It’s a strange time to view art. Still, Rewrite the World, installed at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston (MFAH)’s Glassell School of Art, makes prolific use of the latent energy of our strange times. It assembles a politically charged, radically imaginative collection of artworks. Curated by Ana Tuazon, a 2020-1 Critic-in-Residence at the MFAH Core Program, the show challenges attendees to think critically and creatively beyond the walls of the gallery space—wherever we may find ourselves and into whichever worlds we’ve been written.

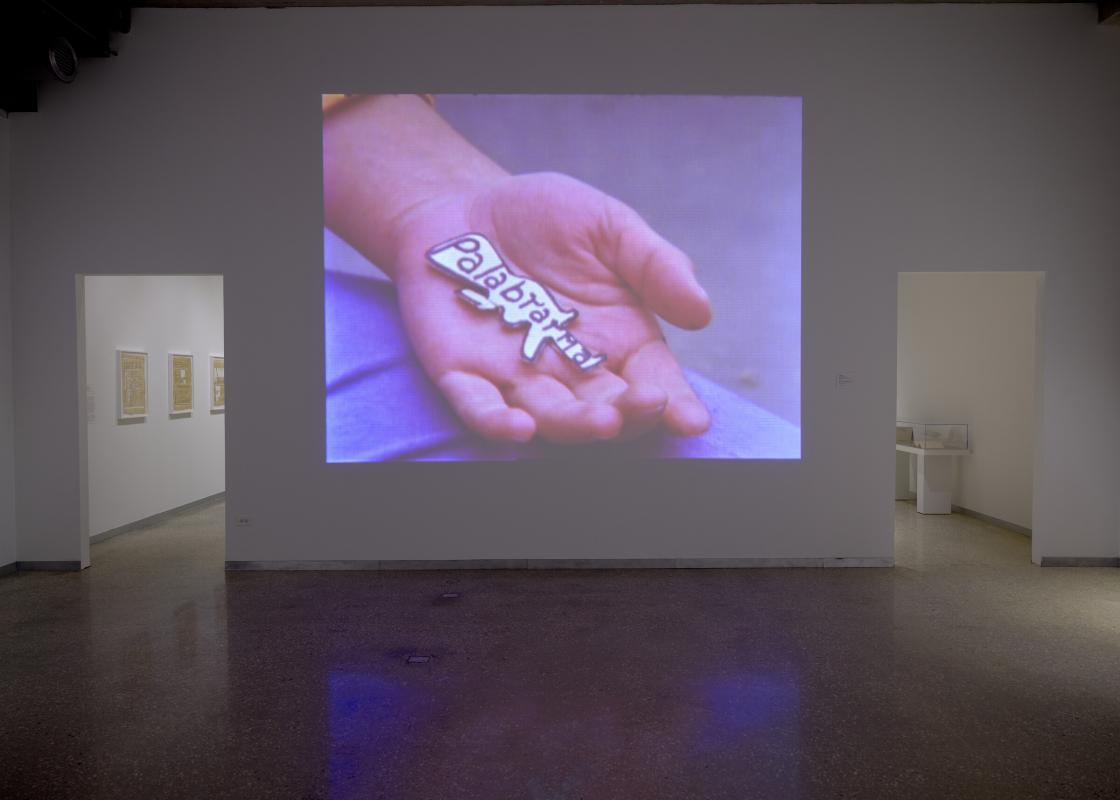

Composed of works from four artists, the show has multiple gravitational centers distributed across its two rooms. Across from the entrance, two of Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña’s video works are projected at monumental scale. Vicuña, whose career has been distinguished by resolute anti-fascist politics and restless mastery of different techniques of artmaking, approaches her projects with both a playful spirit and urgent seriousness. Palabrarmas (1980) meditates colorfully upon a portmanteau—the joining of palabra (word) and armas (arms)—even as it is haunted by the context of Vicuna’s exile in New York: She fled in anticipation of the right-wing (CIA-backed) Pinochet regime and its silencing of critics. The second film, Sol y Dar y Dad, una Palabra Bailada (Solidarity, a danced word), also from 1980 and also revolving around wordplay, adopts a more utopian tone. It documents a group of performers playing in a park, a balloon inscribed sol (sun) bouncing between them; eventually nearby schoolchildren join, further enlivening what is perhaps only accidentally an homage to Matisse’s famous Dance.

Several contributions from Newton and Helen Mayer Harrison, artistic and romantic partners, provide a melancholic contrast to Vicuña’s radical optimism. The Harrisons were early adopters of the effort to raise public awareness about global warming and environmental devastation. Together they have interwoven threads of literary invention and scientific communication. On display is The Book of Lagoons, a massive art-book that is part of a larger project, is an absorbing speculative elegy that resists despair.

