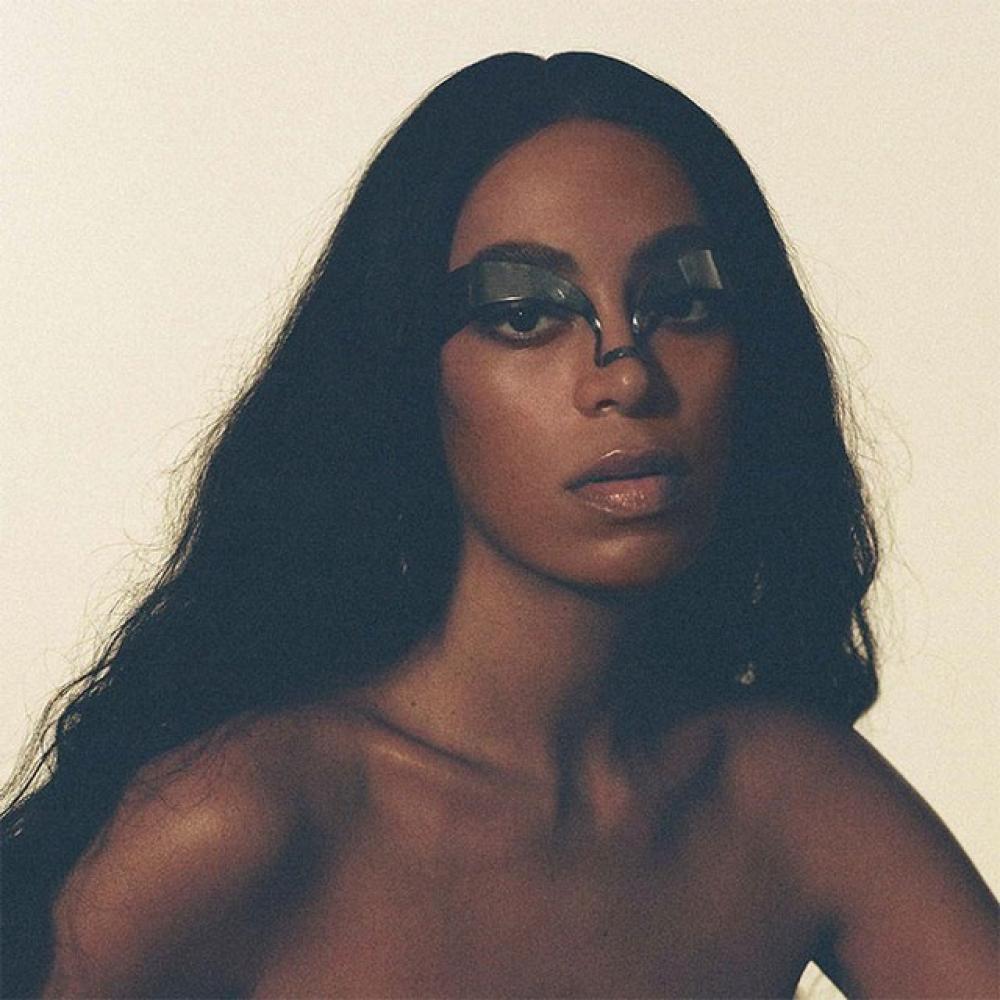

Perhaps no performance artist in recent history has paid such exquisite tribute to her hometown as Solange with her 2019 film and album When I Get Home. When viewed through the lens of these terrifying yet pregnant times, it becomes even clearer that the work is daring us—Solange is daring us—to reckon with and celebrate the past and the future. Houston, with its multitude of American microcosms, is where Solange Knowles was born in 1986, the year of the first FotoFest Biennial. The city stands in for so much in contemporary culture, and especially for Black America, whose fate is intertwined with that of everyone’s on this planet.

The Third Ward, an important area for Black history and contemporary Black culture in Houston, is where Solange staged multiple screenings of When I Get Home upon its premiere last year. Locations included Texan Tire and Wheel, the Black-owned Unity National Bank, the Ensemble Theatre, where she stared in The Wiz as a young person; Emancipation Park, without which Juneteenth would be nothing but a vague notion; and Vita Mutari, the hair salon her and her sister Beyoncé’s mother Tina Knowles-Lawson used to own, a kind of ground zero for Black society in Houston. The film also premiered on Solange’s Black Planet page, a sly nod to recent history (Black Twitter before Black Twitter) and one that forecasted our current pandemic-era “virtual” cultural paradigm.

