During the pandemic, our work and personal lives have been flattened to the screen, as most everything takes place virtually. Art that’s outdoors and publicly accessible gives us a much-needed break from the screen. Color Field, on view through May 2021, is a new opportunity for Houstonians to view art in a socially distant way on the University of Houston campus. Color Field is a walkable collection of sculptures sited around the campus, each with their own attention to color. Site-based three-dimensional artwork demands that we experience it with our whole bodies, and Color Field is best explored slowly in real life. A placard describing the work of artist Sara Braman stated that “slowing down to encounter shifting light and color can be a transformative experience.” As a temporary exhibition, the works are delightfully sited within the campus so that each piece can be taken in with its context and we can confront the large-scale colorful forms with all of our senses.

Color Field lends itself to a slow and steady walk-through. It’s like an outdoor sculpture park without the crowds, since the campus is relatively quiet during the pandemic. A good chunk of the City of Houston’s public art collection exists at the scale of the freeway, meant to be experienced as we whiz by on our way somewhere else. We perceive our freeway art at a glance—just for a moment—without the opportunity for introspection or up-close observation. Color Field is an opportunity to take the time to watch how the change in light affects each piece and to discover nuances of the campus along the way. Each piece is spaced along a route marked with wayfinding flags and with enough distance between them so that you can encounter the works as individual art pieces that are integrated into their context. Spencer Finch’s Back to Kansas features a big grid of colored squares that change to grey as the sun lowers. The work’s large scale puts it in conversation with the nearby buildings, as its the extra-large canvas is stretched over a metal frame and floats a few feet off the wall.

The works throughout the show are vibrant pops of color against the earthy monotone of concrete and exposed aggregate of the UH campus. Color is light made visible to us at different wavelengths, so a sculpture show about color is intrinsically about light as well. Color is a shapeshifting material in how we see it over time, especially under the degrading effects of sunlight. Only the toughest enamels, industrial resins, and gypsum compatible dyes stand up to the sun’s brutal UV rays. In that sense, specific colors are a temporary material. They have to be re-painted, re-coated, re-finished, sanded again, over and over to maintain a semblance of consistency over time. Everything fades in the sun eventually, which makes it appropriate that these artworks are installed temporarily in this public format.

The work in the show is oriented along a looped route that mingles well with the permanent public art collection at UH. Typoe’s Forms from Life is a series of whimsical bold forms sited like chess pieces on an elevated grassy plinth. At the tip of the circuitous route, you step onto the plinth to discover Typoe’s vision right as you are then drawn into Lee Kelly’s permanent stainless steel sculpture, titled Waterfall Stele and River. At another point, Carlos Cruz-Diez’s Double Physichromie feels like a natural pitstop in the Color Field exhibit; its masterful manipulation of precise color shifts our very perception of it. To achieve this effect, Cruz-Diez practiced a devotion to precise color application, and it is this precision that creates such a delicate and profound shift in color in relation to the movement of our bodies.

The artworks all engage with color, but one outlier is the supersized functional windchime by Sam Falls, which is notable for its intentional and aggressive breakdown of color. As the hollow metal tubes clang against each other, the powdercoated color chipped away upon impact, by design. The color is a temporary material, but one that is expertly integrated into the life of the piece: The sculpture contains a record of its own movement in the wind as the paint chips away. The piece is a great example of semi-permanent, or transient artworks, which take advantage of their temporary status.

In the spectrum of permanence in outdoor artwork, one end are works like Andy Goldworthy’s leaf circles that can be blown away by the wind, while the opposite end has the most enduring and often monumental works of steel bound to the earth with concrete foundations. The squishy middle of the permanence spectrum is where it gets interesting. If the work isn’t meant to last for decades with periodic restorations, then what new actions open up within the work itself? Furthermore, what do we gain and what do we lose in the drive towards static permanence in public art?