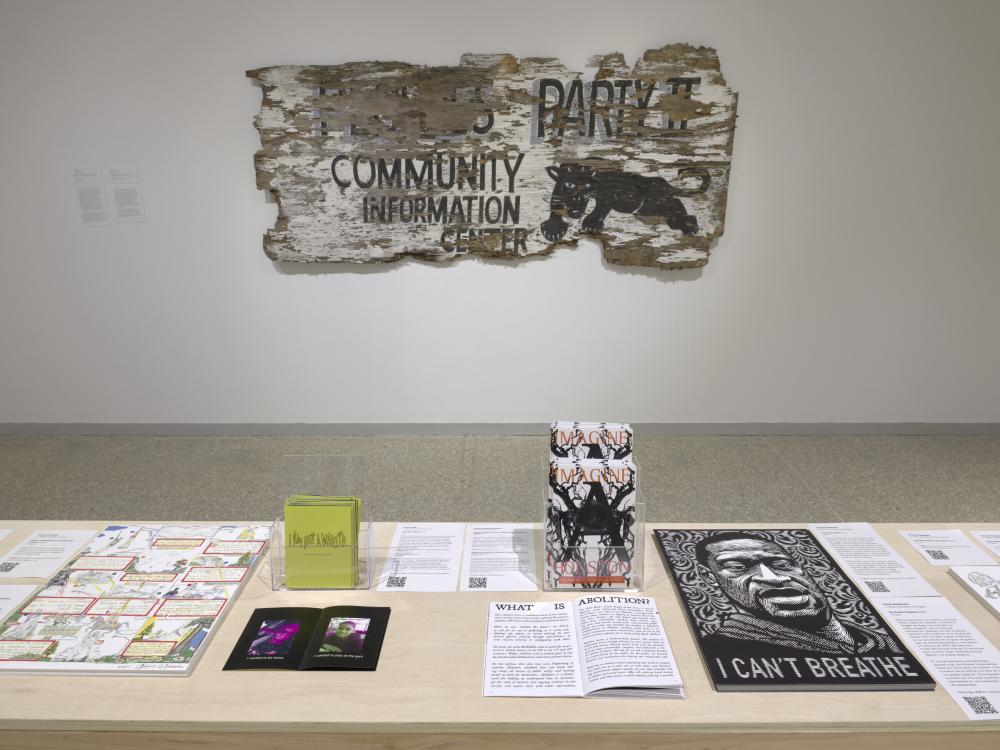

In an adjoining room, the work becomes more confrontational. Houston artist Jamal Cyrus (whose work is also currently on display at the Collect it for the Culture exhibition downtown), is, like the Harrisons, concerned with raising awareness: His work mourns the murder of revolutionary Black activist Carl Hampton by the Houston police in 1970. Eroding Witness 7 contemplates the ideological inflections of different press reactions to the killing at the time. These front pages are laser-etched on papyrus. On an adjacent wall, Replica of a Lost Original (After 2007) is a visually powerful recreation of the sign Hampton hung on the headquarters of his Peoples Party II in the Third Ward; the black panther crouching on its artificially weathered surface vibrates with revolutionary intensity.

In a thoughtful and effective departure from gallery convention, the second room presents a collection of print materials by local and national artists and activists, which attendees are invited to take home. These posters, pamphlets, and zines create a rare opportunity for the exhibit to physically cross the threshold of the gallery walls, disrupting the effect of containment and neutralization that often characterizes the typical interaction between museum-goer and museum. Included are copies of Imagine a Houston that Keeps George Floyd at Home, Alive, & Safe, a zine by the Houston Abolitionist Collective, which is devoted to the urgent political case for dismantling the racist institutions of policing and the carceral system, and I Am Not a Martyr by Alyssa Cuffie, created “in honor of Ahmaud Arbery and the thousands of named and unnamed black people who have suffered at the hands of white supremacy and the lack of consideration for their humanity.”