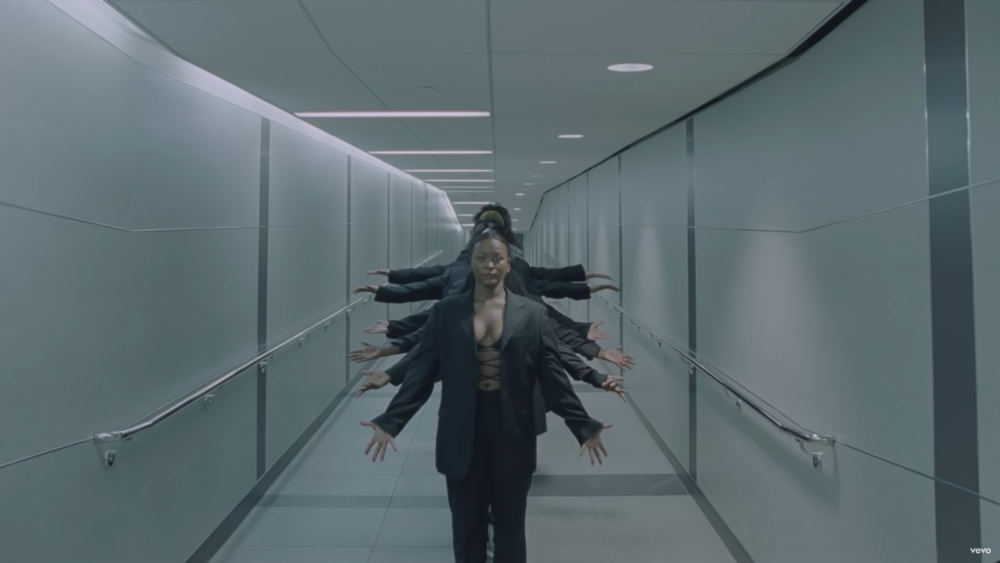

When I Get Home springs from the Houston of Solange’s third eye, deeply connected, specific, rooted, enigmatic, and experiential. It reflects the varied cosmopolitan experiences she had growing up and her current protective, nurturing embrace of Houston and her home state. A heartbreakingly beautiful film collage, it takes the best attributes of remix culture and applies them to Houston’s architecture styles, from row houses to colonial revival mansions to postmodern ‘80s downtown skyscrapers to the Renzo Piano-designed Menil Collection, which she grew up visiting and where she recently performed. The film is first and foremost an ode to Blackness and Black collectivity, and expressly Black female collectivity, within a uniquely African American experience.

A standout track on When I Get Home is “Almeda,” named for the street in the Third Ward, where Solange is from. Co-produced by Pharrell Williams and featuring Playboi Carti and The-Dream, the track channels 21st century negritude and evokes the chopped and screwed genre, a Houston-based remixing DJ style immortalized by DJ Screw, the patron saint of Hip Hop Houston who died tragically twenty years ago. Solange sings:

These are Black-owned things

Black faith still can’t be washed away

Not even in that Florida water

Not even in that Florida water

In that Florida water

Elsewhere, Solange chops and screws her own voice on When I Get Home, like a modern-day version of scatting—listen for it. The album builds off her previous and third album A Seat at the Table, which was inspired by the poet Claudia Rankine’s opus Citizen. That release leans Apollonian in comparison to When I Get Home’s Dionysian slant. The music video for “Cranes in the Sky” from A Seat at the Table was shot by Director of Photography Arthur Jafa, who is one of our era’s most prominent chroniclers of Black America in films like Dreams are Colder Than Death and Love is the Message, The Message is Death. Solange’s video features locations throughout Texas and foreshadows When I Get Home with its scenes on the stairs and in the lobby of Houston’s Alley Theater.

This work of interlocking dream logics defies easy categorization; it isn’t hampered by zoning laws of the mind. At work in its imagery we see the aesthetics of Afro-Futurism and Sun Ra, the Black Cowboy, the Yee-Haw Agenda, Black Power, the Black Arts Movement, unisex Florida Water cologne, artist Betye Saar, the AfriCOBRA collective, Afro-Centricity, sex positivity, VR-style digital animation, experimental film and music videos, the Space Race and NASA, Busby Berkeley musicals, large scale art and architecture, theatre, dance, and the natural landscape. When I Get Home is an thoroughly postmodern work, reflecting the postmodernity of its origin and inspiration: Houston, America’s most diverse, sprawling, and slyly futurist city.

I came to Houston for the first time a year and a half ago when I began a new adventure as Artistic Director of the Houston Cinema Arts Society, right around the time When I Get Home was released. The album quickly became my muse and guiding light, and a celebration of my own Black American womanhood. Because of COVID-19, I haven’t been able to return to Houston, which I have fallen in love with, and so I stay and wait in New York City—my first love, where I was born and raised—and work from with folks in H-Town remotely.

In the meantime I dream of Houston, inspired by Solange’s Space City fever dream and its cavalcade of stars, both those in the film, like the incandescent performance artist Autumn Knight and Houstonians Phylicia Rashād and Debbie Allen, and those in its orbit, like George Floyd (1973-2020), his family, and the Third Ward where he grew up; the polymath opera singer and filmmaker Lisa E. Harris, who also resides in the Third Ward; DJ, filmmaker and historian Flash Gordon Parks; rap legend and pioneer Bun B, the band Khruangbin, the rapper Tobe Nwigwe, reppin’ hard for Houston Nigerian community, rap juggernaut Megan Thee Stallion, and multimedia artist, DJ, and curator Stephanie Saint Sanchez; dancers Harrison Guy, who founded Urban Souls Dance Co., and Lauren Anderson, who Solange went to see dance in the Houston Ballet as a child; writers Jia Tolentino and Bryan Washington; and filmmakers Justin Simien, Trey Shults, and Bassam Tariq.

In When I Get Home, Solange gave me a road map that I continue to refer to as I endeavor to love and understand Houston, a place that takes me around the corner and around the world.

Watch the Director’s Cut of Solange’s When I Get Home film here.

Jessica Green is the Artistic Director of the Houston Cinema Arts Society. She is also curating a film and speaker series for the Museum of the Moving Image titled "The Afro Future's So Bright I'm Pessimistic" and developing a narrative television project about Louis Armstrong’s State Department tours. She was the Cinema Director of the Maysles Documentary Center in Harlem, founded by legendary filmmaker Albert Maysles, from 2008-2018. Jessica is also a former founder, owner and Editor-In-Chief of the New York based, independent Hip-Hop magazine Stress (1994-2001), which was the first magazine to put Jay-Z on the cover, as well as the former Executive Editor of BET.com (2000-2005). Green has an undergraduate degree from Lang College at the New School for Social Research in Black Studies and Writing and Literature. She was born and raised in New York City, and her father Ernest Green, is one of the Little Rock 9.