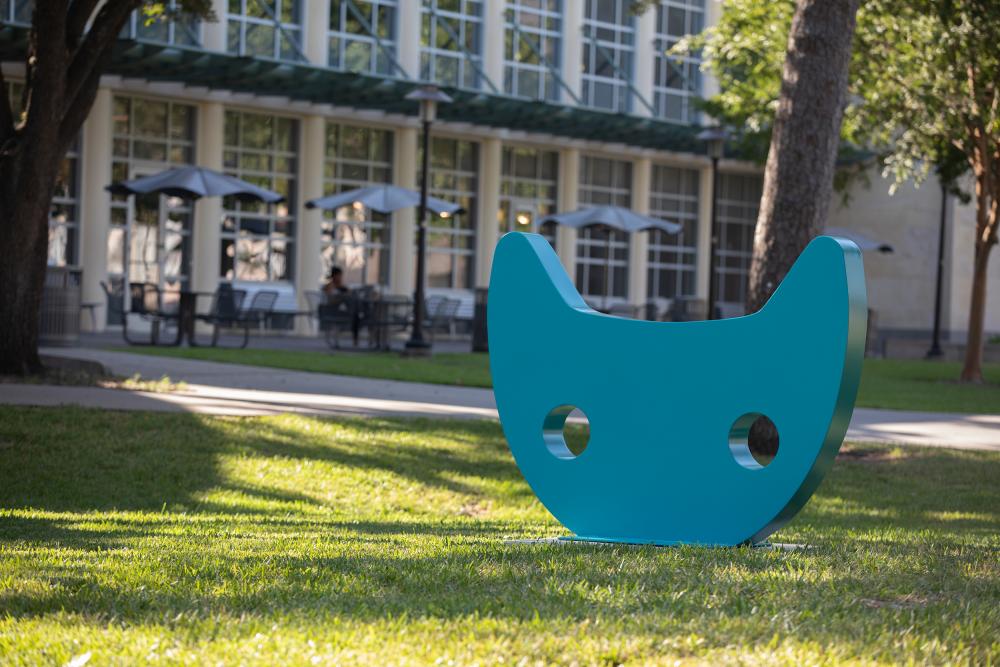

Some of the pieces are materially static, such as the painted aluminum works by Jeffie Brewer. These bring a whimsy and sense of humor to their form; they appear as if they are in motion, like characters in a video game, with names like Cloud, Kitty, and Bunny. Other works have shifting effects that play out over a more subtle timeframe. The light seen at different angles in Here by Sara Braman is a prime example. The concrete drainpipe punctuated by colored plexiglass acts like an abstract sundial. On repeat viewings, you could track the movement of colored cast shadows relative to the time of day. Another piece with time embedded into color is in the layering of shadows and light in the composition of light-reactive enamel in Untitled (Maze) by Sam Falls. The work will look very different at points throughout the nine-month exhibition. There are cognitive benefits to artwork that requires a curiosity and thoughtfulness in the viewer, making Color Field a nice addition to a college campus where the work can be encountered by an engaged public. As he walked through the exhibition, Zabdiel Rodriguez, a UH undergraduate student studying music, said “it gets the gears turning even without any conclusions about the work. It’s making me think as I’m looking at it and taking it in.”

The current expectation for contemporary public art is that it should be interactive—or at least “Instagrammable”—to grab the attention of a distracted public. However, with its singular thread and consistent focus in the experience of color, Color Field feels slower and more studied. It is a return to public art that treats the audience as a perceiving, thinking spectator, and not an active participant. [1] The works in Color Field show us that color has a tricky and mesmerizing material quality that is ever-changing when illuminated by the sun. To see this, we have to step away from the screen to experience the work firsthand; we have to take the time to slow down and look.

Falon Mihalic is a landscape architect, interdisciplinary artist, and founder of Falon Land Studio. She is Co-Chair of RDA’s Publications Committee.

Notes

[1] For more about the shift in public art towards interactivity, see Miwon Kwon’s One Place after Another: Site Specific Art and Locational Identity, published by MIT Press in 2002.