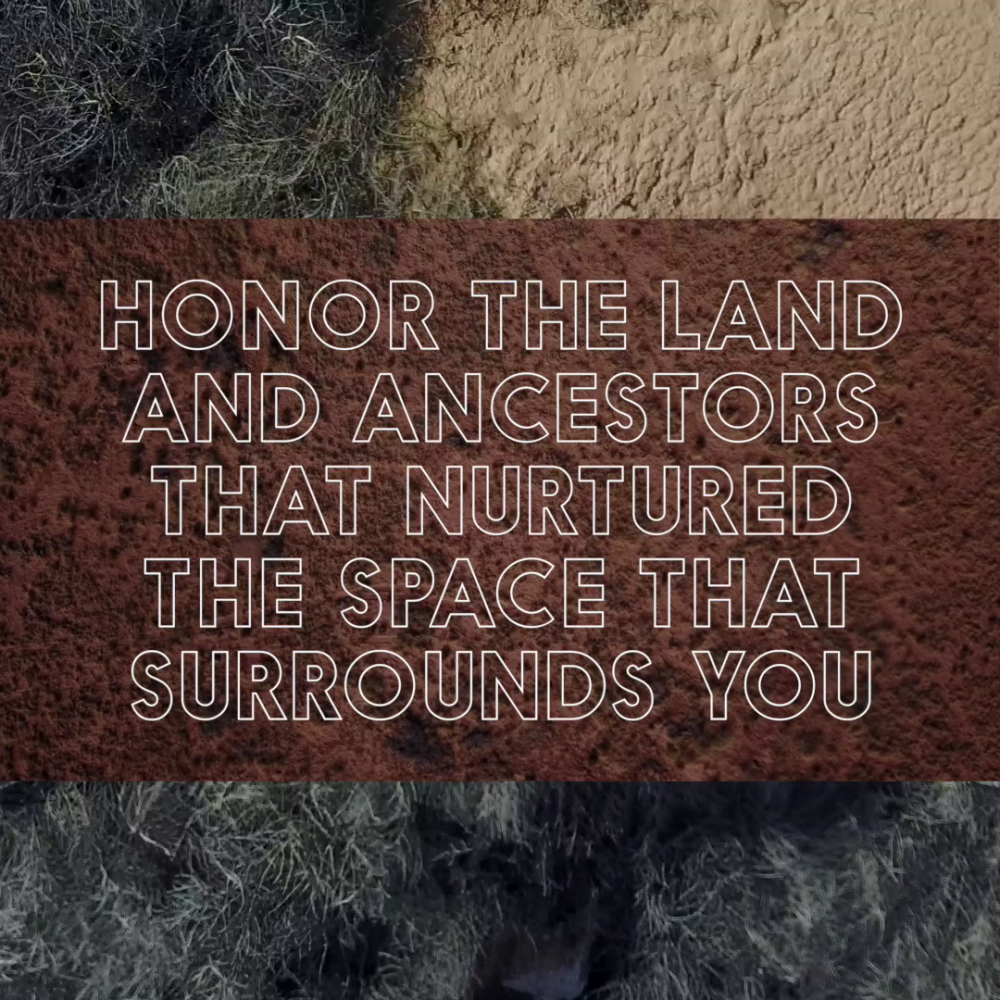

Rewrite the World’s final component is a pair of works by Native American artist Demian DinéYazhi’. The video piece Burying White Supremacy (created with Ginger Dunhill) loops on a TV and offers instructions for conducting a ritual to bury the white supremacy that “cowers” within oneself. Luminous capital letters imposed over panning shots of desert landscape encourage viewers to “Remember all the robbed graves whose contents reside illegally inside museums.” Viewers may feel productively self-conscious—if, for example, they recall the sizable collection of “Pre-Columbian” art on display at the MFAH.

Another contribution from DinéYazhi’ is We Don’t Want a President, 2018, a blistering, decolonial-anarchist revision of Zoe Leonard’s often-reproduced I Want a Dyke for President. DinéYazhi’’s works complement each other; they operate as a microcosm of the entire exhibit, which oscillates between radical rejection of the world as it is and the imagining of those more just worlds into which it might transform. I understood the artists as all, in their own ways, practicing what Sylvia Wynter has termed “counter-cosmogony,” which gestures toward the calling into being of a different narrative of the cosmos—one intentionally committed to radical justice. Anti-fascism, ecological awareness, decolonization, abolition, and respect for Black life: These are the prefigurative commitments that animate Rewrite the World.

Tuazon has assembled an abundance of revolutionary imaginations here. They teem within the gallery space, prepared to advance beyond walls of the Glassell and into that world we call “the street.” These walls are the white surfaces associated with “the gallery”—they constitute the frame that frames the frames. Brian O’Doherty introduced the critique of the “white cube” in 1976, identifying its subtextual significations of purity, sanity, and secularism, though missing its now-obvious racialized and colonialist dimensions.

Rewrite the World exists in stark contrast to its location within the conventional space of the white cube, which represents precisely the kind of structure it is committed to dismantling. The show may hopefully provoke visitors to question the way in which the “world” of white Cartesian gallery space reproduces itself and the chain of significations upon which it depends. Thankfully, the new Glassell in its broader entirety deviates somewhat from the habits of “good art-institutional design”—it lets in natural light and, atop its sloping roof, offers some desperately needed public space where, one day soon, we may gather again.

Rewrite the World is free and open to the public through February 28, 2021. True to its project, it includes bilingual placards. Additionally, the show exists in a richly interactive virtual iteration.

Sam Stoeltje is a PhD candidate in the Department of English Literature at Rice University. They have written for Hypocrite Reader, La Voz de Esperanza, and Speculative Arts Research, and they blog at www.paracultures.com. They sing, they dance, they are from San Antonio, and they believe in ghosts.