change that would be essentially to get back into more socialist lines of thinking and more people will support government funding for these kinds of cultural organizations.

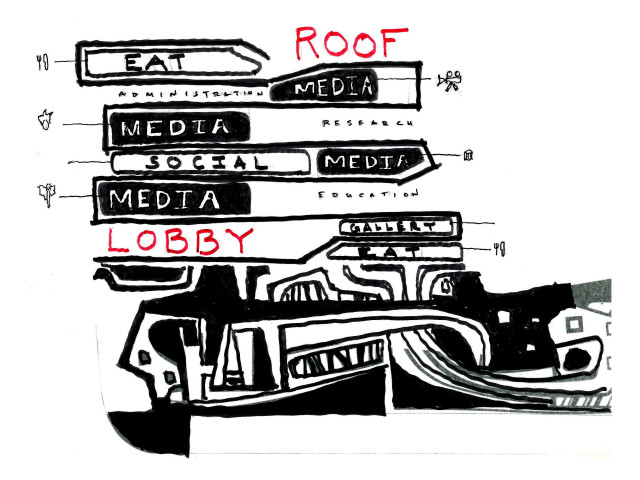

It is a wonderful time to think about the notion of democracy. Our other projects try to give back to the public more than the owner imagined would be possible in the first place. Our Museum of Image and Sound in Rio de Janiero, which is a museum that is dedicated to the city of Rio — her artists, and art, and art made about Rio de Janiero. Our design proposal made it possible for non-ticketed patrons to come straight off the beach where it's located, on Copacabana Beach, and ascend the building into gallery and museum spaces, and then finally end up on a public park and screening room that's on the top of the building. And this wasn't in the brief. It was something we brought to the table. We often call the beach a place of democracy in Rio, it's a place where everyone, the haves and the have nots, end up. Our project wanted to be an extension of that democratic surface where everyone is welcome and where everyone feels comfortable. So that's just illustrating a notion about democracy and I use the term very, very broadly — that we can make work that is very welcoming and egalitarian without having its funding sources be from the bottom up.

CS: And then on the resulting side, it sounds like there's a belief that you can build a new thing and keep it from being instrumentalized in the same cycle it was invented to oppose, which is optimistic.

CR: Right, I mean, you know these are all interesting questions.

CS: Well I was struck by one of your talks when you were showing the High Line before anything was done to it, and it seems like there's a tension between what you just described in allowing access — or the visibility of the Julliard school looking out — versus creating access and visibility of precious or un-found spaces undermine what it is that is special about the space? I wonder if there are any projects you've done or thought of that are intended for no audience, or meant to —

CR: Keep something private.

CS: Yeah, or as is. Or the act being the act of not acting.

CR: Right. Or, is this sort of a question about preservation?

CS: It is a little bit in the sense that it feels like once things get discovered, and have the touch of someone who is a cultural catalyst — somehow they're representive quality or the cultural cache of them gets preserved and funneled up the food chain, but the actual thing sort of loses. So I hear you speaking about visibility and the access of a direct entry from a public area to an institution, but I wonder — what about the reverse? Taking inspiration from public things and then lending them to private, or more elite, uses?

CR: Right, if it's a reverse flow. If a reverse flow is possible...

CS: And in a way that's not just — I don't know, you should just speak because I'm not even sure what I'm asking.

CR: Well, I mean, it's interesting. I think one of the things you're lamenting is a kind of loss of character. You know, there's sort of discovery, and we've been behind several projects where we're trying to "part the curtain" let's just say. And as we're parting the curtain we're actually taking the thing that made it interesting to part the curtain in the first place and making it no longer be that thing.

So, by acting on it we're actually transforming it to the point where it no longer deserves that action. And it's an interesting rhetorical question, and you know, a question of when to say no, I guess. With the High Line, would it have been better just to leave it as a ruin? Because it was quite beautiful, and the few people that were able to go up there did so illegally. Would it be an eyesore? Or would it be great to think of how there's this inaccessible thing and that makes New York so exciting and weird and interesting? You know, now it's been such a huge boon to the city that I think we have to say that it was the right thing to do [to transform it into a public space].

There were four finalists in the design competition that offered a set of approaches that couldn't be more different. So Steven Holl’s approach brought a ton of retail up there to the highline level, to turn it into another street, a retail street. Zaha Hadid wanted to turn it into a platform that would eventually become a sculpture. And then the other landscape team, Michal Van Valkenburgh, had a very sensitive scheme, and a design not that dissimilar from ours, that had surgical interventions but actually tried to keep the essence of the line as a kind of ruin. And then ours again which tried to update it and make it open to the public while taking all of its material and design clues from what was there before, because it was a ruin and how do you immortalize a ruin, you know? Or is that even what we were trying to do? I think we were trying to walk the line between straight design and a found thing that we just opened to the public.

We are sensitive to the notion of popularity, whether or not that's a blessing or a curse. The High Line is again a great example of that, having been designed for 300,000 visitors per year and now getting between two and three million. It's own success has made it a different kind of experience than it was imagined. It was imagined to be a much more contemplative, solitary experience with benches on it.

CS: For Open House, people were bussed in to look at the installation. Would it be preferable that it does not remain a spectator thing but a participant experience?

CR: Yes. We made that project, Open House, a spectacle, in order to highlight the potential of what a non-spectacular transformation could do. The essence of the project was to say that these people who live there, who were all out of work, all have these talents, like counseling — come seek the advice of an old lady $5 a session. It needed to have an architectural spectacularness. The project was given an overlay in order to draw attention to itself. The take away is that there's a lot of potential to remake these suburbs and make them healthier communities. And there could be an architectural implication and densification, because we all know that denser living is more sustainable and more healthy. That was one of the biggest mistakes we made was to make these hyper-spread-out communities, and trying to counter that is one of the most important things we could do. But it wouldn't have to be in this kind of spectacular installation quality that we did for that one day out in Levittown.

CS: The idea is that it would be its own self contained market — its most ideal form.

CR: Yes, inevitably there is going to be some dependence on New York City, but it could be a much healthier living and working experience rather than a singular monoculture. That's what we're talking about — making the suburbs a multiculture, not a monoculture. Changing the nature of the beast.